MANUFACTURING VICTORY

Despite researching material over the past five years for the nearly three hundred stories, albums, features and missives of Vintage News, I am still in awe of the historical, emotional and visual matrix that is the world wide web. While I am well aware that the web is not a universe of truth, fact, scholarly wisdom and purity of intent, it still astounds me every day for its ability to deliver to my hungry eyes images, stories and stored memories of humanity's recent and sometimes cataclysmic history.

In particular, it is my wont to follow leads and key words to find information and images that support our stories of Canada's aviation heritage and the heroes who populate this extraordinary and courageous legacy. I am, not weekly, not daily, but nearly every minute amazed by the images that I come across whilst researching a story's background. More than likely these photos may have nothing immediately to do with the story I am background checking. For a couple of years, I just gawked like a Sunday driver passing an accident scene and then moved on, but a couple of years ago, I opened a folder on my computer's desktop which I called Random Beauty, and into which I dragged the images that caught my eye. Soon, there were hundreds of these digital images and Random Beauty became an annual feature of Vintage News, sharing with our readers those riveting and sublime photographs found serendipitously and with apologies, lifted.

Over the past two years, I have divided this folder into a number of sub-categories with the intent of collecting images which were linked or of a similar subject until a critical mass was achieved and from this a story or feature might possibly emerge. I have folders with titles such as Large Aircraft Formations, WTF?, Burning Aircraft, Bad Taste Nose Art, Heroic Portraits, Martin Marauder, or Vintage Aviation Advertising. A year ago one of those folders, Low Flying, reached this critical mass and spawned a story entitled Lower Than a Snake's Belly in a Wagon Rut that went viral around the world and netted our website more than 100,000 visits in two months. Before that, another called The Squadron Dog told the story of the curs, mutts and pedigreed pooches that have permeated air force operation history since Orville and Wilbur and the Saint Bernard they called Scipio. Now, another of these collections, a folder called Aircraft Assembly Lines, has matured and gestated enough for me to wring from it a story. This is not a story told by someone who has extensively studied the production of Second World War Allied aircraft, but rather by someone who is simply in awe of it. Please correct me when I am wrong.

Some of the most compelling images I have ever seen of the Second World War are those which show the Ford Motor Company's Consolidated B-24 Liberator assembly line at Willow Run, near Ypsilanti, Michigan. Though Ford did not design the massive, slab-sided, utilitarian-to-the-bone, four-engined heavy bomber, the company's 40 years of assembly-line experience was brought to bear and Willow Run became perhaps the greatest example of America's military industrial might, ingenuity, determination, and commitment. Ford acquired the license to build Liberators, took the already well-developed science of the aircraft assembly line and elevated it to gargantuan, robotic and almost nightmarish (for the enemy anyway) proportions. At its peak, the plant employed 42,000 people.

At full operational capacity, Willow Run produced 650 B-24 Liberators in one month, one an hour in two shifts. By 1945, despite there being two other Liberator plants, Willow Run accounted for 70% of monthly B-24 production. The B-24 was built in staggering numbers, more than 18,000 in all. Willow Run, only a licensed manufacturing facility, produced 8,700 of them. Pilots and crews slept in a dormitory with 1,300 cots, awaiting the near hourly birth of a new bomber. The Willow Run plant was so large, it threatened to extend into two counties. In order to avoid paying taxes in both counties, Ford turned the assembly line 90 degrees about two thirds along its length. At this point were massive turntables which rotated partially assembled Liberators so that output could continue unabated. These became known as the “Tax Turns”.

The images of Willow Run, which are on the web in the hundreds, show two parallel lines of diagonally parked, overlapping and hulking B-24s in the final assembly hall marching off, not into the distance, but rather into what seems like infinity. One just has to consider the great hulking size of each of the “Libs”, extrapolate this dimension in one's head and the resulting realization of the shear volume of industrial space contained is breath-robbing. The overhead lighting is brilliant, infinite and galactic, indisputable evidence of power and energy unmolested by military threat from enemy aircraft. It is the luminescence of Victory, the incandescent glow on Inevitability.

The seemingly infinite Willow Run B-24 Assembly Line – Its output was the whirlwind reaped by Hitler. Photo via the CarGurus Blog

Looking at these images, I imagine in my mind the musical score of the contemporary animated Disney feature, Fantasia playing on the PA system throughout the factory. Like the rapidly multiplying and infinitely disturbing images of robotic and multiplying brooms with buckets overwhelming Mickey Mouse in this movie, I see a force unleashed by the Axis aggression, a force for which they did not have the command or magic word to stop. Inexorable, relentless, angry, terrifying are words that come to mind.

If the Nazis or the Imperial Japanese were thinking men first and not steadfastly and blindly militaristic; if they could have paused the war in 1944, stepped back and seriously considered the implications for their countries, the consequences for their families; the simple odds; the complete impossibility of success; if they could have visited America, then a guided tour of the godless, churning, 3 1/2 million square foot aircraft assembly machine at Ford's Willow Run would have shaken them to their very Teutonic and bushido-ic souls. They would surely have realized that behind the endless output of Willow Run, there stood phalanx upon phalanx of similarly sized, victory-inspired factories spread across the land – East from Inglewood and Burbank, California and Seattle, Washington to Kansas and on to Farmington, Long Island and South from the heavy industrial belt city of Buffalo through the heartland to Fort Worth, Texas. The great manufacturers, born with the early race to conquer the air, and who would eventually devour each other, worked then in concert for the goal of ultimate victory – Beech, Bell, Boeing, Brewster, Consolidated, Curtiss, Douglas, Grumman, Lockheed, Martin, North American, Northrop, Republic, Seversky, Vought, Vultee and many more.

Related Stories

Click on image

Willow Run - the zenith of mass production of mass destruction.

