THE FAIREY-VINTECH FV.1 TURBOFISH

First Published April 1, 2019

This month, Vintage Wings of Canada put its Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber up for sale. The package deal includes a recent Vintech Aero-executed turbo-prop conversion that promises to provide the future owner with many years of trouble-free and low-cost operation.

In 1990, when Basler Turbo Conversions of Oshkosh Wisconsin rolled out the first Basler BT-67 with its DC-3 airframe and modern turbine engines, vintage aviation and radial engine enthusiasts around the world were aghast. Replacing the sonorous and oil-flinging Pratt and Whitney radials of the venerable Gooney Bird (or Dakota as we Canucks are fond of calling them) with pointy, keening and soulless turbo props (albeit Pratt and Whitney turbo props) was akin to mounting a Wankel in a Rolls-Royce, carbon fibre sails on the schooner Bluenose or a Maidenform bra on Venus de Milo. The Pratt and Whitneys were the emotional voice of the Golden Age of Airline Travel, the throaty sound of American success in aviation. People cringed at first and laughed the way one would giggle behind the back of an old matron with a botched facelift. But not for long

Soon, the realization that the then nearly 60-year-old Dakota was entering a second life as a viable, efficient and highly valued aviation asset, gave a new lens through which to view this beautiful old bird. The efficiencies and power of the new turbines combined with the capacity and eternal bone structure of the DC-3 increased the demand and value for the greatest aircraft ever designed and built in numbers. The value of a fresh-off-the-floor DC-3 or C-47 in the 1940s was around $80,000. Today, a fully tricked-out Basler remake will set an operator back $7,000,000 USD. And we are not talking here about a rare warbird meant to fly 40 hours a year. We are talking about a working aircraft meant to do that every week. The Basler turbo conversion went from laughing stock to sexy beast in very short order—as does any airplane that is a complete success.

Of course, the engineers and bean-counters at Basler knew that this would be the case. They had in mind the success of turbine conversions of two of the world’s finest radial-engined bush aircraft, the de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver and DHC-3 Otter. Each of these aircraft continue lengthy careers with no end in sight, both as radial-powered and turbine-powered aircraft. In fact, in the case of the Beaver, the turbine conversion came while the assembly line was still grinding out airframes, with 60 of the final airframes coming off the line as DHC-2 Mk. III Turbo Beavers. .

Basler BT-67s can now be found all over the world, from gunship variants in the Philippines to workhorses in the Far North such as this Kenn Borek Air example photographed at Yellowknife. Operating from the high arctic to Antarctica, the nine Basler BT-67s are the largest workhorses in the Kenn Borek fleet. Along with Kenn Borek and other commercial operations, are government operators such as the US Forestry Service, US Air Force, US Department of State and the Mauritanian, El Salvadoran, Guatemalan and Columbian Air Forces. The South African Air Force has a native-designed version of the BT-67. Earlier attempts at a turbine powered DC-3, such as Conroy Turbo Three and Tri-Motor Super Three had very limited success. Photo: Stephen Fochuk

During the 1960s, de Havilland Canada recognized the performance and maintenance benefits of a PT6 turboprop-powered Beaver. A total of 60 were constructed by de Havilland Canada at Downsview, Ontario and today Viking Air of Victoria, British Columbia continues to convert old radial Beavers to a new DHC-2 Mk. III Turbo Beaver standard. The success of this idea led Vintech Aero to study the possibility of upgrading the Swordfish in the same manner. Photo: Stephen Fochuk

The turboprop de Havilland reached its zenith with the beautiful DHC-3-T Turbo Otter. As in the case of the future TurboFish, turbine power detractors and radial-philes still admitted that it was a good-looking aircraft. Photo: Stephen Fochuk

Related Stories

Click on image

It was the successes in extending the lifespan of these world-class aircraft by replacing their radials with engines that run on easily-acquired jet fuels and provide unparalleled serviceability compared to piston-powered aircraft that led to Vintage Wings of Canada making a very bold and controversial decision to re-engineer and re-engine our historic Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber with a more economical Pratt and Whitney PT6 turbo prop. While we anticipated that this would infuriate warbird purists and unhinge Canadian heritage trolls who believe they own a part of all of the Michael Potter Collection aircraft, we needed to address our more than a decade-long problem with the Swordfish’s powerplant. That’s when the idea to re-engine with a more reliable turbine was first floated.

