LETTERS FROM HOME

We live in a world connected by electronic means of communication. It is indeed a blessing. But it is also a loss. Let me explain.

My wife and I stay connected to our son in London, England through Skype, FaceTime, smartphone texts and email. Without these electronic applications, I think Susan would go mad with worry. They keep us visually connected, emotionally at rest and they push back the darkness and uncertainty. Likewise, after dinner, we like to ring up our daughter in Hamilton, Ontario and spend a half-hour entertaining our mischievous and precocious 2-year-old granddaughter. These new ways for humanity to stay in touch with family provide emotional release and visible proof of the health and spirit of a son or daughter far away. But, there is also a downside.

Direct and visual connection with correspondents using electronic means such as Skype also erase the many benefits of the old-fashioned method—the handwritten letter. Gone or at least on the verge of extinction are simple things like elegant penmanship, careful forethought, poetic expression, hidden meaning, code, the ability to reassure family with words, the lipstick-kissed love letter held in a pilot’s inside pocket, the lock of hair, the small photo, the tear-stained ink.

Back in the middle uncertain years of the Second World War, the hope of an early end to the war and to be “home by Christmas” had long since left the heart of the fighting man in Europe, North Africa, and the Near and Far East. Parents, who last saw their uniformed sons and daughters boarding a train for an unknown future, lived out their lives in anguish, worry and stress back home. The handwritten letter, the perfumed note card, a scarf knit with love by Gramma, the box of favoured Baby Ruth candy from Mum—all carried with them a powerful message of security and hope.

During the Second World War, the fighting man, the rear echelon service battalion soldier, the ground crew airman, or field hospital nurse in a distant and strange land was desperate to hear from home, and to send letters back there assuring parents that they were safe and out of harm’s way. They took solace knowing that Dad had the crops almost in, that little brother Hugh was playing hockey with the hometown team, that Mum had learned to drive and that Sis had a good job at the factory making parachute harnesses. Knowing that life at home was still there, largely unchanged; that it would be there when they returned, was the one fact unblemished by the stress and horror of the war they were part of. Mail would be one of the great weapons of the fight, one of the unsung strategies that kept the Allied fighting forces from going insane. The Royal Canadian Air Force knew and understood this better than most.

Far from home, often lonely and missing family and sweethearts, soldiers, sailors and airmen alike looked forward to every mail call to find some connection with the life they had left behind. Here, airmen gather round a Flight Sergeant at mail call in North Africa, as he hands out parcels and envelopes—perfumed love letters, family updates, favourite cookies, knitted scarves, photos from home and a connection with a former life. Out of curiosity, I checked the fate of Vickers Wellington (HF795) in the background and learned that it was lost on operations 10 April 1943 when it was seen on fire before crashing near Sainte-Marie du Zit, Tunisia. Photo: RAF

In December 1943, after three years of bloody, dusty battle in North Africa, Canadian Army soldiers were slogging it out toe to toe with the Germans, bogged down in the small coastal town of Ortona in a vicious street fight that became known as “Little Stalingrad”. Royal Canadian Air Force pilots in Bomber Command were dying in droves every week, raked by night fighters and shredded by flak, yet were willing to climb back into that crew hatch one more time. Canadian sailors ran the U-boat gauntlet for the fourth straight year, freezing, forever wet and miserable. Letters from home—you can easily imagine the importance of them.

In early December, the Royal Canadian Air Force stood up 168 Heavy Transport (HT) Squadron at RCAF Station Rockcliffe here in Canada’s capital, overlooking the broad flow of the mighty Ottawa River. 168 Squadron had one task—get the mail to Canadians fighting in Europe and the Mediterranean, and get it there fast. Prior to 168 Squadron’s inception, most mail went by sea. It was not uncommon for a mother to get a telegram that her son was killed in battle, only to get a letter from him in the mail three weeks later, mailed months before. Soldiers needed the boost in morale offered by mail from home and the RCAF decided to build a force that could get it there fast.

