ME AND MR. JONES

“If I can walk, I can fly.”

Gordon said this to me when I visited him this past August, as he sat in his easy chair, swollen legs elevated, a warm blanket covering him, still looking like a king, a member of aviation royalty, granting me an audience. Sadly, I could see his flying days were behind him.

When I arrived, I came bearing a lasagne, a fruit crisp, and a kiss on his forehead. “No pie?” he asked.

“No, no pie.”

His mouth displaying a disappointed grin, he raised his eyebrows up quickly then let them drop.

The first day I met Gordon face to face, I brought him a lemon meringue pie. Little did I know how much he liked pie. Over the past two years and dozens and dozens of interviews, driving from Calgary to High River, Alberta and back, I discovered how much Gordon liked fresh homemade baking, how his mother made him pies when he would come home on leave as a student pilot and then from his instructor duties with the RCAF during the Second World War. His daughter, Mary-Ellen, told me, “Anne, when you brought that first pie, you were ‘in’!”

Gordon would call me up as the months progressed and say, “Anne, I’ve got another story to tell you.” And down I would go, laden with cookies, cheesecake, or brownies and cinnamon buns, or a lemon loaf... but his preferred dessert was a pie... any pie would do, although he had his favourites.

One of the last times I visited with Gordon was just after he had been moved to the Okotoks Hospice. I brought a berry pie. “I’m not all that hungry,” he said. Later, I was told he had a few bites in the afternoon, telling the nurses happily, “It’s Saskatoon! It’s Saskatoon!”

Baking for Gordon and collecting his stories became a comfortable routine. I was on the hunt for tales for a fictional story I was writing about a boy from a small town in southern Alberta who became a pilot; the backdrop: The Great Depression and the Second World War.