At first, the idea was sluffed off as nonsensical, anathema to our historically accurate sensibilities and sure to make us the laughing stock of the warbird world. But the more we thought about it, the more it began to take hold. Our program advisors from Forbes, Stynchman and Schoolie did buyer surveys a cost/benefit analysis of turbine conversion and the numbers were undeniable. Before we get into the details of the conversion however, a little background is in order.

Frustration is the Mother of Invention.

When Mike Potter and Vintage Wings of Canada first acquired its Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber from the Spence family in 2006, hopes were as high as the main mast on the German battleship Bismarck that soon we would be telling the story of the Royal Navy’s Canadian flying heroes of the Second World War. As one of only two operators of a vintage Swordfish worldwide, the Michael U. Potter Collection was now a serious player, considered one of the premier flying collections on the planet.

The Fairey Swordfish, slow and archaic even when operational, still went on to a historic career with the Royal Navy. Today, it remains one of the rarest Second World War warbirds in the world, with only two of the 2,400 built still in flying condition today. Photo: Royal Navy

When Swordfish HS 554, a former Royal Canadian Navy torpedo-bombing training aircraft, arrived at our hangar, the 100th Anniversary of Naval Aviation, as well as that of the Royal Canadian Navy, was looming four years hence. Our centenary plans included using it to tell the story of Canada’s naval aviation heroes of the Second World War, travelling the country along with our Royal Navy FG-1D Corsair. The two carrier-based flying legends were to be called The Grey Ghosts—A Cross-Canada Flying Tribute to 100 Years of the Canadian Navy. This name was chosen for its historic connections to Canadian naval aviators of the past. Firstly, the team’s Corsair was painted in the markings of and dedicated to the memory of Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray, Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve, the last Canadian to be awarded the Victoria Cross. The tragic story of the gallant action in which he was killed is told by historian Don McNeil in The Last Canadian VC. Secondly, and more directly, the name paid homage to The Grey Ghosts, the Royal Canadian Navy’s premier jet aerobatic team from VF-870 that flew McDonnell F2H Banshees from 1956–1960.

As a large open cockpit biplane, the “Fish” would also enable us to take two people up at a time to experience the sights, sounds and smells of the lumbering flight of one of the iconic aircraft that helped the Allies win the war. The potential for sponsored rides gave us hope that some of the costs of operation could be offset by enthusiasts and their sponsors seeking a flight in one of the rarest and most historic aircraft of the war. The aircraft, when purchased from the Spence family, was in excellent flying condition, but we felt the Bristol Pegasus engine could use a full makeover to get it ready for the planned coast-to-coast flying season in 2010. We didn’t want any maintenance issues and have her languishing far from her Vintage Wings of Canada home base. After assessing the condition of the motor, we decided to pull the Pegasus and send it to England for a simple overhaul. After all, the centennial was three years away. What could go wrong? A lot as it turned out.