The Commanding Officer of 168 (HT) Squadron was a highly experienced Canadian by the name of Wing Commander Robert Bruce Middleton, a Canadian who had a commercial license before joining the Royal Air Force from 1934 to 1936. Leaving the RAF, he was one of the early pilots of Trans Canada Airlines and then went to Imperial Airways in Great Britain, gaining experience flying long-distance night flights across water. When the war broke out, Middleton rejoined the RAF and conducted ferry and transport missions, before being selected to head 168

The first Atlantic crossing mail flight was flown by Wing Commander Robert Bruce Middleton, a native of Fort Francis, Ontario, and a highly experienced aviator and officer of the Royal Air Force. Middleton was the commanding officer of 168 Heavy Transport Squadron and piloted the first flight to Europe and North Africa. He is a member of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame. Photo: DND\

Related Stories

Click on image

The RCAF purchased six used Boeing B-17E and B-17F Flying Fortresses from the United States Army Air Force and ferried them to Rockcliffe—five over three weeks in December and the sixth in February of 1944. The Rockcliffe “Forts” were the only B-17s ever in the direct employ of the Royal Canadian Air Force and they were given the standard RCAF four-digit serial numbers common in the Second World War—a block of numbers from 9202 to 9207. Though the RCAF had never operated Flying Fortresses before, Canadians were no strangers to four-engine bomber operation. Canucks in Bomber Command were crewing Handley Page Halifaxes, Avro Lancasters and Short Stirlings, as well as B-24 Liberators and Sunderland flying boats with Coastal Command, and were flying in all B-17 crew positions, attached to Fortress units of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber and Coastal Commands.

When the first of these former training Fortresses arrived at Rockcliffe in the first week of December 1943, they were somewhat clapped out and still carried their defensive weapons, American markings and serial numbers. They underwent immediate changes that saw the removal of the features that earned them the name Flying Fortress—their machine guns. Flying across the Atlantic Ocean to places like Morocco, England, Egypt and Italy meant that the chance of being attacked over open water by a German marauder was negligible, and now, with North Africa secured by the Allies, the only enemy aircraft with the range to find them were also four-engined patrol bombers like the FW200 Kondor. Subtracting the weight of the machine guns, their turrets and the gunners meant more mail or additional fuel could be carried, thus increasing the effectiveness of each mission.

A quick look at this photograph allows us to pinpoint the date... if you know what to look for. The key to the time-stamp lies in the numeral “101” seen on the nose of this dark camouflaged Boeing B-17F. When RCAF Flying Fortress 9203 arrived at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in the first week of December 1943, it still carried its United States Army Air Force markings and serial—42-6101. The “101” on the nose is the “last three” of the former USAAF 42-6101. Given that the RCAF would have removed her American identity before her first Mailcan operation, this is likely the delivery flight to Rockcliffe and this is the Canadian ferry crew—Pilot, co-pilot, navigator and radio operator. The typical bitter cold December weather of Ottawa, Ontario is evident in this photograph, giving credence to the claim of the arrival of the ferry flight. Photo: DND

Before their inaugural flights could take place, each “Fort” had its American markings painted out and RCAF roundels and serial numbers applied to their sides. The first Mailcan Fortress flight, as they became known, was scheduled for the week after the arrival of the first B-17 (9202). The goal was to get as much mail as possible to the front before Christmas, and bring an equal amount of letters to worried families back home.

For the weeks leading up to the arrival of the B-17s and the first flight, letters and packages for troops overseas were channelled by Royal Mail Canada to Ottawa. Trains arriving from Montréal and Toronto puffed and screeched along the Rideau Canal and clanked to a stop at Union Station, across from the Chateau Laurier Hotel. Mail car doors rattled open while railway employees tossed white bags labelled “Canada P.O.” onto heavy wooden trolleys. These were pushed across the street to Postal Station A (since demolished and turned into a shopping centre), sorted for destinations and transported by RCAF truck the 8 kilometres to RCAF Station Rockcliffe. Here, a photo-op was managed for the benefit of the press. In a rather stagey photograph taken in the poorly lit confines of 168 Squadron’s hangar at Rockcliffe, a large heap of mailbags were seen being checked on the manifest by a well-turned out Flight Sergeant, while Military Policemen with holstered pistols watched with stern faces.

Another photograph, taken out on the snowy ramp, depicted no less than 14 airmen unloading a truck and bucket-brigading the mailbags into the starboard waist gunner’s window at the rear of the fuselage. The first B-17 to be ready to fly the mail to Canadian servicemen overseas was 9202, but at the last minute it acquired a snag and went unserviceable. Flying Fortress 9204 was then selected as the alternate for the inaugural flight.