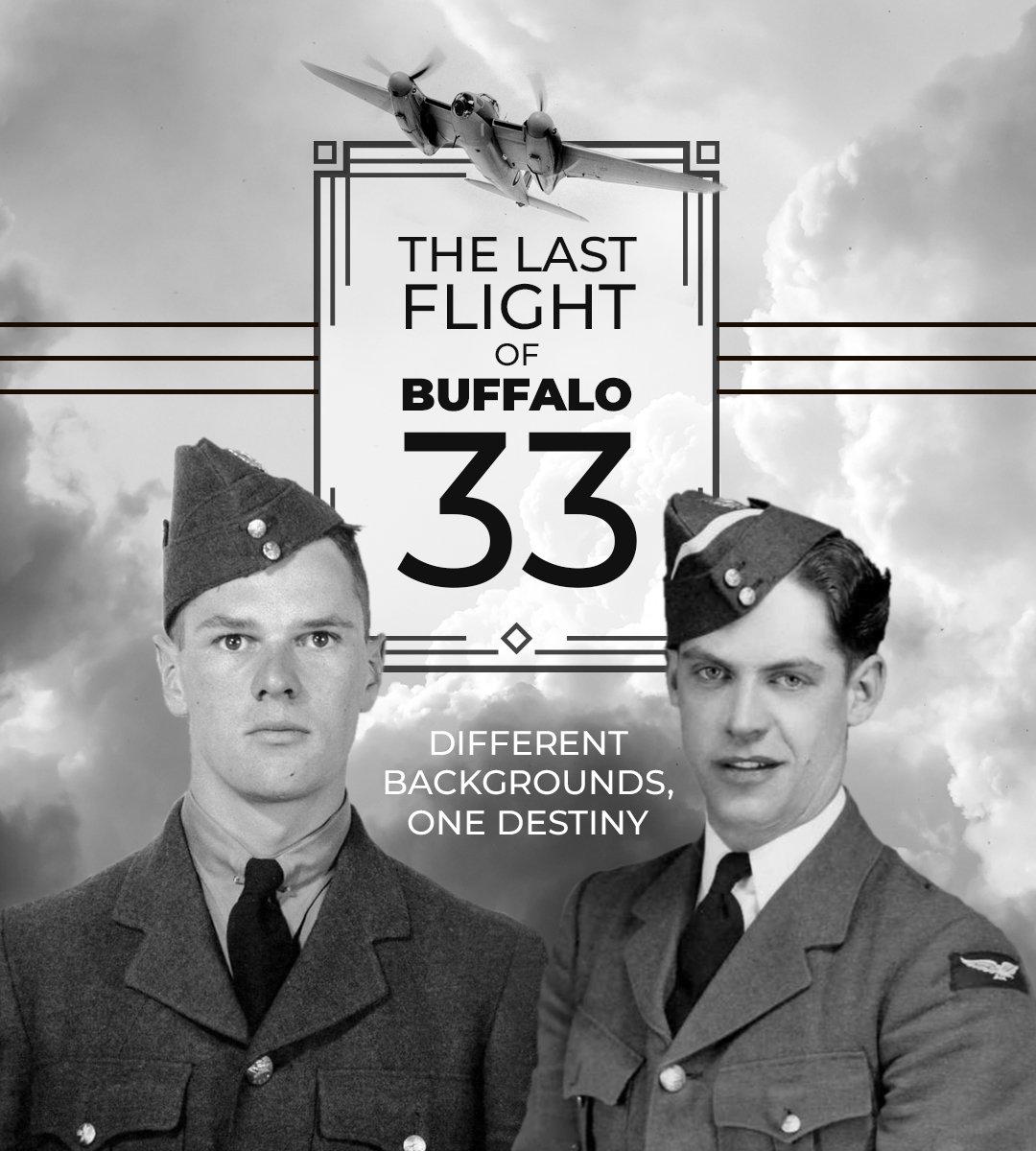

Newly-winged Pilot Officer Allister Gordon Jones in his formal portrait as an instructor pilot with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Photo: Gordon Jones Collection

A late war photograph of Pilot Officer Gordon Jones speaking with the Governor General of Canada, His Excellency the Earl of Athlone during a vice-regal inspection visit to No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School at High River, Alberta later in the war as indicated by Jones’ service ribbons. Accompanying the Governor General were Air Vice-Marshall G.R. Howsam (foreground), a First World War fighter ace of the Royal Flying Corps with 13 confirmed victories. RCAF Photo via Gordon Jones Collection

I first saw Gordon Jones—actually his airplane—in July 2011 at the Claresholm, Alberta airport. (At the time, I didn’t know Claresholm had an airport. I had no idea there were so many little airports across the country because of the Canadian war effort.) There were the five yellow airplanes parked there, all part of the Vintage Wings of Canada Yellow Wings Tour that summer which had flown over the Bomber Command Museum in Nanton a few hours earlier. I hit the brakes, and with my mother, aunt and two of my children with me, put my SUV into reverse, backed up and drove into the parking area. I couldn’t believe my good fortune.

As my children and I milled around the old aircraft, one pilot from Vintage Wings asked my daughter, “Would your mother like to sit in my airplane?” What a thrill! My children also had the opportunity to climb into the aircraft for a photo op.

Related Stories

Click on image

The author Anne Gafiuk posing happily in the cockpit of the Vintage Wings of Canada Cornell, dedicated to the memory of Flight Lieutenant Archie Pennie, like Gordon Jones, a long-time EFTS flying instructor of No. 4 Training Command of the BCATP.

My aunt and my mom, in the meantime, were reminiscing about these old airplanes; they grew up in the 1940s east of Carstairs, Alberta. The aircraft used to come in flying over their farm, the distinctive sound of the engines heard before they were seen. After further discussion, I found out my eldest aunt was a stenographer at No. 4 Training Command Headquarters (TCHQ) Administration Unit for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) on the 6th floor of The Hudson’s Bay Company department store in Calgary!

We posed in front of a few more airplanes, then saw the pilots and planes readying for departure.

One particular airplane caught my eye. I watched as a man, who must have been at least 80, climbed into the cockpit, then watched him fly away, my daughter capturing its takeoff on her new iPad. I thought the man was too old to be flying and he looked like a farmer. I joked with my family: “The headline in tomorrow’s Herald is going to read: Senior Absconds with Vintage Aircraft—Lands Safely in Airdrie.”

Author Anne Gafiuk and her children pose with Gordon Jones’ Tiger Moth (RCAF Serial 1214, Canadian registered CF-CIX), one of the many Tiger Moth trainers he actually flew as an instructor at High River, Alberta. Gordon Jones is standing over Gafiuk’s left shoulder. Jones’ de Havilland Tiger Moth was originally one of 200 ordered and built for the United States Army Air Corps, designated PT-24 DH (Serial Number 42-1078). Then it was listed as a Lend Lease aircraft with RAF serial number FE214 and then sent to High River as RCAF 1214. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

Pilots of the Vintage Wings of Canada Yellow Wing tour of 2011 at Claresholm, Alberta pose with Gordon Jones. Left to right: Dave Maric, Liam O’Connell, Ron Dujohn, unknown, Bruce Evans, Ulrich Bollinger and Gordon Jones. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

I contacted Nanton a few days later and asked who that elderly pilot was. Matter-of-factly I was told, “Gordon Jones,” like I should know. I asked if they thought he might talk to me about his experiences for a story. “Absolutely!”

