EAT AND GET GAS

First Published April 1, 2014

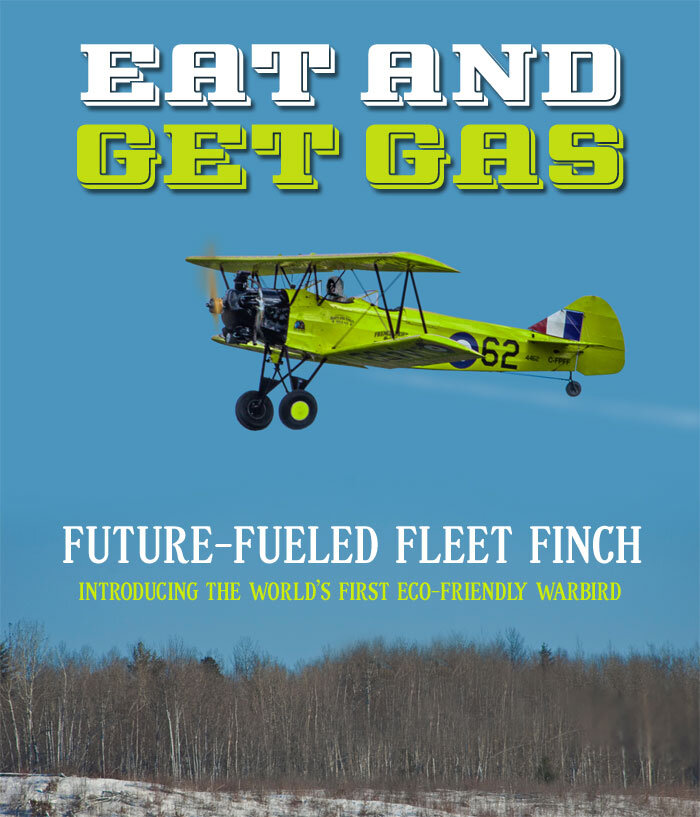

On Saturday 22 March 2014, a new era dawned for warbird operators across the planet when a delicate, lime green Second World War Fleet Finch took to the air in minus 22 degree temperature. Her pilot, George Arborpremo, eased the throttle forward as her tail came up and she clattered down the runway with the sound she always had... not unlike a 1938 Massey Harris tractor. She lifted from the dry runway, climbed up over the snowbanks of the Gatineau–Ottawa Executive Airport, over the bare winter tree line and into the bluest of winter skies. Behind her, in the cold crisp winter air, trailed a pale and delicate plume of whitish blue exhaust that was pushed by the northwest wind gently back towards a cluster of worried Vintage Wings volunteers standing on top of the snowbanks. As the Finch climbed easily to the west, the air around us smelled vaguely of the heavenly scent of french fried potatoes and onion rings. The excited group, Vintage Wings’ Team Future Fuel, hugged each other and slapped high fives to mark a new milestone in green aviation—the world’s first eco-friendly warbird.

After the 2013 Wings over Gatineau Air Show, a group of Vintage Wings pilots had retired to a local chip stand called Casse Croûte Chip Chip Hooray to talk airplanes and eat pilot food—a Vintage Wings post show tradition. Sitting at a picnic table with the sun setting, the conversation worked its way from an air show debrief to flying stories to the looming problem of 100LL Avgas. A recent editorial in the excellent magazine Canadian Aviator, which some sitting at the table described as “flatulence emanating from a certain sector of Canadian aviation”, had just been published, decrying the air show as a fading entertainment unjustly funded by taxpayers, warbird operators as tax avoiders and the most hurtful of all, vintage aircraft as polluters. As they happily munched on their deep fried dinners, the animated group of warbird men had come to the conclusion that it was indeed time to do something about this problem. And the solution was at hand... or at least in the french fries in their hands.

Revolutions begin in the most unlikely places. The first tentative steps toward a sustainable warbird future were taken here at the Casse Croûte Chip Chip Hooray near Templeton, Québec, just a few kilometres from Vintage Wings of Canada.

At Vintage Wings of Canada, we can read the writing on the wall or in aviation magazines as the case may be. Soon, leaded 100 octane aviation fuel, the lifeblood of reciprocating warbird operations around the world, will cease to be available in Canada and possibly the world. Speaking as warbird operators, this day-still-to-come was going to be a sad day, but speaking as environmentally-reborn Canadians, we at Vintage Wings of Canada know we must take full responsibility for the thoughtless environmental devastation we have wrought across our country.

