First Flights of Ottawa - Episode Three

By 1913, Ottawa was falling behind in the aviation world. It had been a full decade since the Wright Brothers’ first flight and still only one man had ever flown an aeroplane in the skies in Ottawa. That was Lee Hammond who had made demonstrations in Captain Thomas Scott Baldwin’s Red Devil at the Central Canada Exhibition a full two years before. Anyone who was smitten by aviation in Ottawa had to get their fix from local newspaper articles, the new selection of aviation magazines like France’s L’Aerophile, the UK’s Flight and the American Popular Science or by travelling to see a demonstration in another city or even village.

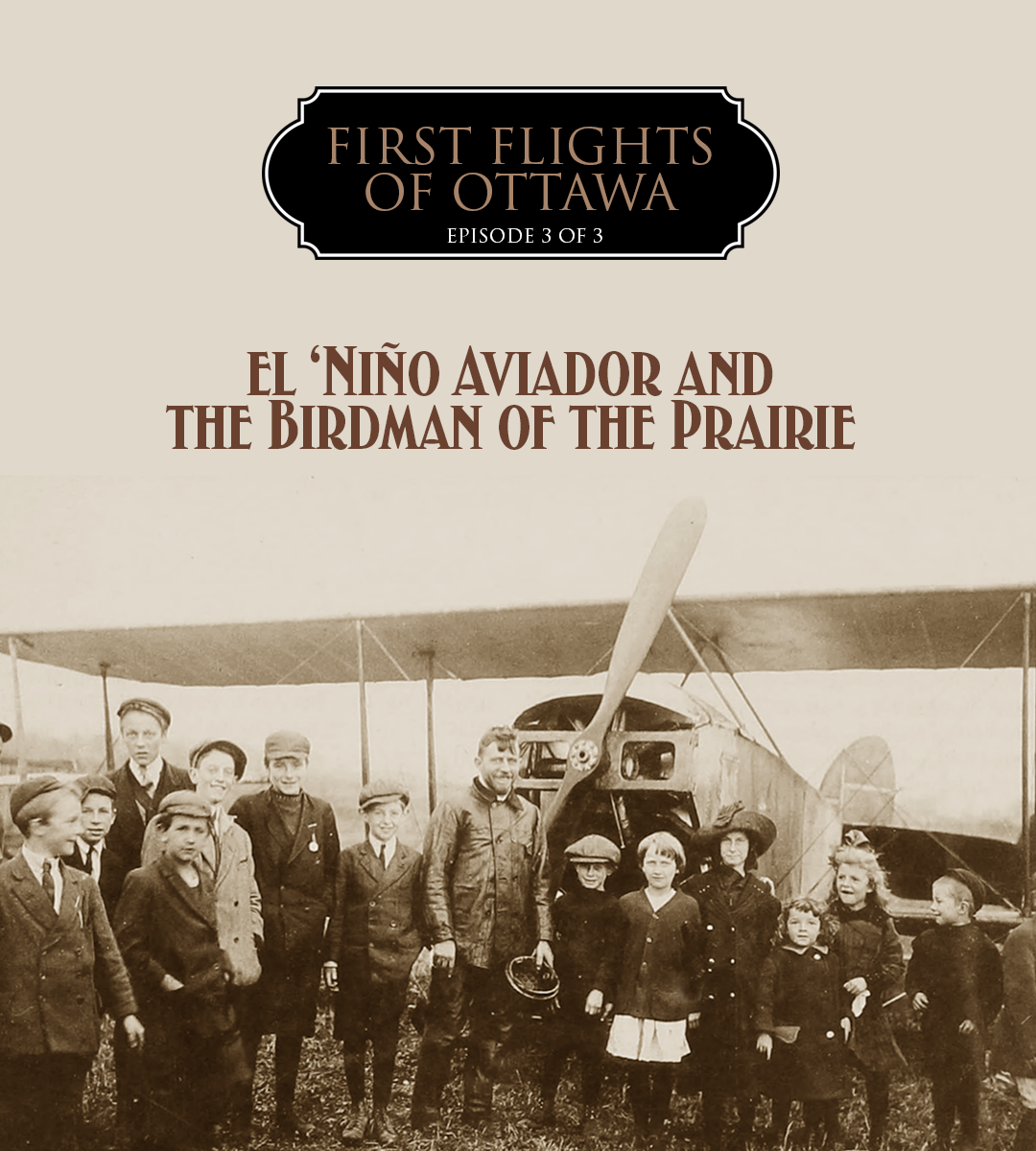

Any local aviation enthusiasts who followed the exploits of European and North American “aeronauts” would have been very familiar with the two men who were to finally break the flying drought in Ottawa in 1913. One was a boy-wonder who thrilled the citizens of Ottawa at the Exhibition and the other a man on a mission to be the first aviator to deliver the news and connect two Canadian provinces. The late summer and early fall of that year were busy times for the sheep meadow known as Slattery’s Field and at the agricultural fair grounds at Lansdowne Park. Here are their stories.

Peoli, the Boy Aviator, September 1913

Cecil Malcolm Peoli was still building flying models in 1911. He learned to fly at age 17 in 1912 and a year later he was flying a Baldwin Red Devil airplane around Parliament Hill in Ottawa. He started his own aircraft design and manufacturing company and designed an airplane by age 21 and was buried in the Bronx at the age of 22. His was a short but intensely lived life filled with considerable achievement and adoration. By the time his appearance at the Exhibition was announced, he was already a household name.

Cecil Peoli is arguably better known today not for his early pioneering flights or creating his own aircraft company but rather for design work he did before he was old enough to fly. As a member of the New York Model Aero Club, a boys club for aspiring aircraft designers and builders, he designed several award-winning airplanes in 1909. The plans for one of his designs, known today as the “Peoli Racer”, is still readily available for download across the internet.

Peoli gained the attention of Thomas Baldwin for these modelling successes and the Captain recruited him to train as an exhibition aviator. When Peoli was granted his certificate (No. 141) in June of 1912, he was the youngest licensed aviator in America. With not much more than a couple dozen hours under his belt, Baldwin took him on the road from their Long Island airfield at Mineola, New York to Barrie, Ontario for a week-long engagement and then on to Saint John, New Brunswick where the Boy Aviator made Maritime history.