An RCAF Flight Sergeant checks his manifest as an airman stacks Canada Post Office mailbags under the watchful and mistrusting eyes of a pair of armed guards. The diagonal siding of this structure indicates that the photo was taken indoors in one of Rockcliffe’s flightline hangars. Photo: DND

Airmen unload a truck-full of mailbags and feed them through the waist gunner’s window in the fuselage of a 168 Heavy Transport Squadron “Fort”. The weather is decidedly December in Ottawa, leading me to surmise that this photo op was set up for one of the first Mailcan flights to Europe to help promote the new mail service. Lending credence to the idea that this is an image of the inaugural flight for this aircraft is the fact that the roundel is clearly freshly painted. Had this aircraft had just one flight across the Atlantic and back, the paint would have been in rougher shape. Also, there are 14 airmen in a bucket-brigade-style loading, which, to me, seems overkill for the work required, but perfect to show the manpower the RCAF was throwing at the project. The Flight Sergeant with the clipboard is the same fellow from the previous photo. In the distance, we can clearly see the administration building for the seaplane and amphibian base along the Ottawa River, and beyond that we see the smokestack of the pulp and paper plant at Pointe-Gatineau, Québec across the river. Photo: DND

The end result. A Canadian soldier at an airfield near Foggia assists the unloading of the first flight of airmail for Canadian soldiers in Italy—from a 168 Squadron, RCAF Boeing B-17 aircraft on 30 December 1943. Photo: DND

Though this was not a combat operation, this was no place for junior or inexperienced crews. The mail was important, and so, highly experienced aircrews with combat and transport experience, lucky to survive tours in Bomber Command, were selected to crew the “Forts”. The first flight, departing Rockcliffe on 15 December, was flown by Wing Commander Middleton himself. Later, 9204 was joined by the five other Flying Fortresses, some of which were stripped of paint and modified with faired aluminium noses which opened downward to access forward cargo space, as well as other improvements inside and out.

The first flight was not without problems. As Middleton approached Ireland, fuel feeding problems forced the B-17 to land at RAF St. Angelo near Enniskillen in Northern Ireland. Pressing hard to get the mail to troops before Christmas, and being new with Fortress maintenance, mechanics had failed to connect the auxiliary tanks to the main system. Despite the problems, 9204 carried 5,500 lbs of mail and two passengers to Europe.

On 15 December 1943, Fortress 9204 had the honour of being the first Boeing B-17 to take off on an operational mission in the employ of the Royal Canadian Air Force. It was filling in for 9202 when that “Fort” went unserviceable prior to the inaugural mail flight across the Atlantic, bringing Christmas parcels to Canadian fighting men in North Africa and Europe. On this first of many Mailcan flights, 9204 flew with two passengers and 5,500 lbs of Christmas mail. More than a year before being taken on strength with 168 Squadron, RCAF B-17F Flying Fortress 9204 was built under license by Douglas Aircraft at Long Beach, California for the United States Army Air Force as 42-3369. This Fortress did not last a year with 168 Squadron, having suffered unknown Category A damage at Rockcliffe in September of 1944. Photo: DND

Somewhere in Europe, 168 Heavy Transport Squadron’s Flying Fortress 9204 unloads its payload of mail to an awaiting truck. In the earlier photograph it appeared it took 14 men to load the Boeing, but it seems five will do for the unloading. Looking forward along the top of the fuselage, we can see the circular discolouration where the “Fort’s” original top turret has been removed, faired over and painted. As well, we see the insert and window where the waist gunner would have stood, and if you look really closely, you can make out the area around the roundel where the old USAAF “Star and Bar” markings were painted out. The Fortresses of 168 Squadron had their guns removed to save weight and because they were thought safe from attack flying from Ottawa to England or North Africa. Photo: DND

Drawings of two of 168 Squadron’s B-17s show model makers the specific colours for painting their aircraft. We can see 9204 at top in the same paint scheme she wore in the previous photograph, while at the bottom we see 9205 in the bare metal finish that the last of the “Forts” were wearing at the end of their short but productive service life. Here we can see that 9205 had a black anti-glare panel on the forward fuselage. Diagram for plastic modellers (source unknown).