Not only did Willow Run have barracks for up to 1,300 air crew members, but it had the equivalent of a community college, training young unskilled workers, both male and female, to build one of the most modern combat aircraft of its day. A full-sized mock up of the Liberator's structure can be seen built from plywood behind these students who are learning about a component in this photo. Photo dates from August of 1942. Photo: Ford Motors

Liberators nearing completion move inexorably toward their finish and toward the 90 degree turn in the assembly line - note the B-24s moving to the right in the background. Photo: Ford Motors

Workers install engine components, turrets and machine guns as the Libs head down the line in November of 1944. Photo: Ford Motors

Pre-constructed large components such as rear and forward fuselages undergo inspection and await joining on the Willow Run assembly line in late 1944. Photo: Ford Motors

Another view of the same fuselage storage hall, but from the other side showing the forward fuselage and cockpit sections ready for mating with the aft fuselage. Workers can be seen inspecting the cockpit sections. Everything appears to be ready to connect. Even the wiring harnesses on the right side of the section of each cockpit are bundled in identical fashion. Inside the rear fuselages we can see oxygen bottles and on each fuselage component (forward and aft) we can see the lifting rings used to hoist the weighty components onto the line. These would be removed later. Photo: Ford Motors

Some of Willow run's assembly line workers pose with the 7,000th Ford-built B-24 Liberator (s/n 44-50267, known as “The Lucky 7”) to come off the Willow run Line. Photo: Ford Motors

Painted, marked and primed for action in January of 1944 at Willow Run, these Liberators are now 100% complete and await the daylight. To the left are the massive hangar doors through which the Liberators will now be towed. Photo: Ford Motors

Perhaps two days output of immaculate and no-time Liberators gleam in the Michigan sunshine and await test or delivery crews. Photo: Ford Motors

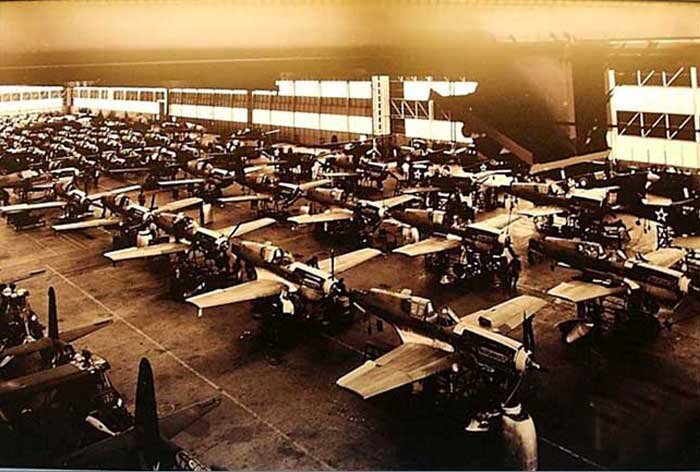

B-24 Liberators in final assembly at the one of several enormous factories (possibly Fort Worth) in the United States purpose built to produce the type. Production of B-24s increased at an astonishing rate throughout 1942 and 1943. Consolidated Aircraft tripled the size of its plant in San Diego and built a large new plant outside Fort Worth, Texas. More B-24s were built by Douglas Aircraft in Tulsa, Oklahoma. North American Aviation built a plant in Dallas, Texas, which produced B-24Gs and B-24Js. None of these were minor operations, but they were dwarfed by the vast new purpose-built factory constructed by the Ford Motor Company at Willow Run near Detroit, Michigan. Ford broke ground on Willow Run in the spring of 1941, with the first plane coming off the line in October 1942. It had the largest assembly line in the world (3,500,000 ft²/330,000 m²). At its peak, the Willow Run plant produced 650 B-24s per month in 1944. Pilots and crews slept on 1,300 cots at Willow Run waiting for their B-24s to roll off the assembly line. At Willow Run, Ford produced half of 18,000 total B-24s.

On April 17, 1942, the first of three thousand B-24 Liberator bombers rolled out of the new mile-long Fort Worth assembly building of Air Force Plant 4—known locally as the “bomber plant”. After Pearl Harbor the city lobbied the government to build a defense installation here, offering 1,400 acres on Lake Worth. The result was Air Force Plant 4, which opened in 1942, operated by Consolidated Aircraft. When the war had begun, Fort Worth had 176,000 people; Tarrant County had 225,000. During the plant’s peak in 1944-1945 Consolidated employed 38,000 workers. That’s one in five Fort Worth residents, one in six county residents. Probably most blocks in Fort Worth had at least one resident who worked at the bomber plant. Air Force Plant 4 produced B-24s for two years.

B-24s under construction at Willow Run, disappear into infinity, swarmed by factory workers.

B-24s in the Consolidated-Vultee Plant, Fort Worth, Texas–the other Liberator Plant. In foreground are Liberator bombers while to the rear of this front line are C-87 "Liberator Express Transports" in various assembly stages. The second line is composed entirely of B-24 Liberator bombers in final assembly stages. Photo via Hometown by Handlebar Blog

A total off 18,482 B-24s were built by September 1945. At Ford's giant Willow Run plant, which was built to use the "Ford Production System", they built one four-engine Liberator an hour, and by the end of the war a total of 8,700 were delivered from Willow Run alone.

Ordinary household demand for goods was low with rationing, and military demand was high. Industry went where the markets demanded–where the money was. Companies that had previously made tires, rolling stock for the railways or refrigerators now made sophisticated combat and transport aircraft. The scores of titanic assembly lines were supplied in turn by hundreds and hundreds of smaller, yet still substantial sub-assembly factories and those in turn were fed by materials factories and component shops in a complex web that blanketed America. And this was merely the aircraft industry. Layer on top of this shipbuilding, armor, weapons and munitions manufacturing, not to mention a nascent nuclear weapon industry, and the fate of our enemies was sealed the day they the convinced themselves it was a good idea to take what belonged to their neighbours.

America and its massive size was certainly the key, but it was not the only contributor to this mighty output of war machinery. After establishing aerial dominance over their homeland early in the war, the Brits would up their war output to dizzying levels, newly minted and massive Lancaster and Halifax bombers being towed off their assembly lines in astounding numbers. Factories for Airspeed, Armstrong-Whitworth, Avro, Blackburn, Bristol, de Havilland, Fairey, Gloster, Handley Page, Hawker, Miles, Short, Supermarine, Vickers, Westland and others designed and produced the flying machines that won back British security under the onslaught of the Nazi war machine. Long before Willow Run's enormity or Boeing's massive expansions, the famous Castle Bromwich plant was flying off many thousands of Spitfires to join the fight against tyranny.

A mouth watering sight for Spitfire lovers today - dozens of centre section fuselages of late model blown-canopy spitfires, possibly Mk XVIs.

