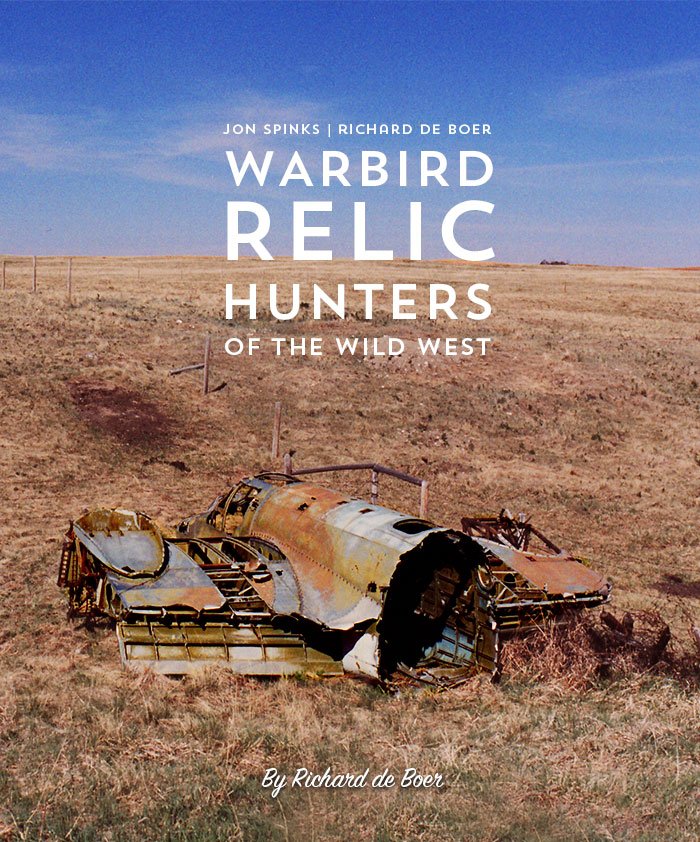

BITTEN BY A MOSQUITO

In the summer of 1964, as a young fellow of 16, it was commonplace to come in contact with one of nature’s more disagreeable manifestations, especially when fishing with my grandfather. But, on one hot summer day, I encountered a never-before-seen species. It was huge! Its body was 44 feet long and its wings, 54 feet. It even sported two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, making it one of the fastest creatures in existence. Yet where did it come from? As an aviation devotee, until now, I had never seen such a winged predator. Obviously, something had been missing in my all aviation “upbringing”, and it took a trip to a local movie theatre to observe what I had been missing. Now, in a darkened theatre, I had been bitten… by winged actors in a new movie entitled 633 Squadron.

They were de Havilland MOSQUITOS!

Having grown up in the U.S. in the late 50s and early 60s, especially in the somewhat serene Midwest, my exposure to Second World War aircraft had been limited to fleeting appearances during the “late-late show” where I might see B-25 Mitchells in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, or even possibly an Avro Lancaster in The Dambusters. In those days, there was no way to record anything, and the images I had seen were always in black & white, with the chance of seeing anything twice a real hit-or-miss process. Even the local hobby shop carried airplane models that had more of a local appeal and at that time air shows in my part of Michigan were pretty much non-existent. On that fateful Saturday afternoon, I decided to kill a few hours and walk downtown to see a movie, expecting to see a farcical tale involving Robert Goulet and Robert Morse, and of course, some incredibly beautiful girls in bikinis. Sadly, the girls were OK, but the film was a dud. Then, all of a sudden, a trailer for the coming attraction grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. Out of the theatre’s darkened silence, emblazoned across the screen was the statement, “Courage is the crucible in which the shape of greatness is forged…This then is a story of courage… The story of the men of 633 Squadron. “THE WINGED LEGEND OF WWII.” ” Really? Was this real or fiction? Then, with a background montage of aircraft dodging anti-aircraft fire appeared the words, ATTACK! ATTACK! ATTACK! No matter how many men were killed… No matter how many planes were lost… Theirs was the mission that could not fail! With a “pull back” widescreen shot of water and a mountainous horizon, there appeared three Mosquito aircraft barely skimming the waves at top speed, now advertising: The Mirisch Corporation presents 633 Squadron. Wow, from out of the blue! I never expected this. Here, in the middle of a hot Michigan summer, I felt like a kid on Christmas morning.

