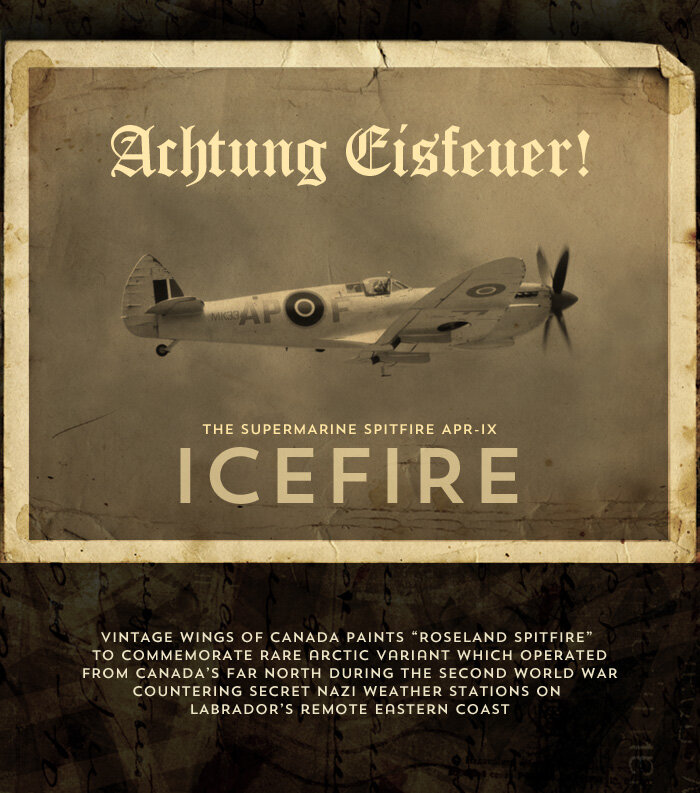

Achtung Eisfeuer!! — The Supermarine Spitfire APR-IX

First Published April 1st, 2012 April Fool’s

Vintage Wings of Canada is proud to announce that, as the restoration of Spitfire TE294 nears completion, it will no longer be painted to resemble 442 Squadron Spitfire Y2-K as originally planned. Instead, this historic restoration will be painted in a Spitfire paint scheme wholly unique to Canada—the Polar White Arctic camouflage used by 14 Squadron, RCAF on Arctic coastal defence during the Second World War. It will still be known as The Roseland Spitfire, honouring Flight Lieutenant Arnold Roseland, but, in this rare scheme, will pay tribute to the largely unheralded squadrons of the Home War Effort. While the Spitfire will be a standard Mk IX, this paint scheme will now pay homage to the rare Spitfire APR-IX, a mark used only in Canada.

The latest from the paint booth at Vintage Wings

The Back Story

A weary Kapitänleutnant Clemens von Mannheim-Dampfwalze was anxious, very anxious. He had been working his U-537 down the bleak northernmost coast of Labrador for several days, slinking in and out of bays on the surface, hiding by day, relying on the remote location and bad weather to keep away any unwanted and prying eyes. Now, in the last week of October, he needed just this day to finish his task and take his U-boat and his crew back home.

Just six days before, the handsome 26-year-old von Mannheim-Dampfwalze had conned his diesel electric submarine on the surface into remote Ikkudliayuk Fiord, threading between Home, Avayalik and Oo-Olilik Islands to drop anchor. Here, in the protected expanse of Martin Bay, the crew, along with three technicians from Siemens, off-loaded 10 strange camouflaged metal canisters about one metre in height and half a metre in diameter. The drum-like canisters contained sophisticated and delicate weather instruments and nickel-cadmium batteries meant to power a clandestine and autonomous weather station known as a Wetter-Funkgerät Land (WFL). It took the technicians two whole days to get the weather station set and powered up. The whole time, von Mannheim-Dampfwalze anxiously waited in his conning tower, or leaning over the rail on the “winter garden” watching the entry to Martin Bay. He had been near Cape Chidley, the northernmost point of Labrador, hundreds of miles from any significant human habitation and in a spot where humans rarely visited, let alone patrolling ships or Coastal Command aircraft, yet von Mannheim-Dampfwalze was not comfortable being on the surface. He had longed to finish his task and get the hell out of there.

Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze’s U-537 photographed by a Siemens technician at Martin Bay, Labrador on 22 October 1943. The location was not far from Cape Chidley, the northernmost point on the Labrador coast. After dropping anchor in the bay, the Siemens technicians responsible had off-loaded the canisters, while crew members scouted ahead for a suitable location to set off the weather station. Photo: Bundesarchiv

U-537 anchored in secluded Martin Bay, Labrador in pale winter sunlight on the morning of 22 October 1943. This shot was taken from the bluff where the weather station was being set up. The crew and the three Siemens technicians, led by Kurt Sommermeyer, took just 36 hours to offload and install the weather station high on the windswept plain. While they waited for the weather station installation to be completed, his crew managed to repair extensive damage caused to his submarine en route by a rogue wave during a North Atlantic storm. This included damage to his hull and an inoperable quad-flak gun. Unable to submerge and defenceless against aircraft, von Mannheim-Dampfwalze was understandably edgy. When the installation was finished, it was christened Weather Station Kurt. By the time they had left Martin Bay, the weather had worsened, with low cloud, snow squalls and decreased temperature. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Related Stories

