THE BONZO, GNATSNAPPER, ACCOUNTANT AND THE JOYS OF 1000 AIRCRAFTPHOTOS.COM

The internet changed everything. It certainly changed me.

I have been writing stories about aviation history for about nine years now. It is not something I thought I would ever do, but by my estimation I am beyond 2.5 million words at the time of this writing. While quantity is certainly not a great metric of creative historical writing, it is indeed a measure of the joy that I have found in my research, writing and publishing. The singular most important driver of this output is the rich textual and visual record found on the internet.

Each time an idea comes to me for a story, it is delivered from out of the blue World Wide Web—either from an email that inspires, an image that captivates or a series of images that begin to tell a story. Then I set to work to find out as much as I can about the subject, be it about aircraft manufacturing plants in the Second World War, landlocked aircraft carriers in the Great Lakes or the ubiquitous squadron dog. The beginning of any story is an exciting digital quest for images, anecdotes and information that continues to teach and thrill up until the moment I click the button in my Content Management System that says “Publish”.

Not long ago, researching the crash of a single Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Handley Page Halifax bomber in a small town in France during the Second World War would be so complex and so far beyond most people’s reach, that it was not something ordinary people like me did. Researching such a simple subject required travel to London, England to visit the RAF archives for copies of the squadron’s Operations Record Books (ORBs); trips to the National Archives in Ottawa to ask for and review the service records of the Canadian members of the crew (and then only if they had died) and possibly a number of trips to France to find and interview witnesses, photograph crash sites, review church records and pay respects at memorials, or even to Germany’s Bundesarchiv to sift through Luftwaffe records or to find and interview still living fighter pilots. The process would be so daunting as to be only for the true historian—men like Canada’s Hugh Halliday, a respected historian who has been researching and writing both broad interest and esoteric historical books and magazine pieces for many decades before I even started playing in the same sandbox.

The true historian was willing to sacrifice many hundreds of hours and plenty of resources to achieve his or her goal, and was willing to allow months and even years to pass before gathering the information, accounts and photographs required to write the compelling story of one crash out of a hundred thousand such crashes that occurred in Europe during the Second World War.

That has all changed. Completely. Now, I can pay and download digitized and relevant squadron ORBs direct from the British National Archive, view digitized service records and find amateur websites that collect, record, analyze, sort and display information on all the Allied and Axis crashes that happened in France—by aircraft type, date, place or country. I can find the names and often the email addresses for still living men and women who witnessed the crash or perhaps their children. I can find accident reports, obituaries, newspaper clippings, period magazine articles, gazetted decorations and promotions, book references, aircraft production lists, aircraft movement cards, telegrams, war graves and often images of the very aircraft or persons I am looking for. I can use Google Earth to visit the graves, tour the towns and villages and in some cases still see the still-extant scars of craters of bombs and crash sites. I can visit the websites of small local historical associations and clubs dedicated to the aerial clashes that happened over a certain village or town and the crashes that ensued. In many cases these men and women, who do a better job of remembering lost Canadian airmen than we Canucks do, have done all the research already. Frequently, all I have to do is write the narrative and speak to the human cost and emotional wreckage.

When researching a story such like the crash of a Halifax bomber, I can find all the relevant information and images in less than a day, and from enough sources that I can corroborate facts and hear the story from different viewpoints. I can find images, write emails to other researchers, get answers, speak to people, and find connected material I might never have seen without the access afforded by the World Wide Web. It’s breathtaking really.

With short-sighted governments seeking to cut costs (at all costs), archives in many countries are hurting. Letters, logbooks, uniforms, medals and memoirs are fast becoming of passing interest to many archives and government museums, unless they are from a famous ace, a noted leader or celebrated aviator. The story of the ordinary Bomber Command airman is too granular for many organizations. These artifacts just take up space and government agencies can’t or won’t afford someone to appraise them and care for them. In many cases they could care less anyway, focused on sponsorship, fundraising and sustainability as they are. In the modern world, important information can be digitized and displayed online. Gone is the relevance of the physical object—the logbooks, the handwriting, the letters home.

Now, the World Wide Web has begun to collect this discarded and “unimportant” information. All over the world, from Russia to Australia, from Holland to Brazil, passionate aviation historians, memorialists, aero-geeks and romantics of every stripe have started their own personal archives; collecting, sharing, sorting, imagining, displaying and offering access to information in ways never imagined by archives and museums. There are forums dedicated to virtually (pun intended) any topic you can think of, from abandoned military airfields in the UK to Norwegian aircraft crash sites to the iconic Supermarine Spitfire to airline ephemera. These forums posit ideas, generate discussion, collect images, share data and corroborate facts. While they may be amateurs, they are no less relevant than big league history writers like Antony Beevor, Richard Ovary, Tony Judt or Margaret MacMillan.

Like many things on the web, there are good sources and bad sources, and if you spend enough time in and around them, you can sort them out pretty quickly. There are some virtual places where family members share the apocryphal, fanciful and often erroneous remembrances of fathers and mothers, but for dedicated researchers who want more than one source, or who know their material well, these emotional and honest, but wrong, sources can be almost immediately filtered. Often however, these poorly researched sites still can offer up a nugget in the form of rare family images and digitized logbooks.

The web, and the people who research within its ever-expanding universe, are fuelling a renaissance of sorts in historical research. More and more it seems that museums and archives no longer welcome such diversity and exchange. Archives (the formal type) are fast becoming well, archives—physical places where historical records are held and whose intake is now severely constricted. Happily, they are now all beginning to digitize and share some of the contents of their vaults.

Websites abound that are dedicated to the collection and sharing of information—production lists, Operations Record Books, images, and every imaginable detail of aviation history from airfields to aircraft carriers to insignia to letters. In fact, as I write this today, 4 May 2016, a group of Canadian aviation historians and enthusiasts are launching a new website dedicated to the goal of showcasing every aircraft ever listed in the Canadian Civil Aircraft Registry with histories of each aircraft and photographs where possible. It is a daunting task, but it starts today, and in the months and years ahead, it will no doubt, through contributions by third parties, take on a life of its own and become one of the many “go-to” websites for researchers in Canada. You would never get a government to build something like that.

The collecting of historic material, the exciting new ways to share this information and the people who do it are spread out across the world and linked by the internet. Where once the responsibility of assembling, caring for and sharing our rich national heritages were the responsibilities of centralized facilities and trained experts, a large part of it (the sharing of data and images) is now a cottage industry. Many of these cottage archivists are more passionate and more committed to the gathering and sharing of historical minutia than many government organizations have ever been. When you put a half million passionate people to work around the world, each with his or her narrow focus on a specific type, person, event, place or type and open the doors to everyone’s work, the result is the greatest and most accessible archive ever known to man. And here’s the best thing—it’s growing exponentially.

When I begin to assemble the facts and images to tell a story, I have at my disposal many cottage archivists whose work represents thousands and thousands of hours of dedicated sleuthing, processing and sharing. I still gratefully access the wonderful virtual and downloadable information from the excellent but more conventional archive centres like the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and the National Archives of the United Kingdom, but more and more I can find the corroborative and granular information or photographs I need from my brothers and sisters out there on the “interwebs”.

Some of these new virtual resources are not only great places to access information and imagery, they are delightful places to visit in and of themselves. One of the best and yet humblest of all my “go to” resources is the visual and historical archive known as 1000aircraftphotos.com, an ever-expanding photographic “stash” conceived of and built out by two very different men who live 5,000 miles apart.

In 1995, Oregonian Ron Dupas retired after a lengthy career in computing and website development. While Ron had a business career in computing, his lifelong passion was for aviation and in particular collecting aircraft photos, both print and digital. It was a natural extension of his working life to now spend time digitizing his vast collection and sharing it with the world at large via what he knew best—a website of his own. He had modest goals when he named his site 1000aircraftphotos.com. “I thought I would be doing well if I was able to get 1,000 of my photos on the site,” said Dupas. Going into its 18th year, 1000aircraftphotos.com has accepted more than 50,000 images from contributors around the world and, selecting the most suitable, is about to reach 13,000 pages on the site—a page deals with one particular aircraft type, variant or mark and many pages reference more than one image. The archive with 50,000 plus photographs is searchable by manufacturer and model, and registration if known. Many are other views of the same aircraft taken at different places and at different periods during their lifespan.