One sheet posters for 633 Squadron heighten the drama of the already dramatic plotline. Five Mosquitos in trail squeeze themselves into an impossible crevasse while pilots embrace blondes and deal with flaming events—so typically 1960s. The purple prose that accompanies the images is even more over the top—The greatest adventure since men fought on Earth... or flew over it! ... A million legends have risen up about the lusty, daring breed of raiders known as 633 Squadron... as the Earth is engulfed in titanic battle... 633 Squadron strikes! Images from author’s collection

633 Squadron won wide acclaim for its drama and authentic flying sequences. These posters reflect its international appeal (clockwise from upper left): Mission 633 (France), Escuadron 633 (Spain), Squadriglia 633 (Italy), Zadatak Eskadrile 633 (Yugoslavia-Croatia) and Flyver-Eskadrille 633 (Denmark). Various posters from the internet

Related Stories

Click on image

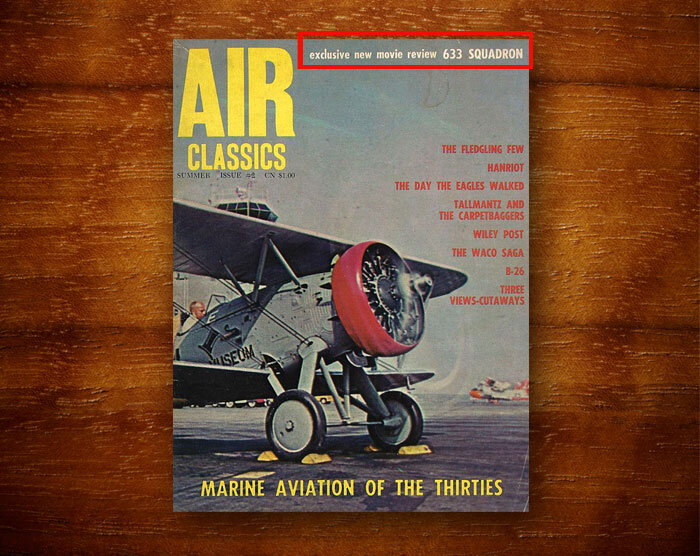

Now thoroughly intrigued, I persevered through that boring movie two more times just to see that exciting trailer, again and again. Oh I was hooked; by the story, by all the aircraft, and as a musician, by the machine gun staccato film score. As I left the theatre, my thoughts went to these marvelous heretofore unknown (to me) airplanes and the story behind them. And was there a real 633 Squadron? Where did they come up with these aircraft? I had to know more, which then required a walk to the other end of town to visit the best bookstore I could find. There on the top magazine rack, was a brand new publication, Air Classics Issue #2. Across the top, as if by my wishful thinking, was printed, “Exclusive new movie review – 633 Squadron”. I was off to the races. This magazine article fuelled a new passion for said Mosquito, and I had to know anything and everything about the story, the aircraft and the movie.

The actual cover of the Air Classics magazine issue that featured a review of 633 Squadron and the flying done for the film. Image from author’s collection

I had always been a fan of history, especially anything having to do with planes, trains and submarines. Being an aficionado of Warner Brothers’ The Spirit of St. Louis (1957), Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and The Great Locomotive Chase (1956), I now had a new desire to dig and find out all I could from this marvelous film, just as I had done with the previous three films. And that ardor from my youth has not slackened to this day. That’s why, Reader, this mosquito bite has lasted for five decades. I have always loved to discover details that might have been overlooked, as there is always a story within a story, especially when it comes to using “period” trains, boats or airplanes as stand-ins in front of the camera. Aside from a movie tale, on their own, they all had a personal story to tell.

Following a week of anticipation, that next weekend, I had a game plan. At that time, when it was possible to stay through multiple showings, I bought my ticket and sat through the entire movie, three whole times. I tried to absorb all I could visually and to listen and even memorize the unforgettable opening rhythmic intro of the Ron Goodwin soundtrack. What was the next step? I found and read the Signet pocketbook copy of 633 Squadron, then wrote to the publisher so I could get author Frederick E. Smith’s mailing address in England. Then, I wrote a lengthy letter to him, full of questions and commentary as to the differences between the film and his original book. It took some time for an answer, as he had been in an accident, but Frederick wrote a gracious and very long letter back to me, more than a year later; and it was worth waiting for. He answered every one of my questions, from the novel’s dedication to his thoughts on the Mirisch Corporation’s handling of the book versus the movie.