Plans for Peoli’s twin propeller pusher “Peoli Racer” can be found on the internet today — one of the most enduring and popular designs in the history of the sport/hobby. According to The Second Boys' Book of Model Aeroplanes (1911), his rubber band-powered racer held the American record for time aloft at sixty-five seconds. He also claimed a distance record of 1,691 feet 6 inches. The book also stated that Peoli’s design “shows an intelligent appreciation of the principles involved”. Photos: The Second Boys' Book of Model Aeroplanes

Peoli’s youth was of great interest to the public. He was half the age Wilbur Wright was he when took his first flight and everywhere he went the local papers made much of his youth. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, in an article published while he was in Ottawa, described Peoli as:

“Of slight build, light-haired, and with a winning smile, Cecil seems even younger than he really is and while talking to this bashful, modest youth one can scarcely believe that he has been flying throughout the country for almost a year and that such veterans as Captain Baldwin, George Beatty and others consider him among the leading professional aviators in America.”

Despite the press’ focus on his youth, Cecil Peoli was as serious about flight and aerodynamics as were the Wrights and it was his dedication to aerodynamics, engineering and the stability of flight through building models that first drew the attention of Thomas Baldwin. No doubt Baldwin, who made his living through the demonstration of his Red Devil aircraft, also saw the crowd pleasing potential of having a boyish and good looking pilot for his demonstrations. Most likely Baldwin also understood that people would grow more confident with the new world of aviation if they saw that a mere “boy” could learn to fly with such confidence and skill.

A fine portrait of the “Boy Aviator” Cecil Peoli with a Baldwin Red Devil aircraft. During his tour of South America six months after Ottawa, he earned the sobriquet “el Niño Aviador” — The Boy Aviator. Note the transparency of the radiator.

Newspaper articles about Peoli’s flight all over Eastern Canada and the US invariably led with a paragraph about his age and appearance. And being a young male in his prime he loved to take women up for a flight. For instance, The Berlin News Record [the city changed its name from Berlin to Kitchener during the First World War] reported on 2 August, 1912.

“Peoli is the youngster whom Captain Baldwin brought out with a rapidity that is unparalleled in the annals of aviation. Within a few days after he first sat in an aeroplane he made big flights. He is considered one of the most skillful aviators who have ever appeared on Long Island. Before taking up his mother yesterday he made a flight with Miss Cassie McLaughlin. After swinging her around the field for ten minutes he took up Mrs. William Heina, the wife of another aviator. Then he invited Mrs. Peoli to take a seat in the craft.

The mother has absolutely no fear for her son. She showed her confidence by the contented way in which she took her seat in the biplane. She is a young woman. As the craft left the field she waved her hand to the spectators. As if to show he had no fear, young Peoli set his craft at a steep climbing angle and began to glide into the sky at once…

… “It was glorious,” said Mrs Peoli, as she stepped out of the machine and arranged her wind-tossed hair. “I never had any fear for Cecil when he first began to fly and now I am fascinated. I wish I were young enough to learn to fly. I would certainly become and aviatrice and keep my son company.”

Peoli’s mother Cassandra accompanied him to Ottawa and would witness him electrifying the crowds at the Exhibition Grounds and over the city. It shows just how young Peoli was when you see the youth of his mother. National Air and Space Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Although Cecil Peoli was soon to be the talk of the town in Ottawa, he had in fact flown in the region two months before — on July 4, 1913 in the tiny farming village of Lanark, Ontario, about 80 kilometres southwest of the capital. His flights in this rural village didn’t get the same sensational coverage in the Ottawa papers he would later receive, but the Citizen noted:

LANARK OLD BOYS HAVE SPLENDID DAY

Most Successful Aeroplane Flight, Governor General’s Foot Guards and Other Features

“Two brilliant and highly successful flights in an aeroplane by Paoli [sic]. the sensational American aviator, were features which added greatly to the prosperity of Friday, the banner day at the Old Boys Reunion at Lanark village. Great crowds of people literally swarmed into the village for the purpose of witnessing Paoli soar to the clouds in his Red Devil. The first ascension was scheduled to take place at two o’clock, but long before the hour Monahan farm, from which the flights were made, was thronged with people anxious for the appearance of the man who was going to fly great heights above them in his big machine.

When the airman did put in his appearance everybody gave him a welcome cheer. He was followed shortly afterwards by his machine, born on a large express van. This was the signal for another hearty cheer, in fact several cheers. At precisely two o’clock he stepped into his machine and in a few minutes was soaring through the air at a height of three thousand six hundred feet. While up in the air he gave several thrilling demonstrations of how an airship can be guided up and down and in every direction. The great crowd below emphasized their pleasure and appreciation by cheer after cheer and rounds of hand-clapping.”

It’s hard to believe that the young man who had been setting the aviation world on fire flying from a farmer’s field 80 kilometres from Ottawa got such a paucity of coverage, especially when one thinks of the dearth of flying activity in the city. The Ottawa Journal merely reported in a short piece on the Lanark celebrations that:

“The parade wound up at the ball grounds, where meals were served at 1:30 o’clock, after which the aeroplane flight by Paoli [sic] will be of intense interest. The aeroplane is owned by Captain Thomas Baldwin of New York.”

That’s all they wrote. Despite what seemed like disinterest on the part of the local press, two months later, he was finally celebrated when he returned to make demonstration flights for the grand stand crowd at the Central Canada Exhibition. On Saturday, September 6th, Peoli, his youthful mother and their entourage were back and the Ottawa Citizen reported that:

“The aeroplane, which is to make the first flight at 11 a.m. Monday, is now safely installed in a big tent at the east end of the grand stand. Cecil Peoli, the aviator, is taking every precaution against mishaps. Some wires had to be removed to make room for the tent and every wire that might interfere with the machine before the grand stand has been taken away, portable poles being used for lighting purposes instead. An open area 200 by 800 feet is required for the safe ascent and descent of the machine. Manager Thomas Baldwin of New York is on the way to Ottawa to further inspect the surroundings.”