Canada, previously a lightweight in the world of aeronautical manufacturing, yet gifted with natural resources, energy, an educated workforce and safe skies, rapidly tooled for war, starting with the training aircraft that would colour the Canadian countryside yellow during the war years. To provide the thousands of trainers needed for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, traditional commercial aircraft manufacturers like de Havilland Canada, Fleet, Noorduyn and Fairchild built copies of foreign mother company designs, while other heavy industrial manufacturers like National Steel Car and Canadian Car and Foundry rejigged for aeronautics. There were Finches, Tiger Moths, and Cornells for elementary flying training and Harvards, Yales and Ansons for service flying and navigation training, Lysanders for target towing, Fleet Forts for wireless training, and Hurricanes and Bolingbrokes for OTUs.

Some Canadian manufacturers were already building American combat aircraft before that country entered the fight, and by war's end, companies like Victory (formerly National Steel Car and later Avro Canada), Canadian Vickers and de Havilland were constructing large numbers of premier Allied combat aircraft under license, including the Mosquito, Bolingbroke (Blenheim), PBY Canso, and Lancaster Mk X. In the same manner, Australia, faced with a long supply chain, spooled up its own aeronautical industry, license building Mosquitos, Tiger Moths, Beauforts, Beaufighters and others. Throw into that mix the massive output of the Soviet Union which, in just one spectacular case, built more than 38,000 Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik ground attack aircraft and one comes to the rapid understanding that the outcome of the Second World War, though seemingly threatened at times, was never in going to be in favour of the Axis.

Now, there is no doubt that the German and Japanese war machines had enormous capacity to construct quality aircraft. The German assembly lines for Arado, Dornier, Focke Wulf, Heinkel, Henschel, Horten, Fieseler, Junkers, Messerschmitt and others, were efficient, continuously operating despite the constant disruption of Allied bombing and above all, spectacularly innovative and creative. But, frankly speaking, regardless of the talent, the teutonic militarism, the blind belief in supremacy and the organizational skills of Albert Speer, they were about to be flattened by a tsunami of steel, aluminum and explosives.

There will be those who think it was a closer thing and say "What If?” and cite the pressures and so-called close calls of the U-boat war, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain, the setbacks of the early war and other well-fought battles by the Axis. None of this matters in the face of Allied war production and particularly that of North America.

It was written on the walls of the main assembly hall at Willow Run. It was in the proud gaze of female workers who stepped up to the plate across the allied landscape. It was written in the signatures of the thousands and thousands of Boeing employees inscribed on the 5,000th Flying Fortress to roll off the assembly line at Seattle. In May, 1944, there was much pride, excitement and public relations hoohah surrounding 5 Grand, the Fortress in question, but by the time the last had rolled off the line in 1945, no one cared. Relentless, rhythmic, robotic production was simply a way of life, a way to bury the enemy.

The German war production machine was a thing of beauty in the early years of the war, but the Germans suffered from one very serious industrial problem – the war surrounded them on all their borders or the borders of the countries they conquered. All factories were simply within range, and subjected to the merciless rain of explosives from Allied enemy bombers. While they still made huge outputs throughout the war, they were molested, interrupted driven underground, short on materials, short on skilled workers and never, ever had any chance to spool up to match production, aircraft for aircraft, with their enemies.

Enough talk, how about a glimpse of the many found in the folder entitled Aircraft Assembly Lines? Given the broad range of material found I suspect there will be instances where I am out and out wrong or have misinterpreted what I read. I would welcome corrections, and even additions, but the real story is not necessarily in the details, but rather in the immensity of the Allied enterprise, which could not be denied.

Dave O'Malley

Pre-war production - slower, and on a smaller scale

When aviation was just 15 years old, war production was a much simpler, hand-crafted business. Assembly lines were not yet employed anywhere near the extent they would be 25 years later. Here, in 1917 at the Vought factory, VE-7 “Bluebird” fuselages await wings at the plant in Astoria New York. 25 years later, Vought would be making a blue bird of considerably more complexity and power... the F4-U Corsair.

The Canadian Aeroplanes Limited factory in Toronto, circa 1917/1918 - poorly lit, cramped and with no evidence of an assembly line. This was the beginning of the aerospace industry in Canada. They built JN-4C Canucks (Canadian versions of the Curtiss Jenny) for the RFC Canada (later RAF Canada) training scheme. It was somewhat of a prototype for the BCATP, both in terms of training aircrew in Canada who would fight in Europe - and in terms of developing an aircraft industry. Just 20 years later, full aircraft assembly plants in the modern style would be built in Canada. Photo via Edward Soye

Prior to the war, aircraft production was on a much smaller scale. Here, fuselages for the Northrop A-17 monoplane bomber await further work. The Northrop A-17 “Nomad”, a development of the Northrop Gamma 2F was a two seat, single engine, monoplane, attack bomber built in 1935 by the Northrop Corporation for the U.S. Army Air Corps and was used by the RCAF as part of the BCATP.

At the end of the 1930s, the United Sates was beginning to power-up the war manufacturing machine. Plants became bigger, but not to the extent they would become in a few short years. Here we see U.S. Navy Douglas TBD-1 Devastator torpedo bombers pictured in various stages of assembly at Douglas Aircraft Company's Santa Monica, California (USA), plant. This was long before the United Sates entered the war. and the plant floor looks much quieter and slower than factories of the late war period. The Douglas TBD Devastator was a torpedo bomber of the United States Navy, ordered in 1934, first flying in 1935 and entering service in 1937. At that point, it was the most advanced aircraft flying for the USN and possibly for any navy in the world. However, the fast pace of aircraft development caught up with it, and by the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the TBD was already outdated. It performed well in some early battles, but in the Battle of Midway the Devastators launched against the Japanese fleet were almost totally wiped out. The type was immediately withdrawn from front line service, replaced by the more capable Grumman TBF Avenger.