Click on image

Two incidents at Martin Bay had set him on edge. In the afternoon, a shot rang out in the bay, echoing back and forth across the water. Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze had called for an immediate action stations and glassed the installation team high on the hillside to the north. He could make out Oberbootsmann Martin Strasser, the U-boat’s bosun, waving madly from the heights, but without radio communications, it was two hours before the captain had understood what had happened. The team had been surprised by a polar bear and Strasser had shot it dead at close range with a rifle. The bear was brought aboard the U-boat and cleaned, causing even greater delay. Then, near the end of that day, just as they were getting ready to weigh anchor, von Mannheim-Dampfwalze thought for a brief haunting moment of dread, that he heard the distant snarl of an aircraft engine. The cloud had, by that time, driven low into the fiord and the sound had only been fleeting. There could be no way that an aircraft of any sort could have been this far north or this far from the known U-boat hunting grounds. He had been sure of it, but still, a bad feeling had begun to creep into his mind like the approaching bad weather. He had thought to himself, “It’s time to leave this forsaken spot”.

U-537’s bosun, Oberbootsmann Martin Strasser (centre) beams with pride on the afterdeck of the submarine as he poses with other crew members and the polar bear he shot near the weather station installation. Behind him in the “winter garden”, von Mannheim-Dampfwalze waits impatiently for the bear to be cleaned and for his boat to be underway. By 1735 hrs, the U-boat slipped its way past Oo-Olilik Island, turned south east and worked its way out to deeper water to test the repair to its hull. Miles behind them, Weather Station Kurt began beaming information across the Atlantic—warning of a weather system that would bring bad flying weather for the next six days—just the kind of data U-boat operational planners had wanted since the beginning of the war.

That was a nearly a week ago, and the bad feeling had not left him. His original orders were to deliver just the single weather station and then to resume a standard offensive patrol as part of Wolfpack Amadeus. Another boat, U-867, was to deliver the first of two weather stations on Labrador’s coast, but it had been sunk by a Coastal Command B-24 Liberator en route. Before he left the pens at Lorient, France, the equipment for a second complete station (WFL-27) was loaded aboard. To make room for the two sets of canisters, two of his precious “fish” (torpedoes) were left behind.

While quietly working his way south to Bytabadliuk Island, reluctant to submerge in a region that was so poorly charted, he received a coded Enigma message that there was a change of plans. He was no longer going to Bytabadliuk, instead a slender bay cutting deep into vertical cliffs and rocky promontories between Kikkertavak and Tunungayualok Islands two hundred kilometres to the south. In the bay, they were to set up the second WFL site on a small island called Kiuvik. To get there, von Mannhein-Dampfwalze had had to manoeuvre his boat slowly in sleet and rain past shoals and hidden rocks. He could only do this by day, and even then, the weather was miserable with visibility only a couple of miles. He arrived there on 28 October at 0835 hrs. Screened from the open sea by numerous outer islands and devoid of anything but rock, the expanse of water seemed the perfect spot, yet von Mannheim-Dampfwalze had a bad feeling. He did not like a change of plans.

There are only two known photographs of U-537 at Kiuvik Island. In this shot, an away team from U-537, searching for a suitable site (away from prying eyes of Inuit hunters, protected from the sea, but open enough to record relevant wind speeds, barometric pressures, temperatures and precipitation), stands on a knoll on shore on Kiuvik, more than 200 kilometres southeast of the Leutonian settlement at Hebron and 100 kilometres from the Hudson Bay Company depot at Okak. Aboard the boat, crews scramble to launch inflatable boats to carry the equipment to shore. Clemens von Mannheim-Dampfwalze eyed the oncoming better weather with distrust. For the past week, scuttling down the coast from Martin Bay and looking for the spot to set up the second installation WFL-27, they had encountered sleet, freezing rain, snow and the kind of weather any U-boat captain loves when he is on the surface. Photo: Bundesarchiv

This photograph, reportedly taken by von Mannheim-Dampfwalze himself, shows the scene on the aft deck of U-537 as the crew and Siemens technicians struggle to launch three rafts into which they placed the canisters and associated equipment for WFL-27. Moments later, all hell broke loose. Photo: Bundesarchiv

By 0930 hrs, he had dispatched a scouting party to shore and began bringing three large inflatable rafts and the weather station up from below through the torpedo loading door in the aft deck. Immediately things began to go wrong. The compressed air hose used to inflate the rafts split under pressure. It took one of his maschinisten half an hour to repair the damage. As the first two rafts were inflated, it was obvious that one had a major leak. As the weather station canisters were loaded aboard the one good raft, which had been lowered over the side, the crew scrambled to inflate the third. They would have to do it with just two rafts. There were three men in the raft with the weather gear, and seven men on the after deck. The bosun, Strasser, was standing at the winter garden railing, cursing at Electro Obermaschinist Uwe Kock.

Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze was on the conning tower, with his back to the No. 1 periscope. He had his Zeiss binoculars in his hands, and had been looking out toward the entrance of the bay. But he wasn’t looking at anything in particular. Instead, he had his head cocked to one side, like a dog trying to understand what he was hearing. The crew was clattering about the deck, wrenches clanging, hoses hissing, men cursing. The captain cocked his head the other way, then bellowed at the top of his lungs “Stille, du verdammter idioten!”