Despite his age, Peoli was a cautious aviator. On opening day he did not respond to pressures when high winds made flying far too dangerous for the fragile airplane with the light wing loading, instead he waited until the next day for conditions to improve. The Ottawa Citizen of September 8, explained Peoli’s predicament ending as always on a note about his charms :

Even before eight o’clock [AM] there was a big crowd of kiddies waiting at the main gates. They met with one disappointment, however, through the announcement that Cecil M. Peoli, the young aeronaut, would be unable to make an ascent in his aeroplane because of the high wind from the northwest, which was whisking over the grand stand at 11:30, the time he was due to fly, at a rate of 20 miles an hour. If the wind drops or veers round in another direction he will fly this afternoon at 4 o’clock.

PEOLI DISAPPOINTED

Peoli said that if he had attempted to fly this morning the wind would have keeled his machine over and something disastrous would have happened. He was keenly disappointed over not being able to make a flight. It is only the second time this year when he has failed to fly on scheduled time.

Peoli is only 18 years old [sic], and a smart, very handsome man. He is the youngest aeronaut in the world. His machine is stored in a big tent near the end of the grand stand. Weather permitting he will make two flights daily while the “Ex” is on, the first at 11:30 in the morning and the other at 4 o’clock in the afternoon.”

When Cecil Peoli flew from Lansdowne Park in 1913 and then circled the Parliament Buildings three times, he was just 19 years old. Though young, he demonstrated the Baldwin Red Devil aircraft from Kitchener to Caracas, from Saint John, New Brunswick to Indiana. Photo: National Air and Space Museum Archives, Harold E. Morehouse Flying Pioneers Biographies Collection

On the 9th, the continuing issue with high winds had forced Peoli to move his operation to Slattery’s Field where there was more room to take off and land compared to the limited and defined area in front of the grand stand. It is not known if he flew there or if his aircraft was dismantled and moved by wagon or truck. The Ottawa Citizen reported:

At ten o’clock the plucky young aviator, Cecil Peoli, announced to secretary McMahon that conditions were favourable for a flight and was told to go ahead and make it. But within fifteen minutes a strong wind sprang up. … … directors had a conference this morning and decided that the aviator should be permitted to transfer his aeroplane to Slattery’s field to start. This is the field from where the flights were made two years ago. Peoli says he will make a flight this afternoon from the Slattery field, passing right in front of the grand stand, and that he will probably alight in front of the stand. As soon as the wind goes down the aeroplane will be brought back and the ascensions will be made from in front of the stands.”

Finally, after delays and the transfer of the Red Devil to Slattery’s Field Peoli was finally in the air as the Ottawa Citizen reported:

“The two flights of the aeroplane were without doubt the best ever seen in Ottawa. Particularly was this the case in the last flight about 3 o’clock when the birdman reached an altitude of almost 5,000 feet, only lacking 300 feet of being a mile above ground. It’s a long way from mother earth. The flights started in Slattery’s field, that field which the exhibition usually makes famous once a year. It lies across the canal from the fair grounds. On leaving the field on the second flight he soared slowly over the grounds and spiralled higher and higher until the airship was scarcely more than a speck in the heavens. He seemed to have the biplane under perfect control and circled around so that he could best be seen by the crowds on the grandstand.

Then he started the descent. Slowly he came down like a great bird looking for a place to light and floated over Bank Street a few feet above the wires he carefully sailed over the electric wires at the west end of the grounds before the grandstand. The planes turned down and with a deliberation that was marvelous, the ship skimmed a few feet above the ground until almost directly in front of the center of the stand. It lightly touched the ground, ran about 100 feet, along the field east of the ball diamond and stopped. The crowds cheered again and again at the beautiful landing. …

… Mr. Peoli is only 19 years old and is one of the youngest aviators in the business. He hopes to be able to start from before the grandstand sometime during the week. “It’s such a small space to start from that unless the wind is just right, it would be impossible. I will try it if the wind is blowing up or down the track parallel with the grandstand. It all depends on the wind whether I can start from the grounds. There is not much room there even to light.”

The aviator’s mother watched the flight and took a keen interest in getting the machine again under the tent beside the tracks. It is a piece of work that needs considerable care and everyone on the grounds wanted to help.”

The area marked in yellow is recognized by Ottawa East researchers as the sheep and cattle meadow come airfield known as Slattery’s Field. Images via http://history.ottawaeast.ca/

While these flights delighted the crowd, it was his flights on Thursday, September 11, that truly electrified the citizens of Ottawa as thy cheered from Lansdowne Park or craned their necks to see him flying overhead in downtown Ottawa and circling the Parliament Buildings two miles from the Exhibition grounds. The Ottawa Citizen describes his feat of airmanship:

SPLENDID FLIGHT OF AEROPLANE OVER CITY

Peoli Viewed by Many Thousands in Graceful Work Today

“Hundreds of admiring spectators saw Cecil Peoli with his aeroplane make a wide detour of the city today. He started from the front of the grandstand and flew in a curve towards Hintonburg, then changed his direction and took a line over Bank street to the parliament buildings. He flew at a great height and was seen by thousands soaring majestically away from the smoke. Nearing parliament hill he veered to the eastward, passed directly over the Citizen building [which used to be at the corner of O’Connor and Queen Streets - ed] and when about over the Chateau Laurier was seen to dip his planes and descend at a terrific speed that sent a thrill through the many gazers on the roofs of the higher buildings of the city.

As gracefully as a gull he checked his speed and circled thrice around the towers of the government buildings. With glasses those on top of the Citizen building could see the face of the aviator as he carefully handled the steering wheel and levers. He seemed to be thoroughly enjoying himself. After completing [his] big triple circle he rose again and took a course over the west of Bank street to the fair grounds. Before reaching the grandstand he crossed over Bank street and curving around alighted in front of the stand from the east end.”