When the “Fish” arrived from Southern Ontario on the fall of 2006, Vintage Wings of Canada staff and volunteers had great hopes that it would be one of the stars of the collection. Unfortunately, due to problems with parts acquisition and engine overhaulers and the quality of their work, she would only fly a total of 36 hours in eleven and a half years—and nearly all of that expended on a single trip to Oshkosh in 2011. Photo: Mike Henniger

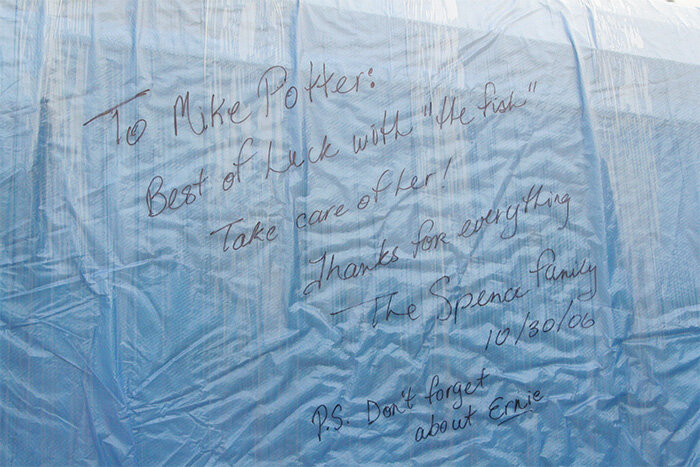

The wrapping of the Swordfish carried this note from her former owners and restorers, the Spence family from Southern Ontario. Despite the Spence family’s best wishes, Vintage Wings of Canada did not have good luck when it came to getting her airborne. The Post Script—Don’t forget about Ernie—references Ontario farmer Ernie Simmons of Tillsonburg, who had purchased a number of Swordfish airframes after the war and had stored them and a large number of North American Yales in the open for decades. After his death, his collection of rare Second World War airframes, including HS 554, was broken up and sold at auction. For more on this venerated man, his extraordinary collection and his tragic death, click here. Photo: Mike Henniger

The Grey Ghost Naval Centennial Flight crest for the Swordfish. With the upcoming centennial in our sights, we designed this crest and put it on the fuselage of our Swordfish. Sadly, while she wore the crest proudly for two years, she did not have an engine to go with it. While we waited anxiously for news about our overhaul, the Pegasus engine languished in England at a repair facility with other priorities. When the centennial came and went with the Swordfish collecting dust at the back of the hangar, we sadly stripped the crest from her sides. Design: Dave O’Malley

For much of her life with Vintage Wings of Canada, this has been the state of our Fairey Swordfish—beautiful, stout-hearted, flyable… but without a serviceable engine. Photo: Peter Handley

In the 1930s and 40s, the 690 hp Bristol Pegasus IIIM.3 radial was both reliable and ubiquitous. Today, a dearth of companies qualified to maintain and modify the nearly 85-year-old Pegasus design has meant that our Swordfish has languished at the back of our hangar without a working engine for 11 of the 12 years she has belonged to the Michael U. Potter Collection. Photo: Peter Handley

Despite constant pressure from the engineers at Vintech Aero (the maintenance organization behind Vintage Wings) to complete the overhaul work, the Pegasus entered an overhaul abyss from which she would not emerge for nearly five (yes, five) years; missing the centennial by a year and a half. During the centennial, the Robert Hampton Gray Corsair set out alone on a cross-Canada journey to celebrate Canada’s historical connection to naval aviation.

When the engine finally did arrive back from England, its exterior had been seriously damaged inside its container due to improper securing of the engine. Overall, the team was deeply unhappy with the delays and seriously dissatisfied with the quality of work done. Rather than risk a return to the “abyss” in England, Vintech Aero engineers made the repairs to the Pegasus in-house. After these were completed, the Pegasus was returned to the engine mounts on the Swordfish, and the massive three-bladed Fairey-Reed propeller was mounted. With the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture approaching in July, the team worked furiously to get ready for Oshkosh, hoping to make up for previous disappointments.

First flights were flown by veteran test pilot John Aitken and all seemed right with the power plant and the world. It was easy to forget the years of being held hostage by a paralyzed engine overhauler now that we had a working engine and a few test flights behind us.