In Canada, with almost 50–75 vintage warbird aircraft, flying an average of 20 hours per year, the toxic output of our nation’s warbirds is roughly the equivalent of an Ontario snowplow operating continuously through this past winter’s record snowfall and sub-zero temperatures. I know it’s hard to believe. It’s even harder to continue to justify. Though our dreams to honour our veterans and inspire our youth to give back to their country are of the highest civic order, we can no longer do it at the continuing destruction of our beloved environment. Thanks to the prodding of inspired and forward looking Future Fuel leaders, we have come to our senses and to a realization that this loathsome and massive output spewing from our exhaust stacks must end, that we must take responsibility and that a solution must be found.

We HAVE been listening. Taking our cues from the bellwethers, the friends of the earth and the golden knights of righteousness, we have a plan to make changes that will benefit not only the Canadian warbird community, but our brothers and sisters in America, Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand. We looked to environmental stalwarts and centres of excellence like China and Russia, where vintage warbird operation has been all but wiped out to reduce the pressures on their environments. It’s no coincidence that these, the most environmentally forward of nations, have no warbird community to speak of. In these countries, the first things they addressed in their well-conceived environmental programs were warbird aircraft operations and gas-driven amusement park rides in the outlying provinces. When these scourges have been eradicated, their focus will no doubt turn towards lesser problems such as industrial smog, transport and automotive pollution, the dumping of heavy metals into drinking water and such.

For years, the warbird-industrial complex has ignored the elephant in the room—toxin-emitting warbirds are killing our planet. Air shows, though honourably intended, are no better than Soviet-era nuclear dumping grounds, Bangkok traffic jams or the electronic waste dumping capital of the world, Guiyu, China. Zhong Nanshan, the president of the China Medical Association, warned in 2012 that air pollution caused by Canadian pilots over-priming their engines on start-up scored the highest of environmental worries for China’s citizens. “End the over-priming problem”, says Nanshan, “and China will follow suit with tougher environmental standards. Get the lead out of your fuels and maybe we can talk about getting it out of our children’s toys. First things first”. Photo: Peter Handley

Related Stories

Click on image

We know that our veteran airmen, had they known of the environmental damage they were doing with the fuel they were using, would have refused to take off on missions to lay waste to Nazi Germany or Imperial Japan. By standing down our operations and refusing to fly aircraft honouring them, we are in fact, in a strange manner, honouring them more. But we now seek to find a solution that will enable these enigmatic flying machines to continue to tell the stories of our brave, albeit polluting, war heroes. As with the great struggle that was the Second World War, technology has proven to be the answer.

Of course, there have been aircraft running on bio-fuels already. Right here in Ottawa, pilots of the National Research Council’s Flight Research Laboratory made the first 100% bio-fuelled flight more than two years ago. But sacrificing usable arable land to grow crops to make bio-fuel competes with food production. What if we could create a fuel which was primarily sourced from recycled seed-oils, enhanced by a much lower percentage of bio-fuels from a purpose-grown biomass? What if indeed!

Using the lower-compression 5-cylinder Kinner radial engine on our vintage Fleet Finch biplane trainer, we have made a technological breakthrough in recycled fuel technology that is a win-win situation for both the warbird community and the fast food industry. But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s talk about a new, and previously untapped source of bio-fuel—the casse-croûtes of Québec and the chip wagons of Ontario.

Liquid Gold, Timmins Tea, Bubbling Croûte

The casse-croûte is to Québec what the brasserie is to France, the chipper van to England, the cucina to Italy, or the rib shack to America. A weary and ravenous traveller or hungry mill worker in a small Québec village can take comfort in the Costco neon sign spelling out “Ouvert” from the counter window of a ramshackle structure, brightly painted former delivery van or re-purposed ancient camping trailer. This is the casse-croûte (or cabane à patate) the purveyor of “le hotdog steamé”, “le cheeseburger all-dress”, frites, pogos (corn dogs) and the culinary glory that is “Poutine” (roughly pronounced as poo-teen). A hungry man wheels his pickup truck, ATV or even snowmobile into a roadside casse-croûte and, for just a few “loonies” and “two-nies”, buys himself a steaming heap of golden, salted fries, soaked in peanut oil, crowned with half a pound of bland, squeaking, white cheddar cheese curds about the size of your toes, all smothered, like a chocolate sundae, in hot, thick beef gravy about the colour and consistency of used winter aviation oil.