Though this is a composite image of the Parliament Buildings as they were and an image of Peoli flying the Red Devil, it gives one a feel of what it would have looked like for a guest at the Chateau Laurier looking out from his window in 1913 to see the Boy Aviator circle Parliament Hill three times.

A “headless” Baldwin Red Devil biplane similar to the one Cecil Peoli flew over Ottawa in September of 1913. It differs from the Red Devil flown by Lee Hammond two years earlier in that the pitch controlling horizontal stabilizer is at the rear of the fuselage as most aircraft are configured today. Hammond’s earlier Red Devil had a large pitch control surface ahead of the pilot seat. Photo: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The Ottawa Journal, less effusive as always stated:

FLIES ALL OVER CITY IN AIRSHIP

First Flight Over Capital Made Today

Remarkable Demonstration by Peoli

Made Fast Trip From Lansdowne Park: Circled Over Sparks Street and Parliament Buildings and Returned to Exhibition Grounds

Considerable excitement prevailed in the city about noon today when the aeroplane from the Exhibition Grounds was seen soaring through the air over the Parliament Buildings. The machine was at such a height as to allow a good view and the form of Peoli, the airman, was easily discernible. The roar of the propeller attracted all attention as the machine circled the city.

It was originally intended to alight on the grounds in front of Parliament Buildings, but for some reason or other the plan did not materialize, and a disappointed crowd watched the airman slide toward the fair grounds. [surrounded by buildings and towers on four sides, the lawn in front of the Centre Block was no place to attempt a landing-Ed]

It was a hard act to follow, and Peoli kept his remaining demonstrations close to Lansdowne for the remainder of his stay. He did change up his show on Friday as the Ottawa Citizen of September 13 stated:

The plucky young aviator pulled off a new stunt when he soared down in front of the grand stand passing in a line lower than the roof of the stand and waving at the people as he passed. Then he planed up again, circled around and made a great landing directly opposite the middle of the stand.

The youth of Cecil Peoli, “the darling of the airways”, can be seen in this photo of him with the fatherly Captain Tom Baldwin (arms folded) taken just three weeks after his appearances in Ottawa. Photo: the Bain collection at the Library of Congress

Peoli made his last flight in Ottawa on Sunday, September 14th, flying from Slattery’s Field in what the Ottawa Citizen called the only “redeeming feature” of the lacklustre closing day of the yearly exhibition. He left Ottawa having made some local history and thrilling the good citizens. He continued to demonstrate Red Devil aircraft for Baldwin for two more years, but in January 1915, he formed the Peoli Aeroplane Company with a group of investors and bid successfully on a U.S. Navy contract to supply nine hydro-aeroplanes. The company planned to produce an armour-plated plane for New York and St. Louis cross-country trials. The young Peoli was now on the cusp of a successful career as an aircraft designer and manufacturer which promised to bring him even more respect and wealth.

Peoli's design for the contract was as a sesquiplane with a 150 hp Rausenberger motor, a 48-foot wing span on the upper surface and 32 foot spread on the lower plane. It was manufactured for Peoli and his backers by the Washington Aeroplane Company, which they had purchased. During its first test flight at the U.S. Army Aviation Field in College Park, Maryland on April 12, 1915, the aircraft collapsed in flight and crashed at the edge of the airfield after failing to rise higher than 100 feet. Young and promising Cecil Peoli was killed instantly.

Two years after his Ottawa flights, at the age of 21, he was killed instantly in a crash of an aircraft of his own design (above) at College Park Airport north of Washington D.C.. The company he created with the backing of some prominent New York business men was shortly dissolved.

A Flying Publicity Stunt, October, 1913

A month later, the citizens and political denizens of the capital would see yet another aviator in the skies over the city and at Slattery’s Field, now the unofficial Ottawa airport. But this would be a different kind of demonstration. Instead of entertaining the slack-jawed locals and showing them a flying machine for the first time, an aeroplane would come to town with a job to do. Of sorts.

Up to this point, the Red Devil aeroplanes that had flown in Ottawa in 1911 and 1913 were simply showpieces and their pilots — Hammond and Peoli — were putting them through their paces to show paying customers just what they were capable of. At the most, they occasionally took a passenger up for a thrill of a lifetime. Since 1903 and the Wright’s first flight, the demonstration of flight was the number one job of aeroplanes and their “bird men”. Many of these bird men or aeronauts as they were also called could see the steady progression of technological development. Aeroplanes, though lightyears from the reliability of today, were becoming more so with every new design. In particular, aero engine technology was developing apace. Pilots were taking longer and longer flights, connecting cities, and opening routes. Monetary prizes from wealthy businessmen and newspapers looking for more readership fuelled development.

Men like Thomas Baldwin, Lee Hammond, and George Mestache had thrilled audiences in cities and even villages across the country, but when they had satisfied their contracts they struck their tents, disassembled and crated their “aerodromes” and moved on to the next city by train. Here they were showing everyone a new way to travel, yet the reliability and range of their machines meant they had to go “bi-modal”. In 1911, J. A. D. McCurdy, Canada’s first pilot, had made the world’s first oceanic flight (from Florida to Cuba) and Canada’s first intercity flight (Hamilton to Toronto) yet, no two provinces in Canada had been connected by air by 1913. That was about to change.

In 1913, newspapers were the only way people got their news — community national or international. Every city had numerous broadsheet papers published every day of the week except Sunday and every small town and village published their own smaller papers. With the advent of TV and the internet, those days have long gone but back in 1913, there was always room for another broadsheet in a city as big as Montreal. It was into that crowded news environment that investors and editors were about to launch a new broadsheet daily called the Montreal Daily Mail, an paper with royalist leanings and a desire to maintain strong cultural ties to the United Kingdom. Their desire was to become a national newspaper like Toronto’s Evening Star or Globe.