Related Stories

Click on image

The beauty of the internet (some say the opposite) is that content can begin to take on a life of its own. Once launched people like me, looking for images of a specific aircraft type, began coming across Ron Dupas’ little homemade website and before long, others were contributing to Dupas’ effort. It was important to protect the contributors from abuse of their photographs and to provide them with proper credit. Dupas explains: “From the very beginning, the site philosophy has been that contributed photos remain the property of the contributor and they receive credit for their photos and their information. Some contributors have delegated responsibility to us to approve use of their photos if asked, otherwise individuals asking to use photos are told to contact the contributors directly. We collaborate with contributors to make sure they are completely satisfied with the content and tone of the information they had provided before going live on the site.” In 2003, a Dutch aviation enthusiast and historian by the name of Johan Visschedijk came upon the site for the first time. Visschedijk, a perfectionist by nature with an encyclopedic mental databank of aviation minutia, noticed that Dupas had an incorrect designation on one of his entries and contacted him to set the record straight. Dupas, not one to be hurt by such critique, welcomed the correction and immediately asked Visschedijk if he would consider contributing some of his own photos.

1000aircraftphotos.com founder and constant, Ron Dupas started his project with the hopes of getting 1,000 of his collection of aircraft photos onto the net to share with other people. It went much farther than that. Here he is at 1000aircraftphoto.com’s North American headquarters—his desk. Photo: Martha Dupas

In May of 2003, Visschedijk’s first photographs appeared in 1000aircraftphotos.com… but alas, there was a problem. “When Ron processed my contributions, he changed dots to dashes and made various other edits of the information which I had supplied. I do not recall it exactly, but I emailed him (reportedly in no uncertain terms) that the information and designations I supplied were correct and should not be altered. In the end Ron asked me to join him with responsibility for accurate information and designations”. Dupas confirms Visschedijk’s firm admonition: “When Johan instructed me not to change anything he sent me about his photo contributions, it was with no room for disagreement. That was just the kind of person I like to work with, so began the process of sharing the administration of the site. That also began the evolution of the site from a photo site with information to an information site with photos. Our collaboration has evolved over time as we overcame the challenges of working together. The two main goals were to be able to work independently on our assigned areas to maximize individual initiative, and to devise a procedure to achieve zero error rates in administering the site.”

Johan Visschedijk of 1000aircraftphotos.com—driven, meticulous and omnipresent on the internet, writing, researching and sharing his vast knowledge of aircraft and aviation history and culture. Visschedijk’s aviation knowledge comes from a lifelong passion, but also from having been a documentation manager and aircraft recognition instructor with a Dutch aviation association. Photo: Jeroen Visschedijk

Two men working on the same material 5,000 miles apart have unique challenges, not the least of which was nine time zones. But the internet is about shared information, shared knowledge and shared responsibility—that’s why it will be the salvation of historical research. “Our first challenge was to overcome a 9-hour time difference.” said Dupas, “Files created by Johan had future times when they reached me. And files I altered to send back to Johan were older than the versions he had sent. We both attempted to update the website server and sometimes overwrote each other’s versions. Eventually we agreed only Johan would make updates to the server and I would institute procedures at my end to make sure file creation times would cease being a problem.”

Without getting too deep into the minutia of how Dupas and Visschedijk manage, update and grow the 1000aircraftphotos.com site, it is fair to say that they have worked out many of the kinks. They have deliberately maintained a simple and not-too-flashy design for the site, letting the images themselves be the stars. Each time an update is put online, followers get an email with links to a number of new and altered pages, in a quantity perfectly sized to digest at one viewing. Individual aircraft in each update are researched and supporting texts are written. Some of these take on lives of their own, like Visschedijk’s research on the rare Super V, a twin engine variant of the gorgeous V-tail Beech Bonanza. He recently completed his report after more than 80 hours on the project, with the goal to have the most comprehensive compilation of information about the type in the world. This author was proud to be able to scan some images from our library at Vintage Wings of Canada which filled in some gaps in the Super V story.

The modern historic aviation research centre and archive—no longer a centralized and imposing edifice in some nation’s capital, but simply a desk and a powerful personal computer linked to the World Wide Web. Of course, not seen here are the many shelves in Visschedijk’s home occupied by his extensive library of documents, periodicals and technical reports. There are a hundred thousand such centres around the world similar to this home office of 1000aircraftphotos.com’s Johan Visschedijk. Photo: Johan Visschedijk

While Dupas and Visschedijk are the “faces” of the website, it is, like much of the World Wide Web, a collaborative workspace that welcomes the contributions of others. Some of these now more than 400 collaborators have similarly-sized collections and have contributed huge sections to the website. Jack McKillop, for instance, has provided images and information for over 750 pages on the site and Walter van Tilborg more than 300. Photo-editor Aubry Gratton has processed hundreds if not thousands of images for the site. The work continues on all fronts and with much collaborative input from around the world. It is this sense of something greater than themselves that inspires these two men to continue their important work and fuelling the site’s prodigious output.

On several occasions, the World Wide Web has come knocking on 1000aircraftphotos.com’s virtual door looking for help— sometimes to identify aircraft in photographs, sometimes to assist in identifying the recently discovered remains of a long forgotten aircraft tragedy.

Like many relationships that begin on the internet, it was only a matter of time before the new friends would meet in person. Despite the extreme distance that physically separates the two men, they have both taken the time over the past 13 years to visit each other several times. Theirs is a friendship and shared passion that has given the world of aviation researchers and enthusiasts a powerful tool and a lasting legacy—one more incredible building block in our understanding of aviation history. If anything else, I guarantee you that in just a few clicks of your mouse, you will see and learn about aircraft types you have never seen before.

The internet is a marvelous place indeed. It is so because of men like Ron Dupas and Johan Visschedijk, whose passion, work ethic and desire to honour and share have created and continue to create a magical world where anything is possible. Despite, or maybe because of cutbacks in traditional archives and information sources, we now have a much better way forward—one that involves all of us in building knowledge and sharing it in much more creative ways. Who better to remember and celebrate the aviators who have gone before us than all of us together?

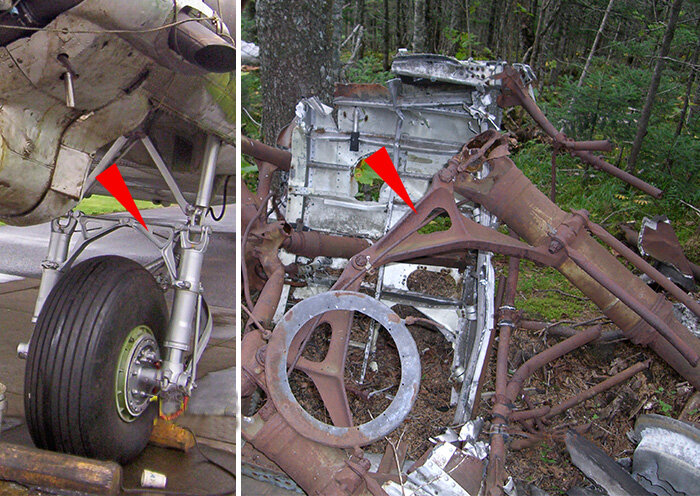

In the same way that I came upon 1000aircraftphotos.com, so did Lieutenant Colonel Tim Hall (above) of the United States Department of Defense. Colonel Hall’s job is to find, identify and bring home as many of the more than 88,000 Americans still “Missing in Action”. As such, he visits many crash sites around the world to determine if the aircraft is American and if so to look for human remains or personal effects. In 2007, Hall wrote to Visschedijk with a request to identify wreckage he was working on in the forests near Vladivostok, Russia. It took Visschedijk only a few minutes to determine that this wreckage was from a Douglas DC-3—the landing gear had a very distinctive structure. Because he had been an aircraft recognition instructor with the Dutch Air Training Corps and had spent a lifetime looking at aircraft images, he could make a definitive judgement right away. Since there were no reported American DC-3 aircraft missing near Vladivostok, Hall called off the search for human remains, and closed the book on the site as far as America was concerned. Photo via Lt. Col. Tim Hall

Lt. Col Tim Hall sent Visschedijk several photos of the wreckage he was investigating in the boreal forest around Vladivostok. He asked the Dutchman if he could identify the type based on the broken remains. Photo via Lt. Col. Tim Hall

It took Visschedijk only a couple of minutes to identify the aircraft through distinctive components of its landing gear. Photo via Lt. Col. Tim Hall

A sneak peek at the pages of 1000aircraftphotos.com

Like the monthly update I receive from 1000aircraftphotos.com, I have selected a number (50 to be precise) of aircraft that are covered in the vast and expanding visual archive that is 1000aircraftphotos.com. I selected them from the thousands to be found there for a wide variety of reasons, but largely they are rare aircraft not usually thought of by even self-described aviation aficionados. Above all they are quirky and largely unsuccessful. That is one of the wonderful things about the site—aircraft just have to have wings and be designed to fly to get recorded and displayed on 1000aircraftphotos.com. In fact, several of these 50 did not fly at all. A few killed the first pilot who tried to master them. Fifty aircraft is about all you can consume in this one story, but it represents only 0.38% of the types you will find in the pages of the website. Enjoy this tiny selection for what it is, but I strongly recommend that you spend an hour one evening and click your way into aviation history and culture with its magnificent failures and its historic icons. It’s not flashy, it has no gimmicks, no ads, no interactivity, no social media links—just superb and accurate content and an aviation revelation around every corner. And if you find that an aircraft is not accounted for, send them a photo of it.