From his letter, dated 26 January 1966, Frederick E. Smith answered:

“I served for six years in the R.A.F., from 1940 to 1946, and the book [633 Squadron] was intended to be my tribute to the service and my friends, a number of whom, unhappily, were killed.

Not, however, the two in the dedication. One, Bob, is now a salesman, and the other, Des, after being the only survivor when his Liberator [B-24] received a direct hit from flak over Naples and later surviving the Polish Death March, is now something of a business tycoon. Des, I think, is indestructible!

No, I can’t say I ever served in Norway. Deciding that I could best bring out the character of these men I had known in a fictional work, I obtained permission from the British Air Ministry to use the squadron number 633 (one of the few below 700 that had not been used during the war) and then, using a target in Norway as my goal, I set about reconstructing the story as realistically as possible. I feel I can vouch for the authenticity of the squadron atmosphere, for the technical details and also for the air actions, for some of these were actual fights simply transferred to the Norwegian locale.

It has always been something of a fetish with me to get my facts right for novels and in this case it led me to two trips to Norway and even to check with the German Government that their fighters in Norway were not using a special chemical boost in their gasoline at this time. (Otherwise the reconnaissance Bergman and Grenville made over the fjord would not have been possible.) The answer came back no – it arrived two months after the date in the novel!

If I might be forgiven for mentioning this, it has always been a matter of satisfaction to me shortly after the novel was published, Douglas Bader wrote to me to say that he seldom read war novels, he and his wife liked this one ‘enormously’. The point I am making, of course, is that he found it technically accurate.

No doubt you will have seen or heard about the film your Mirisch Film Corporation made of the novel. Although I thought they did the flying sequences brilliantly – very little of this was faked – I was sorry Gillibrand was relegated to such a minor role, for to me he was a most important (and real) character.”

He closed the letter with “if I would care for it, I would be happy to send you a British version of the novel, autographed and also autographed by two of our Bomber Command’s V.Cs.” They turned out to be Norman Cyril Jackson, V.C. and William Reid, V.C. In addition, appeared one more signature; former RAF Group Captain, Hamish Mahaddie. With his vast military knowledge and connections, Mahaddie had been the technical advisor and man who “wrangled” the Mosquitos for 633 plus all the aircraft for the 1969 film, Battle of Britain. So, of course, that was a given! Each of those gentlemen’s autographs represented a hero in his own right. To this day, they all deserve more stories written about their individual lives and exploits.

633 Squadron author Frederick E. Smith (inset) sent the author a personalized copy of his novel in paperback form, autographed by himself and three rather famous airmen of the Second World War. At top is the autograph of Warrant Officer Norman Cyril Jackson, VC, who received the Victoria Cross for an act of astonishing bravery and determination. As a Flight Engineer on a 106 Squadron Lancaster, he was on the first op of his second tour of operations, when his aircraft was attacked by a night fighter which set the starboard inner fuel tank on fire. Wounded by shrapnel and donning his parachute, he grabbed a fire extinguisher and stepped OUT onto the wing of the Lanc whilst it was still flying at 140 mph. Gripping the air intake on the leading edge with one hand, he fought the fire with the other, receiving severe burns to his face and hands. The fighter made another pass and burst of machine gun fire. He was hit by two bullets, and lost his grip, being swept off the wing. Despite a smouldering parachute, he managed to land, but broke his ankle in the process. Surviving members of his crew were able to tell his story after release at the end of the war. In green ink on the side is the autograph of Flight Lieutenant William Reid, a Scotsman, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his utter determination to press on despite extensive damage to his Lancaster and injuries to himself and crew members. The last line of his citation accompanying the award sums it up very well: “Wounded in two attacks, without oxygen, suffering severely from cold, his navigator dead, his wireless operator fatally wounded, his aircraft crippled and defenceless, Flight Lieutenant Reid showed superb courage and leadership in penetrating a further 200 miles into enemy territory to attack one of the most strongly defended targets in Germany, every additional mile increasing the hazards of the long and perilous journey home. His tenacity and devotion to duty were beyond praise.” The autograph at the bottom is that of the legendary Hamish Mahaddie, DSO, DFC, AFC, a Pathfinders Force pilot and “wrangler” of the aircraft in 633 Squadron and Battle of Britain. As a young lad in Michigan, receiving such a remarkable gift in the mail would have been a powerful and formative moment in his life. Images from author

Some 45 years later, by way of a copy of his original letter of response, I rekindled a friendship with Frederick. Until his death at the age of 93 in 2012, we corresponded a number of times, and were working together in order to finalize the rights to a film sequel of 633 Squadron. We had hoped to get a screenplay into the hands of an agent in the United States, and also, his remaining novels, all the later exploits of 633 Squadron, finally printed in this hemisphere. Sadly, with his passing, there was no one to continue those efforts for him, and the project is on indefinite hold, and will probably be shelved. If I could find any family contacts in the UK to continue, I would be thrilled to make those things happen for his legacy.