With all the newspapers in Montreal, both French and English, it would be difficult to get noticed, so the management imagined a publicity stunt that would garner attention and get the Daily Mail noticed by Canada’s political elite, presently ensconced in Ottawa 100 miles to the west. The plan required an aeroplane and pilot to pick up copies of the first issue of the paper, hot off the press, and fly them to Ottawa where they would be delivered to former Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier, Prime Minister Robert Borden, Chief Justice Charles Fitzpatrick and the mayor of Ottawa, the Hon. James A. Ellis, MPP. The assumption of the marketing team was that other newspapers would cover the story and the news would travel accordingly. They didn’t count on the reluctance of Montreal’s newspapers to report on a positive story about their competitors. In an article published in the Montreal Gazette 104 years later in 2017, the paper owned up to shunning the publicity stunt and anything to do with the Daily Mail [except probably its failure four years later - Ed]:

“It was trumpeted as the first cross-country flight in Canada, and the first to carry a commercial cargo in this country. But not a word on this landmark feat appeared in The Gazette, either that day or the next. The reason? The flight was a stunt sponsored by a brand new Montreal newspaper, the Daily Mail, to mark its debut, and The Gazette had no wish to give publicity to the upstart – no matter how big a story it meant ignoring.”

To courier the newspapers by air, they hired an experienced aviator from Grinnell, Iowa by the name of William C. “Billy” Robinson who would make the flight in his Lillie-Vought tractor biplane, following the Ottawa River and “iron compass” [rail line] from the suburbs of Montreal to those of Ottawa. Then they took out half-page advertisements in the Ottawa Journal and Citizen to get Ottawans excited about the arrival of the new paper by air. The flight was scheduled for October 8th, 1913, the same day that the Daily Mail presses would roll for the very first time.

The Montreal Daily ran half-page ads in both Ottawa’s broadsheet dailies — the Journal and the Citizen. While the papers accepted the Daily Mail’s advertising spend, they were less inclined to celebrate their competitor’s success. Image via Newspapers.com

Iowan William Cornelius “Billy” Robinson, “Bird Man of the Prairie”, was one of a number of larger-than-life aviation pioneers, now forgotten, who travelled North America as quasi-circus performers demonstrating manned flight to enthusiastic spectators from Ottawa, Ontario to Ottawa, Kansas. Right: Always the promoter of aviation’s utility — in the Dec. 28, 1915 issue of the Grinnell Herald, we see Billy Robinson delivering a 2 lb. sample of Sam Nelson Jr. Company’s Amber Rice popcorn to Eugene Handy, the “Popcorn King” of Iowa City. Robinson flew the 65-mile distance in 46 minutes. Fedex was still 45 years in the future.

They chose a field near the farming community of Snowdon Junction west of Montreal as the place where the flight would begin. According to a newspaper account, Robinson had scouted his departure field at Snowdon Junction, taken the train to Ottawa to reconnoiter his landing ground and then concluded that he could make the trip in 90 minutes without stopping en route. In the end, he would take twice that flying time and have to land five times en route. The original plan required Robinson to take off and instead of heading directly to Ottawa turn toward Montreal to make a show of the departure. He was to circle Fletcher’s Field (now called Jeanne Mance Park) at the eastern base of Mount Royal before turning west and picking up the rail line to Ottawa.

Unfortunately, when Robinson arrived at the field near Snowdon Junction, he discovered that his aeroplane had been seriously damaged in rail transit from Chicago. His mechanics were working on it, but the delays caused him to cancel plans to fly over Montreal and Fletcher’s Field. He was quoted as saying, “Tell the people who may be waiting for me at Fletchers Field that I apologize for not appearing there this morning, but you may announce that I will return from Ottawa and give them an exhibition that will repay them for waiting.”

William C. Robinson in the Lillie-Vought biplane (also sometimes referred to as a Lillie Tractor) which he used for his historic flight from Montreal to Ottawa to deliver a bundle of Montreal Daily Mail newspapers to the nation’s capital. He made the 116-mile flight in two hours and 55 minutes, establishing the first long-distance flight in Canada. This crude aircraft was the first airplane design by Chance Milton Vought, whose namesake company would eventually design the Corsair fighter of the Second World War and the magnificent F-8 Crusader jet fighter. This particular biplane does not have the covered fuselage of the example that Robinson brought to Ottawa, so may be another and the MAGNIFICENT Photo via avialogs.com

Robinson’s Lillie-Vought aircraft at Snowdon Junction on October 8, 1913 with Mayor Lavallée of Montreal (second from right) and executives from The Montreal Daily Mail waiting for Robinson to depart. Photo via Grinnell Public Archives

According to the Grinnell Public Library Archives, this photo depicts Robinson at Montreal with school children and the Lillie-Vought biplane he flew from Montreal to Ottawa. It’s possible that some of these kids are the children of the Daily Mail executives and other dignitaries there that day as they are well dressed and quite different from the local farm kids. Here we get a good look at the 50 hp French Gnome engine that powered the aircraft. According to the Harold E, Moorehouse Flying Pioneers Biographies Collection at the Smithsonian Institution, Robinson “started flying [October 1] the Lillie tractor with a 50 h.p. Gnome engine at Cicero [Chicago], then took it to Canada for some exhibition and cross-country flights there.” Photo via University of Iowa

In Montreal, the mist has cleared and Robinson is stowing newspapers from B. A. McNabb the editor of the Montreal Daily Mail. Though The Daily Mail made an attempt to get noticed with its flying publicity stunt, the newspaper would be defunct in lest than four years. Photo: PA-165980, National Archives of Canada

At Snowdon Junction, he was met by the representatives of The Daily Mail as well as an entourage accompanying Montreal Mayor Louis-Arsène Lavallée. There were speeches and photo-ops with dignitaries and their children before Robinson was handed several rolled copies of the first run of the first issue of the new broadsheet, which he would stow in the cockpit with him.

His Worship Mayor Lavallée had arrived at 8:15 in the morning, having been “whirled out to Snowdon Junction by automobile”. Though he would have to wait a couple of hours for the flight to commence, he was excited about seeing an aeroplane for the first time and seemed to be more enthusiastic than anyone present, giving a cheerleading speech prior to Robinson starting his engine:

“I cannot let this occasion pass without making a few remarks. Most of you are journalists here, and you know the difficulties in making impromptu speeches, but let me tell you that the city of Montreal will hear of this aeroplane flight with great pleasure. This event marks a new era in the development and prosperity of our good city. A newspaper— and especially a new one— is not an ordinary enterprise. It can do a great deal for the good and prosperity of a country and of a city like Montreal, and it can also do a lot of harm. But judging from what I know of those at the head of this new paper, I believe that the best results will follow the undertaking.”