Poutine... the bane of Canada’s national healthcare system. Wikipedia describes this national Canadian dish as a common Canadian dish, originally from Québec, made with potato fries, topped with a brown gravy-like sauce and cheese curds. This fast food dish can now be found across Canada, and is also found in some places in the northern United States, where it is sometimes required to be described due to its exotic nature. National and international chains like New York Fries, McDonald’s, A&W, KFC, Burger King, and Harvey’s also sell mass-market poutine in Canada (although not always country-wide).

The result of this seemingly strange and arterially sclerotic concoction is, quite frankly, culinary nirvana for people who feel no guilt in eating, altogether in one dish, the Top Six Worst Things You Can Eat—potatoes, oil, canned gravy, low-grade cheese tailings and salt. The result, my friends, is a mouth-watering dish of epic proportions, developed not in the haughty gourmet kitchens of Epicurean Europe or folksy Central America, but right here in the deep fryers of Eastern Ontario and casse-croûtes of old Québec. This is “Poutine”, a dish that seemed to creep out of Québec over the past fifty years, like a grease stain on your shirt, to become not just the beloved cultural guilt of French Canada, but rightly taking its place in the pantheon of Canada’s culinary gifts to the world—the Beavertail, Maple Sugar Pie, Back Bacon, Ketchup Chips, Tourtière, cod tongues, Kraft Dinner and Hawkins brand Cheezies.

For those of you who have never experienced the uber-guilty ecstasy of poutine, there are now gourmet poutine shops in New York, Paris, London and Dubai. If you have a bucket list (and you should have a bucket list) add “eat full, large size plate of poutine” at the bottom. You won’t regret it... Unless, of course, your arteries are already 95% blocked.

For all the deliciousness and joyous guilt that is the marvel known as poutine, there is a downside. For every pound of vegetable cooking oil that sluices through your veins or aids in evacuation, there are two pounds that, after transforming an acre of Prince Edward Island’s finest potatoes into poutine and other french fry dishes of cultural importance to Canadians, need to be dumped. This glutinous liquid, seamed with suspended potato and corn dog DNA, would traditionally be either drained into the buckets whence they came and land-filled, or worse, poured down the municipal waste water systems, there to join the flushable effluvium of a careless community—excreta, sanitary napkins, Grampa’s dentures, motor oil, and the odd stash of a weed-addled kid who thinks the Sûreté du Québec is at the door.

The Double Paradigm Shift

Some of the forward-thinkers at Vintage Wings of Canada saw an opportunity to shift two paradigms at once, to affect environmental change in two traditionally unconnected sectors at one time—the transportation industry and the fast food industry. We have the benefit of a number of Canada’s finest test pilots cum research scientists among our pilot cadre. Our scientests postulated that waste kitchen oils could be processed, filtered of detritus, and processed along with maize-based ethanol to produce a low grade fuel, suitable for heating and, if mixed with an additional 20% of kerosene, could be burned in lower compression automotive and even aircraft engines. The challenge was on.

The Canadian Association of Casse-croutiers (CACC) released a study in 2012 stating that over 3,400,000 litres of various vegetable-based oils (peanut, corn, canola, etc) were used in the making of fries for poutine alone. Of this considerable volume of oils soon to be dumped, some 2,835,000 litres were used right here in our home province of Québec and in Eastern Ontario.

CACC engineered for us the direct cooperation of more than 205 casse-croûtes and chip wagons within a two hundred kilometre radius of the Vintage Wings of Canada hangar where staff collected, during a period of two weeks, over 3,000 litres of high grade North Carolinian peanut oil laced with cooking detritus. Collection ranged from Peterborough, Ontario to Saint Hippolyte, Québec. The Executive Director of CACC, Gaétan “Crusty” Ryan, has been a key person in delivering the cooperation of casse-croûte operators in Western Québec and the chip wagon operators of Eastern Ontario. The CACC sponsored a specialized cooking oil recovery vehicle which travelled throughout the region for several weeks.