There are a number of folks over the years (including myself), who have viewed countless other films (including 633) many times, and have tended to gauge some “seeming” production inadequacies based on today’s movie making standards. Yet, consider this. There have been decades of progress in movie production techniques that were totally non-existent in the 1960s. When the film hit theatres, Ford Motor Company had not yet introduced the first Mustang; there were no computers and thus, no movie CGI effects. Texas Instruments didn’t even have calculators on the market yet! 633 Squadron was a milestone and the first of its type, using “real” action and live camera work whenever and wherever possible. With 633, as director, the late Walter Grauman stated, “I’m sure there are going to be some wise-guys who will look at 633 Squadron and say that we took the easy way out and just raided the old news reel photo files. I suppose in a way that would be a compliment.” Since this was the first aviation film to be shot in color and Panavision widescreen, “That decision automatically ruled out any use of stock newsreel footage, so if the combat mission sequences in our picture are exciting and have a life-and-death look about them, it’s because that’s what we had to risk in recreating these moments for the screen. Everything that the audience will see was actually done for our cameras – including crashes into mountains, belly landings, precision bombings, air assaults and strafing missions. It was eerie at times stepping back into a B-25 [camera aircraft],” he explained.

Grauman himself had flown 56 missions in B-25s in the European Theatre of Operations and was the recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross [American DFC], and won the Air Medal eight times.

“Speaking as both a film-maker and a man who was there, it’s a very important part of the total experience. We would take off from the comparative safety of our air bases, look at incredibly beautiful vistas thousands of feet up there – and be facing death a few minutes later. And a few minutes after that, those who survived, would be heading home again. Through those same beautiful skies. The visual counterpoint was startling to us, that’s why we had to make this film in color,” he added.

An excellent cast of actors was selected. Due to the times and movie-making styles of the 1960s, certain actors were selected due to their popularity and not so much for their accurate depiction of certain characters. The three main characters were Cliff Robertson as Eagle Squadron Wing Commander Roy Grant, George Chakiris as the Norwegian Erik Bergman (even with his very Greek appearance) and Austrian actress Maria Perschy as Hilde Bergman, Erik’s sister and Roy’s potential love interest. The remaining fourteen individuals were cast befitting their English/German roles and were, ultimately, quite convincing.

Black and white images of four of the key “driver-looker” (Pilot/Navigator) crews featured in 633 Squadron. These are different than the pairings as written in the novel (many names and nationalities are different). Clockwise from top left: Flying Officer Hoppy Hopkinson, Navigator (Angus Lennie) and Wing Commander Roy Grant, Pilot (Cliff Robertson); Flight Lieutenant Bissell, Navigator (Scott Finch) and Flight Lieutenant Gillibrand, Pilot (John Meillon); Flight Lieutenant Jones, Pilot (Johnny Briggs) and Flight Lieutenant Evans, Navigator (John Church); and Flight Lieutenant Singh, Pilot (Julian Sherrier) and Flight Lieutenant Frank, Navigator (Geoffry Frederick). Production still from United Artists

Using Bovingdon aerodrome in Hertfordshire as a stand-in for RAF Sutton Craddock, ten Mosquito aircraft were assembled as “winged” actors, the real mechanical stars of the film. Two French-built Messerschmitt Bf-108s (substituting as Bf-109s) and one camera B-25 Mitchell with a specially modified glass nose completed the cast. Even the camera plane was given roundels and had its registration number altered so it could serve as an actor as well. According to FlyPast’s MOSQUITO edition, “For the incredible ‘Norwegian’ flying sequences, three civilian registered ‘Mossies’ were deployed to Inverness. Low-level flying through the Highlands provides most of the edge-of-the-seat viewing during the 102 minutes of 633 Squadron. Two ‘flyers’ on loan and operated under RAF auspices were not used for this risky element. Three Mosquitos and parts from the two used for in-cockpit studio sequences were ‘consumed’ during the filming (and sadly, lost to history).” All of the Mosquitos were given period paint schemes, and numbers as would be found with a real squadron. Since all were decommissioned target tugs, only one T3 had a solid nose, with the rest the slanted Plexiglas nose. Five were airworthy, one was loaned for static scenes only, two were incomplete and used for cockpit sequences and three destined to be destroyed in ‘crashes.’