Icarian obsession. One of the most poignant, yet sadly inspiring stories of aviation is the tragedy and blinding obsession of Leonard Bonney, an aviation pioneer and one-time First World War US Army and Navy flying instructor. Bonney became obsessed with the shape of a gull’s wing, which he believed to be the most efficient and capable wing form in nature. He set out to design an airplane that mimicked its qualities. Through mechanical mechanisms he sought to be able to vary the wing’s incidence and sweep—advanced technology that would not really come to fruition for many decades. But not in 1928. The design, wind tunnel testing and fabrication of the Bonney Gull took him almost five years. At a time when a new airplane cost about $3,000, the Gull’s $83,000 development cost was an indicator of Bonney’s unflinching obsession. The aircraft had so many new features and looked so unpredictable that Bonney could not get a test pilot to take it up—so he did it himself. On 4 May 1928 at Curtiss Field, Long Island after a quick flight in another aircraft to refresh his skills, he took the Gull into the air on its first flight—and killed himself. At a height of about 50 feet, the porpoising aircraft nosed over and dove straight into Long Island. Five years in the making and it took just five seconds to end it. For a tragic newsreel of Bonney’s last moments, click here. Photo: Leslie Jones via David Horn Collection

The Henschel HS 124 V1 was a prototype “Kampfzerstorer” or heavy fighter-bomber concept from the early Luftwaffe at a time when the development and rearmament of the Luftwaffe was largely a clandestine affair—hence the lack of Luftwaffe makings and swastikas. While the type held some promise, the role of Kampfzerstorer fell to the impressive and ultimately iconic Messerschmitt Bf 109. Only three prototypes were constructed, each with different engines—here we see the V1 variant, powered by two liquid-cooled Jumo V-12 engines. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

Many, if not most, of the great early helicopter designers were Russian—Igor Sikorsky, Nikolai Kamov, Mikhail Mil and Ivan Bratukhin, the designer of the Bratukhin Omega II. As with other early helicopter designs, the Omega II was first “captive” tested using a tether to prevent it losing control at a dangerous altitude. The design bureau was evacuated ahead of the German advance and it was months before development could continue and testing proceed. In this image, which I believe comes from a newsreel, the observer descends a rope ladder to the ground. It appears that there is no pilot, but he is behind the door. On YouTube you can find a video of the Omega being demonstrated at an airshow in 1945 plus other footage of the Omegas. Click here to see the film. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The Doman LZ-5 was an American designed utility helicopter. The type, designed by Glid Doman and first built in Danbury, Connecticut, was evaluated by the United States Army as the YH-31. Johan Visschedijk explains the Canadian registration on this American-built helicopter: “Doman and Fleet Manufacturing, Ltd. of Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada had formed Doman–Fleet Helicopters. The US-built development aircraft N812 was transferred to Doman–Fleet at Fort Erie and after some minor modifications it was flown in 1955, operating under a Canadian experimental flight permit, hence registered CF-IBG-X. With its 7 ft (2.13 m) wide doors removed on both sides the helicopter showed in mid-1956 its capability of lifting bulky cargo without slings by transporting a 1,900 lb (862 kg) cabriolet Volkswagen.” The promotional stunt impressed the author enough to put the Doman into this story 60 years later. Though only three LZ-5s were built, this same Doman plus a YH-31 US Army variant exist today and can be viewed at the New England Air Museum in East Granby, Connecticut. Photos: Top: Ray Watkins Collection, Bottom: Johan Visschedijk Collection

The one-off Curtiss XF14-C. On the date that the USN let a contract for its development, they also issued contracts to Grumman which ultimately would result in the Hellcat and the Tigercat. While these two Grumman cats would go down in naval aviation history, the Curtiss fighter would fail to live up to its designers’ predictions. 1000aircraftphotos.com writes: “On 30 June 1941, Curtiss was awarded a development contract for the XF14C-1 single-seat high-altitude shipboard fighter, to be powered by the still experimental 2,200 hp Lycoming XH-2470-4 liquid cooled engine. Wind tunnel tests conducted by the Navy in October 1942 indicated that Curtiss engineers had been somewhat optimistic in their performance estimates, inadequate by contemporary standards. This, and the still existing prejudice by the Navy against liquid-cooled engines, led to the cancellation of the XF14C-1. However, Curtiss was requested to adapt the airframe for the turbo-supercharged 2,300 hp Wright XR-3350-16 two-row eighteen cylinder air-cooled radial engine, driving a six-bladed contra-propeller. Designated XF14C-2, the aircraft was flown in September 1943, but not delivered to the USN until July 1944. The XF14C-2 performance, too, was below manufacturer’s guarantees, and with the tide of war in the Pacific running in favour of the USA, the altitude capability needs diminished.” Photos: Top: Johan Visschedijk Collection, Bottom: Bill Pippin Collection

No aircraft better represents the glories of civil aviation before and after the Second World War than the transoceanic flying boats with their magnificent size and first class service. Of all the flying boats, the French Latécoère 631 was perhaps the most beautiful, if far from the safest. Her beautiful lines and gargantuan size were literally breathtaking. In all, ten production 631s were built after the prototype first flew—in 1942 at the height of the war. Following the 631’s successful first flight, the Nazi’s commandeered it and flew it to the Bodensee (Lake Constance) on the German–Swiss–Austrian border. In 1944, it was attacked and destroyed at anchor by RAF Mosquitos. Despite the war raging through France, Latécoère managed to complete the first production model in March 1945, now powered by Wright Cyclones instead of its original Gnome et Rhône engines. Four following production models were bought by Air France which operated them on the France–Mauritania route. Other operators were SEMAF (Société d’Exploitation du Matériel Aéronautique Français) and SFH (Société France Hydro). In October of 1945 a propeller on F-BANT (seen here) separated in flight with a blade slicing through the cabin and killing two passengers. In February of 1948, F-BDRD crashed in the English Channel during a snowstorm killing all 19 on board. In August of the same year, F-BDRC disappeared over the eastern Atlantic with no survivors being found. In March of 1950, F-BANU was lost off the coast of France, again with no survivors and finally in 1955, SFH’s F-BDRE had a wing failure, crashing with the loss of half of the 16 people on board. France and the world had had enough. Thankfully, the Latécoère 631 never flew again. For a newsreel of the first flight of the 631 (wearing D-Day Invasion stripes as likely the war was still on), click here. Photos: Nico Braas Collection