As the crew struggled to turn off the compressed air, the U-boat became silent except for the lapping of black water along her sides and the thrum of her diesels. Blue smoke rose on the wet air from her open exhaust valves. The bay lay quiet under the thin snow. Everyone looked at von Mannheim-Dampfwalze. Only a few flakes of wet snow were falling. Breaks could be seen in the solid grey mass of the cloud. The sun brightened the snow on distant mountains.

All eyes were on their captain and no one was looking to the north, except him. But they all could hear it now—the faint, yet distinctive, snarl of an aircraft engine, maybe more than one. Down on the water, surrounded by rocky outcrops and high bluffs, no one could say for sure where the sound was coming from. No one spoke. Heads turned in all directions. Then the Captain, pointied to the north, screamed “ALARM…FLUGZEUG!!!!”

The crew was so completely stunned by the appearance of two fighter aircraft, they might as well have been alien spaceships. It took several seconds for them to react, and as the crew scrambled to get off the deck and to the quad-flak gun, a fast moving pair of dark silhouetted fighter aircraft low on the horizon and on a southerly heading that would have taken them to the west of the bay, suddenly banked left and carved a long smooth arc that brought them head-on to the grey hulk of U-537. Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze stayed on deck and stood his ground, but was unable to comprehend what he was seeing. Spitfires! This is not possible!

The two Spitfires seemed to drop down onto the surface of the bay, one behind the other. The first opened up about half a kilometre away. They could see the blue smoke coming from the cannons, bright flashes from the machine guns outboard of the cannons and the glitter of brass cascading in the weak sunlight that now spread across the bay. Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze would survive the war, and the image of these two Spitfires bearing down on him over the icy black waters and snow dusted cliffs would be one that woke him in a cold sweat until his dying days.

In an instant, great gouts of white spray exploded upwards from the black water, pounding towards the stern of U-537. Two of the men in the raft jumped to the submarine’s external ballast tank and scrambled onto the after deck, while the third leapt into the water. The cannon rounds struck the deck with explosive shrieks, sparks flying, and duck boarding exploding into match sticks. Several rounds struck the conning tower, one penetrating the coaming and blasting the radio compass loop from its mount. Seconds later, the two Spitfires roared overhead, thundering past, pale sun glinting on white wings. Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze did not flinch. Two thoughts passed through his mind simultaneously. Those Spitfires were white and where the hell could they have come from? Spitfires could not possibly fly over such inhospitable and remote territory. They had a single engine, short range and most importantly... no bases. It was impossible. Four-engined Condors or those bastard Liberators, this might be possible, but Spitfires?? But here they were, bearing down on him and his boat—and him caught in the open with absolutely nowhere to go

Below him, his gunners scrambled to tear the covers from the muzzles of the quad 20 mm Flakvierling 38. Curses rose from the deck as sailors tried desperately to tie off the raft, which had been holed on several places. Several of the nickel-cadmium battery canisters were smoking, and one was burning fiercely. Strasser threw a line to the sailor in the water as the weight of the WFL began to sink the raft. Air hissed and popped from the holed rafts. On shore, as the Spits arced round again, he could hear the away team blasting ineffectively with a Schmeisser MP-40 submachine gun and even a hunting rifle. As the Spitfires continued in a tight left bank, their all-white forms stood sharply against the dark cloud on the horizon, with the low, weak sun burnishing their slender backs with light.

While the two white Spitfires climbed in the turn for altitude, von Mannheim-Dampfwalze barked out a series of orders—to haul up the anchor, get ready to submerge on the spot if the attack continued, and load the quad flak gun. Men shouted, some who were wounded swore at their pain as they were helped below. Strasser leaped from the winter garden, made his way aft cutting loose the two ruined rafts, and shutting the torpedo loading hatch from the outside.

At length, the two Spitfires were lined up again, this time abeam the U-boat, and about two kilometres to the north. “Kannonen bereit, nicht aber zu scheiben, sie warten... warten... gerund.” He called out, settling his men down, exhorting them to patience... wait, wait. He alternated between shouting at the men on the gun deck and down between his legs through the tower hatch to the watch crew below.

The moment the bow anchor lifted from the bottom, he called for full speed and full left rudder, hoping to swing the boat bow-on to the coming maelstrom. It was far too late.

Moments later, there were flashes again on the wings of the Spitfires and a second later white slashes of cannon fire walked across the water with such violence and speed that von Mannheim-Dampfwalze finally flinched and ducked behind the coaming. Several rounds of cannon fire slammed into the side of the submarine. The noise was appalling, like heavy sledges slamming into a steel wall, followed by a shriek, a heavy metallic ringing and a hot ripping sound. Over top of this, he heard the bellowing of his gun crew, the high speed explosive thump of the quad 20s and the ringing of brass casings ejecting from the breaches. The men were well trained and could load four magazines of 20 heavy shells each, every ten seconds. They had time only for 10 seconds before the two fighters flashed over them.

By this time the U-boat, with its diesels thundering aft, was swinging around to the north, but von Mannheim-Dampfwalze kept his eye on the two Spitfires while thundering orders at the same time. Alarm!!! Fluten!! Alarm bells rang throughout the boat. He knew that if he could submerge right here, the cannon fire from the white fighters would not harm him. The gun crew scrambled down the deck hatch as explosive sprays of compressed air blasted from the ballast tanks. As U-537 began to submerge, the swinging of the boat was stopped and the engines brought to “Stop”. Moments later, the black cold water swept over the decks and swirled around the conning tower. The U-boat settled, bow down and slipped beneath the dangerous waters

Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze brought her down to 50 feet and settled, waiting, worrying about his men on the shore, angry that he had lost the WFL, and still astonished at what had just happened. With his men, he stared at the bulkhead, as if he could see through the pressure hull and 50 feet of water to those evil white bellies of the Spitfires.