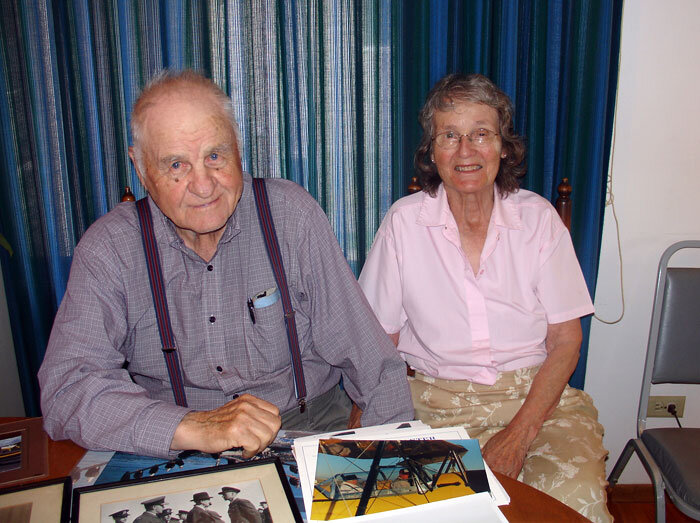

I cold-called Mr. Jones on a Wednesday, talked with him for an hour, and by Saturday, I was in his living room, interviewing him and his wife, Linora, about their wartime experiences.

Gordon Jones, then 88 years old, and his wife Linora in High River, August 2011. Photo: Anne Gafiuk

It was on this day I had the privilege of riding with an 88-year-old pilot, a former BCATP Pilot Officer from the Second World War in his Tiger Moth, one he flew as a nineteen-year-old instructor out of No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) in High River!

It was the beginning of a relationship and journey, learning about a chapter in Canadian history I knew nothing about. I had no map to help me along the way, but I had found a guide who took me by the hand and walked me through his life—as a teenager to being a 90-year-old who still flew an airplane.

Directors at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada caught wind of my interviews, and approached me to write a book about Gordon. The fictional story had to take a back seat.

The author, Anne Gafiuk, about to take her first Tiger Moth and open cockpit biplane ride at High River, Alberta with 88-year-old Gordon Jones at the controls. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

The view over Jones’ beloved Tiger Moth 1214 as they climb into the skies over the QEII (Highway 2), the longest Provincial highway in Alberta. Photo: Anne Gafiuk

Gordon’s biography, Wings Over High River, captured the interest of many people—from within his own community of High River, straight across Canada, into the United States, over to England, Pakistan, Slovakia and Australia. His story found its way into online features, newspapers, magazines, and was broadcast on CTV and CBC, including The National with Peter Mansbridge, with Gordon up in the skies flying Tiger Moth 1214.

Gordon continued to call. “I remember another story.” So I loaded up my camera, tape recorder, notepad, and baking. I started to wonder if it was not the baking bringing out the stories! I enlisted the help of my friend, professional photographer, Don Molyneaux, to take pictures of the Jones’ photo collection, plus come up with originals, making Don an integral person to the telling of Gordon’s story.

One bright and early morning in October 2011, Don and I drove down to High River. Gordon was waiting, raring to go. We made our way out to the High River Airport and set up the equipment just as the sun was rising. We pulled Tiger Moth 1214 out from its hangar and Don started working his magic. “Turn this way. Turn that way. Chin up, chin down.” Gordon obliged. “Put your hand in your pocket, on your hip.”

I teased Gordon afterwards, “Well, to your resumé of pilot, farmer, rancher, businessman, and politician, we can now add: model!”

In 2011, the sun rose over the High River prairie in much the same way as it did when Gordon Jones instructed there during the war. Now, seventy years after first flying a Tiger Moth, Gordon Jones still struck a powerful and proud pose beside his beloved flying machine. Photo: Don Molyneaux

By November 2011, Gordon’s military records arrived by post from Ottawa. “Boring,” he said, after a luncheon at the Aircrew Association at Calgary’s Mewata Armoury. They may have been boring to him; to me, it was anything but, as I was soon to discover.