No aircraft better represents the glories of civil aviation before and after the Second World War than the transoceanic flying boats with their magnificent size and first class service. Of all the flying boats, the French Latécoère 631 was perhaps the most beautiful, if far from the safest. Her beautiful lines and gargantuan size were literally breathtaking. In all, ten production 631s were built after the prototype first flew—in 1942 at the height of the war. Following the 631’s successful first flight, the Nazi’s commandeered it and flew it to the Bodensee (Lake Constance) on the German–Swiss–Austrian border. In 1944, it was attacked and destroyed at anchor by RAF Mosquitos. Despite the war raging through France, Latécoère managed to complete the first production model in March 1945, now powered by Wright Cyclones instead of its original Gnome et Rhône engines. Four following production models were bought by Air France which operated them on the France–Mauritania route. Other operators were SEMAF (Société d’Exploitation du Matériel Aéronautique Français) and SFH (Société France Hydro). In October of 1945 a propeller on F-BANT (seen here) separated in flight with a blade slicing through the cabin and killing two passengers. In February of 1948, F-BDRD crashed in the English Channel during a snowstorm killing all 19 on board. In August of the same year, F-BDRC disappeared over the eastern Atlantic with no survivors being found. In March of 1950, F-BANU was lost off the coast of France, again with no survivors and finally in 1955, SFH’s F-BDRE had a wing failure, crashing with the loss of half of the 16 people on board. France and the world had had enough. Thankfully, the Latécoère 631 never flew again. For a newsreel of the first flight of the 631 (wearing D-Day Invasion stripes as likely the war was still on), click here. Photos: Nico Braas Collection

The Caudron C.530 Rafale was a French two-seat competition aircraft. Only seven were built but they had great success in several contests during 1934. The Rafale (a French word meaning “gust of wind”) was intended as a competition aircraft and in 1934 it was very successful. On 8 July, Rafales took the first three places in the Angers 12-hour event and later that month filled the top six Esders Cup positions. Late in August, one won the Zénith Cup with a flight over the prescribed 1,578 km (981 mi) course at 240 km/h (149.1 mph). The Rafale’s two seats were in tandem, one over the wing and the other just behind the trailing edge, under a long (about a third of the fuselage length), narrow multi-framed canopy with a blunt, vertical windscreen and sliding access. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

Designed and built in 1935 by Hayden Campbell in St. Joseph, Missouri, the Campbell F was made of all-magnesium construction and was powered by an 85 hp Ford V-8 automotive engine. It’s not difficult to see why it had earned the nickname The Flying Easter Egg. The aircraft was damaged in a demonstration flight and never repaired. For a lovely little video of the Campbell F warming up and in flight in Missouri, click here. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

Armstrong Whitworth’s third airliner type, the Ensign, was the largest machine built in pre-war days for Imperial Airways Ltd. and, like [its predecessor] the Atalanta, was a four-engine high-wing cantilever monoplane designed by John Lloyd. There the similarity ended, the newcomer being of almost twice the physical size, three times the all-up weight, of all-metal stressed skin construction, and fitted with an enormous retractable undercarriage. Power plants were four 850 hp Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX engines. It carried 27 passengers in three cabins and was intended for the distant Empire routes, sleeping accommodation being alternatively provided for 20. One promotional newsreel of 1937 stated that the Ensign was “a new streamline monster in the Empire skyways”. For another period newsreel about the Ensign, click here. Photo: Alfarrabista Collection

Many of the rare aircraft types listed in the pages of 1000aircraftphotos.com were never meant for production. Many, like this Hunting H.126, were simply designed and built to test a new concept, principle or technology. Hunting Aircraft’s H.126 was “a single-seat research aircraft which had been built to flight test the jet-flap principle [widely called “blown flaps” today]. In this, the exhaust efflux of a turbojet engine is ducted to the trailing edge of an aircraft’s wings and ejected through a narrow slit along the trailing edge. As well as being used to provide propulsion, the efflux can be deflected downward to form a “jet-flap” of high velocity gas which makes possible the achievement of lift coefficients of 10 or more.” The aircraft was designed purely for test purposes and thus lacked features such as retractable landing gear. The shoulder-level wing featured a set of struts, not for support but in order to provide piping for the compressed air used in the blown flaps. The sole H.126 flew for the first time on 26 March 1963, and had completed over 100 test flights by mid-1965 with the program ending in 1967. After two years storage it went to NASA in the USA in 1969, returning in May 1970. Stored for another two years it was struck off charge in September 1972 and is presently on display at the RAF Museum, Cosford. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

With such an evocative and powerful name, the Westland Dreadnought seemed poised on the edge of a new era in aircraft design. Sadly, the Dreadnought never came close to living up to its name. The ship was an “experimental single-engined fixed-wing monoplane design for a mail plane created to trial the aerodynamic ‘blended’ wing and fuselage design ideas of Russian engineer M. Woyevodsky. It was designed and built by British aircraft manufacturer Westland Aircraft for the Air Ministry. On completion of the Dreadnought, pilot Arthur Stewart Keep carried out taxi trials and short airborne hops. On 9 May 1924, he took off for its first flight test. While the aircraft was initially stable, it soon became clear that Keep was losing control, and not long after, at a height of approximately one hundred feet, the Dreadnought stalled and crashed. Thrown from the aircraft, Keep sustained severe injuries, and later had both legs amputated. He remained with the company and did not retire until 1935. After this failure, the Dreadnought design was abandoned, although the ideas that were conceived and used in its making were visibly an advancement in aircraft and are appreciated as such in the present day.”—Wikipedia. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The Vickers 161. Designed from the get-go as a gun platform for a 37 mm gun designed by the Coventry Air Works (COW), the Vickers 161 was extraordinary in its configuration. The website aviastar.org states: “An unequal-span two-bay biplane with comparatively high aspect ratio wings with duralumin plate and tube structure, it had a metal monocoque nacelle, accommodating the pilot to port and the COW gun to starboard, which was faired into the upper wing and raised above the lower wing by splayed N-type struts. The 530hp Bristol Jupiter VIIF nine-cylinder radial carried at the rear of the nacelle drove a four-bladed propeller, aft of which was a curious, long tapered cone which, intended to promote directional stability, was supported by struts from the tubular tail-booms and the tailplane. The Type 161 was flown for the first time on 21 January 1931, and after provision of a broader-chord rudder, it flew extremely well, arriving at Martlesham Heath in September 1931 for official evaluation. Development was discontinued when official interest in promoting the quick-firing COW gun lapsed.” The COW 37 gun was to protrude at a 45 degree angle from the nose and was designed to shoot down bombers. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The Vultee V-11 two- and three-seat light bomber—selected for this story simply because I loved the extra long greenhouse canopy. While Vultee designed aircraft with the hopes of building them for the United States Army Air Corps and the United States Navy, some, like the Vultee V-11 were of not much interest to American forces, but saw some service with foreign air forces. While the USAAC would later purchase 7 Vultee V-11s (calling them the YA-19) to compare with other aircraft of the day, there was some interest from foreign governments whose air forces were just beginning to grow. China ordered 30 two-seat Vultee V-11s and then more Vultee V-12s (a more powerful variant) which they were planning to assemble from kits (25 were finished), Brazil acquired a total of 26, Russia bought or built a total of 34 and Turkey purchased 40. The aircraft had limited combat success with the Chinese, and a Brazilian Vultee V-11 made an attack on a submarine, damaging itself in the process. Later developments would have a rear facing gunner at the back of the cockpit plus a rear-facing ventral gun position protruding from the bottom. Most were later used as high speed liaison and transport aircraft. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

A later development of the Vultee V-11 was the V-12, a streamlined and attractive alternative to the largely unsuccessful type. First flown in September 1938, the prototype aircraft (NX18985) was sold to Pratt and Whitney aircraft as a test bed. Photo: Curtiss Aldrich Collection

The Convair Liberator–Liner. Johan Visschedijk of 1000aircraftphotos.com writes: “Consolidated foresaw a market for a large transport to be used by both civil and military operators and started the design as the Model 39 in early 1943. After the merger of Consolidated and Vultee the type was continued as the Convair Model 104. Convair was the trade name of Consolidated Vultee after the 1943 merger. To produce an aircraft in a short time it became a hybrid: the wings, engines, single vertical tail and landing gear of the PB4Y-2 Privateer (the ultimate US Navy version of the B-24 Liberator) were mated to an entire new circular-section fuselage. The US Navy became interested and signed a letter of intent for 253 aircraft in March 1944. The first prototype NX30039 (c/n 1) was flown for the first time on 15 April 1944 piloted by Phil Prophett and his crew. Due to design deficiencies the Navy cancelled its order but Convair received permission to purchase and complete the second prototype in Navy colours. Thus the second aircraft was completed as the Convair 104 XR2Y-1 and fitted with R-1830-65 engines NX3939 (c/n 2) and made it first flight on 29 September 1944. Eventually this aircraft was given the US Navy registration 09803. American Airlines operated the first aircraft, named City of Salinas (top), with the support of Convair for three months transporting fresh fruits between Salinas and El Centro, California and cities in the east like Boston and New York. In airline service the Liberator–Liner would have carried 48 seated passengers or 24 in sleeping berths. A cargo of 18,500 lb (8,392 kg) could be loaded straight from flat trucks into the aircraft through large fuselage doors. However, the type could not compete in performance with, and was much less powerful than current aircraft and as there was no other interest in the design both aircraft were scrapped in 1945.” Photos: Top: Walter van Tilborg Collection, Bottom: Ron Dupas Collection