Curtiss SB2C Helldiver aircraft near completion at Canadian Car and Foundry in Fort William, Ontario (Now Thunder Bay). Prior to the American entry into the Second World War, the Curtiss Aircraft Co. increased production of SB2C Helldiver naval aircraft by licensing construction to two Canadian companies - Fairchild Aircraft and Canadian Car and Foundry. Though the first flight of the prototype did not happen until December of 1940, large-scale production had already been ordered on 29 November 1940. A large number of modifications were specified for the production model and the program suffered so many delays that the Grumman TBF Avenger entered service before the Helldiver, even though the Avenger had begun its development two years later. Nevertheless, production tempo accelerated with production at Columbus, Ohio and two Canadian factories: Fairchild Aircraft Ltd. (Canada) which produced a total of 300 (under the designations XSBF-l, SBF-l, SBF-3 and SBF-4E) and Canadian Car and Foundry which built 894 (designated SBW-l, SBW-3, SBW-4, SBW-4E and SBW-5), these models being respectively equivalent to their Curtiss-built counterparts. A total of 7,140 SB2Cs were produced in World War II. Photo: Archives of Ontario

Another view of the Canadian car and Foundry Helldiver line at Fort William. Photo via Jim Bates

Another view of the Canadian car and Foundry Helldiver line at Fort William. Photo via Jim Bates

Early model B-17 Flying Fortresses at Seattle, before the massive retooling and high-production rate of the latter years of the war. In fact it was not uncommon to see other aircraft types, even commercial aircraft, sharing the same assembly lines. Here we see Boeing 307 Stratoliners in the background. In 1935 Boeing designed a four-engined airliner based on its B-17 heavy bomber (Boeing Model 299), then in production, calling it the Model 307. It combined the wings, tail, rudder, landing gear, and engines from their production B-17C with a new, circular cross-section fuselage of 138 in (351 cm) diameter,designed to allow pressurization. It wasn't long before commercial aircraft construction had ceased and entire new plants created to do one thing... build bombers. Only ten Stratoliners were built and TWA sold back their five airframes to the Army when war was declared. They became known as the C-75 and were returned to TWA in 1944. Boeing Photo

Another early shared assembly line. The Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat and G-21 “Goose” share assembly areas at the Grumman plant at Bethpage, Long Island. The arrival of the Second World War saw the Goose (a name originally bestowed on the aircraft by the Royal Air Force) enter military service with a number of allied air arms, the largest operator being the US Navy. Military orders from the US, Britain and Canada accounted for much of the Goose's 300 unit production run. The Goose in the foreground is clearly destined for either the RCAF or RAF. The Wildcats are marked in the early-war (1942) US Navy scheme of non-reflective blue-grey over light grey scheme.

Production beneath the Threat of Aerial Attack

Lancaster production at A. V. Roe's Chadderton plant. The old Newton Heath Factory served Avro well throughout the 1920s and 1930s, but with war imminent, it was announced by the government that Avro would build a large new factory. The site chosen was in Chadderton near Oldham. Aircraft production commenced soon afterwards although not with an Avro Design, but with the Bristol Blenheim light bomber which Avro built under license. This type was soon followed by the Avro Manchester twin engined bomber, but trouble with the engines forced the company to search for alternative power plants. The answer came with the excellent Rolls-Royce Merlin which powered the famous Spitfire and Hurricane fighters. With four of these engines installed in a modified Manchester, the Avro Lancaster, the most famous British bomber to emerge from the Second World War, was born. The town of Chadderton is known as the Rose of Lancaster.

Lancaster rear sections, fully assembled and painted await mating to the front sections at A V Roe's Woodford Plant. Photo via Richard Mallory Allnutt

Lancaster rear sections, fully assembled and painted await mating to the front sections at A V Roe's Woodford Plant. In June of 1944, the 1/4 mile long Woodford factory reached its manufacturing zenith, producing 156 Lancaster bombers in one month. The plant, owned by BAe Systems, closed down permanently just last year. Photo via Richard Mallory Allnutt

Fairey Battle Production line circa 1940. There are at least 19 airframes in this photograph. At about this time, the Battle was seen as obsolete and non-competitive as a fighter/bomber. Even though it recorded the first aerial victory of the war for the RAF, mission losses during the “Phoney War” and the Battle of France topped 50%! Most of the remaining airframes made their way across to Canada where they became bombing and gunnery trainers. Fairey Aviation was a major supplier of aircraft to the RAF & the Fleet Air Arm during World War Two. Besides building its own designs it also sub-contracted for other companies such as Handley Page, Bristol & Avro. The factory was a key component of the British war effort, and as such needed to be defended. The factory was camouflaged & had anti-aircraft defences & armed guards.

Bromwich Castle plant was built in 1936 and was known as the Castle Bromwich Aircraft Factory. CBAF was first managed by the Nuffield Organization to manufacture Spitfires and (later) Lancaster bomber aircraft. After the war, the factory ceded to automobile production, and eventually was fully taken over by Jaguar Cars in 1977.

The large Castle Bromwich factory at the height of Spitfire production, with mechanics making good use of crates and pallets as scaffolding. By May 1940, Castle Bromwich had not yet built its first Spitfire, in spite of promises that the factory would be producing 60 per week starting in April. Mid-May, Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production, telephoned Lord Nuffield and manoeuvered him into handing over control of the Castle Bromwich plant to Beaverbook's Ministry. Beaverbrook immediately sent in experienced management staff and experienced workers from Supermarine and gave over control of the factory to Vickers-Armstrong. Although it would take some time to resolve the problems, in June 1940, 10 Mk IIs were built; 23 rolled out in July, 37 in August, and 56 in September. By the time production ended at Castle Bromwich in June 1945, a total of 12,129 Spitfires (921 Mk IIs, 4,489 Mk Vs, 5,665 Mk IXs, and 1,054 Mk XVIs) had been built. CBAF went on to become the largest and most successful plant of its type during the 1939-45 conflict. As the largest Spitfire factory in the UK, by producing a maximum of 320 aircraft per month, it built over half of the approximately 20,000 aircraft of this type.

Final assembly hall with of Spitfires, Castle Bromwich Aero Factory 'C' Block, around 1943. Compared to American factories, British facilities always seem to be much dimmer. Perhaps this is the result of lower energy resources. Photo, City of Birmingham [LSH: WK/C1/147]

While there exists today only three exhibit-only Handley Page Halifax airframes, there was a time when they crowded the factories across England. Halifaxes were assembled from pre-built sub assemblies. Total Halifax production was 6,178 with the last aircraft delivered in April 1945. In addition to Handley Page, Halifaxes were built by English Electric, Fairey Aviation, and Rootes Motors in Lancashire and by the London Aircraft Production Group. Peak production resulted in one Halifax being completed every hour. This photo shows Halifax B Mk 111 forward fuselages at the Fairey's Errwood Park works, 24 February 1944. Photo: R.A. Scholefield, Airliners.net

Bristol Blenheim Mk V bomber in a dim at the Bristol Factory in Filton, England in March 1943

Mossies on the line at Leavesden. One of the major advances in aircraft technology to come out of the period of the Second World War was the De Havilland Mosquito. This amazing aircraft, which first flew on the 25 November 1940, out performed all Allied and Enemy aircraft - it was 23 MPH faster than the Spitfire with the same engines, and the fastest production aircraft in the world for two and a half years of the War. A larger de Havilland factory at Leavesdan, Herts The Hatfield factory was set up for Mosquito production, a new factory was built at Leavesden, production lines at Standard Motors factory at Coventry, Airspeed at Portsmouth, Percival Aircraft at Luton, production of parts and materials was dispersed all over southern England, by 1943 over 100 Mosquito’s a month rolled out, by 1945 almost double that. Production had also started in Canada and in 1943 the first Mosquito rolled off the assembly line at Bankstown in Australia.