After praising the Daily Mail effusively for their British leanings, he turned to Robinson saying rather ominously:

“I wish you to deliver to the Administrator of this country, to the Prime Minister of Canada and to Sir Wilfred Laurier, the chief of the Opposition, these papers. I hope your life will be spared, because the work you are doing is the work of a hero.”

Montreal Mayor Louis-Arsène Lavallée offers up some words of political wisdom at Snowdon Junction as he bids Robinson a safe flight. At first I thought his homburg was blowing away in the wind, but other photos from the same time show that it was resting on the wing and a wire. Photo via Grinnell Public Archives

Robinson replied “I’ll do my best.” and then, having had enough of the mayor’s speechifying, immediately started the motor. According to the paper, a dozen willing men rushed forward to help push the aircraft and were promptly enveloped in a cloud of dust. He took off north and turned to fly back across the field where the dignitaries, children and others waved their handkerchiefs in appreciation and good luck. Then he turned due west, intending to cross the Lake of Two Mountains (Lac des deux montagnes, as it is known today) and then follow the south shore of the Ottawa River.

Robinson on take-off at Snowdon Junction. Final destination: Ottawa — Montreal Daily Mail Photo via Grinnell Public Archives

He didn’t get too far. Fifteen minutes after take off, a fuel line problem forced him down in Lachine where he spent two hours to repair the problem. One of his mechanics had been following his flight in an automobile for the first few miles and was on the scene quickly. Once in the air again he was forced down 20 minutes later at Ste Anne de Bellevue to repair a detached spark plug wire. Here he acquired a couple of sandwiches from a French woman that were “very nice”.

Robinson, engine gunning, exhaust smoking, is set to take off from Lachine, Quebec after fixing his broken fuel line. Photo via Drake University Digital Collection

Robinson lifting off on his way to Ottawa, likely at Lachine. Photo via Grinnell Public Archives

Finally getting the recalcitrant ship humming, he took off following the CPR rail line along the Ottawa River for 25 minutes to the hamlet of Choisy, Quebec west of the English enclave of Hudson where assistants had placed a huge white canvas cross in a farmer’s field to mark the spot where fuel had been cached and an assistant was waiting. Robinson, who had used up a large quantity of fuel in his unplanned stops at Lachine and Ste. Anne’s, stated he had only a quart of gasoline left when he landed for fuel. He refuelled quickly and was off for Caledonia Springs, Ontario, between the towns of VanKleek Hill and Alfred, where another fuel cache was positioned. While he waited for fuel to be poured into his tank from jerry cans, he walked over to the massive white CPR hotel at Caledonia Springs to sample a glass of their famed mineral water.

Caledonia Springs, “The Old Canadian Sanitarium and Summer Resort” boasted a grand white and ginger-breaded CPR hotel with a three story wrap-around porch where visitors could relax in the shade while they took the waters that the spa was known for. One can imagine a castor oil stained Robinson in oilskins sitting on a rattan chair in the main portico while he downed a tall glass of their famed mineral waters. Photo: Library and Archives Canada

After gassing up in Caledonia Springs, he took off following the rail line to Leonard Station (near Navan, Ontario) where he took on fuel for the last time. The description of the reaction of the locals in the Montreal Daily Mail is worth a read:

One of the most exciting events that every occurred in the history of Leonard Station, Ont., took place at 4:30 o’clock yesterday afternoon when Aviator Robinson made his fourth [sic] and last descent on the way to Ottawa. …

…. His face grimy with oil, Aviator Robinson stepped out of the aeroplane, surrounded by a silent, wondering group of men who were experts on agriculture, but had never before seen as ship of the air. George Conway, the man with the gasoline, rushed to the scene, helped the grimy aviator to fill the tank once more, and twenty minutes later, the propellers began to whirl once more and the aeroplane disappeared in the direction of Ottawa, leaving the good people of Leonard with much weighty matter for reflection.”

The front page of Volume 1, No. 2 of The Montreal Daily Mail touts the historic flight from the day before. Image via Avialogs.com

Page 2 of the October 9th issue of The Montreal Daily Mail featured a map of the Robinson’s route with Montreal Mayor Lavallée at right and Ottawa mayor Ellis at left. It is clear that this map was created well before the actual flight as it depicts a Bleriot monoplane when in actuality, Robinson flew a Lillie-Vought biplane. Below are photos of the recipients of the air-shipped newspapers — Former Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier, Prime Minister Robert Borden and Chief Justice Charles Fitzpatrick.

A photo from Library and Archives Canada claimed to be taken during Robinson’s flight from Montreal to Ottawa — likely at the fuel stop at Caledonia Springs, in a farmer’s field between Vankleek Hill and Plantagenet, Ontario. Curious as to what the light is reflecting from in this photo — perhaps a hinged panel tilted up from the engine cowling to inspect oil level. Photo via oldottawasouth.ca, Peter Pigott and Library & Archives Canada/PA-165978

A poor image from The Montreal Daily Mail, October 11, 1913 shows a group of boys and farmers inspecting the flying machine while Robinson is refuelled at Caledonia Springs. One can only imagine the excitement. Photo: Montreal Daily Mail

From the moment he took off at Leonard Station and climbed high in the air, the cloud and mists that had hounded him all the way that day cleared:

”For the last eighteen miles from Leonard, I could see the country pretty well, the mist having cleared away a good deal. The first knowledge I had of the capital was when I recognized the big bend in the river and the large Parliament buildings. They showed up well. By the way, there is a good deal more of the area of this part of the country covered by water than my map shows. Then I discerned the Chateau Laurier and the mass of houses and other buildings in the city. The exhibition grounds [Lansdowne Park] I located first by the half-mile [race] track. That is a thing that always shows up fine. The tracks look light colored because they reflect the light as against the dark green of the grass and the darker green of the trees. I came over towards the exhibition grounds, but I saw the people all over the field, and I also thought it not very safe to land from the east as I would have to do because of the west wind, so I wheeled around and went back to the field across the canal.