Dummy machine guns were added, tug paraphernalia removed and the reconnaissance slanted noses were painted over as to resemble earlier production FB.VI Mosquitos, totally changing their current T.T. 35 configuration. For years, in watching countless viewings, I tried to match the numbers of all the aircraft but never quite managed to get them right compared to the number of aircraft. Now I know why it couldn’t be done. For the purists in the audience, and those who ever wondered about the numbers and registration on individual Mossies, here is the breakdown, courtesy of the FlyPast MOSQUITO publication, on the individual aircraft. The first number is their original serial number, then the actual film operational serial number, and the movie fuselage registration code. This will explain why it was impossible to keep track of the number of flying aircraft and corresponding registrations. (In fact, in some instances, one code was painted on one side and another on the opposite.) As one who has been in the film business as an actor, tricks of the camera can create the illusion of multitudes of aircraft when only a few are actually present in the shot. Three aircraft become six, then twelve with a film overlay. (Mosquito RS709 became HR113 as HT-D and HT-G, RS712 became RF580 as HT-F, RS715 was used for cockpit scenes, RS718 became HJ898, HJ662 as HT-C scrapped in crash scene, TA639 became HJ682 as HT-B, TA719 became HJ898 as HT-G, TA642 became HX835 scrapped in crash scene, TA724 scrapped in crash scene, TJ118 was used for cockpit scenes, TV959 became MM398 as HT-P (static) and TW117 became HR155 as HT-M).

A detail from the film shows the altered nose of one of the Mosquitos flown in the film. The angled Perspex nose window of the Mosquito TT Mk35 (target tug) was painted over to make the ship appear to be a different type. The TT Mk35 Mosquitos were RAF target tugs and were the last operational Mosquitos in service with the Royal Air Force, flying with No. 3 Civilian Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit (CAACU) at RAF Exeter. After retirement, they starred in 633 Squadron. Screen capture from United Artists

One of the aircraft destroyed in 633 Squadron crash scenes was TA724, a former Target Tug Mosquito TT Mk35 from No. 3 CAACU. Here we see it in better days at an air show at RAF Biggin Hill in 1957. Photo by a young Peter Arnold

A screen capture from 633 Squadron showing the nose of a TT Mk. 35 Mosquito painted over to hide its Perspex nose and with the addition of fake quad machine guns. Screen capture from United Artists

A 633 Squadron Mosquito low over the sea. Note the painted over Perspex nose and false guns. Screen capture from United Artists

A black and white production still from 633 Squadron shows painted on bullet holes stitched across the engine nacelle and the tail of a de Havilland Mosquito (RAF serial No. RS709) playing the part of 633 Squadron’s HT-D (fake RAF serial No. HR113). Though these holes look faked in this shot, during the film, they were glimpsed very briefly and looked authentic. Production still from United Artists

A 633 Squadron Mosquito crew inspects the damage to their aircraft after landing. This aircraft was the real-life Mosquito (RAF Serial No. RS718) which played the part of two aircraft in the filming—HJ898 and HJ662 (HT-C) and was scrapped in a crash scene. Production still and screen capture from United Artists

One of the RAF aircraft that took part in the filming of 633 Squadron was TA639, which was taken on strength at No. 3 CAACU in September 1959. It flew there irregularly until it was flown to the Central Flying School at RAF Little Rissington with its target towing equipment removed. It was then loaned to Mirisch Films for flying in 633 Squadron. When filming moved to the Scottish Lochs, based at Inverness, the RAF would not allow TA639 to be used since the flying there was considered too dangerous. TA639 was used extensively for filming up to mid September, being at Tern Hill as late as 14 September 1963. After filming was complete, TA639 returned to Little Rissington for personal and display use by the base Commandant, a Air Commodore Bird-Wilson (who incidentally did the flying in it for 633 Squadron), and made one display flight over the Mosquito Museum at Salisbury Hall. After a period of storage, it was given to the RAF Museum. At one time in 1968, it was on static display at the Horseguards Parade near the Mall in London. It is now displayed at Cosford Aerospace Museum as the 627 Squadron Mosquito Mk XX in which Group Captain Guy Gibson, VC was killed in September of 1944. Photo: Wikipedia/Ozz13x