On 25 July 2011 pilot Bob Childerhose, accompanied by a support aircraft, began the slow, thundering, oil-flinging journey to Oshkosh, Wisconsin via Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and then the western shore of Lake Michigan. The trip took eight hours over two days and was the equivalent of flying from Cardiff, Wales to Berlin, Germany or New York to Savannah, Georgia—not an adventure for the weak spirit. Despite some technical glitches en route, Nordo radio status and many hours of grueling travel, the Swordfish touched down at Whitman Airfield, streaming oil under her belly, to much fanfare and the rat-a-tat-tat of a thousand Nikon motor drives. Mission accomplished… sort of.

Bob Childerhose (left) cleans out spark plugs before takeoff at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario en route to Oshkosh. The Bristol Pegasus engine was “nine cylinders of ass-pain” say Vintech mechanics. From a mechanic’s perspective, the TurboFish is a dream machine. Gone are the testy Claudel-Hobson carburetor, the short lives of 18 sodium-filled Burt-McCollum exhaust valves, and of course, the complexities of the Farman epicyclic gearbox. Photo: Doug Fleck

At AirVenture, the Swordfish (the only example flying outside of England) was parked at centre stage and the oil wiped up. Members of the support team made presentations and took questions from the crowd each day. Spirits were high despite the engine and people were beginning to put the aggravation behind them. However, when it was time to leave, the Swordfish’s newly refurbished Bristol Pegasus engine had technical difficulties which kept her from flying home for a few days. Crews were swapped out and the engine issues cleared up. She made it home and flew several sponsored hops over the next two months, but by the end of the summer, the engine was still leaking oil and deemed unsafe for continued flying.

After copious amounts of money were consumed and nearly five years of waiting, the Pegasus had given up the ghost with a little over 30 hours on the clock! The mechanics at Vintech Aero shook their heads in utter disgust at the shoddy work and the shameful situation we now found ourselves. The work had been paid in full, the overhaul company was an ocean away and the last thing we wanted to do was ship it back there. We pulled the cylinders, moved her out of the way, draped the engine and began a search for a solution.

In the nearly seven intervening years since then we have made several overtures to North American overhaul specialists, but never got the kind of proposals, plans of action, cost structures or confidence that might have made us hand over the prized Bristol again. Instead, other restoration priorities and commitments to existing flying programs drew off the attention of management and engineers alike. The Swordfish languished at the back of the hangar and began an imperceptible slide from our consciousness. Until last summer.

As early as 2014, the idea of putting a turbo-prop engine on the Swordfish was floated—by no less than the Naval Attaché at the British High Commission, Commodore Sir Cyril Esmonde-Dingle. Over the next few years, Vintech Aero engineers toyed with the idea, finally getting a cost-benefit analysis done by aerospace program developers Forbes, Stynchman and Schoolie. The result showed that the installation of a Canadian-built Pratt and Whitney PT6 turbine would reduce operating costs, and would put the Swordfish in the air far sooner than rebuilding the Pegasus with its long list of unknowns—cylinders, sodium-filled valve stems, accessing leaded 100 Octane and more. This serviceability and greatly increased Time Between Overhaul (TBO) would make the Swordfish far more desirable if we decided to sell it. Most importantly, the PT6 would end more than a decade of the Swordfish sitting at the back of the hangar.

Though several of the AMEs at Vintech have experience maintaining jet and turbo prop engines in past stages of their careers, it was necessary to bring in a consultant with scads of recent turbine conversion experience—someone who had converted their radial-engined aircraft to PT6 power. The first name to come to mind was Flying Four-up Aerial Spraying in Nanton, Alberta. Over the past ten years, Flying Four-Up has been converting their fleet of 18 radial-powered AirTractor AT-300 crop dusters to the PT6-powered standard. The AirTractors were using the same PT6-A-67G turbine engine we were considering for the Swordfish. Like the Swordfish, the AirTractor is an over-designed, heavily-built aircraft designed to take rough treatment. The weak point for the crop dusters began to be the Pratt and Whitney Wasp radials that powered them—not the engine itself (a proven performer) but the parts, the expertise, the age and access to fuel. Going forward, their advice was to help us considerably.