From the first flight onward, 168 Heavy Transport Squadron B-17s settled into a steady service back and forth across the Atlantic, bringing the mail to our warriors in Europe and North Africa. Fortresses and Liberators would carry the mail back and forth across the Atlantic, while seven DC-3 Dakotas (a detachment of 168 Squadron was based at Biggin Hill, England) would distribute the mail across European destinations. In the first month of operations alone, 168 Squadron Fortresses and Liberators carried 111,600 lbs of mail. In late January of 1944, the service was extended from Prestwick (Scotland) to Gibraltar, Algiers (French Algeria), Foggia, Bari, Naples (all in Italy) and Cairo (Egypt). As 1945 rolled around, mail service was six times a week. Another weekly flight was added in April 1945, making it a daily service. Refuelling stops on the northern route were Reykjavik (Iceland) and Goose Bay, and on the southern route, Lagens in the Azores or Bermuda. Every nook and cranny of the aging aircraft was stuffed with mailbags. When the war was over, they continued to fly mail and relief supplies to war-torn Europe.

But despite the lack of an enemy air force to threaten the Fortresses, these mail flights proved a deadly serious business. Three of the six B-17s were lost in tragic accidents that killed their highly experienced crews, and two others were heavily damaged. Of the six “Forts” held by the Royal Canadian Air Force, only two survived to be disposed of by War Assets.

The near loss of a crew and Fortress happened almost immediately. Upon receipt of Fortress 9205 in the middle of December 1943, the official Royal Canadian Air Force assessment was that the aircraft was “very dilapidated, all the parts being badly worn.”

Regardless, maintenance crews struggled to make it mission-ready. On 23 January 1944, Fortress 9205 was flying from Prestwick to Gibraltar when it was involved in a mid-air collision with an RAF Wellington in fog over the Bay of Biscay. The collision left the Fortress with extensive damage to the nose, wings and tail and two engines were forced to be shut down and their props feathered. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant Horace Hillcoat, turned back to Prestwick, and made a safe landing on the remaining two engines (one without a supercharger), but the crew was forced to jettison the load of mail.

A piece in the Winnipeg Tribune, dated 14 March 1944, reported the dramatic incident aboard Hillcoat’s Fortress:

“The crew of a Canadian Flying Fortress mail plane lived through an aerial nightmare when it collided in a Biscay Fog with a heavyweight Wellington. With only one engine ticking, the Fortress brought its crew back to base. In an amazing aerial exploit, the crew of an R.C.A.F. Flying Fortress recently nursed their crippled aircraft back to safe landing in the United Kingdom with only one motor functioning after a mid-air collision with a Wellington bomber over the Bay of Biscay.

R.C.A.F. headquarters said today all that remained of the Wellington after the crash was bits of wings and ailerons later found embedded in the body of the Fortress. On the day of the crash only two aircraft were known to be operating over the bay – the Fortress flying mail to Canadian forces in the Mediterranean and the coastal command Wellington (JA268) on patrol. Both were flying on instruments and taking advantage of cloud cover. They met at 5,000 feet. There was a flash of flame, a grinding jar as the Fortress seemed perceptibly to stop in mid-air. F/O. H.B. Hillcoat of Moose Jaw, Sask., and his crew tensed for a crash into the sea.

Through the cloud, lighted by fire from one of their engines, they saw the shadow of an aircraft hurtling down to the water. A second later the Fortress was spinning down after it. The crew jettisoned everything movable, including mail, as the pilot wrestled with his controls. Then, at 1,200 feet, the stricken aircraft levelled off and staggered ahead, barely under control. The outer port engine alone was developing anything like normal power. Fighting stubborn controls, Hillcoat set course for Britain. The ‘Fort’ limped through the murk. Finally, Hillcoat set her down in a semi-blind landing. The navigator, F/O. F.B. La Brish, of Regina, ran around to the nose, within which he had been sitting at the moment of the collision. He looked up at the hole where the metal ring of the gun port had been. The ring had been hurled by the Impact past La Brish’s head and was embedded in the partition behind where he had sat. That, he concluded, was what had ripped off his helmet and earphones.”

The Ottawa Journal on the same day described the impact and recovery of the Fortress as “one of those million-to-one-chance affairs... one of the most amazing aerial exploits of the war.”