Volunteers at Vintage Wings, led by former fighter pilot Tim Timmins (an Irishman who knows a thing or two about potatoes), then mixed and filtered the golden oils, removing solid bits of fried potato, various meats and onion. Next, the resulting murky oil, known as “croustillinate” to Timmins and his oils distillation team, was endlessly hand strained and filtered through Hudson’s Bay 7-point blankets. The “clean” resultant liquid was then mixed with liquid Tractor Vaporizing Oil (TVO) and 20% pure ethanol from corn raised on Ottawa Valley farms. This new, more flammable, mixture was heated slowly to a rolling boil over three days using the maple sugaring vats at the Cabane à sucre Ange-Gardien, in the nearby community of Buckingham. The new, purer and clearer distillate was given the name of poutinol, smelling strongly of alcohol and fries, or as team members called the aroma—Midnight in Thurso. At this point, sadly, team leader Timmins was taken to hospital complaining of the “Sandy Hill Sweats” having tasted the distilled poutinol too many times.

The volunteers at Vintage Wings of Canada who put thousands of hours into the Future Fuels project assemble in front of the eco-friendly Fleet Finch on the ramp at Gatineau after the historic first flight. The pride and elation of the team is evident on their faces. This team of volunteers, not one professional chemical or petroleum engineer in the lot, have set the course for warbird and vintage aircraft operation for the next century. Left to right: Michael Virr (oil collection and distillation), Pierre Lapprand (fuel chemistry), John Longhair (oil collection and distillation, lubricants), Terry Cooper (fuel systems), George Mayer (fuel test manager), Graeme Goodlet (fuel chemistry), Luc Cloutier (engine test stand engineer) and Claude Brunette (Senior Project Manager-test). Missing is Team Lead Tim Timmins, still in rehab. Originally called the Future Fuels Team, after the success of the project the group of volunteers on the project have taken to calling themselves Team Poutene. After the Finch was rolled onto the ramp, Wallace the hangar dog had to be restrained from licking the fuselage aft of the exhaust stack. Photo: Evad Yellamo

After three days of distillation, the final “batch” amounted to less than 500 litres of pure poutinol. Additionally, there were more than 380 kilos of a brown sludge which were recycled into a new and quite tasty delicacy that the team called “cretons-suprêmes”—re-fried sludge balls, dipped in maple syrup—a fine reward for the Future Fuels Team after the weeks of hot, dirty and malodorous work.

Explosive and flammability tests conducted on a small batch of poutinol, blended with kerosene, gave spectacular results, with a low ignition temperature, and clean burn. The explosive results gave poutinol a quick nickname from the test team—“P-Stoff”, and the kerosene additive was called “K-Stoff”. The new Kerosene-Poutinol blended fuel was named “Poutene”. Combining the two fuels was a dangerous activity, completed outdoors away from any source of ignition. Over the following weeks, Team Poutene learned to handle the fuel safely—testing included everything from flinging a lit match into a bowl of poutene to serious and scientifically calibrated friction, flow and ignition tests.

Liquid gold. The Future Fuel Team took advantage of the fact that maple sugar operations are largely shut down during the coldest months of a Canadian winter, as the industry awaits the warmer late winter/early spring days when the sap flows in maple sugar bushes across eastern Canada and the United States. Using the vats of Cabane à sucre Ange-Gardien in nearby Buckingham, Québec, the team boiled the oil collected, filtering and straining over a period of three days. Seven batches of “croustillinate” were then blended with tractor vaporizing oil (TVO) and 20% corn-based ethanol from Ottawa Valley farms. The cooking oil/ethanol distillate was given the name “poutinol”. Photo via Team Future Fuel

After distillations, screening, filtering and skimming, each batch of poutinol distillate left behind about 20 kilograms of a golden brown sludge, made from particulate matter identified as part potato, part onion, part corndog, and part chicken fingers, all infused with a blend of vegetable oils. The team called these tailings “cretonite” and found a very creative use for the material. Photo via Team Future Fuel

The leftover cretonite was simmered in large pans over open fires, cooled, rolled into meatball-sized balls and dipped into maple syrup. This tasty delight, called creton-suprêmes by the team, are served warm and are, I assure you, an acquired taste. Photo: Team Future Fuels

The resultant distillate called “poutinol” had a relatively high flashpoint, making it unsuitable as an engine fuel at first. By mixing it further with 20% additional kerosene (TVO-tractor vaporising oil is also made from kerosene). This had the effect of greatly reducing the flashpoint and the viscosity. The nearly 500 litres of poutinol collected were blended with 100 litres of kerosene to create “poutene”. Three 200-litre drums of poutene were then stored outside the Vintage Wings hangar (for safety) through the month of February and most of March as samples were used to test the fuel’s performance on an engine test stand—a moped engine donated by the Moped Army. Each drum of poutene had to be warmed indoors for two days before it could be decanted and pumped by hand into the fuel tank of our Fleet Finch. Photo: Evad Yellamo