He knew that the Spitfires had little loitering time, but he waited a silent and frustrating hour anyway. At least the pressure hull was intact. Coming to periscope depth, he scanned the horizon and saw nothing of the two fighters, but the three men from the away team were in the raft and only 50 metres away… waving madly at the scope. Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze smiled, grateful they were not hurt. He surfaced the boat, collected his men and made ready to leave on the surface, anxious to get to deep, safe and open water. As U-573 moved out of the bay, the captain scanned the water and noted that one of the rafts was still floating, too far to retrieve. Ten minutes later U-537 slid out of the bay and made haste for the deep, licking her wounds.

Von Mannheim-Dampfwalze had just experienced the first, and as it turned out, the only known combat action by the Royal Canadian Air Force’s Supermarine Spitfire APR-IX, Arctic patrol fighter. Little is heard or understood today of the Spitfire APR-IXs which were operated by the five remote detachments of 14 Squadron, RCAF along one of the world’s most isolated and inhospitable coastlines—the east coast of Labrador, then part of the Dominion of Newfoundland. Some say it was a misconceived idea, but at the time, Canadian and American military planners considered it of immediate importance (as we will learn) to deploy a mobile military presence in the eastern arctic region spanning from Hudson Strait southward to Goose Bay, Labrador. This isolated stretch of coastline was 800 miles of craggy islands, massive sea cliffs, wind blasted heights, and deep fiords. Along its length were scattered few communities. Since many of the native Inuit people of the region had lived from the land as nomads, there were few permanent communities, but there existed a religious archipelago of isolated Christian missions that clung to some of the remotest and forbidding locations on earth—tiny weather-beaten wooden villages with names like Hebron, Hoffnungsthal (Hopedale), Okak, Zoar, Ramah, Makkovik and Killinek. These were run by a peculiar sect of European missionaries of Leutonian descent known derisively on mainland Newfoundland as the “Holy Cabbage Rollers”.

Very little, if anything, can be found on the internet today relating to APR-IX operations in the arctic. Much of what the author was able to find came from the family of Squadron Leader Stéphane Gelécul, the first and only commanding officer of a Canadian Spitfire squadron operating in Canada or Newfoundland during the Second World War. His logbook and photographs, cherished today by his grand nephew Sébastien Bouffard, enabled us to piece together this long forgotten story of a uniquely Canadian experience with the Supermarine Spitfire. Gelécul and his wingman, Pilot Officer E. Falkingham, were the two pilots who caught von Mannheim-Dampfwalze’s U-537 in the open water at Kikkertavak. A brief note in Gelécul’s logbook—“Sunk U-sub [sic] off Kikkertavak. Two passes, with Falky.”—clearly shows that he felt he had sunk the submarine. The next day, when a Canso from Goose Bay circled the spot, nothing could be found. A ship (HMCS Howard Morenz) was also dispatched, but found nothing but two rafts, holed and washed ashore along with wood duckboard fragments. RCAF intelligence officers rightly overturned Gelécul’s claim to have sunk the U-boat.

The Leutonian Menace

Since the mid-18th century, protestant Episcopalian missionaries from the mountainous Leutonian region of the Sudetenland had built small isolated communities up the Labradorian coast, in places so remote, only one supply ship would reach them each year. These were centred around a communal living building and church. It was the Leutonian missionaries’ dream to convert the local Inuit population to Christianity and build a utopian world where Leutonian Episcopalians could practice their traditions without being persecuted. At first there was great resistance from the Inuit, with entire Leutonian missions being attacked and wiped out. Slowly, however, the Leutonians won over the local subsistence population with cabbage rolls, coffee and religious accordion music. Some of these communities, like Okak and Hebron, had flourished for many decades and then collapsed after the flu pandemic of 1917–18. By the time that the Second World War had broken out, the Inuit and Leutonian peoples had established a relatively peaceful relationship, far from authority and the control of the Newfoundland government... and that was a problem.

Many are aware of the rough treatment that was meted out to Canadians of Japanese descent during the Second World War. Forced from their homes and businesses, they were rounded up and moved inland away from the west coast to concentration camps where they were kept until the end of the war. Such was the paranoia of the day. For two years before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the isolated Leutonian communities of Labrador were viewed with much the same mistrust, for, though they spoke a rare Leutonian mountain dialect, they were from a predominantly German-speaking region of the Sudetenland—a place where they had been welcomed after being driven from their native Leutonia, a now long-forgotten region of the Polish interior. The Leutonians were led west to Sudetenland from their cultural ancestral homelands in Poland in 1268 by the legendary Schmenge, or tribal leader, the great Yosh the Elder. Grateful to the Teutonic and Saxon peoples who had succoured them, the Leutonians were pro-German by nature.