Mosquito RS712 was another 633 Squadron flyer that still exists today. It was a flying star in both 633 Squadron (as RF580/HT-F) and the later (and much lesser) imitator—Mosquito Squadron. It was acquired by Kermit Weeks in 1981, and registered N35MK, and obvious nod to its designation as a Mk 35 Mosquito. It is now on static display at the EAA museum at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Photo via Brendan Deere

Mosquito TA719 also starred in 633 Squadron, playing the part of HJ898/HT-G. It also played a bit part in Mosquito Squadron, used for ground and crash scenes. It is now on display in its Target Tug markings and hanging from the ceiling of the Imperial War Museum’s Airspace hangar at Duxford. Photo via sonsofdamien.co.uk

As a legacy of modern film history, one of the most famous fans of this film turned out to be none other than film maker George Lucas. Lucas literally lifted the scenes of aircraft flying down a valley into the mouth of death, and revisited that sequence into his original Star Wars with the X-wing Starfighters and the Millennium Falcon dodging anti-aircraft fire in his space age “updated” version. Another very interesting “note” for those who have some knowledge of music, and indeed, opera—Ron Goodwin’s film score, aside from the mesmerizing repetitive triplet figure that was used to simulate machine gun fire, dipped into music history (and found in many other parts of the score) actually duplicated Wagnerian opera, emulating Richard Wagner’s The Ride of the Valkyries. This was perfectly fitting as the mythological Valkyries would swoop down from their mountain top and take up their fallen Norse warriors to Valhalla. I would wager not too many might have picked up on that, but having once taught music history, that fact literally leaped off the “musical score” page as I studied music theory, composition and opera history.

In a scene inspired by 633 Squadron, producer George Lucas has Luke Skywalker piloting an X-wing Starfighter through the massive canyons of the Death Star in the closing scenes of Star Wars. Image via the author

Another film where Mosquitos played a major role on film, made in Technicolor in 1954, was entitled The Purple Plain, starring Gregory Peck with several RAF Mossies in authentic Far East livery. (A number of RAF staff was on site during the very accurate filming, with some even receiving credit at the end of the film.) The basis of the film focuses on widower Peck as a Canadian pilot and his heroic actions to keep his companions alive following a crash in Burma, reawakening his will to live.

Scenes and poster from another Mosquito feature film The Purple Plain, starring Gregory Peck. It seems the wooden airframe of the Mossie was just too much for producers to resist, for in this film, as they did in 633 Squadron, one was set on fire. Images collected on the web

Later however, in 1969, Oakmont Productions returned to Bovingdon with a very bland offering entitled Mosquito Squadron. The Oakmont “action formula” production style was simply an attempt to make a series of 90 minute action films; with this one using stock footage and unused footage from 633 (on the cheap) in an effort to ride on the “empennage” of a far superior film. Sadly, a number of film clips were obviously lifted directly from 633, inviting drastic comparisons between the two films. The production values of this make it one of the more “forgettable” films, as the plot (in my opinion, as a screenwriter) was flawed. Even the presence of real Mosquitos was diminished as several fake models were used, trailing obvious wires behind as they hurtled toward their demise. Four Mosquitos were used in the filming of this vehicle for David McCallum. One positive note—thankfully, none of the aircraft were harmed or destroyed.

Another real and very informative collection of films and newsreels, however, is available through Campbellfilms.com, entitled RAF De Havilland Mosquitos. Although some of the film is dated and grainy, these six vignettes explore the story of the Mosquito from the very beginning from wood cut down from Canadian forests and made into the plywood necessary for assemblies, to training and actual in-flight photography taken during action-filled operations.

Despite the wild and furious Nazi-busting action promised by the poster and the huge popularity of the brooding David McCallum (Illya Kuryakin of The Man From Uncle fame), Mosquito Squadron was nothing more than a late cash in on the success of 633 Squadron and McCallum’s recent career. Images: United Artists

The History Channel series entitled Heavy Metal – Mosquito Attack is an excellent documentary on the history and development of the Mosquito, with excellent commentary by actual individuals involved in the Mossie story detailing their wartime exploits.