Wooden wing assemblies are mated with de Havilland Mosquito fuselages at the de Havilland facility at Hatfield in 1943. Typically, British aircraft factories were older and smaller. Imperial War Museum photo

Hawker Hurricanes at Brooklands. The Hurricane was produced at the Hawker factories in Canbury Park Road, Kingston-upon-Thames, and then assembled at the Hawker shed at Brooklands, Weybridge, or, from 1942, at the Hawker aerodrome at Langley, near Slough (the famous hometown of the fictitious Wernham Hogg Paper Company of the Rocky Gervais original TV series “The Office”). Clearly, the Hurricane was a fighter aircraft from another era, employing both skilled wood and metal workers to construct its complex fuselage. Photo: Brooklands Museum archive courtesy of BAE Systems

Women went to war by replacing men in factories and doing an equally excellent job, some say better. Where German factories were employing slave labour, women of Allied countries flocked in the millions to enter the work force and demonstrate their equality. Hawker employees Winnie Bennett, Dolly Bennett, Florence Simpson and a colleague at work on the production of Hurricane fighter aircraft at a factory in Britain, in 1942.

German Production - under constant threat

In 1941 when this photo was taken, the Junkers factory in Dessau was churning out Ju 88 multi-role aircraft. It is clear that the factory had not yet suffered the scourge of Allied bombing. Despite its protracted development, the Ju 88 became one of the Luftwaffe's most important assets. The assembly line ran constantly from 1936 to 1945, and more than 16,000 Ju 88s were built in dozens of variants, more than any other twin-engine German aircraft of the period. The bulk of these would eventually be destroyed in the war. Throughout the production, the basic structure of the aircraft remained unchanged, proof of the outstanding quality of the original design. Today, the site of the factory now houses the TechnikMuseum Hugo Junkers Dessau.

JU-87B Stuka production on the assembly line at Weser Flugzeugbau at Berlin-Templehof. Here fuselages get to meet their Junkers Jumo 211D liquid-cooled inverted-vee V12 engines. Weser Flugzeugbau GmbH, known as Weserflug, was the fourth largest aircraft manufacturer in Second World War Germany. During 1940-5, Weserflug built 5,215 Junkers Ju 87 Stuka aircraft at Tempelhof. This plant also constructed Fw 190 fighters. Forced labour was used at the plant to supplement the diminishing German workforce – on 20 April 1944, 2,103 of the 4,151 Tempelhof workers were foreign forced labourers.

Early production line of the Ju 87 Stuka - workers take the time to lay down covers on the wings.

With engines mated to their fuselages, these Stukas near the end of their construction

The scourge of Junkers and other German manufacturers was the destruction wrought by aircraft which were manufactured in Allied plants which never had the same done to them. Here we see Ju-87 Stukas wrecked along with the assembly facility which made them.

Clearly, the Ministry of Propaganda controlled this photo of an overly clean and tidy Messerschmitt Bf 109 assembly line in Regensburg. The propellers are all lined up, canopies all open and it seems German aircraft workers don't use tools. Despite never having a chance to match Allied aircraft output, the Germans did manage to build an astonishing 34,000 Bf 109s. Bf 109s remained in foreign service for many years after World War II. The Swiss used their Bf 109Gs well into the 1950s. The Finnish Air Force did not retire their Bf 109Gs until March 1954. Romania used its Bf 109s until 1955. The Spanish Hispanos flew even longer. Some were still in service in the late 1960s. They appeared in films (notably The Battle of Britain) playing the role of the Bf 109. Some Hispano-built, Merlin-powered airframes were sold to museums, which rebuilt them as Bf 109s.

Partly completed Heinkel He-162 fighter jets sit on the assembly line in an underground factory in Germany, in early April 1945. By this time, production was still progressing, but suffered from having to be hidden from the aluminum overcast which rained down explosives from the sky and also from a poorer quality labour force. The Germans in general spread their production out away from major factories, to much smaller assembly lines. They built them in caves, and salt mines, and even in forests even. Production quality, however, was another thing entirely. They relied on slave labor too, which made reliability another issue as well, due to sabotage and understandably sloppy workmanship. These huge underground galleries, in a former salt mine, were discovered by the 1st U.S. Army during their advance on Magdeburg. The Heinkel He 162 Volksjäger (German, "People's Fighter") was a German single-engine, jet-powered fighter aircraft fielded by the Luftwaffe in World War II. Designed and built quickly, and made primarily of wood as metals were in very short supply and prioritized for other aircraft, the He 162 was nevertheless the fastest of the first generation of Axis and Allied jets

Building Big Boeing Bombers

It was the building of thousands and thousands of the big Boeing bombers like the B-17 Flying Fortress without the threat of attack and with unlimited resources at hand that sealed the fate of the Axis powers. On the ground in the battlefields, it was the Allied soldier that beat them back, but behind him there was awesome assurance of millions of countrymen working to supply the tools. Here B-17s are assembled at Boeing's Plant 2 in Seattle, Washington

The vast halls of Hitler's demise. Hundreds of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress being assembled during World War II at Plant 2, in Seattle. Photo: The Boeing Company

Boeing sub-contracted the building of the Flying Fortress to Douglas and Vega Aircraft to keep up to demand. The partnership between Boeing, Vega (a subsidiary of Lockheed) and Douglas was abbreviated as BVD. Here we see a nearly complete B-17G fuselage moving down the Vega assembly line. Of over 12,000 B-17s produced by war's end, 2,750 were built by Vega. The company also built two experimental B-17 variants, the XB-38 and the B-40.