His late arrival seems to have conflicted with a practice for the Ottawa Rough Riders football team. In addition he felt the winds were not conducive to a landing there, so he turned back east and set up to land at Slattery’s Field, which no doubt he had heard about in his recce trip to Ottawa.

There, just in landing I had one of the most exciting experiences of the whole trip. There was a horse in the field, but I reckoned on running along the other side and avoiding it. As I came down, however, the animal ran in front of me, and I had to raise one wing and make a very sharp turn to miss striking it. In the other fields there were cattle but I had now trouble with them.”

A photo of the Lillie-Viought biplane, possibly taken at Slattery’s Field, Ottawa.

While the Ottawa Journal took the Montreal Daily’s advertising dollars then buried a short story in the newspaper on the 9th, The Ottawa Citizen ran a longer story about the flight [which had not yet been completed at time of printing] on the front page of October 8’s evening edition:

MONTREAL-OTTAWA AEROPLANE FLIGHT

Newspaper Aviator in His Way, Met With Some Difficulties

Up to the time of going to press the aeroplane bringing from Montreal the first copies of the Daily Mail, the new Montreal paper, had not arrived, the latest reports state it is en route.

MISHAP AT LACHINE

William Robinson, the aviator, starting with his monoplane [It was in fact a Lillie-Vought biplane-Ed] from Montreal at 9:40 a.m.. He got as far as Lachine, when the machinery went wrong, and he had to descend to fix it. He made another start about noon and later information was that he was making good headway towards Ottawa, and if nothing happened should land here between 2:30 and 3 o’clock.

He was expected to arrive at Lansdowne Park sharp at noon, where he wold be met by Mayor Ellis and other civic and government dignitaries to whom he would hand copies of the new paper.

BIG CROWD WAITED

The news of the novel attempt at delivering a newspaper from one city to another by aeroplane caused a good deal of interest throughout the city. About eleven o’clock the vanguard of a crowd that totalled several hundreds by 12 o’clock began to arrive at the park. Many came in motor cars. The street cars did a big business.

Mayor Ellis was on hand a little before noon, ready to welcome Robinson and receive a copy of the newest daily. Half a score of newspapermen, representing as many of the leading and long-established papers in the Dominion, were also there noticeably anxious to get a look at the latest rival. Several photographers posted themselves in different parts of the field ready to get a snap of the machine as soon as it began to descend on the football gridiron. Most of the crowd went home to lunch and returned later in the afternoon.

MISTY AT THE START

Robinson was ready to leave Montreal before nine o’clock this morning, but was prevented from doing so because of the thick mist hanging over the city and the surrounding countryside. There was quite a stiff breeze blowing at the time, which he did not like to face. However, by 9:40 he got away as the mist had cleared considerably and the wind had dropped.

Robinson was reported passing Hudson, 37 miles this side of Montreal, at 1:25 p.m. following the course of the Ottawa River

In addition to the front page article, the editors of the Citizen, in their comment section stated rather sulkily that

“Delivering newspapers by aeroplane is a capital initial advertisement, but one cannot help fearing it will fall down in due time to the somewhat doubtful service of the small boy, who has never yet met a successful competitor in this particular line of business. Hence the said small boy may regard the advent of the new method today with a curiosity untouched by fear for the tenure of his job.”

On October 9, 1913, a less effusive and perhaps jealous Ottawa Journal wrote a short piece and buried it on page 11 about the air delivery publicity stunt stating:

DELIVERS PAPERS WITH AEROPLANE

Premier Borden Receives Daily Mail by Aero Route.

The Montreal Daily Mail, the new paper which entered the field of Canadian Journalism yesterday, made its first Ottawa delivery by aeroplane about 5 o’clock last evening, when Aviator Wm. Robinson alighted in Slattery’s Field, Ottawa East, after flying from Montreal. The aviator had previously planned to land at Lansdowne Park in front of the grandstand, but owing to the lateness of his arrival he found a landing there would be impossible, as the fields was taken up by a football practice.

The aeroplane, which was due to arrive in Ottawa at noon yesterday, suffered an accident in Lachine, Que. soon after leaving Montreal, which forced Aviator Robinson to descend and delayed him two hours while necessary repairs were being made. The Ottawa bundle of papers contained fifteen papers, of which four were delivered to Premier Borden, Sir Wilfred Laurier, Sir Charles Fitzpatrick and Mayor Ellis respectively.

In addition, there was a one-sentence long comment in the editorial section which appeared to mock the Daily Mail’s bold stunt: The first issue of the Montreal Daily Mail, the new one-cent morning daily in the metropolis, looked quite bright yesterday. We don’t see why it broke the bird man down.”

In addition to the site plaque on the hydro station building, there is one other reminded of those heady days when the future came to Ottawa — a suburban street, appropriately near the Ottawa Airport, was named after that humble meadow and the events that took place there over 110 years ago. Photo: Dave O’Malley

After Robinson’s eventful flight, he booked a room at the Chateau Laurier with the intent to make exhibition flights over the next couple of days. The very next day, as the Ottawa Citizen reported, he lifted off from Slattery’s Field shortly before noon for an exhibition flight over the city and had just started to climb out when the Gnome engine “went wrong” and he was forced to land back at the field. In one account, his Lillie-Vought aeroplane was damaged in the landing.

Before Robinson’s flight to Ottawa, the Daily Mail had taken out a half page ad in the Montreal Gazette in which it stated that he would return by air to Montreal on the 9th and give demonstrations over the city, but there is no newspaper record that he did. There was then a brief mention in the Daily Mail on the 10th which stated that Robinson was slated to give a flying demonstration in Ottawa on Tuesday, October 14th and then pack up his aircraft to transport it back to Montreal for further flight demonstrations, but again, there is no record in the Montreal or Ottawa papers that indicates he did that. Despite Robinson’s promise to those who were disappointed at Fletcher’s Field, he does not appear to have returned by air or even train.