Hillcoat’s citation for his award of an Air Force Cross states: “This officer was captain of a Fortress which was proceeding one night recently from Great Britain to Gibraltar, when about 190 miles from base, under very dark conditions in cloud, his aircraft had a violent head-on collision with an unidentified aircraft on 23 January 1944. Despite the fact that two engines were out of commission, all four propellers bent and the aircraft badly damaged, he managed to right it, after falling approximately 2,000 feet. When they were still unable to hold altitude, he directed his second pilot and crewmen to jettison the cargo and all other loose equipment. By strenuous effort and skillful flying, he was able to set course for land. Although flying with a crew previously unknown to him, he guided their efforts with such confidence that every member performed his function in a most exemplary manner. The flight back occupied approximately two hours of instrument flying, during which the aircraft was vibrating terrifically and apparently on the verge of breaking up. By careful use of radio and other aids, an aerodrome was found and a successful landing was made with no further damage to his aircraft. This officer, when faced with an almost unprecedented emergency in the air, did his job and directed his crew in an extremely laudable manner.”

The navigator on the flight was Flying Officer Frederick La Brish of Regina, Saskatchewan. His Air Force Cross citation for his professionalism during the incident states, in part: “The navigator’s compartment was badly damaged but Flying Officer La Brish quickly gained his full senses and immediately moved aft to the wireless compartment, where he carried on his duties in a very cool and efficient manner, despite having to work on the floor under extremely awkward conditions. That the aircraft successfully completed the return trip in its badly damaged condition is in great part due to this officer’s expert knowledge and coolness under most trying circumstances.”

The Wireless Operator was Flying Officer Cecil Dickson and his citation states, in part: “In spite of the fact that the aerials and loop were missing, he successfully maintained contact with shore installations, and his co-operation with the navigator under extremely trying conditions contributed to a great extent in the safe return of the aircraft to base.”

Also on the flight were Flying Officer Eli Maximillian “Ross” Rosenbaum (30 years) and crewman Corporal A. DeMarco. Rosenbaum’s obituary in 2001 stated: “Eli and the entire crew were awarded the Air Force Cross on May 5, 1944. Eli always joked about having received a medal for saving his own life... From then on, Eli considered his life to be a gift, and he lived his life as though it were indeed a gift to be savored daily, laughing, joking, hugging, always singing and whistling - just happy to be alive.”

Fortress 9205 was then fitted with a temporary fabric nose and upon return to Ottawa, was fitted with the fold-down metal nose cone. But 9205 was a hard luck bird. The following November it made a wheels up landing at Rockcliffe, was repaired and then again in April of 1945 suffered category C damage in the Azores. Luckily, 9205 made it through the war without any more damage, and, after delivering relief supplies to Warsaw, Poland, left 186 Squadron to become a Search and Rescue aircraft. In 1964, 9205 was sold to the Argentinian civil registry as LC-RTP. Horace Hillcoat, Fred La Brish and Cecil Dickson did not fare so well, as we shall see.

Flying Fortress 9205 survived her many brushes with death, and was one of only two to survive the war and subsequent relief efforts. Here we see 168 Squadron airmen loading penicillin and other relief supplies prior to heading to Prestwick and Warsaw. Photo: DND

There are few photographs available of Fortress 9207, the last of the six, which arrived at Rockcliffe at the start of February 1944. Perhaps it is because she lasted only three months. Just 12 weeks later, on 2 April 1944, 9207 was taking off from Prestwick, bound for Canada. Witnesses saw the Fortress lift off and then climb out with increasing steepness until it stalled and, still under full power, spin out of control and crash into the ground. The “Fort” was completely destroyed by the impact and ensuing fire and the five Canadians on board were killed instantly. The post crash investigation had no definitive cause for the crash but investigators suggest that its cargo of mail had shifted in the steep climb, moving the centre of gravity aft. One just has to view the video of the same thing happening to a Boeing 747 at Afghanistan’s Bagram Airfield to see the devastating effects of a load shifting on take-off. 9207 did not have the mail restraint modifications later installed on the other Fortresses.

Five months later, on 17 September, 9204 suffered Category A damage at Rockcliffe. The Fortress had just landed after a long flight from Prestwick. As the Fortress was taxiing along the Rockcliffe flight line, the undercarriage collapsed, seriously damaging both outer Pratt and Whitney engines and slightly damaging the inner pair. Category A damage is described as “destroyed, declared missing or damaged beyond economical repair.” The damage was serious enough to take the Fortress out of the lineup for good. It was struck off charge on 11 October and parted out. No injuries or fatalities were reported.