Camouflaged on its roof to resemble a residential neighborhood the Boeing Plant 2 facility in Seattle really never had to worry about attack. The Vega plant had a similar treatment. The factory was located next to Burbank's Union Airport which it had purchased in 1940. During the war, the entire area was camouflaged to fool enemy aerial reconnaissance. The factory was hidden beneath a huge burlap tarp painted to depict a peaceful semi-rural neighborhood, replete with rubber automobiles. Hundreds of fake trees, shrubs, buildings and even fire hydrants were positioned to give a three dimensional appearance. The trees and shrubs were created from chicken wire treated with an adhesive and covered with feathers to provide a leafy texture.

Despite earlier fears of attack from the Japanese, the Seattle Boeing Plant 2 complex made good use of outdoor storage of recently finished Fortress bombers.

B-17s being built under license at the Douglas Plant (part of the BVD partnership) at Long Beach, California. Compare this galaxy of overhead lighting to the dim interiors of European factories such as Supermarine Vickers Castle Bromwich plant.

B-17s nearing completion trundle down the line past stored nose glazing units and other components. Can't be sure of this, but the lighting style looks like the Douglas B-17 plant in Long Beach.

When the 5,000th Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress (337716) started life on the assembly line, the company made huge Public Relations hay from the opportunity. every one of the many thousands of employees at Boeing's Seattle plant came to sine or stencil their names on its all metal sides. When it rolled off the line, it was greeted by a reception of plant employees. The skin was left bare metal with the signatures when it went into an operational squadron, nicknamed “5 Grand”. Special permission given by the USAAF to carry the signatures of all those men and women who assembled this flying machine.

The Story of 5 Grand

In May 1944 5 Grand was officially delivered to the US Army Air Forces at Boeing Field and a bottle of champagne was ceremonially broken over the aircraft's nose. The USAAF even made sure that the crew assigned to 5 Grand were made up of locals from the Puget Sound area with Edward C. Unger of Seattle selected as the aircraft commander/pilot. 5 Grand was then flown to Kearney AAF depot in Nebraska for further modifications to make her combat ready. When she left the United States for the Eighth Air Force's bomber bases in Britain, over 35,000 signatures adorned the bare metal finish of 5 Grand. Some thought that the plane should be stripped as the Luftwaffe might make special effort to shoot down 5 Grand, but it was decided the signatures would stay in place. On the trans-Atlantic flight, the crew found the B-17G was about 7 mph slower than a stock B-17G due to the weight of the ink and paint used on the signatures and the surface roughness from some of the more colorful applications! The fuel consumption was higher and stronger-than-forecast winds aloft resulted in one of 5 Grand's engines cutting out on landing in the UK due to fuel starvation.

Assigned to the 333rd Bomber Squadron of the 96th Bomber Group at Snetterton Heath in Norfolk, one of its first local flights before combat missions were flown ended in near disaster when the electrical system failed and 5 Grand made a crash landing after ejecting its ball turret. She was repaired and reassigned to the 388th Bomber Group and would fly 78 missions over the Reich adorned with her signatures with her gunners claiming two Luftwaffe fighters destroyed.

A nice colour shot of 5 Grand in flight. The Big Boeing went into battle with these markings. Photo via Richard Mallory Allnutt

On 14 June 1945 5 Grand returned home to the United States, first landing at Bradley Field in Connecticut before continuing on to Boeing Field in Seattle for refurbishment to go on a war bond tour. While in Seattle, many employees found their signatures still in place. Local officials wanted to preserve 5 Grand as a memorial to the city's home front war effort, but while the Seattle politicians debated the cost, 5 Grand was flown to Lubbock AAF in Texas for further repairs and refurbishment before being flown into storage at Kingman AAF in Arizona to be held in storage while Seattle officials decided how to proceed on the planned memorial incorporating 5 Grand. The US Army Air Forces were willing to donate 5 Grand to Seattle for the memorial planned by the Seattle Historical Society, but on 3 January 1946, Seattle city officials declined the donation of 5 Grand on the grounds that building a memorial with the aircraft represented too costly an endeavour.

Despite the efforts of Boeing employees who had signed 5 Grand, no one in the local government wished to take responsibility and the aircraft, still resplendent with its signatures, was sold off by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to the scrapper where 5 Grand was unceremoniously broken up and melted down, forever lost to history. Source: Aeroplane Monthly, June 2010, Volume 38, Number 6. "A Fort Named 5 Grand" by Howard Carter, p40-45

Post war, 5 Grand was scrapped at Kingman, Arizona. The City of Seattle attempted buy it to put it on display. Few people cared and not sufficient money was raised... the 5,000th B-17 with all the names of those who assembled this famous flying machine (plus aircrews who later put their names on it) was scrapped and melted down in an Arizona aircraft bone yard.

A close-up of 5 Grand's tail with names still intact. A real opportunity was missed by the City of Seattle when they refused to fund the retrieval of this unique warbird. It would have been a simultaneous memorial to the men and women who made the B-17 and the Men who flew them into harm's way.

Bigger Boeings Being Built

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress factory in Wichita, Kanas. As Boeing lacked production space at its Renton, Washington, plant, the USAAC wanted production of the B-29 at Boeing Wichita which at the time was building biplane trainers and B-17 control surfaces. This caused a furor in Seattle, but the USAAC insisted on the security of a plant deep inland given that the B-29 would be a game changer once it entered service. Only the first three Boeing B-29s were built in Seattle. The need for expansion at Boeing Wichita resulted in one of the largest population booms of the once quiet Kansas town. But as the flight test program of the B-29 progressed and the war widened in scope, more B-29s got added to the production order. By January 1944 Boeing Wichita alone had orders for 1,630 Superfortresses.

Nothing demonstrates the power and size and game-changing nature of the B-29 Superfortress than this image of female factory workers hand-painting zinc-cromate primer into the interior of a B-29 wing... or rather the trailing half of the wing. What I see here is an abundant supply of workers, aluminum and energy. Zinc Chromate was used as an anti-corrosive barrier primer; it could be described as a sort of painted-on galvanizing. It had been developed by Ford Motor Company by the late 1920s, subsequently adopted in commercial aviation and later by the US Military. Official USAAC notes mention successful application of Zinc Chromate primer starting from 1933, but it had not been adopted as standard until 1936.

A big aircraft like the Boeing B-29 Superfortress needed a super factory. The Battle of Kansas (also known as the "Battle of Wichita") was the nickname given to a project to build, modify and deliver large quantities of the world's most advanced bomber to the front-lines in the Pacific. The battle began as the first B-29 Superfortresses rolled off the production lines of the massive new Boeing factory on the prairies near Wichita, Kansas. The specific B-29 aircraft (44-61535) shown in this photo still exists, or at least part of it does and is outdoor display at the Castle AFB Air Museum in Atwater, CA.