The Flying Four-Up Chief of Maintenance Günther Sterchi, known as “Kowboy” to his colleagues, proved to be a font of critical knowledge when it came to preparing the Swordfish to accept a turbine. It was his recommendation, for instance, that the folding wings be welded permanently in the open position. Kowboy, whose father was Rommel’s barber and a POW in Alberta during the war, advised that the wing’s weakest points were the locking hinge points for the folding mechanism. These locks and hinges were not designed to handle the increased power and torque of the PT6. Using tubular Hy-Bor boron/carbon patch-plate stiffeners, chrome moly sleeve-plates and zip ties, the wings are now firmly and forever in the open position. The rest of the aircraft structure was deemed overbuilt for carrier landings and not in need of further strengthening. Sterchi visited Vintech Aero several times over the winter and conducted a series of seminars on PT6 conversion dos and don’ts, exhaust placement issues, fuel systems and ignition troubleshooting. Kowboy continued to monitor the conversion throughout the winter, and by late February, the TurboFish, as we were then calling it, was ready for engine tests.

Artist’s profile rendering of the Fairey Vintech TurboFish. While many decry the use of a modern turbo-prop engine, nearly everyone admits the aircraft looks pretty good. Computer modeling done by Forbes, Stynchman and Schoolie indicates that the Swordfish will have top-end speed increase of 77 knots due to streamlining and additional power. The native Bristol Pegasus produced 690 hp, but the new Pratt and Whitney Canada PT6A-67G turbine found on AirTractor and Ayres Trush agricultural aircraft outputs a healthy 1,294 equivalent shaft horsepower (eshp). Profile: Dave Merrill

Vintage Wings of Canada Chief Pilot John Aitken looks over the Swordfish’s new PT6 turbine at the conversion course given at Vintage Wings’ Gatineau facility by turbo-prop guru Günther “Kowboy” Sterchi of Nanton, Alberta’s Flying Four-Up Air Spray. Flying Four-Up is a world leader in radial to turbine conversions having converted more than a dozen of their Pratt and Whitney Wasp Junior radial-powered Air Tractor AT-300s to AT-400 standard with the switch to a PT6-A-67G turboprop. Photo: Günther Sterchi

As the project to mount the PT6 was coming to fruition, Vintech Aero employees conducted an impromptu naming contest for what would be essentially a new aircraft. The winning name, TurboFish, was selected because it blended advanced engine technology with the original name. There were several excellent runner-up names. My personal favourite and one that most people really wanted was the Fairey Windbag, a nod to Stringbag, the 70-year-old nickname for the Swordfish and a former volunteer at Vintage Wings. Some of the finalists were rather funny: JetFish, Turbot, OldFish, Northern Pike, Thunder Mullet (this one came with a slogan: Power up front, history in the back), FastAssBass, Tuna Rocket and the Holy Mackerel.

The TurboFish’s first test flight was on 7 March at the Gatinueau–Ottawa Executive Airport. Chief Pilot John Aitken, a veteran test-pilot had the duty and honour to fly the world’s first turbo-prop Swordfish on a sunny, clear and warm (for February in Gatineau) day. Given that he was sitting in an open cockpit behind a 1,294 Equivalent Shaft Horse Power PT6-A-67G turboprop in a -8 degrees Celsius and 160-knot slipstream, this was a blessing. The computer simulations run by Forbes, Stynchman and Schoolie predicted a 77-knot increase in top speed over its normal lumbering 124 knots at 5,000 ft. Aitken was warned not to test that limit (201 kts.) on the initial flights due to the age and brittleness of the fabric-covered flying surfaces. Both test flights were less than 30 minutes in duration and at an altitude of 2,000 feet.