Gordon told me many tales; I knew there were others he was not going to share. He only told me what he wanted me to know. He was a man of few words, really. His eldest son said, “Dad trusts you.” I felt honoured.

Author Anne Gafiuk and Gordon Jones going over a draft of Gordon’s biography in January, 2012. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

Gordon invited me to the High River Legion a few times, as well as brought me to a couple of Flying Farmer functions and a fly-in, introducing me as his girlfriend, his blue eyes shining with that cheesecake smile to go along with it. He had other nicknames for me: secretary, biographer, “the woman writing my story”, and social coordinator.

He set me up with many aviation enthusiasts, too, unbeknownst to him. In order to confirm his record of flying a Tiger Moth for seventy years, I talked to people across Canada. In researching the BCATP, I encountered special interest groups relating to vintage aircraft as well as RCAF memorabilia collectors. And the most wonderful thing about it? They wanted to help. If they did not know of someone who had the answer, they referred me to someone who might and often did.

Interviewing more veterans of the Second World War, I learned about the type of airplanes they piloted or flew as crew members in: the Harvard, Spitfire, Lancaster, Stearman, Stirling, Mosquito and the Tiger Moth, plus I met one Merlin engine mechanic who witnessed D-Day action. For good measure: a couple of sailors, all because of working with Gordon.

By listening to their stories, I was able to glean a better appreciation of what Canadians did during the war. I read books, realizing how the BCATP affected Canadian families in some capacity, whether it was sending their sons, nephews, uncles, fathers, fiancés or husbands overseas, or helping with the war effort here at home.

A typical graduating class from No. 5 EFTS High River—Course 92, “E” Flight. Photo via Anne Gafiuk

The last of two original hangars of No. 5 EFTS, High River, now houses equipment and storage of a home building company. Photo: Don Molyneaux

Inside the more than 70- year-old hangar, the wood structure looks in relatively good condition. Photo: Don Molyneaux

Heading to Ottawa for research at Library and Archives Canada, I delved into some of the men’s files—those who never returned. They were part and parcel of the stories I heard. When I came home and shared what I discovered with two of Gordon’s friends, they said, “Anne, I’ve been waiting seventy years to find out what happened.”

The author was able to travel to Ottawa to conduct records research at Library and Archives Canada on a number of stories related to Gordon Jones. She was able to bring back to Jones the stories and fates of some of his classmates from his own training days at No. 5 EFTS High River and No. 7 SFTS Fort Macleod. At left is Flight Lieutenant Ian Lorne Colquhoun, 22, of Edmonton, Alberta. Colquhoun was an RCAF Halifax pilot. He was killed in action on 18 August 1943. He was the pilot of Halifax DK260 pf 434 Squadron which was shot down over the rocket research base at Peenemunde. Colquhoun is buried in the Berlin War Cemetery in Charlottenburg, Germany. He had a small creek near Wembley, Alberta named in his honour after the war.

At centre is Flight Lieutenant Leslie Norman Laing of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, an Avro Lancaster pilot of 405 Squadron, a Pathfinder unit with 8 Group. Laing did his EFTS flying at No. 15 EFTS Regina and No. 4 SFTS Saskatoon, close to his home. Like Gordon Jones he went to Central Flying School at Trenton and then on to High River as an instructor (likely where he met Jones). He also taught at No. 15 SFTS Claresholm and then went on to operational training and squadron deployment. Laing was shot down and killed on 15 March 1945 on his 35th sortie, only a month before 405 Squadron flew its last operational mission of the war. It is possible that he, along with three other members of his crew were shot while trying to evade capture. He is buried in Germany at the Hanover War Cemetery and was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches in the London Gazette in 1946. Lake Laing, NWT is named in his honour.

At right is Flying Officer Robert Warren Conway, 26, of Montréal, Québec, who died just five days after Colquhuon. Records indicate that he went to No. 12 EFTS Goderich, Ontario, then to No. 31 SFTS Kingston and as Warrant Officer Robert Warren Conway was taken on as a student at No. 34 Operation Training Unit (RAF) at Pennfield Ridge, New Brunswick, flying Lockheed Venturas from January to April of 1943 with a deployment to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. He died on 23 August 1943 when his aircraft (possibly a Blenheim or Whitley) was seen to dive into the Severn River (he was based at RAF Ashbourne) while on a night flying training flight at No. 42 OTU. He is buried at the Bath Haycombe Cemetery in Somerset, England. His service records indicate he was at the Central Flying School at Trenton but not at the same time as Gordon Jones, but was posted before examination. Photos via Library and Archives Canada

I travelled to Victoria to interview Gordon’s friend, Bob Spooner, gaining further insight into the life of an instructor, gathering up a few more stories along the way about Gordon and his buddies at No. 5EFTS. When we were discussing accidents, Bob said, “The bottom line: they were not doing what they were supposed to be doing.” Ah... and the lucky ones? They got away with their lives and not just overseas, but here in Canada, too!