After Boeing B-29A 44-61535 (see previous photo) was rolled off the assembly line, it was taken over by the USAAC, which became the United States Air Force. It was operational until 1957 when it was put into storage at Naval Air Station China Lake until 1980. Here, squadron ground personnel of the 28th Bombardment Squadron, 19th Bombardment Group pose with 44-61535, better known as Raz'n Hell somewhere in the Pacific during the Korean War. Photo via Jay Somnii, @Flickr

In 1980, parts of 44-61535 were combined with components from two other B-29s to make a display aircraft at Castle AFB. The B-29, with only minimal parts from the original 44-61535, is none the less painted to resemble her. The Raz'n Hell serial number is displayed as 44-61535 which was the original Raz'n Hell, however this B-29 is a composite of three aircraft which were used as targets and recovered from from the Naval Weapons Center at China Lake. Nose art was restored by Jay Somnii, the person who sent us the previous Korean war era photo. Photo via Rick Baldridge

North American's Finest

A rare colour view of the B-25 Mitchell final assembly line at North American Aviation's Inglewood, California, plant in 1942. Note the zinc chromate primer paint on the tops of the wings. The Mitchell was arguably the finest twin-engine medium bomber of the war. It was used by many Allied air forces, in every theater of World War II, as well as many other air forces after the war ended, and saw service across four decades.

Zinc chromate covered B-25 bombers being assembled at Kansas City, Kansas. A total of 6,608 B-25s were built at North American's Fairfax Airport plant in Kansas City, Kansas. The remaining 3,376 Mitchells were built in Inglewood, California. Photo: Alfred T. Palmer

P-51Ds on the line at Inglewood, California. The more than 15,000 Mustangs built during the war were manufactured at two North American plants - one in Inglewood and one in Dallas, Texas. The P-51 was one of the first fighters designed to be easily mass produced. The Mustang was designed in a modular fashion, with 3 fuselage sections and 2 wing sections. Each section was built separately before the entire aircraft was assembled.

P-51 Mustang fighter planes in California. An inspector checks over the work done on a P-51 fighter before it moves to the next assembly position at North American's Inglewood, California, plant. This plant produced as well the battle-tested B-25 Mitchell bomber.

Aircraft for the Navy

SBD-5 Dauntless dive bombers pictured on the assembly line at Douglas Aircraft Company's El Segundo Plant, California (USA), 1943. The SBD (short for Scout Bomber Douglas) was the United States Navy's main dive bomber from mid-1940 until late 1943, when it was largely replaced by the SB2C Helldiver and subsequently the Avenger. The aircraft was also operated by the United States Army as the A-24 Banshee. Nearly 6,000 SBD-5s/A-24s were built.

The submarine-like hulls of Consolidated PBY Catalina Flying Boats crowd the line at the New Orleans plant. Consolidated became Consolidated Vultee and by 1943 was Convair. PBYs (The PB stood for Patrol Bomber, while the Y was the Consolidated designated letter) were manufactured by San Diego based Convair in New Orleans, the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, Boeing Aircraft of Canada in Vancouver, and Canadian Vickers (later Canadair) in Montreal

At first I believed this to be an assembly line image, but closer inspection shows these Grumman Hellcats are not really on a line, but rather in heavy maintenance. The giveaway was for me the fact each aircraft has unit numbers on their fuselages, something that would not be put on at the factory, but at the units for which they served. The aircraft seem to be weathered as well. Regardless, the shear size of this repair depot tells the same story.

Fairey Barracuda production line in 1944. This high-winged naval dive bomber was probably the largest aircraft flown off Royal Navy aircraft carriers during the Second World War.

Second World War F4U Corsair Production Line of the Chance Vought aircraft factory in Stratford, Connecticut which produced over 6,000 Corsairs. The Corsair's folding wing feature, necessary for Carrier operations and hangar deck storage, must surely have been a huge benefit on the Corsair assembly line as well.

More Corsairs, with early USN paint scheme (red outline of Star and Bar) near the end of their production line at Goodyear's Akron plant.

Centre wing spar sections of the Vought-designed Super Corsair move along on trolleys at the Goodyear line in Akron, Ohio. Only 10 were built by Goodyear here. Here we see the complex and unique structure that allowed the inverted gull-wing configuration. A total of 12,571 Corsairs were made between 1942 and 1953, there were some minor model variations but most used the 2,000 hp, 18-cylinder, Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial. Power was transmitted through a large Hamilton Standard Hydromatic three-blade propeller with a diameter of 13’4″ (4.06 m).

The finishing end of the Vultee BT-13 Valiant production line, at Downey, California (Near Inglewood). The Vultee BT-13 was the basic trainer flown by most American pilots during the Second World War. It was the second phase of the three phase training program for pilots. After primary training, the student pilot moved to the more complex Vultee for basic flight training. The BT-13 had a more powerful engine and was faster and heavier than the primary trainer. It required the student pilot to use two way radio communications with the ground and to operate landing flaps and a two-position Hamilton Standard variable pitch propeller. It did not, however, have retractable landing gear nor a hydraulic system. The large flaps are operated by a crank-and-cable system. Its pilots nicknamed it the "Vultee Vibrator." The aircraft in the foreground is the Vultee P-66 Vanguard prototype. The Vultee P-66 Vanguard was an accidental addition to the USAAF's inventory of fighter aircraft. It was initially ordered by Sweden, but by the time the aircraft were ready for delivery in 1941, the United States would not allow them to be exported, designating them as P-66s and retaining them for defensive and training purposes. Eventually, a large number were sent to China where they were pressed into service as combat aircraft with indifferent results.

The Baltimore Whore. Being my favourite multi-engined aircraft of the war, I looked hard and long for an image of the Glenn L. Martin company's Martin B-26 Marauder aircraft on the assembly line. 5,288 were built at Martin's Middle River Plant near Baltimore. The regularity of crashes by pilots training on the Marauder led to the exaggerated catchphrase, "One a day in Tampa Bay." Apart from accidents occurring over land, 13 Marauders ditched in Tampa Bay in the 14 months between the first one on 5 August 1942 to the final one on 8 October 1943. B-26 crews gave the plane the nickname "Widowmaker". Other colorful nicknames included "Martin Murderer", "Flying Coffin", "B-Dash-Crash", "Flying Prostitute" (so-named because it was so fast and had "no visible means of support," referring to its small wings) and "Baltimore Whore" (a reference to the city where Martin was based).