Tragedy struck again on 15 December 1944. Boeing B-17 9203, one of the hardest working “Forts” in the fleet, disappeared while on a transatlantic flight from French Morocco to Canada via the Azores. The highly experienced crew, including pilot Horace Hillcoat, and three RCAF pilot passengers never arrived in the Azores. Only a few Royal Mail Canada mailbags were spotted floating on the surface during the search. 168 Heavy Transport Squadron had now lost half of its Fortress Fleet, just one year into operations.

Losing another “Fort” was bad enough, but it was the human loss that truly devastated the squadron. Five of its airmen and three of its passenger charges disappeared into the Eastern Atlantic swell. These were no ordinary pilots and aircrew. Between the two pilots, there were two Distinguished Flying Crosses (DFCs), one Air Force Cross (AFC), Air Force Medal (AFM) and a Dutch Flying Cross. The navigator had an AFM as well. Among the passengers, Flight Lieutenant William Pullar was also a DFC recipient.

168 Squadron pilots swing their Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress 9203 around on the ramp at RCAF Station Rockcliffe, loaded with mail for Europe in the summer of 1944. A close look at the photograph shows she is stuffed with mailbags, filling the Perspex nose and visible through the starboard side cheek gun port. Fortress 9203 was built for the USAAF in 1942 as 42-6101. For a full year, she lumbered back and forth across the Atlantic on mail runs, but met a tragic end somewhere between Morocco and the Azores in December of 1944. She was last seen on 15 December taking off from Morroco with mail, five crew members and three passengers. No traces of the Fortress were found save a few floating mailbags. The dead included Flight Lieutenant Horace Hillcoat (pilot) of Ottawa, Flight Lieutenant Alfred John Ruttledge (co-pilot) of Simcoe, Ontario, Flight Lieutenant Frederick La Brish (navigator) of Regina, Flying Officer Cecil Dickson (wireless operator) of Edmonton, Alberta, Corporal Robert Bruce (aircrew/loader) of Victoria , British Columbia and passengers William Pullar (pilot) of Delta, Alberta, Douglas Sharpe (navigator) of Montréal and William Wilson (admin) of Chatham, Ontario, all Flight Lieutenants. It is interesting to note that the B-17’s crew was comprised of highly seasoned and experience multi-engine airmen. Hillcoat, 31, had an Air Force Cross and Air Force Medal. Ruttledge, 30, had 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses and a Flying Cross from the Netherlands and La Brish an Air Force Cross. This was clearly a crack crew. Even passenger Pullar, a Bomber Command pilot had a DFC. Sadly, it is likely that the passengers were returning home after completing their tours. Photo: DND

The previous photograph was actually a cropped copy of this image, forwarded to us by Jim Bates. Here, at Rockcliffe we see a Westland Lysander target tug in bright yellow and black “Oxydol” paint scheme and an Avro Anson. Photo: DND

When Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress 9203 was lost over the Atlantic, Canada lost some of its most decorated and experienced flying heroes. I tried to find images of all eight men who were lost, but managed to find photos of only these four men. Clockwise from upper left: Flight Lieutenant Frederick La Brish, AFC; Flight Lieutenant Horace Hillcoat, AFC, AFM; Flight Lieutenant William Pullar, DFC and Flight Lieutenant John Ruttledge, DFC and Bar, Flying Cross (Netherlands). Photos via Veterans Affairs

Hillcoat’s co-pilot on the doomed flight, Flight Lieutenant Alfred John Ruttledge of Simcoe, Ontario, was even more experienced and his loss dramatically underscored the dangers of the long over-water flights and the unfairness of war. Ruttledge was a distinguished and highly decorated veteran. An article in his hometown newspaper, the Simcoe Reformer, reported that Ruttledge had completed 103 bombing missions over Nazi-occupied Europe, 3 full tours of flying operations and 719 hours of combat flying.

Ruttledge was awarded a rare (for a Canadian) Dutch Flying Cross for his operations over that country. His citation reads: “Over a period of twelve months this officer completed six sorties of a special nature over Holland. He fully appreciated the very great hazards involved, but by the display of the highest degree of resolution, skill and leadership he set a most inspiring example to his contemporaries, and made a very fine contribution to the air effort in Holland.” When asked about his success after his return to Canada with two DFCs and a Dutch Flying Cross, Ruttledge told the Reformer reporter that he was “Just darn lucky”.