The late 1940s and early 1950s were some of the most exciting and creative times in aviation design and development. There were many players throwing out new design concepts almost daily and the breadth of thinking was astonishing, even if some of the concepts were dead ends. No company better expresses the creativity of the times that Convair, the company which came out of the merger between Consolidated and Vultee. Their designs responded to the times and, unlike other manufacturers, occupied nearly every area of aviation—from the great bombers of Strategic Air Command (SAC) like the transitional behemoth and ironically named B-36 Peacemaker and the wickedly aggressive-looking B-58 Hustler, to the last of the thinking on seaplane technology like the Sea Dart fighter and elegant Tradewind flying boat, to jet fighters that sustained the air force and air guard units for decades like the Delta Dagger and Delta Dart, and finally to the airliners—the sleek 880s and 990s and the highly successful early feeder liners like the Metropolitan and Cosmopolitan. Amidst all their successes was the slender four-engined XB-46 (pictured), an experimental jet-powered medium bomber. The type was developed in the mid-1940s, and despite its futuristic appearance, flew for the first time as early as 1947. It was competing against similarly configured experimental bombers such as the North American XB-45 Tornado and the Martin XB-48. While the Tornado was first to limited production with 143 examples built, they were all eclipsed in the end by the magnificent and inspiring Boeing B-47 Stratojet of which more than 2,000 were eventually built for SAC. The XB-46 was cancelled in the same year the single copy was built—1947. Click here for a video of the type in flight. Photos: Top: Ron Dupas Collection, Bottom: Walter van Tilborg Collection

During the 1920s and 1930s, the world was obsessed with air racing and as a result, the science and art of aircraft design took huge leaps and bounds as designers sought to make their race planes faster and lighter. Thanks to air racing and the Schneider Cup, the Spitfire was born. So were any number of tiny aircraft like the Haines H-3 Mystery Ship (sometimes called the Special or Firefly), designed and flown by Frank Haines in the 1937 Greve Trophy Races. The race was ten laps of a ten-mile course, with a $15,000 purse. The Haines H-3 was sixth and dead last. The aircraft’s forward raked windshield and tiny rudder are notable features of Haines’ design and give it a speedy look. Haines was killed in the H-3 on 3 December of that same year in Miami as the race began. At virtually the same moment (but not a related incident) Rudy Kling, the 1937 Thompson Trophy winner lost control of his ship and was also killed. It was thought they were both caught by the same wake turbulence or downdraft. According to newspaper articles, both aircraft were set on fire at the end of the day to get rid of the wreckage—so much for a crash investigation! For a fun video of a rubber band model of the Haines H-3 in flight, click here. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

The Handley Page H.P.75 is the type of airplane one might see in an Indiana Jones movie—one that breaks all the control configuration paradigms at once. Johan Visschedijk elaborates on the type. First known as the “Tailless Research Aircraft” [hence the name Manx—the tailless cat -Ed] this aircraft was designed by Dr. Gustav Victor Lachmann to investigate the problems associated with tailless aircraft. The airframe was built by Dart Aircraft of Dunstable, England; the aircraft was finished at Radlett, England. During taxi trials on 12 September 1942, the aircraft flew unintentionally at a height of 12 ft (3.66 m) and was subsequently damaged while landing. Marked with the ‘Class B’ markings* H-0222, the aircraft flew for the first time on 25 June 1943. In 1945 it was designated H.P.75 for the first time. A total of 31 flights were made till 3 April 1946 (total flight time 17 hr 43 min) when the aircraft was stored and subsequently scrapped in 1952. * British aircraft test serials (in this case HO222) are used to externally identify aircraft flown within the United Kingdom without a full Certificate of Airworthiness. They can be used for testing experimental aircraft or modifications, pre-delivery flights for foreign customers and are sometimes referred to as “B” class markings. Photos: Bernhard C. F. Klein Collection

The one-off Hawker Hotspur turret gun fighter (K8309) was designed by Sydney Camm of Hurricane fame. 1000aircraftphotos.com explains: “K 8309 was the only Hawker Hotspur built. It was derived from the Hawker Henley which was originally planned as a two-seat light bomber, but went into RAF service as a target tug. The Hotspur was Hawker’s response to the request for a turret fighter, but the contract was placed with Boulton Paul resulting in the Defiant. The concept of the turret fighter did not prove successful; so many Defiants were converted to target tugs and replaced the Henleys. Although better as a target tug than the Henley, the Defiant was still far from perfect. The RAF finally got its first purpose-designed target tug in the form of the Miles Martinet.” The aircraft first flew in June of 1938, but with a ballasted wooden mock-up of the Boulton Paul powered turret envisaged for the final production models. The entrance door for the turret gunner can be seen below the turret in this image. The single airframe (K8309) was later painted in the standard RAF camouflage and yellow test markings for its trials. Photo: Jacques Trempe Collection

First developed as a response to an Air Ministry requirement for a light bomber with good enough performance to be used as a dive bomber for close air support, the Hawker Henley would eventually be built for an entirely different role. Eventually the requirement for the light bomber was dropped, but the Henley found a new and less glorious calling as a target tug. More than 200 were built, but in the end the type proved ill-suited to the task, with many engine failures due to a cooling system which performed best at high airspeeds not suitable for target towing. They ended their short careers towing the larger drogues for training anti-aircraft gun crews. Several aircraft were lost when the engine quit but the drogue could not be released fast enough. They were withdrawn from service in 1942. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

The sleek and powerful-looking S.E.1010 was a late 1940s French photo-survey aircraft designed and built by SNCASE for the Institut Géographique National. Johan Visschedijk writes: “Ordered by the French Ministère de l’Air (Ministry of Aviation) the S.E.1010 high-altitude photographic survey aircraft was designed and constructed by the SNCASE (Société Nationale de Constructions Aéronautiques du Sud–Est) at Marignane. Powered by four 1,590 hp SNECMA (previously Gnome–Rhône) 14R-28/29 radials and registered F-WEEE, the aircraft was first flown from Marignane by a crew led by test pilot Jacques Lecarme on 24 November 1948. Construction of a small production batch was started in 1949. During a test flight on 1 October 1949, the aircraft entered a flat spin, from which it did not recover, the six crew were killed, including test pilot Henri Vanderpol. Subsequently the Ministère de l’Air revised its opinion of piston engines on future aircraft and the project was abandoned.” Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