Since almost everyone now has internet access, one can now simply go to YouTube and find a myriad of film clips of not only 633 Squadron, but other films and live action Mosquito clips as well. It is even possible to download the entire movie should you so desire, depending on your locale and the regulatory issues involved. The DVD is also available through a number of venues.

A few further details regarding the phenomenal de Havilland Mosquito. Designed and first flown by Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, it was built much like a model airplane kit, with subsections from various cottage industries providing parts and assemblies. Until this author started doing research on Mosquitos, I was unaware how much of a coordinated Allied effort was involved in the production. Ultra light balsa wood was imported from Ecuador, old growth forests of Western Canada yielded the major share of birch/spruce plywood (the major component of the fuselage and wings), and Hamilton Standard propellers were produced in the United States by Nash-Kelvinator along with Detroit, Michigan neighbor Packard Motors producing the powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. A total of 1,076 Mosquitos were built in Toronto, 212 in Sydney, and the remaining 6,493 in England.

Nash-Kelvinator was an amalgamation of Nash Motors and Kelvinator, a manufacturer of large appliances such as refrigerators. The alliance allowed them to become one of the largest war manufacturers in America—licence building everything from binoculars to radial engines to helicopters. N-K supplied the Hamilton-Standard propellers used on the Mosquito. According to this period advertisement, the propeller made by Nash-Kelvinator for the Mosquito was “an engineering masterpiece – so beautifully machined that a puff of a man’s breath can set it turning.” Image: from author’s collection

Only a handful survives to this day. It is no wonder that actual pilot and star Cliff Robertson took exception to destroying the three Mossies during the filming. I almost got the opportunity to ask him about that at the opening of the EAA Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, but he was whisked away at the last minute to address the crowd. I know that the willful loss of such valuable aircraft always bothered him and I would liked to have heard his personal feelings on the matter. Robertson even tried to purchase one of the Mosquitos as a potential mate to his Supermarine Spitfire after the film wrapped, but somehow during the legal process, his efforts were thwarted.

A production still (top) and a screen capture from the film itself show the real life tragic end to one of the former TT. Mk 35 Mosquitos. Being a “wooden wonder”, the Mosquito burned with lots of camera appeal. Production still and screen capture from United Artists

A 633 Squadron still in black and white depicts Flying Officer “Hoppy” Hopkinson, played by Angus Lennie, pulling an unconscious Wing Commander Roy Grant, played by Academy Award winner Cliff Robertson, from the burning wreck of their badly shot up Mosquito. Production still from United Artists

In the years since then, the remaining “actor” Mossies have found their way into several museums. It should be noted that Mosquito T3 RR299 (G-ASKH), the last of the operational Mosquitos from the film, crashed while performing at an air show at Barton, Manchester, on 21 July 1996, claiming the lives of pilot Kevin Moorhouse and engineer Steve Watson. Since then, following thousands of hours of restoration, two “new” Mosquitos have taken to the skies. Built for the Military Aviation Museum in the U.S., an original 1945 Canadian-built de Havilland Mossie, FB.26 KA114 now wears the color scheme of 487 Squadron, a UK-based RNZAF unit composed of “Kiwi” crews, having been lovingly restored and made totally airworthy in New Zealand. (487 Squadron made history as they took part in the famous raid on Amiens prison on 18 February 1944.) Her appearance has been enthusiastically received by those who have seen her take to the skies at a number of air shows in New Zealand, Canada and the U.S. In addition, last year, a second Canadian-built Mosquito flew its preliminary flights in Victoria, British Columbia after years of restoration.

For many years there were no Mosquitos flying anywhere in the world. But three years ago, in New Zealand, Avspecs completed the restoration of Mosquito KA114, a Canadian-built Mossie. It now flies for the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Photo by Luigino Caliaro

In 2014, a second flying Mosquito took to the skies in Victoria, British Columbia, restored by Victoria Air Maintenance Ltd. It commemorates F-Freddie (with 213 combat missions, Freddie had more ops than any bomber of the war), which was lost in a tragic crash at Calgary airport in 1945, during a victory tour. For more about the tragic and powerful story of F-Freddie click here.