Yosh, the Elder, the great Leutonian Schmenge (literally “One who gives Coffee”) who led the Leutonian exodus to what was, in 1939, German-speaking Sudetenland. Such was his impact on the lives and futures of the Leutonian people, that half of all Leutonian families have the last name Schmenge. The classic Leutonian folksong “Falutniks and a Homeland” pays musical tribute to his impact. Photo: Leutonian Legacy Project

It was suspected that the Leutonian missionaries still harboured sympathies for the Germans and some believed that Nazi agents and saboteurs were filtering into North America through the mission supply ships. There was also a suspicion that the Leutonians were radioing weather information to submarines far out in the North Atlantic, and that they were even supplying some U-boats with fresh food and supplies. At the outset of the war, people in the south called for rounding them up (as Canada would later do to the Japanese) and isolating them—but since they were already isolated, it was decided to leave them alone, but set up a series of air bases along the coast, from which coastal patrols could “keep an eye on them”.

Operation Icefire and the Spitfire APR-IX.

There was, at that time a large number of RCAF fighter and patrol bomber squadrons actively employed in the defence of both the west and east coasts of Canada and Newfoundland. The fighter squadrons operated Canadian-built Hawker Hurricane XIIs and P-40 Kittyhawks, but there was a strong movement among RCAF leadership (particularly pilots) to bring the more capable Supermarine Spitfire to participate in Canada’s defence.

For the first three years of the war, Spitfires were in short supply and in great demand in England. But, as the Nazis were now clearly confined within continental Europe and with increased production, Fighter Command of the Royal Air Force allowed the release and shipping of 24 factory fresh Spitfire Mk IXs to Canada for an operational experiment known as Operation Icefire.

Icefire’s strategists had an ambitious, some say overly-complex and expensive, plan to build a series of temporary airfields up the length of the Labrador coast all the way to Killinik Island in the Northwest Territories. Each would be no more than 300 miles from the next, so that the short-ranged Spitfires could work their way along the coast with aerodromes well within their range. The RCAF brass planned on utilizing airfields cleared for the exploratory Hudson Strait Expedition of 1927–28, ice runways when the temperatures allowed and newly constructed airfields close to the Leutonian mission settlements along the coast of Labrador. Construction and engineering units were despatched to sites along the Labradorian coast at Zoar, Ramah, Makkovik and Hopedale and in Hudson Strait at Port Burwell. Already there was a large base of operations at Goose Bay supporting the transatlantic delivery of multi-engine aircraft to the European war. This was to be the repair and service depot for 14 Squadron’s Spitfire APRs and the southernmost of the detachments of the unit. Of the 24 Spitfires that arrived at Halifax on 12 July 1943, six were held in storage at RCAF Station Dartmouth (today’s Shearwater), and 18 were shipped by coastal supply steamer to Goose Bay for conversion to APR standard. When the all-white Spitfires were rolled out at Goose Bay, operational staff and pilots took to calling them by several names—Icefires, APRs, APR-IXs or Snowbats. Later, after several months of operations, they also became known by the Inuit word, Ookpik.

Operation Icefire was officially commenced in the Spring of 1943 (following breakup of coastal icefields) with the arrival of barges, construction crews and administrative staff at all five sites selected for Icefire bases—Hopedale, Makkovik, Hebron, Zoar and Port Burwell (Killinik). Throughout the summer months, engineers, surveyors and carpenters laboured through one of the warmest Arctic summers on record, battling black flies, mosquitoes, boredom and loneliness. By August of that year, airstrips had been graded and prepared for Hudson and Dakota transport aircraft bringing in more equipment and more people. In early September, at Zoar, Hopedale and Port Burwell, steamships arrived towing massive “base barges”—200 foot long floating airbases with fuel and oil storage enough for a full winter’s operation. These were sunk to the bottom in the shallow waters, there to await freeze-up and the formation of an ice-port or as the men called them icedromes.

A Fokker Universal of the Hudson Strait Expedition of 1927–28. This team of 41 men, including members of the RCAF, Army, RCMP and civilian life, was tasked with setting up bases on Hudson Strait from which to operate the six Fokkers and single de Havilland Moth of the expedition in search of data of ice movement in the strait. Three bases were established along the length of the strait from which the Fokker aircraft were flown. The southernmost of these bases, near the entrance to the strait, was Port Burwell, an old Dominion meteorological station first established in 1884. The airfield and facilities built here by the Hudson Strait Expedition would form the basis of Operation Icefire’s northernmost reach. When the Spitfire APR-IXs first arrived by ship in the summer of 1943, they were assembled in the old hangars built to house the Fokker Universals. The local population had, to this point, only ever seen the boxy Fokkers, so when the predacious-looking Spits arrived, the Inuit took to calling them “Ookpiks” after the largest aerial predator in the region—the mystical Snowy Owl. Photo: RCAF

A Fokker Universal of the Hudson Strait Expedition is serviced in a purpose-built hangar at Port Burwell, Northwest Territories in 1928. Fifteen years later, these same hangars were used by the RCAF to assemble two Spitfire APR-IXs, while the airfield, which had been first cleared for the Universals, was lengthened to handle Spitfires. The Spits arrived aboard SS Taberhuit, a Newfoundland coastal supply ship towing a 200 foot self-propelled barge. The barge itself was a mobile air base, containing sleeping and messing accommodations for the 36 men of the 14 Squadron Burwell Detachment as well as workshops and more than 60,000 gallons of high octane fuel and 6,000 gallons of oil in onboard bunkers. It was designed to be beached and frozen into the ice off Burwell and to provide all the comforts of a southern base. There was even a small cinema on board. Photo: RCAF