The pre-war French aviation industry loved unconventional design, and the insectoid SNCASE S.E.100 is a case in point. The S.E.100 was a French two-seat, twin-engined fighter which first flew in 1939. In plan, the aircraft looked rather conventional, but it was not (visit the 3-view drawing at 1000aircraftphotos.com). The fuselage was short in appearance, with a long nose and a very short tail, the cockpit being connected to the gunner’s position aft by a windowed corridor. The undercarriage was of the nose wheel type, rarely used in French aircraft of the 1930s, with the main wheels fitted right aft, retracting into the tail rather than the wings or engine nacelles as was conventional. The aircraft was fitted with four Hispano–Suiza HS.404 20 mm cannon in the nose and one in the gunner’s post... The first prototype of the S.E.100 flew on 29 March 1939 at Argenteuil and a number of necessary changes were identified during the tests. It was destroyed in a crash on 5 April 1940.The aircraft proved to be around 100 km/h faster than the Potez 631, the French Air Force’s current twin-engined fighter, and production was authorized. Mass production was planned to begin late in 1940 but the fall of France prevented further development and production. (Text assembled via Wikipedia) Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The single prototype Sud–Ouest SO-30R Bellatrix with Hispano–Suiza-built Rolls–Royce 101 Nene engines. The type was a jet development of Sud–Ouest’s Bretagne propeller-driven medium airliner. While the propliner had a production run of 45 aircraft, only one test aircraft with jet power was built. Another (or possibly this same airframe) was re-engined with the SNECMA ATAR jet engine. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The SNCASO SO.4000 from la Société Nationale des Constructions Aéronautiques du Sud–Ouest, commonly known as Sud–Ouest, had a big promising name and less than excellent performance judging by its short-lived flying career. Although planned production of the type was already cancelled, it was decided to build out two scaled models (one a glider, the other powered) and the prototype. The landing gear proved to be its Achilles heel, collapsing during taxi tests, repaired and then failing again upon landing. The project was then abandoned. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The Jovair 4A—short, stubby and cheerfully stylish in a Bruce McCall/The New Yorker magazine sort of fashion. Ray Watkins tells us in 1000aircraftphotos.com: “The Helicopter Engineering Research Corp was formed in 1947 by D.K. Jovanovich and F.J. Kozloski who were former employees of the Piasecki Helicopter Corp. Their first design, the two-seat tandem rotor Jov-3, flew in 1947. The company was renamed J.O.V. Helicopters in 1948. The design rights were sold to McCulloch Motors in the same year for their new Helicopter Division, with Jovanovich as Chief Engineer. McCulloch continued development of the Model Jov-3 to produce the McCulloch MC-4, which first flew in March 1951 and received FAA certification in 1953. In 1952 the US Army purchased three examples of the MC-4C, which had small endplate rudders at the rear of the fuselage, for evaluation as the YH-30. Jovanovich and Kozloski left McCulloch when the Airplane Division was closed, and formed Jovair Corp in 1957 to continue their work on helicopters. They resumed the design rights and purchased one of the MC-4A’s (N4071K) which had been produced for evaluation by the USN (as the HUM-1). The Jovair 4E Sedan was an enlarged 4-seat version of the MC-4C which received certification in March 1963. It was the last design produced by Jovair and the design rights reverted to McCulloch in 1969 who continued development of the Jovair 4E Sedan as the McCulloch MC-4E. The picture shows the four-seat 4E Sedan with the 1962-built Jovair 4A, a stripped-down two-seat agricultural and training aircraft, in the background.” Photo: Ray Watkins Collection

The Abrams P-1 Explorer (X19897). Wikipedia explains the little one-off aircraft: “The Abrams P-1 Explorer was an American purpose-designed aerial photography and survey aircraft that first flew in November 1937. It was designed by aerial survey pioneer Talbert Abrams to best suit his needs for a stable aircraft with excellent visibility for this kind of work. Abrams was an early aerial photographer in World War I. He used a Curtiss Jenny postwar, forming ABC airlines. In 1923 Abrams founded Abrams Aerial Survey Company, and in 1937 Abrams Aircraft Corporation to build the specialized P-1 aircraft... The Quarterly Journal of the American Society of Photogrammetry said, “this new craft is so unique in design as to resemble the mythical creation of a ‘Buck Rogers’ space ship of the year 2040.” Today, the Explorer is stored with the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, awaiting restoration. Photo: Loet Kuipers Collection

The delightful Airspeed AS.5 Courier was selected for this story simply because it looked smart in its deco livery (in silver and burgundy), retractable gear and wide expanse of glazing. 1000aircraftphotos.com states: “This is the prototype of the Courier, pictured on her first flight from Portsmouth on 11 April 1933. Four days later it crashed at Portsmouth, receiving minor damage. Repaired, it had another accident at RAF Martlesham Heath. It was used in aerial refuelling experiments by the well-known British aviation pioneer Sir Alan Cobham, using two Handley Page W10s as aerial tankers. The experiments led to an attempt of a non-stop flight to India that started at Portsmouth on 24 September 1934. It ended the same day when Cobham had to make a forced landing at Malta, due to a broken throttle; in the event the Courier was damaged. The aircraft was impressed into the RAF in June 1940, s/n X9427. The fate of the prototype aircraft is unknown,” but a total of 15 production aircraft ensued. Photo: David J. Gauthier Memorial Collection

Of all the names of aircraft I have studied over the years, perhaps the least inspiring of all was the ATL-90 Accountant from Freddy Laker’s Aviation Traders. It was not an unattractive aircraft with its massive tail and purposeful stance in the air, but if ever there was a name that failed to evoke any excitement or emotional response to the burgeoning field of postwar civil aviation, it was the Accountant. The first prototype and only Accountant ever built was flown for the first time in 1957. Built by the very reputable Aviation Traders Limited, builders of the famous Carvair conversions of Douglas DC-4s, the Accountant was demonstrated at Farnborough, but failed to gain any interest whatsoever. Two years later, it was scrapped. Photo: Walter van Tilborg Collection

The Avtek 400 ignored many conventional design configurations at one time. With its over the wing pusher propellers, high mounted forward canard, bizarre wing shapes, all-Kevlar construction and lack of elevators, perhaps it offered just a bit too much change for aircraft buyers. The late Bernhard Klein in 1000aircraftphotos.com wrote: “This was the proof of concept aircraft of a six/nine-seat pusher turboprop-powered business aircraft, with a crew of one or two pilots. It was the first US aircraft constructed throughout from DuPont ‘Kevlar’ advanced composite material, hence the ‘DUPONT’ logo on upper sides of the tailfin. First flown in the USA on 17 September 1984, the type never went into production, and the company went bankrupt in 1998. The aircraft appeared in the ‘Airwolf’ TV series as the X-400, the plane used by the villain Lou Stappleford in the episode ‘Eagles’.” For more on the fate of the Avtek 400, click here. Photo: Bernhard C.F. Klein Collection

The Hirsch–MAéRC H-100 was a one-off research aircraft designed by Frenchman René Hirsch to test his system to deal with gusts that make for bumpy and uncomfortable flying. Walter van Tilborg writes on 1000aircraftphotos.com: “It incorporated a system in which the halves of the horizontal tail moved on chordwise hinges to operate flaps on the wings. The conventional elevators provided not only pitching moments, but moved the tail halves about their chordwise hinges to cause the flaps to move in the direction to provide direct lift control. In this way, the loss of longitudinal control due to the gust-alleviation system was overcome. Of wooden construction, the H-100 incorporated many other ingenious features, including swivelling wingtips for reducing rolling moments due to rolling gusts and lift due to horizontal gusts. The design also incorporated large pneumatic servos operated by dynamic pressure to restore damping in roll and to stabilize the rate of climb or descent.” The single aircraft built was retired after 130 test flying hours and was then donated to the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace, at Le Bourget, Paris, where it remains on display. Photo: Pierre Bregerie Collection

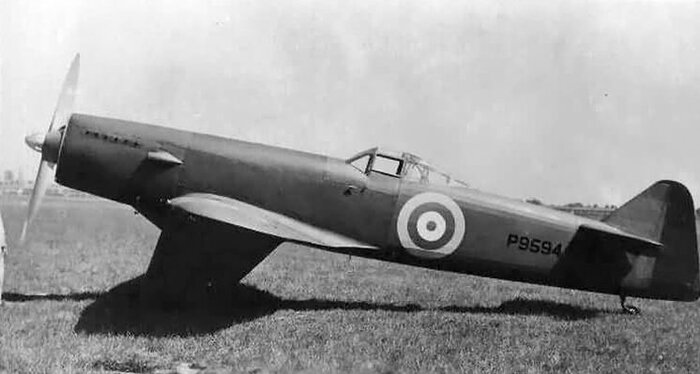

The Martin Baker M.B.2. Johan Visschedijk of 1000aircraftphotos.com writes “Designed by James Martin with the collaboration of Captain Valentine H. Baker, the M.B.2 was built to conform to the requirements of Specification F.5/34, but funded as a private venture. Conceived for manufacture in large numbers by semi-skilled workers at low cost, the M.B.2 employed a steel-tube structure with fabric skinning, was powered by a Napier Dagger III 24-cylinder H-type engine with a rated output of 798 hp at 5,500 ft (1,675 m), and carried an armament of eight 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning guns in the wings. The depth of the fuselage was virtually constant from nose to tail and vertical tail surfaces were eliminated, the rudder being hinged to the sternpost behind the elevators. First flown by Captain Baker on 3 August 1938, registered G-AEZD and marked M-B-I, the M.B.2 demonstrated serious directional instability and a rudimentary fixed tailfin was immediately introduced. While tested at Martlesham Heath, a level speed of 320 mph (515 km/h) was recorded with full armament, but official reports of trials, while enthusiastic concerning its engineering design, pronounced the M.B.2 unstable about all axes and generally unpleasant to fly. An unorthodox feature was the retractable crash-pylon which automatically extended behind the pilot’s head in the event of a nose-over. In March 1939 it was handed over to the RAF, s/n P9594, while in May 1939 more orthodox vertical tail surfaces (shown above) were fitted, these markedly improving handling, but the RAF evinced no interest in the fighter, development being discontinued, and the aircraft was broken up at Denham.” Photo: Bill Pippin Collection