Travelling with Gordon and Linora and their cousins to Hanover, Ontario, Gordon was the recipient of the Canadian Owner Pilot Association (COPA) Award of Merit. He had the option of receiving the award closer to home, but he said, “I want to be where there are the most people.” His pilot’s ego was coming through, even at 89 years of age.

After the book was published in December 2012, I teased him, “I am not done with you yet.” His homework included signing his name on the inside cover of the book beside his picture. I had hoped, too, to ask him his opinion and insight into the new projects I had started: letters of RCAF personnel during WWII and an Accident Proneness Report, amongst others. Regrettably, that did not come to pass. Gordon’s health was starting to fail.

A photo of friends in 1943—the “High River Clan” of instructors and their wives: Ralph and Lois White, Ernie and Goldie Snowdon, Bob and Marie Spooner, and Linora and Gordon Jones. Photo via Gordon Jones Collection

De Havilland DH82 Tiger Moth, serial number 5091 spun and crashed after takeoff at 20:00 hrs, on 13 May 1942. The aircraft came down 5 miles north of High River aerodrome. One of Gordon Jones’ fellow instructors, Flight Sergeant Phillip Hayne Chapman was killed and his student, LAC R.B. Thompson seriously injured. The accident reports states: “A/C took off with Sgt. Chapman in front seat giving instruction to LAC Thompson. Shortly after a/c made a gentle turn to the right then went into a spin to the right and continued to spin until it hit the ground totally damaged. Propeller was not turning when a/c crashed. Though injured, Russell Bennett Thompson, of Winnipeg, went on to complete his training and to join 158 Squadron as a Pilot Officer. Sadly, he lost his life on the night of 2–3 June 1944 on ops to the French city of Trappes, southwest of Paris. He is buried in the Ecquetot Communal Cemetery in the town of Eure.” Photo via Museum of the Highwood, High River, Alberta

Gordon Jones would attend more than a few funerals like this one for students and instructors. While at Flying Instructor School at Trenton, two of Jones’ friends, Pilot Officer George H. Armstrong of Gananoque, Ontario and Pilot Officer Harry K. Robertson were killed in a Harvard he had just flown that morning (Harvard No. 3102). Photo via Museum of the Highwood, High River, Alberta

Mr. Allister Gordon Jones opened up a new world to me.

Having now immersed myself into the vintage aviation culture and WWII pilots, I want to learn more about their experiences as individuals, not only as a group of pilots, navigators, wireless operators, gunners and mechanics. What did they think about, feel, experience? I have only scraped the surface, but I have been welcomed and encouraged by many, Gordon being the conduit to this multi-layered area of aviation history in Canada.

Me and Mr. Jones...

Thank you, Gordon, from the bottom of my heart.

On 10 September 2013, at the age of 90, Allister Gordon Jones passed away. An estimated five hundred people came out to pay homage to Gordon ten days later at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta where Gordon’s Celebration of Life was held. The Canadian Legion also participated in their touching Tribute, laying poppies on a cross, commemorating Gordon’s time in the BCATP and the RCAF as a pilot instructor.

When I visited him in the hospice, a week before he died, I held his hands and told him I might have the opportunity to fly in a Harvard—his favourite airplane. He whispered, “Do it!” His eyes as blue as ever seemed to take on a little bit of extra light, as he remembered his love affair with flying.

As Gordon’s funeral procession made its way up the QEII Highway from Nanton to the High River Cemetery, a restored Tiger Moth followed along, after it had thrilled those still at the BCMC on 20 September, with a few flypasts. Pilot Doug Robertson, from Black Diamond, honoured by the request to accompany a fallen fellow aviator, continued on above the cemetery, for a fitting tribute. “Gordon Jones has flown west.”

Fly higher than the sky, Gordon... Per ardua ad astra

Pilot Officer Gordon Jones as a Cornell Instructor at No. 5 EFTS High River. Photo via Gordon Jones Collection