The hangar and facilities at Zoar in December of 1943. The winter of 1943–44 was particularly harsh, wreaking havoc not only on flying operations with the APRs, but causing continuous mechanical problems for the Spits—with frozen oil lines, frozen tires, Perspex literally shattering in the minus 75 F temperatures, fabric surfaces splitting and many other woes. Photo: RCAF

The Supermarine Spitfire APR-IX “Icefire”

The pilots of the APR-IX were specifically selected from the ranks of other Home War Effort fighter squadrons for both their flying AND their survival skills. Operating single engine aircraft in such a remote setting came with some obvious dangers—inclement and fast moving weather systems, rough and mountainous terrain and utter isolation. Planners looked for pilots who had some experience living off the land and hunting. If forced to bail out over this type of terrain, an Icefire pilot could expect that rescue was unlikely. Instead, it was expected that downed pilots should immediately begin to find their own way to the nearest Leutonian mission, Hudson Bay post or Inuit encampment and from there, back to their units. APR Spitfires were modified to include an extensive survival kit, weapons and supplies for two weeks for a single airman. Before reporting for duty, those recruited to becomeIcefire pilots, all of whom were volunteers, went through a rigorous three-month winter survival course in 1942 at Churchill, Manitoba on the coast of Hudson Bay. It was so rigorous, that 25% of the men who attempted the course quit before it was over and returned to their squadrons.

The Icefire was not a true mark of the legendary fighter, but there were enough modifications and specialized equipment added that the RCAF gave it its own designation—the Arctic Patrol and Reconnaissance (APR) IX. There were linkages for two underwing drop tanks of the type employed by the P-51 Mustang, better defrosting and heating in the cockpit, lightweight snow chains on the tires to counter the effects of crosswind on ice, and the APR’s Merlin had an electric immersion heater in its oil pan. The largest modification was the addition of a large survival kit bay in the rear fuselage. On the starboard side, aft of the roundel, a hinged access panel 28 inches wide and 13. 5 inches high was added to give increased access to two separate compartments between frames 16, 17 and 18. In one case local technology was used to increase engine temperature—perforated sealskin panels covered the intakes of both radiator boats on some of the APRs. These reduced the flow of cooling air, in the same way trucks in Canada have fabric covers over their grills in winter.

During the nine months of Icefire, six APRs were lost. Two (AP-A and AP-G) were destroyed at Port Burwell in separate incidents when their oil pan immersion heaters ignited a fire. One Spitfire APR (AP-D) was lost at Zoar when it landed long and ran off the ice runway and into the Atlantic (its pilot Flight Sergeant Elvin “Puddles” Arsenault managed to extricate himself and was rescued). Two APRs (AP-H and AP-Q) were destroyed in a hangar fire at Makkovik in December when a space heater caught fire and finally, as the aircraft were being flown back to Dartmouth at the end of Icefire, one last aircraft was lost along with its pilot, Flying Officer Trevor “Glammo” Bassfinder (the only casualty of Icefire). After the end of Operation Icefire (some say failure) in May 1944, the remaining 18 Spitfires were shipped back to England, some of which arrived in time to participate in flying operations with RCAF squadrons in Normandy. One of those APRs was MK304, the very same aircraft pictured in the famous Y2-K engine change photo. This is the aircraft which we were going to paint in its 442 Squadron markings, but now that we have learned that Arnold Roseland had never flown it, we will instead be honouring 14 Squadron’s Spitfire APR-IXs of Operation Icefire

The Icefire experience was largely deemed a failure by the Royal Canadian Air Force and the McKenzie King government of Canada. The cost overruns for airfield preparation and staffing were staggering—$2.5 billion in today’s dollars! Of the 24 Spitfires shipped from the Castle Bromwich Supermarine factory in England, 20 (original 18 plus 2 replacements) achieved ARP operational status with four still in crates in Dartmouth at the end. Five were lost in accidents and one on the last flight to Dartmouth. One pilot was killed. The only action recorded was Gelécul and Falkingham’s attack on U-573. In hindsight, we now know that their presence in the north did in fact prevent more U-boats delivering automatic weather stations to the Labrador and Canadian Arctic coasts. The fear of Leutonian spies and agents, however, was completely unfounded. There is no evidence to support any seditious activity on the part of the missionaries. The project was largely forgotten and many of its records and files destroyed to minimize postwar political fallout.

Today, very little evidence exists of Operation Icefire, its pilots, ground crews and aircraft, but Vintage Wings of Canada’s all-white tribute to the Supermarine Spitfire APR-IXs of 14 Squadron will now tell a great Canadian story where previously there was none.