At the end of the Second World War, only three Fortresses (9202, 9205 and 9206) had survived. Sadly, that number was cut to just two a few months later, when B-17 9202, the first of the B-17 acquisitions of the RCAF, was lost on a mission of mercy. The aircraft was the same one that had fulfilled the first mission of mercy. 9202 left Ottawa on 31 October 1945 with 39 cases of much needed penicillin. It arrived at Prestwick the following morning, fuelling and then flying on to RAF Manston, England. Two days later on 4 November, 9202 left Manston bound for Warsaw via Berlin, Germany. Around noon the big Fortress, flying low in cloud, struck trees at the top of a high point near Halle, Germany known as Eggeberg Hill. The five Canadians on board were killed instantly as the “Fort” struck the ground, disintegrating and bursting into flame. All were buried in Münster, Germany

Under the watchful eyes of an officer, a Leading Aircraftman paints a mailbag mission marking on the nose of Fortress 9202, celebrating its fifth Mailcan mission across to Europe and back with the return mail. Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress 9202 was originally built for the United States Army Air Force as USAAF serial number 42-3160. It was taken on strength with the RCAF on 4 December 1943. It arrived at RCAF Station Rockcliffe still wearing its American markings and was assigned along with five more, soon-to-arrive Fortresses, to 168 Heavy Transport Squadron. The goal was to get the upcoming Christmas mail to Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen overseas as quickly as possible. However, Fortress 9202 went unserviceable at the last minute and the honour of the first flight went to another recently arrived Fortress, 9204. Fortress 9202 finally got back on line and was soon flying to North Africa with a belly full of mail on 22 December—just in time for Christmas. Photo: DND

An image of Fortress 9202 at Rockcliffe showing 16 mailbag mission markings on her nose, indicating trips across the Atlantic. Photo: DND

A rare colour photo of a 168 Heavy Transport Squadron Fortress (9202). By this time, 168 had made some improvements to the Fortress to make it more suitable to the task of transporting the mail and passengers—this included fold-down nose cargo access and removal of paint overall. The weight savings on the paint meant that several hundred pounds more of mail or fuel could be carried or the range extended accordingly. In this photo we can see a member of the ground crew relaxing in the pale sun of late winter as he fuels 9202. The massive tail of the B-17F is clearly seen in this shot. Photo: Etienne du Plessis, Flickr

168 Heavy Transport Squadron learned a lot from their experience bringing mail back and forth across the Atlantic. Ground crews stripped paint to lighten the aircraft, and maintenance people modified the nose of the B-17 to fit a hinged fairing to allow the valuable space in the nose to be stuffed with the mail. Here, ground personnel swarm one of the Fortresses preparing it for her next flight. Judging by the other “Fort” in the background and the clearly North American-style trash bin in the foreground, this is likely at Rockcliffe on a sweltering summer day and a rare photo of 168 Squadron when it wasn’t snowing or freezing. We know that 9202 and 9205 (and possibly others) were in bare metal finish and both were involved in transporting penicillin and other medications to Warsaw in November of 1945. It was 9202 that crashed, killing the crew of five. The man standing at the top of the Fortress is LAC Clarence Seifried of Guelph, Ontario. He had an interesting story to tell about one delivery flight to Great Britain. His son Wayne fills us in: “One of the best stories he tells is the one where a plane carrying cigarettes from Canada was flying into the UK and its landing gear would not lock down (or could not confirm they were locked down from the cockpit). The plane dropped its load on the airfield by opening the bomb bay doors to lighten itself before landing. All of the field crew scrambled to grab the “free” cigarettes! Needless to say a search was done of barracks later that day to recover the load! The plane landed safely!” Photo: DND

A photo of Fortress 9205 running up its engines at Rockcliffe with what appears to be a newly installed nose cone for easy loading of mail. This image depicts the ultimate configuration of a 168 Heavy Transport Squadron Flying Fortress. I suspect that this photo and the previous image, as well as the image of 9203 taxiing (further above) were taken on the same day. Photo: DND via Jim Bates

168 Squadron Fortress 9206 sits tarped against the elements on the grass at Rockcliffe. Arriving on strength at Rockcliffe December 21st of 1943, she was one of only two Forts to survive service with the unit. By war's end, it was in bare metal finish with the hinged nose with the two letter code “QB”. Photo via Jim Bates