Now, as I prepare to dim the lights and close the doors on the hangar, should there be any interested readers who are model builders as well, I have great news! While there are many smaller scale models (1/144, 1/72 and 1/48) of the Mosquito available in a number of variations, if somehow you missed the first production run of the massive museum quality AIRFIX 1/24 highly detailed scale model of the Mosquito, another run is scheduled to be out on the first day of October 2015. If anyone is interested, (and I am not receiving any commission) direct orders are still being accepted by AIRFIX in the UK. So while I may not near any of the remainder of my favorite full-sized original aircraft, at least my order is on file and I can ponder its arrival here in the States in the fall. And when it does, I will then have a chance to create my own special version of “mechanical entomology,” reminiscing about that first infestation those many decades ago. It goes without saying, in the background of course, 633 Squadron will be replaying on my home theater, and speakers turned to the max! Who doesn’t love the sound of all those well-tuned Merlins (except maybe the neighbors)?

By Doug Deaton

One if the great things about publishing on the web is that the story can reach people you never thought it would. A couple of days after this story went out, we received a couple of letters if interest to author Doug Deaton and editor Dave O'Malley. The first was from world renowned aviation artist and illustrator John Batchelor commenting very positively on the story and another was from Jim Dowdall a film stunt man. Jim described a story of his experience whilst the filming was taking place. He writes:

Hi Dave.

Read the article on 633 Squadron with great interest tinged with a bit of nostalgia.

In the 60’s I was a young movie armourer working on such films as ’The Dirty Dozen’ and Where Eagles Dare’

I also worked on ‘Mosquito Squadron’ looking after the guns.

In those days, I drove an Austin Champ (British post war equivalent of the Willys Jeep) and on the Sunday off after we had finished one of the Mosquito fly past scenes at Minley Manor, I drove over to Blackbush airfield where the Mozzies were based for that particular scene.

As I was in an old military vehicle, I managed to blag my way onto the airfield at Blackbush where the Mosquitos were based for that sequence.

They were about to do a test flight to try the smoke canisters being fitted below the wings to give the impression of the aircraft being hit by flak. No computerised effects in those days…

I got talking to the pilot and engineer as I always had a real interest in WW2 warbirds (my dad who worked in advertising, had the Airfix account and brought me back every 2 shilling aircraft kit and I had the lot suspended from various ceilings around the house).

As I was walking round asking all the usual questions, they said would I like to come up for the test flight. I remember the nanosecond it took to say yes before they changed their minds.

No health and safety stuff in those days! I just sat slightly behind them on a pile of whatever soft stuff they had with them and up we went for ten minutes or so.

The most exciting flight of my life if not the noisiest by far. Absolutely deafening as I had no ear protection at all.

I’d flown in the nose of one of the Spanish Heinkels on ‘Battle of Britain’ as the forward machine guns were giving trouble. They weren’t designed to fire blanks so I got put in a Lufwaffe buff coloured overall and fired at Spitfires over the cliffs near Dover I seem to remember. But it wasn’t a scratch on the flight in the Mosquito.

Having been a movie stuntman now for over 40 years, I’m almost completely deaf as my work has involved firearms and explosives on an everyday basis.

However, I always felt that the flight in the Mosquito was the start of the problem! But what a way to start!

Many years later in the 80’s (with a good disposable income prior to being married….), I bought the original Robert Taylor painting of Leonard Cheshire piloting a Mosquito over Le Havre on the 14th June 44.

I called Sir Leonard at the Cheshire Foundation in London and he very kindly agreed to sign it for me. One of the most interesting hours I’ve ever spent with any ex service person in 50 years of collecting. But that’s another story.

All the best.

Jim Dowdall

The box art for the Airfix 1/24 scale model of the Mosquito, available in October of 2015. Image from Airfix

Like many successful blockbuster films of the day, 633 Squadron inspired some spin-off merchandise like these collector bubble gum cards depicting the heroes and villains of the film. If the film was made today, there would be action figures, McDonald’s giveaways and video games. Images via the author

The plot line of 633 Squadron had the crews attempting a very dangerous attack on V-2 rocket fuel plant hidden deep in a Norwegian fjord and protected by a massive overhanging cliff that precluded high altitude bombing. The inbound flight path took them past heavy anti-aircraft defences similar to these Luftwaffe gunners in the film manning a quad 20 mm Flakvierling cannon. This scene however is from another attack in the film where Cliff Robertson and Angus Lennie’s characters take out a Gestapo HQ where the Norwegian Erik Bergman is being tortured by an “Ilsa-esque” female Gestapo interrogator. Screen capture from film, United Artists

Four of 633 Squadron's Mossies return to base after a training mission. Production still: United Artist