Supermarine Spitfire IX, MK304, in 442 Squadron markings gets an engine change in the field in August of 1944. Just six months before, MK304 was flying coastal defence sorties in Labrador with 14 Squadron. A close look at this Spitfire reveals that the topside of the port wing still carries its all-white Arctic camouflage. Photo: RCAF

A colour profile of Supermarine Spitfire IX MK334 as AP-K, a 14 Squadron RCAF Icefire. The aircraft was painted overall white with squadron codes painted in Ocean Grey and the spinner in Azure Blue. The blue spinner was reportedly chosen by an RCAF fitter at Goose Bay who hailed from Nova Scotia, where locals refer to themselves as Bluenosers. Profile by Evad Yellamo

A close-up of the centre section of MK334’s fuselage shows details of the simple artwork that adorned Squadron Leader Stéphane Gelécul’s Icefire (Gelécul was the 14 Squadron commander). The Anglicised sobriquet Ookpik and a stylized cartoon of a Snowy Owl figure were painted in Ocean Grey forward of the cockpit door. Having spent more than three months at the northernmost Operation Icefire station at Port Burwell, Northwest Territories (today’s Nunavut), Gelécul had much exposure to local culture and legend. The Inuit population had little experience with aircraft in the very far north. In fact, only a few had ever come their way. The first exposure to mechanical flight at Port Burwell had come in the form of slab-sided Fokker Universals during the 1927–28 Hudson Strait Expedition to study ice movement. Though the earlier 1919 Labrador expedition had prepared a landing strip at Nain, this was just halfway up the Labradorian coast. The sight of the sleek and powerful Spitfires painted white was far from their norm and, at first, frightened the local population, and then captured their creative imaginations. Being told that the Spitfires were used to hunt the enemy, the Inuit made the obvious comparison to the one all-white flying predator they were familiar with—Ookpik—the Inuktitut word for what southerners call the Snowy Owl. There remains very little photographic evidence of Spitfire MK334, but there is a sketch and description of the artwork in Gelécul’s logbook, which is kept at the Library and Archives Canada facility in Gatineau, Québec. Profile by Evad Yellamo

There are no photographs to be found on the internet of APR Spits in operation in the north. This detail from a photograph in Squadron Leader Gelécul’s logbook is perhaps the best known view of a 14 Squadron Spitfire APR-IX flying. It shows MK334 in its later code as AP-F for Freddie. After MK367 (AP-F) was sent for repairs to Goose Bay after a landing accident at Zoar in March of 1944, MK334 was reassigned to that detachment and re-coded AP-F. The handwritten note on the back reads “My old kite – flown by “Glammo”. Flying Officer Trevor “Glammo” Bassfinder, a 14 Squadron pilot of the Zoar detachment was lost and presumed killed when his Spitfire APR failed to land after the squadron was sent south en masse for disbandment at Dartmouth. Photo: Flight Sergeant Simon Hodson, RCAF Photo Unit

Another damaged print from Gelécul’s logbook shows a 14 Squadron Spitfire APR-IX (AP-R) thundering low in a turn over Killinik Island. The note on the reverse side says “My Air Demo for Locals! - 4/10/43”. Photo: Gelécul family archive

A photo from Gelécul’s logbook shows a pair of RCAF Spitfire APR-IXs (AP-A and AP-H) executing a tight formation flypast at Hopedale, Labrador. Gelécul’s caption on the back of the photo reads: “Me leading do at Hopedale - Sep. 43”. Gelécul’s logbook indicates that he was in Hopedale in September of 1943 for a disciplinary matter involving a pilot by the name of F/S Morris Richard, who had punched unconscious another 14 Squadron member during a game of shinny. This photograph is unique in that both of the Icefires depicted were written off during Operation Icefire—AP-H after a hangar fire in Makkovik, two months later and AP-A at Port Burwell when the immersion heater modification malfunctioned and caused a fire which destroyed the aircraft. Photo: Gelécul family archive

A Spitfire IX of the Royal Canadian Air Force (one of the 18 converted to APR-IX standard) is photographed at Wright Field, Ohio, where it was flown to be tested with American-style drop tanks. The tests were successful and the modifications were made to the entire squadron at Goose Bay. Photo: RCAF

Spitfire APR-IX (AP-D, RAF serial No. MK366—lost at the Zoar detachment in February 1944) taxies on the ice runway at Makkovik’s Tilt Cove in late November 1943. The ice runways, like the open grass fields of England, allowed aircraft to take off and land directly in the wind. This wouldn’t be possible on the sea ice which was susceptible to movement and ridging. In the protected coves cut deep into the mainland, the ice was as steady as an Ontario lake and frozen to 14 feet or more in the depth of a Labradorian winter. The Makkovik construction crews also built a runway on the land to the south of the community which is still in use today. Photo: Gelécul Family Archive

An ultra-rare Icefire Hudson Bay Blanket—the Holy Grail for collectors of Spitfire memorabilia—is today part of the collection of Icefire mementos kept by Sébastien Bouffard, the grand nephew of 14 Squadron Commander Gelécul. The APRs had a relatively large access panel on the starboard side aft of the roundel that gave access to a large survival kit in case the pilot had to make a forced landing on the ice or tundra. That kit included an inflatable sled (with reinforced bottom that doubled as a raft), a tent, a 14-day ration of pemmican, cans of pickled muktuk, 20 pounds of butter, a Lee Enfield .303 rifle for hunting and protection from polar bears, slitted black silk cloth to slip over the pilots RAF-issue goggles to turn them into snow goggles, snow shoes and two RCAF issue Hudson Bay blankets similar to the one pictured here. Pilots were issued parachutes that were dyed bright magenta for easy spotting by rescuers. Photo: from the Author’s Collection