The Martin–Baker M.B.3 was a powerful and promising British fighter aircraft prototype designed around the complex 2,000 hp Napier Sabre engine and first flown in August of 1942. The production aircraft was to have an astonishing punch—six 20 mm cannons. Test flights conducted by company partner Valentine Baker showed that the M.B.3 was highly manoeuvrable and easy to fly. Sadly, on 12 September 1942, the engine failed soon after takeoff and Captain Baker, attempting to save the aircraft during the difficult forced landing, crashed in a field and was killed. Baker’s death devastated his partner James Martin, who eventually abandoned the project even though it held such promise. It is said that the accident started Martin’s new passion for safety systems and air crew survivability and led to the development of the now-famous and ubiquitous Martin–Baker ejection seats. Photo: Jacques Trempe Collection

Here is one airplane that in no way lives up to its euphonious and alliterative name—the McCarter Meadowlark. The swift flying, darting and sleek meadowlark with its buoyant song brings to mind something far different than this aircraft, looking part farm tractor, part toy glider, part ice box. Photo: Walter van Tilborg Collection

To the average person claiming to know something about British aviation history during the Second World War, the name “Miles Aircraft” will barely register, if at all. While names like Supermarine, Hawker, Avro, Handley Page, Bristol and de Havilland absorbed most of the limelight with their now legendary combat aircraft designs, Miles laboured tirelessly and quite successfully “in the wings”, designing and manufacturing aircraft absolutely vital to the outcome of the war. These were flight training aircraft like the Miles Magister elementary flight trainer, the Miles Master advanced flight trainer and the purpose-built Miles Martinet target tug—totalling more than 6,000 aircraft built. Miles Aircraft prepared RAF pilots and gunners to fight and ultimately defeat the Nazis. The importance of their roles cannot be overstated. One of the little known and short production types built by Miles was the Miles Monitor high-speed, twin-engine target tug. The prototype shown here being assessed at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at RAF Boscombe Down wears the “P” for Prototype roundel and yellow underbelly paint of an aircraft under evaluation. In the end, the RAF abandoned the type requirement and the Monitor was modified with dive brakes and other equipment to meet a possible Royal Navy requirement for an aircraft used to simulate dive bombing attacks on fleet ships. None entered service and the remaining aircraft were scrapped. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

Dumpy, utilitarian and oddly cheerful looking, the Miles M.57 Aerovan truly lived up to its name, looking much like a flying delivery van. First flown in early 1945, the type saw moderate success with 52 constructed. I selected this image because of two things—I was unfamiliar with the type and the cockpit in this image looks so sparse, it brought to mind the fake cockpits of movies of the period, where the normal complexities and equipment normally found in an interior of a cockpit are missing, replaced by what seems more like my parents’ wood paneled rec-room than an aircraft cockpit. The pilot seems to be sitting in an enclosed porch. The Miles Aerovan was made of plastic-bonded wood and was meant to serve the short-range, low cost transport sector. The only military operators of the type were the Israeli Air Force and Royal New Zealand Air Force. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

It’s all in the name. Another one of Miles Aircraft’s forays into the unknown was the Miles M.39N Libellula. I was attracted to the listing of the type in the 1000aircraftphotos.com alphabetical directory simply because I needed to know what a Libellula was and what it looked like. Turns out a libellula is a form of dragonfly whose twin sets of wings no doubt connected it to this tandem wing design (the forward wing or canard is visible but not obvious in the photograph) by Miles, normally a pretty conventional aircraft design company. The Miles M.39 was a five-eighths scale proof-of-concept prototype for a “lightly-armed, high-speed, high-altitude bomber”. Only one was constructed. Photo: Aubry Gratton Collection

The all-aluminum Monsted–Vincent MV-1 Starflight pusher airplane has the distinction of being the only four-engined aircraft ever to be built in Louisiana. It was to be an executive/business aircraft, designed by former Lockheed designer Art Turner “to give businessmen the same dependability and flying range that airlines give to their passengers.”* The only Starflight flew for the first time in October 1948. Despite having four engines, the Starflight could only carry 5 passengers and the pilot. It had a range of 1,200 miles at 145 mph—frankly, making it a terrible aircraft for businessmen who are looking for speedy travel. There was little taste for the aircraft and the only copy ended up at the Wedell Williams Memorial Aviation Museum in Patterson, Louisiana, USA, where, in 1992, it was heavily damaged by Hurricane Andrew. The wreck was moved to a storage hangar, where in 2005, it was destroyed by Hurricane Rita! * FLIGHT Magazine, January 1949. Photos: Dan Shumaker Collection

Students and researchers at Mississippi State University (Go Bulldogs!!) in Jackson built and flew the XV-11 Marvel in 1965 to test boundary layer and STOL technology. The name M.A.R.V.E.L. was a forced acronym that stood for “Mississippi Aerophysics Research Vehicle with Extended Latitude”. The first all-composite aircraft, it carried out its initial program of research on behalf of the US Army in the late 1960s, and was rebuilt in the 1980s as a proof-of-concept for a utility aircraft. The Marvel is now on permanent display at the Southern Museum of Flight at the Birmingham International Airport in Alabama. Photo: Jos Heyman Collection

I say it all the time—the Italians have style. The Savoia–Marchetti S.55 flying boat was one of the most beautiful and quirky flying machines of the 1920s, but the publicity stunt that vaulted it into world aviation history and even its lexicon was as impressive as its visual qualities and its substantial abilities in the air. The S.55 was a twin-hulled flying boat designed and built in Italy beginning in 1924. While passengers and cargo occupied the cavernous hulls, the cockpit crew flew the aircraft from the wing section between the hulls. The aircraft had prodigious long distance ability and to demonstrate this, Italian Air Marshal Italo Balbo led a full squadron of 24 identical S.55s across the Atlantic and to the Chicago World’s Fair (A Century of Progress Exposition) in 1933. The sight of 24 of the giants anchored on the Chicago waterfront captured the world’s imagination and inspired many a poster. The word “balbo” has come down the decades to mean a large gaggle of similar aircraft flying together in an aerial parade. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

Once again, I make my point about the Italian aircraft designers always being able to make their aircraft not just different, but beautiful... even when they are fat like this Savoia–Marshetti S.74 designed and constructed for the Italian airline Ala Littoria. Only three were built and they saw service from 1935. The aircraft shown here is the prototype, I-URBE, first flown in November of 1934. The S.74 could carry between 20 and 27 passengers in the lower compartment with astonishing panoramic windows, while the cockpit crew were five metres in the air. Navigator and radio man were seated in the enclosed nose. Photo: Dan Shumaker Collection

The Edgley E7A Optica—insectoid, quirky, and fascinating. “The Optica”, writes Johan Visschedijk of 1000aircraftphotos.com, “was a revolutionary design to obtain the best possible all around view that could be obtained by a fixed-wing aircraft. This would make the aircraft very useful in the fields of: police and frontier patrol; pipeline and power line inspection; forestry and coastal patrol; film, TV and press reporting; and touring. Despite its revolutionary design, it is a no-nonsense aircraft, simple and rugged.” Despite financial problems and corporate restructuring and sale, 22 copies of the type have been manufactured under various corporate entities since its first flight in 1979. For an excellent video of the type performing at an air show, click here. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

The Darmstadt D-22 was a cantilever sport biplane designed and built in Germany in the 1930s by the Akademische Fliegergruppe of Darmstadt University of Technology, a group of aerodynamical engineering students. The D-22 had quite an unorthodox configuration, being a cantilever biplane, with an upper wing placed low, just above the fuselage and ahead of its lower wing. The design emphasized aerodynamics and lightness and the aircraft was small (21.5 feet long with a wingspan of 24 feet—smaller than a Tiger Moth) with a streamlined silhouette. Two were constructed. Photo: Tracy Hancock Collection