By early January of 2014, it was time to test the poutene fuel in an engine. A used and donated Moped engine was attached to a test stand on the Vintage Wings ramp and poutene was added to its tiny fuel tank. On the first kick of the starter, the little engine roared to life and then settled into that high-pitch scream that Mopeds are known for. Using a manual choke, various combinations of air and poutene fuel were played with. The fuel worked like a dream in all situations. A total of 25.25 running hours were racked up on the poutene-powered Moped engine. It was time to feed the new fuel to the Fleet Finch.

Parallel to the poutinol/poutene distillation process and testing done by the Future Fuels Team, our venerable Fleet Finch biplane training aircraft was being prepped for test flights using the new bio-fuel. These were mostly cosmetic, the most dramatic being the repainting of our future warbird turned “greenbird” in lime green, dubbed “envirocado”. The paint itself was 100% organic, distilled from the essences of avocado, aloe, turpentine plants and the feathers of migrating spring warblers. Despite angry reactions from local warbird paint experts and birders, Vintage Wings of Canada wanted our “French-fried Finch” to draw attention to itself on the air show circuit and in particular at Oshkosh’s AirVenture this summer. She was even given a new registration for her new role as a flying environmental spokesperson—C-FPFF for “Fries, Poutine and Fleet Finch”.

While the Future Fuels Team was working creating a new kind of fuel from discarded cooking oil, the mechanics at Vintech Aero disassembled the more-than-70-year-old biplane trainer and prepared it for repainting. Vintage Wings historian, Dave O’Malley was quick to point out that poutine was purported to have been invented in 1964 in the town of Drummondville, Québec, in the Eastern Townships by a man named Jean-Paul Roy. Drummondville is just 58 kilometres from Windsor Mills, Québec, where our Fleet Finch served with distinction during the Second World War at No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School. So, both poutine and the first poutene-powered aircraft are from the same small rural area of Québec! Photo: Evad Yellamo

The medium is the message and the message is that the world is transforming, much the same way that this venerable old Finch, which once taught our fathers and grandfathers to fly, will now teach a new generation of Canadians that the future holds great promise, provided we consume fast food at the same rate we do now. Sadly, you can’t please all the people all the time. Vintage Wings has received praise from both Transport Canada and Environment Canada, but a sharp rebuke from Health Canada! Health Canada has spoken out against the idea of connecting environmental stewardship with the consumption of fries, poutine and chip wagon fare. The CACC praised the initiative, issuing a statement just last week saying: “Vintage Wings of Canada’s new poutene fuel has provided a solution to two environmental issues at the same time. This new future fuel technology kills two birds with one stone, and both warbirds and poutine will continue to be enjoyed by Canadians far into the future”. Photo: Evad Yellamo

Even the oil circulating and lubricating the engine components is made from casse-croûte by-products. Some of the filtered poutinol was set aside before the adding of tractor vaporizing oil, ethanol and kerosene. This is used as a lubricating oil, but the Finch could not be left more than an hour outside in the winter with the engine off before the oil congealed and refused to flow. Photo: Evad Yellamo

There were many who decried the Fleet Finch’s new lime green paint scheme, stating that it made a mockery of the history of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Some just said it was ugly. Again, at Vintage Wings of Canada, the medium is the message, and the message is green. We admit that we had our head stuck in the sand over low lead high octane fuels in the past, but no more! We are bright green and proud of it!!! Photo: Evad Yellamo

A close-up of the Finch’s glass fuel gauge shows her tank is full of golden poutene prior to her first flight on 22 March 2014. Photo: Evad Yellamo

For the week leading up to the 22 March first flight, the ramp outside the Vintage Wings hangar was a busy and serious place... like a Canaveral launch pad while the fuel tanks are being filled on the old Space Shuttle. Each day, the Fleet Finch would be taken out, chocked and tied to a shipping container by the tail. Then one of the three drums of poutene would be wheeled out and hand-pumped to top up the Finch’s 32 gallon tank. Mechanic Paul Tremblay sat in the Finch and ran the engine at low and high revs for several hours a day. After each day’s run, the heads were removed from the cylinders and the pistons, rings, spark plugs and sleeves were inspected for wear, burning, and carbon build-up. Each day the result was the same—the engine was in perfect running order, with no visible problems whatsoever. It was time for a flight test.