An ultra-rare Icefire Hudson Bay Blanket—the Holy Grail for collectors of Spitfire memorabilia—is today part of the collection of Icefire mementos kept by Sébastien Bouffard, the grand nephew of 14 Squadron Commander Gelécul. The APRs had a relatively large access panel on the starboard side aft of the roundel that gave access to a large survival kit in case the pilot had to make a forced landing on the ice or tundra. That kit included an inflatable sled (with reinforced bottom that doubled as a raft), a tent, a 14-day ration of pemmican, cans of pickled muktuk, 20 pounds of butter, a Lee Enfield .303 rifle for hunting and protection from polar bears, slitted black silk cloth to slip over the pilots RAF-issue goggles to turn them into snow goggles, snow shoes and two RCAF issue Hudson Bay blankets similar to the one pictured here. Pilots were issued parachutes that were dyed bright magenta for easy spotting by rescuers. Photo: from the Author’s Collection

In October of 1944, German weather station operators on Greenland surrender to United States Coast Guardsmen. The Martin Bay weather station was not the only one deployed during the Second World War. In fact, dozens were set on remote locations in Labrador, Greenland, Svalbard Island, Jan Mayen Island and Iceland. Photo: USCGS

A Canadian search team looks over the nearly intact Weather Station WFL-26, Kurt in 1981. The Germans had scattered American cigarette packs around the installation to throw off suspicion if local hunters had found it. One of the canisters read: “Canadian Meteor Service”, though the station was not on Canadian soil (Labrador and Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949). Its discovery is well explained in a Wikipedia entry: “The station was forgotten until 1977 when Peter Johnson, a geomorphologist working on an unrelated project, stumbled upon the German weather station. He suspected it was a Canadian military installation, and named it “Martin Bay 7”. Around the same time, a retired Siemens engineer named Franz Selinger, who was writing a history of the company, went through Sommermeyer’s papers and learned of the station’s existence. He contacted Canadian Department of National Defence historian W.A.B. Douglas, who went to the site with a team in 1981 and found the station still there, although canisters had been opened and components strewn about the site. Weather Station Kurt was brought to Ottawa and is now on display at the Canadian War Museum.”

In 1948, James Archibald Houston, a veteran of the Second World War and an artist, travelled to the Eastern Canadian Arctic to live and to paint. Having just completed his art studies at the prestigious Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, his goal was to paint the spectacular landscapes that inspired Canadians like Lawren Harris, but he found there an aboriginal art form that would change his life forever and make him one of the most influential figures in Inuit carving and artwork. Houston focussed much of his study and collecting of Inuit art in the area of Cape Dorset in the far north and on the eastern coastline of Hudson Bay, but made one journey by boat down the fiord-riven coast of northern Labrador. It was here, near the old Leutonian mission site at Hebron Fiord, that he came across a small carving in walrus ivory that shook his previous notions about Inuit art forms and cultural norms. A veteran of the Second World War, Houston was very familiar with the legendary Spitfire, and was astonished, some say gob-smacked, when he was offered this small carving among others he was trading for. Photo: National Gallery of Canada

For a people used to portraying the animals, people and objects of a simple existence, the appearance of the strange mechanical white birds of prey, which they called “Ookpiks” or Snowy Owls resulted in a rare piece of Inuit sculpture—a small handcarved effigy of a Spitfire carved from the ivory of a walrus tusk. The piece was offered to James Houston by its carver, the legendary Leutonian/Inuit artist and shaman known as Albert Priiuk, who some called “The Bone” for his ability with ivory and whale bone. About 3.25 inches long with a foreshortened wingspan of just 2 inches, the work is typical of Priiuk’s work—simple, expressive, and observant. What is not typical, of course, is that it is not of a living animal or depicting an Inuit relationship with an animal or the land. Photo: National Gallery of Canada

The underside of carver Priiuk’s magnificent Spitfire effigy in walrus ivory intrigued James Houston greatly, for Inuit artists were not known at that time to sign their artwork. Only as recently as the 1870s had Leutonian and Anglican missionaries introduced a written language to the Inuit, employing geometric syllabic shapes similar to those used by the Cree in northern Québec. The use of the syllabic form was not in wide use on the coast of Labrador in the late 1940s, but Houston had seen it on the Cree coast of Hudson Bay. Through an interpreter, Priiuk explained that it was the Inuit word for Snowy Owl—Ookpik. Houston traded a hunting rifle and scope for the small sculpture and it remained in his personal collection until his death in 2005 at the age of 83. He bequeathed the piece to the National Gallery of Canada. Photo: National Gallery of Canada

Some of the canisters and equipment from Sommermeyer’s weather station on display at the Canadian War Museum on Ottawa. The camouflage pattern was copied from rare photographs of Kurt taken after its installation at Martin Bay. Photo: wwiimodeller.com

Not very often, but every once in a while, an Icefire will grace the tables at Canadian competitions of International Plastic Modelers Society, this one by 86-year old James Montgomery of Mississauga's Aerobuffs club, who is old enough to have heard first hand the unique stories of Squadron Leader Stéphane Gelécul’s 14 Squadron. Montgomery went on to be a mechanical engineer who worked on the Avro Arrow, another all-white Canadian flying legend. Photo: James Montgomery

The Icefire has long inspired Canadian model builders as the one truly Canadian mark of the great Spitfire lineage. Here, Jorge Picabea of France has built an uber-light weight, elastic-powered Spitfire A.PR.IX in the markings of one flown by his uncle Squadron Leader Stéphane Gelécul. Photo: Jorge Picabea