Double dud. The Dassault M.D.410 Spirale was one of two nearly identical prototypes produced for the French Air Force—the M.D.410 Spirale and M.D.415 Communauté. The former was to be the ground-attack variant of the latter which was a liaison and general duty aircraft (training, command liaison and ambulance), with the latter’s windows removed and a glazed nose installed along with hardpoints and provisions for cannons. First flown in 1959, neither variant garnered any interest and the project was abandoned. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

It’s understandable if you thought this was an early model Boeing B737, but it is a Dassault Mercure, purpose-built to not just compete with the 737, but apparently to be its aviation doppelganger. Unfortunately, it was far from the success of the 737, the world’s most popular airliner (with nearly 9,000 produced). Only 12 Mercures were built—2 prototypes and 10 production aircraft, all purchased by Air Inter, at the time, France’s second largest airline. “This lack of interest was due to several factors, including the devaluation of the dollar and the oil crisis of the 1970s, but mainly because of the Mercure’s operating range—suitable for domestic European operations but unable to sustain longer routes. At maximum payload, the aircraft’s range was only 1,700 km. Consequently, the Mercure 100 achieved no foreign sales. With a total of only 10 sales with one of the prototypes refurbished and sold as the 11th Mercure to Air Inter, the airliner represented one of the worst failures of a commercial airliner in terms of aircraft sold.”—Wikipedia. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection

There is no more elegant engine configuration in all of aviation than a radial tri-motor. The Italians had their magnificent Savoia–Marchetti Sparvieros and Cant Alciones, and the French had the sleek pencil-thin Dewoitine D.338, a fast 22-passenger Air France liner of the late 1930s. Only 30 of the type were ever built (plus two one-off variants), but the aircraft had a reputation for reliability and good flying qualities. During the war, the Free French airline known as Lignes Aériennes Militaires flew the D.338 on scheduled service to Beirut and Brazzaville, French Congo. Nine of the aircraft survived the war and were put into service for a few months. Lufthansa, the German airline, made use of seven D.338s which they confiscated from Air France. For a French newsreel about the D.338, click here. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

The gear legs and wheel pants on the Bernard V.4, while no doubt extremely “draggy”, make this racing aircraft look very fast. The V.4 was actually a land adaptation of the Bernard H.V.120 seaplane racer (on pontoons, hence the very wide wheel stance) from Société des Avions Bernard. Two H.S.120s were built and one crashed and killed its pilot on its first flight (a common occurrence in those experimental days it seems). The remaining aircraft was put onto wheels and became the V.4. As fast as this aircraft looks, it in fact never flew. Photo: Nico Braas Collection

While there is nothing particularly fascinating about the Gloster S.S.35 Gnatsnapper, I include it here simply because its weird name made me laugh out loud—apparently a gnatsnapper is a British bird that catches gnats in flight. The Gnatsnapper, though designed by the famous Henry Folland, was a failed design—first flown in 1928. Only two prototypes were built as Gloster’s submission for an Air Ministry specification for a carrier-based aircraft. The winner of that competition was the Hawker Nimrod. The Gnatsnapper was part of a series of Gloster aircraft named after birds whose names started with the letter G and most of which were failures—Gamecock (108 built), Gannet (1 built), Gnatsnapper (2 built), Goldfinch (1 built), Grouse (1 built), Guan (2 built), Gorcock (3 built), and Grebe (133 built). Henry Folland, Gloster’s chief designer, would leave Gloster when it was taken over by Hawker in 1937 and start his own Folland Aircraft. His most successful aircraft design of all time, the Folland Gnat jet trainer (449 built) leads this author to believe he may have been the man behind the name Gnatsnapper. Photo: Bill Pippin Collection

No one designs aircraft with more style and panache than the Italians—witness the Piaggio P.23R. This three-engine monoplane transport was designed for no other purpose than to win speed records for Italy. Powered by three Isotta–Fraschini engines, the P.23R first flew in 1936. On 30 December 1938, it carried a payload of 5,000 kilograms at an average speed of 404 kilometres per hour, setting new world records over both the 1,000-kilometre and 2,000-kilometre distances. The P.23R’s development was halted in 1939. During the Second World War, however, Allied aircraft recognition manuals erroneously identified it as a possible Regia Aeronautica bomber. Photo: Ray Crupi Collection

The Wittman D.12 Bonzo was a spiffy little air racer built for the Thompson Trophy races in the 1930s. It was designed and built by Steve Wittman, whose name is now honoured at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Wittman Field in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Just 20 feet long and with a span of 20 feet (later 17 feet), the bright red Bonzo landed on two of the tiniest pneumatic aircraft tires imaginable—an attempt to reduce drag. Fully restored, it now graces the EAA AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh. Sylvester Joseph “Steve” Wittman (5 April 1904–27 April 1995), competed in and won more air races than anyone else between 1926 and 1989, therefore he is also referred to as the “Dean of American Racing Pilots” writes 1000aircraftphotos.com. Photo: Ray Crupi Collection

![Armstrong Whitworth’s third airliner type, the Ensign, was the largest machine built in pre-war days for Imperial Airways Ltd. and, like [its predecessor] the Atalanta, was a four-engine high-wing cantilever monoplane designed by John Lloyd. There the similarity ended, the newcomer being of almost twice the physical size, three times the all-up weight, of all-metal stressed skin construction, and fitted with an enormous retractable undercarriage. Power plants were four 850 hp Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX engines. It carried 27 passengers in three cabins and was intended for the distant Empire routes, sleeping accommodation being alternatively provided for 20. One promotional newsreel of 1937 stated that the Ensign was “a new streamline monster in the Empire skyways”. For another period newsreel about the Ensign, click here. Photo: Alfarrabista Collection](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1629300477683-F837G8XFTEWD33OMBG7I/1000AP10.jpeg)

![Many of the rare aircraft types listed in the pages of 1000aircraftphotos.com were never meant for production. Many, like this Hunting H.126, were simply designed and built to test a new concept, principle or technology. Hunting Aircraft’s H.126 was “a single-seat research aircraft which had been built to flight test the jet-flap principle [widely called “blown flaps” today]. In this, the exhaust efflux of a turbojet engine is ducted to the trailing edge of an aircraft’s wings and ejected through a narrow slit along the trailing edge. As well as being used to provide propulsion, the efflux can be deflected downward to form a “jet-flap” of high velocity gas which makes possible the achievement of lift coefficients of 10 or more.” The aircraft was designed purely for test purposes and thus lacked features such as retractable landing gear. The shoulder-level wing featured a set of struts, not for support but in order to provide piping for the compressed air used in the blown flaps. The sole H.126 flew for the first time on 26 March 1963, and had completed over 100 test flights by mid-1965 with the program ending in 1967. After two years storage it went to NASA in the USA in 1969, returning in May 1970. Stored for another two years it was struck off charge in September 1972 and is presently on display at the RAF Museum, Cosford. Photo: Johan Visschedijk Collection](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1629300632236-OWNXMHXCDXGC57DGMOC8/1000AP11.jpeg)

![The Handley Page H.P.75 is the type of airplane one might see in an Indiana Jones movie—one that breaks all the control configuration paradigms at once. Johan Visschedijk elaborates on the type. First known as the “Tailless Research Aircraft” [hence the name Manx—the tailless cat -Ed] this aircraft was designed by Dr. Gustav Victor Lachmann to investigate the problems associated with tailless aircraft. The airframe was built by Dart Aircraft of Dunstable, England; the aircraft was finished at Radlett, England. During taxi trials on 12 September 1942, the aircraft flew unintentionally at a height of 12 ft (3.66 m) and was subsequently damaged while landing. Marked with the ‘Class B’ markings* H-0222, the aircraft flew for the first time on 25 June 1943. In 1945 it was designated H.P.75 for the first time. A total of 31 flights were made till 3 April 1946 (total flight time 17 hr 43 min) when the aircraft was stored and subsequently scrapped in 1952. * British aircraft test serials (in this case HO222) are used to externally identify aircraft flown within the United Kingdom without a full Certificate of Airworthiness. They can be used for testing experimental aircraft or modifications, pre-delivery flights for foreign customers and are sometimes referred to as “B” class markings. Photos: Bernhard C. F. Klein Collection](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1629300926014-7MC3QAQM4SXK59MO3NOD/1000AP19.jpeg)