Eight B-26 Marauders of the US Army Air Corps, at least three with and three without propellers, on the ramp outside the Middle River factory due to a shortage of Curtiss electric propellers during 1941. Photo: Lockheed Martin

Massive Black Widow twin-engined night fighters on the line in Baltimore. The Northrop P-61 Black Widow, named for the American spider, was the first operational U.S. military aircraft designed specifically for night interception of aircraft, and was the first aircraft specifically designed to use radar.It was an all-metal, twin-engine, twin-boom design developed during the Second World War.The Black Widows were built by the Glenn L. Martin Company located in Baltimore, MD

The First in Full Production

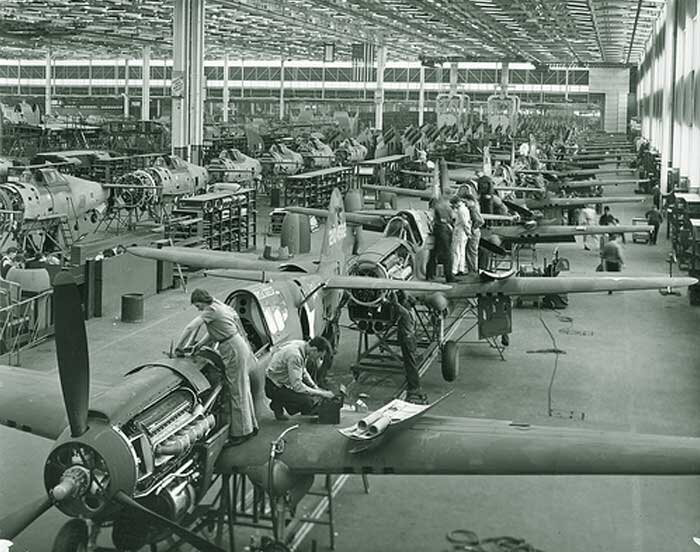

P-40E Warhawks in production at Curtiss Plant 2 on Genesee Street in Buffalo, New York. At its peak, more than 18,000 men and women worked in the Curtiss-Wright plant.

The Curtiss-Wright factory in Buffalo, New York is jammed tight with multiple lines including final assembly of P-40 Warhawk fighters in the foreground and unpainted Curtiss C-46 Commandos.

A close up of C-46s and P-40s in production in 1942 in Buffalo's Curtiss Plant 2. Another Curtiss -Wright plant was built at Louisville and was converted to C-46 Commando production, eventually delivering 438 Commandos to supplement the roughly 2,500 C-46s produced at Buffalo.

The Commando was a transport aircraft originally derived from a commercial high-altitude airliner design. It was instead used as a military transport during World War II by the United States Army Air Forces as well as the U.S. Navy/Marine Corps under the designation R5C. Known to the men who flew them as "The Whale," the "Curtiss Calamity," the "plumber's nightmare", and among ATC crews, the "flying coffin”, the C-46 served a similar role as its counterpart, the Douglas C-47 Skytrain, but was not as extensively produced. At the time of its production, the C-46 was the largest twin-engine aircraft in the world, and the largest and heaviest twin-engine aircraft to see service in World War II. Photo Curtiss-Wright

More P-40 Warhawks near completion in Buffalo, New York. The interesting part of this image is the parallel line of Curtiss-built P-47G Thunderbolts .

The Warhawk (Kittyhawk, Tomahawk,) was used by the air forces of 28 nations, including those of most Allied powers during World War II, and remained in front line service until the end of the war. It was the third most-produced American fighter, after the P-51 and P-47; by November 1944, when production of the P-40 ceased, 13,738 had been built, all at Curtiss-Wright Corporation's main production facilities at Buffalo, New York.

An early shot (Pre-Pearl harbor) of the Lockheed plant in California churning out Hudson medium bombers for the RAF while at the same time building airliners. It was an identical Hudson from this line that crashed at Wakefield Quebec in 1941. Soon all civilian production would stop across America and all effort focused on strictly war production.

Workers are busy on the P-39 Airacobra assembly line at Bell Aircraft’s Niagara Falls plant. By the time the war ended, Bell had produced 9,584 P-39s. Not the most effective fighter of the Second World War, few examples managed to survive; at last count, three were still flying.

Vultee Aircraft Co, Inc., Downey, California, Vultee "Vengeance" assembly line. The Vultee A-31 Vengeance was an American dive bomber of World War II, built by Vultee Aircraft. The Vengeance was not used in combat by US units, however it served with the British Royal Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force, and Indian Air Force in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. As Vultee's factory at Downey was already busy building BT-13 Valiant trainers, the aircraft were built at the Stinson factory at Nashville, and under license by Northrop at Hawthorne, California.

The Vultee BT-13 Valiant line at Downey. A subsequent variant of the BT-13 in USAAC/USAAF service was known as the BT-15 Valiant, while an identical version for the US Navy was known as the SNV and was used to train naval aviators for the US Navy, US Marine Corps and US Coast Guard. The Downey plant was billed at the time "The world's fastest production line".

Fast as Lightning

Mechanized Conveyor Lines - Triple lines for Lockheed "Lightnings" Overall view of Lockheed's new mechanized P-38 line at Burbank, California. Moving continuously, slowly, yet as surely as the hands of a watch, these three mechanized conveyor lines at the Lockheed Aircraft Corp. more than double the daily output of the old assembly line. The P-38 Lightning fighters come down the line at the right and are shunted over to the middle line where they grow their wings and engines. They then move backwards to the far end of the huge Final Assembly Hangar to go out the door and into a nearby paint hangar where they are camouflaged. Working exactly as an automobile assembly line, this mechanized line at Lockheed is notable not only because it is the first continuously moving final assembly line for combat aircraft in the West but, it also does what many experts said couldn't be done by putting twin-engined "Lightnings" on a full production basis. The room shown here was completely emptied of airplanes, which meanwhile were completed on an impromptu outdoor line. In eight days, the new mobile line was set up ready to receive its new quota of airplanes.

Wrap it up and call Fedex! Cocooned Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and North American Aviation P-51 Mustangs line the decks of a US Navy Escort "Jeep" Carrier (CVE) ready for shipment to Europe from New York. Photo by Alfred Palmer/OWI/LOC