22 March 2014 dawned a perfect flying day, one of the few bright blue days of an otherwise painfully cold and snowy winter in Eastern Canada—an auspicious beginning to the day’s flight. However, there were clouds on the western horizon, so the team made haste to top up the Vintage Wings of Canada Fleet Finch which, two years ago, was dedicated to fighter pilot and Transport Canada legend Hart Finley. As with all the engine runs of the past week, the Kinner snapped to life and banged away merrily. After warming the engine up, something that was time consuming in the sub-zero temperatures, the chocks were pulled and Arborpremo, wearing a heavy fur-lined parka, advanced the throttle. The little warbird turned greenbird began to move along the taxiway... powered by poutene. The Future Fuels Team walked and jogged alongside until the aircraft turned for the runway. The team climbed a snowbank and watched nervously as Arborpremo back-tracked the runway. He seemed to linger longer than usual at the far end of the runway which was about a kilometre from the waiting team members.

It seemed forever, but the Finch finally began its long roll down the runway. At the moment that the little green Finch lifted from the runway, one of the team cheered loudly, but then fell silent. The rest of the group waited until it was clear that the biplane was fully airborne, and then applauded tentatively. As the Finch climbed away to the west and the distant cloud bank, the air around the group wafted with the pleasant and now familiar whiff of fried potatoes and the group knew they were home free. Hugs, handshakes and high fives were exchanged all round, but the group stayed put until Arborpremo had made his planned five touch and goes. On the fifth landing, the greenbird came to a full stop before the taxiway turnoff, then moved on to the taxiway and trundled home—with the entire team wing walking Arborpemo all the way.

Test pilot George Arborpremo, wearing a hooded parka against the 80 mph winter gale that is an open cockpit in March, lifts off Runway 27 in the future-fueled Finch, the world’s first eco-friendly warbird. A pale plume of exhaust trails from her stack and folks on the ground were soon craving a big plate of poutine to celebrate. Of his historic flight, Arborpremo said: “That little Kinner radial ran like never before. While it didn’t have the get up and go it used to have, it ran more smoothly than I ever recall, and it smelled a hell of a lot better.” Photo: Evad Yellamo

That day, just two weeks ago, the eco-friendly warbird was born, cementing a bond between pilots and pilot food purveyors forevermore. This summer the French Fried Finch will be on a public relations tour, making appearances at the CACC’s Annual General Meeting in Cornwall and at no less than Oshkosh’s AirVenture 2014. An arrangement is already underway for the newly named “Team Poutene” to travel to Wisconsin to work with the Wisconsin maple syrup producers and diner operators to make a new batch of poutene locally. The arrival of the Vintage Wings Finch will mark the first international flight of an aircraft powered by recycled cooking oil. Shell Petroleum has invited the team to display the fuel process and the aircraft at Shell Square and has also expressed interest in the technology.

In a recent interview at Casse-croûte Chip Chip Hooray, Vintage Wings of Canada founder Mike Potter was exultant with the results, “For a long time, we’ve known of the environmental devastation wrought by warbirds, and we’ve decided to do something about it. No longer will we stand by and allow toxic emissions from our aircraft to jeopardize the future of our children. We once thought our mission was to honour our veterans’ service, to create leaders by sharing the lessons of duty, honour and sacrifice..., but we now see ourselves as leaders in green fuel technology, showing the way to the very peaceful, sustainable future our veterans fought for—with a truly homegrown solution.”

“The future is looking green, and it tastes delicious”, he said, as he forked a large clod of cheese curds and fries, dabbing the gravy from the corner of his mouth, “and I couldn’t be happier.”

We are proud to announce two new corporate sponsors who were introduced to us by the CACC – McCain Foods Canada, the largest producer of potatoes in the country and local cheese curd manufacturer St-Albert’s Cheese Co-operative/Fromagerie St-Albert, purveyors of the finest cheese curds in the province of Ontario. In celebration of the accomplishment and its future fuel demonstration program this summer, the aircraft received a custom registration C-FPFF for “Fries, Poutine and Fleet Finch”. It’s all about the marketing! Photo: Evad Yellamo