The Daily Mail would publish its pro-British newspaper in a French city for only four more years. They shut down their presses in August of 1917. Perhaps three years of Quebec men dying under the leadership of British general officers in the Great War in Europe had something to do with their demise. The paper did outlive Bill Robinson however. Like the boy aviator Peoli, he would die in the crash of an aeroplane of his own design.

While Robinson’s flight failed to bring enough attention to the Daily Mail to send it into the publishing stratosphere, it did mark a major milestone in the history of Canadian aviation. It was the first cross-country flight in Canada to link two provinces by air.

After his Canadian visit, would return to the American Mid-West, where, in his hometown of Grinnell, Iowa, he started up an aircraft manufacturing enterprise called The Grinnell Aeroplane Company. He designed and built two aircraft — a parasol monoplane called the Scout and a biplane. He also designed custom 6-cylinder 60 and 100 hp radial engines for his airplanes. A year after his flight to Ottawa, on October 17, 1914 Robinson would become the second officially appointed airmail carrier in the United States after setting a new American cross-country distance record travelling 390 miles in four hours and forty minutes nonstop in his Grinnell-Robinson Scout.

Robinson at Grinnell Iowa with the GrinnelI IIA monoplane (also called the Grinnell-Robinson Scout) that he designed and built in 1915, powered by a 60 hp radial engine of his own design, the first airplane to be built in that state. Photo: Child of Grinnell

Designed in 1915, while the rest of the world was at war, the Grinnell-Robinson Scout, never got beyond the prototype stage>

A top view of the Grinnell-Robinson Scout which appears to have no ailerons. Photo was probably taken from the roof of the Grinnell Aeroplane Company building after completion.

Robinson taxiing his Scout monoplane in the long grass near his Grinnell Aeroplane Company hangar/factory.

The Grinnell-Robinson biplane, Robinson’ second design. It must have been a relatively good performer as he took it to 17,000 feet.

At 3:30 in the afternoon of March 11, 1916 “Billy” Robinson took his newly completed Grinnell-Robinson biplane out of his hangar at Grinnell, Iowa airfield and climbed into the chilly air determined to exceed the existing American altitude record of 17,000 feet. Previously, he had climbed his Grinnell-Robinson biplane to over 14,000 feet and on this day he was determined to establish a new altitude record. As he climbed, he drifted southeast toward the town of Ewart.

Word of the record attempt had swept Grinnell and there were many townspeople and farmers watching him as he climbed higher and higher until he was a mere speck in the sky. As farmers stared into the cloudy sky over Ewart, they saw his “aeroplane flutter[ing] down from the sky like a falling leaf. It came in erratic swoops and dives as though some hand were trying in vain to regulate it. The plane landed with a resounding crash in a field near Ewart”.

Billy Robinson would die in the crash, his broken body removed from the wreckage of his biplane and laid out beside it while a photographer took a photo which would be the subject of a macabre postcard for sale. Also killed in the crash was any promise that the Grinnell Aircraft Company might have brought to the economic future of that Iowan town. Within a couple of years, the company shut down.

The voyeuristic Iowan postcard depicting the body of Robinson after his crash. Historic Iowa Postcard Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Grinnell College Libraries.

Sidebar

Six Degrees of Separation in the Pioneering Age

By 1913, there were hundreds of qualified pilots in North America and many shared a common aviation DNA. Max Lillie, who was involved in the development of Robinson’s airplane had also taught the Iowan to fly just a year before he made his historic flight. A Swedish-born entrepreneur, flying instructor and pilot, Lillie also taught Katherine Stinson to fly. She would make similar history in Western Canada in 1918 when she flew from Calgary to Edmonton (a distance of 300 kilometres) and make the first Air Mail flight in Western Canada.

Baby-faced Max Lillie (centre) is seen here (possibly learning to fly) in the company of another aviation pioneer, Bob Fowler (right), the first person to make an West-to-East transcontinental flight (In stages) which he started in September 1912 at San Francisco and completed 5 months later in February 1913. The man in the left is famed wrestler Frank Gotch. Photo: Wikipedia

Billy Robinson (left) learning to fly in a Wright Flyer in 1912 with instructor Max Lillie, a Swedish entrepreneur and early pioneer. Lillie partnered with fellow pioneer Chance Vought to create the aircraft that Robinson would use to bring the Daily Mail newspapers to Ottawa. Just a few weeks before Robinson’s flight to Slattery’s Field, Max Lillie died in an airplane crash in Illinois. One of Max Lillie’s notable accomplishments was that he taught Katherine Stinson to fly. She was just the fourth female aviator in America, but one who captured the hearts of Americans. She was also the first person to fly air mail to Edmonton, Alberta.

“Safe and Sane”! Max Lillie, the Swedish-American aviation pioneer used a photo of himself instructing Katherine Stinson in a Wright Flyer at Cicero Field in Chicago in this 1912 advertisement in Aerial Age, a very early aviation trade magazine. Image via Chicagology.com

Katherine Stinson was one of the most popular “aviatrices” of the early years of aviation, known as The Flying Schoolgirl”. She was the first woman to fly a loop in America and was the first woman to fly in both China and Japan. Unlike her instructor Max Lillie, she had a longer flying career as a stunt and mail pilot which she retired early from due to health reasons. She lived a relatively long life, died in 1977 and was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2019. A replica of the Curtiss-Stinson Special aircraft [not the aircraft in this photo] she flew on the first air mail flight in Alberta resides at Edmonton’s Alberta aviation Museum. For a wonderful video about Katherine Stinson, click here. Her success and fame in the air inspired her brother Eddie to create the legendary Stinson Aircraft Company.

Slattery’s field welcomed Billy Robinson who was taught to fly by Max Lillie who taught Katherine Stinson who brought the first air mail to Edmonton, Alberta. In the early days of aviation, there was but a few degrees of separation between the characters who gave us a start. Photo via New Mexico History Museum