An important development like the turbine-powered Swordfish needed not just a name, but a new logo. Keeping in character with the Disney-inspired mascots of the Second World War, we came up with a turbo-powered swordfish by the name of “Windy” after the TurboFish’s unofficial second name, “Windbag”. “Windy’s” image is now carried on the port side of the TurboFish.

With the switch to a turbine engine, we have done away with these smoky and polluting engine starts. Photo: Peter Handley

Gone will be the tedious hand-cranking of the massive inertia starter that requires the combined strength of two brawny Vintech engineers; replaced by a 28-volt electric wet-spline starter-generator with a maximum peak of 800 amps of current. Photo: Adam Smith

The TurboFish warms in the weak winter sun on the Vintage Wings of Canada ramp prior to the first of her two test flights on 7 March 2018. Gone were the back-breaking inertial starts, the dripping oil and the dirty spark plugs. Photo: Evad Yellamo

The old Bristol Pegasus-powered Swordfish was an extraordinary warbird experience for those lucky few who have had a ride in ours. The only other flying Swordfish in the world is operated by the Royal Navy in England and civilians are not able to experience its historic significance first hand. The TurboFish however will allow paying aviation and history enthusiasts to experience what it was like for Royal Navy Swordfish crews in the Bismarck action and the Battle of Taranto, minus the continuous spray of hot engine oil. The sound of the Pegasus engine will be added electronically via headsets along with recorded advertisements for sponsors. Photo: Adam Smith

In anticipation of vintage aviation enthusiasts decrying the loss of that clattering old Pegasus radial, the TurboFish will carry a single “Tannoy Torpedo”, a fibreglass replica of an 18-inch Mark XII air-launched “Redhead” torpedo mounted with two Bose speakers. This system allows spectators on the ground to get the full auditory experience. The Bose system has turbine noise reduction, cancelling the sound of the PT6 while emitting the more throaty and historically accurate “nine cylinders of ass-pain”. Passengers in the back will wear Bose headphones to hear the same sound as well as commercial announcements. For those who want a more historically correct experience, an aerosol dispenser in the aft cockpit will spray warm oil in their faces and on their clothes.

Vintage Wings of Canada chief pilot John Aitken test flew the TurboFish for the first time in early March of this year. Aitken, a veteran test pilot with the RCAF and the Flight Research Laboratory of the National Research Council, had flown HS 554 for the first time in 2011 after her Bristol Pegasus was reinstalled after “overhaul”. He is the only pilot in history who has flown both the radial-powered and the turbine-powered variants of the Swordfish. Commenting on the performance difference, Aitken said it was like “the Fish was holding on to its engine for dear life.” Photo: Peter Handley

Aitken’s job was to test and record the PT6’s power responses and Swordfish’s handling characteristics and control mechanisms. Having some experience flying with Bristol Pegasus power, Aitken said: “Before, the old Fish flew like she was a senior citizen—all wheeze, complaint and trepidation. But that TurboFish ran like a scalded dog. I felt I was sitting in a fuselage that was in hot pursuit of its engine. Those bracing wires sang like banshees on amphetamines.”

With the first successes of the flying program behind us, we are now certain that the Fairey Vintech FV.1 TurboFish will provide an unsurpassed Time Between Overhauls for Second World War warbirds. She will undoubtedly set a new benchmark for warbird operations in terms of serviceability and reliability—two qualities that are frankly missing in all high powered piston-engined combat aircraft of that era. If the concept proves the success we believe it will be, we now have plans to do away with the fussy and uber-expensive Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine on our Hawker Fury restoration, replacing it with a turbine too. Our studies show that a lightweight TP100 turbo prop engine from Czech manufacturer PBS Velká Bíteš would be the best fit.

While the PT6 conversion to the TurboFish has increased the sale price of the Swordfish by nearly $200,000.00, Vintech Aero is certain that the cost of operation will drop considerably over a ten-year period—more than offsetting the original cost of acquisition. The most important consideration is that the TurboFish program has put the Swordfish back in the sky where she truly belongs.

By Evad Yellamo