Using a set of air stairs, RCAF airmen at Rockcliffe load boxes of Red Cross penicillin and other medications destined to help the people of Warsaw, Poland avoid famine in October and November of 1945. Once again, there is evidence of snow on the ground at Rockcliffe, not unknown for early November, but not unheard of either. Here we get a good close-up of the 168 Mail Squadron crest—a bald eagle holding two mailbags on a circle of light blue. We also see the simplicity of the fold-down nose cone for getting packages into the forward compartment. In the background, we see a Consolidated PBY Canso and several Ansons. The Fortress in the photo is identified as RCAF 9205 (Formerly USAAC 41-9142) Photo: DND

In addition to the B-17s, 168 Squadron also operated eight Consolidated B-24 Liberators on the same mission. Here 168 ground crew are seen loading mail in a typically cold Rockcliffe scene. Photo: DND

The five-man crew consisted of Flight Lieutenant Donald Forest Caldwell of Ottawa (32 years – pilot), Flight Lieutenant Edward Harling of Calgary, Alberta (28 years – co-pilot), Sergeant Edwin Phillips of Montréal (24 years – engineer and loader), Flight Lieutenant Norbert Roche of Montréal (radio operator) and Squadron Leader Alfred Ernest Webster, DFC of Yorkton, Saskatchewan (36 years – navigator).

When the navigator, Squadron Leader Alfred Webster, was awarded a DFC, his citation read: “[his] work as a navigator has been outstanding and only equaled by his courage. On one occasion when his aircraft was attacked by enemy fighters and the wireless operator badly wounded, he coolly and effectively administered first aid. Although handicapped by a damaged chart table, chair and instruments he navigated the aircraft safely back to base. He again displayed exceptional coolness and imperturbability, when his aircraft struck the trailing aerial of another which smashed the front turret and tore his clothes. Owing to his determination and resourcefulness, Flight Lieutenant Webster has several times been able to navigate his badly damaged aircraft back to base.

Engineer and loader Sergeant Edwin Erwin Phillips of Montréal had an interesting back story. Phillips was one of a small group of black Canadians in the RCAF. The Veterans Affairs Canada website included a short profile on Phillips, which reads: “Edwin Erwin Phillips was born in Montréal and worked as a printer’s apprentice before volunteering for service with the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942 during the Second World War. Only 21 years old when he enlisted, he would go on to work as a mechanic with the No. 168 Heavy Transport Squadron and rise to the rank of sergeant. As part of his duties, Phillips would sometimes accompany transatlantic cargo flights.

Prior to leaving on their mercy flight to Europe, the crew of Flying Fortress 9202 assembled at the tail for a photograph—likely the last taken of these men alive. Left to right: Flight Lieutenant Norbert Roche, Squadron Leader Alfred Webster, Flight Lieutenant Donald Forest Caldwell, Flight Lieutenant Edward Harling and Sergeant Edwin Erwin Phillips. Photo: DND

Sergeant Edwin Erwin Phillips enlisted in the RCAF in 1942. Being black in the RCAF may have been rare at the time, but a number of black Canadians served with high distinction, including Phillips who was completing his eighth crossing of the Atlantic. Units and squadrons of the RCAF were not segregated as they were in the USAAF. His and the service of other African Canadians is celebrated on the Veterans Affairs website. Photo via Veterans Affairs

The loss of Phillips and his fellow crew members was a devastating blow to the tight-knit squadron. Though their aircraft rarely flew together and were always in distant locations overseas, the men prided themselves with their accomplishments and the quality of their crews. The remaining Fortresses (9205 and 9206) were both struck from the RCAF lists a year later and sold to the civil registry in Argentina. They were both reported scrapped in 1964.

Former RCAF Flying Fortress 9206 is seen in a very poor scan from a publication as the Argentine LV-RTO, prior to her eventual scrapping in 1964. 9206 was flown to Morón, Argentina in 1948, to be used as a VIP transport. After that, a legal dispute had her grounded at Morón (above) from 1949 to 1964. Prior to her RCAF service, this B-17 (USAAF serial 41-2438) flew missions from Hawaii, then was sent to Australia, flying combat missions based at Mareeba Airfield. On 23 June 1942, while with the 19th Bomb Group, and flown by Frederick Eaton on photo reconnaissance mission over Rabaul, British Papua New Guinea, it was attacked by nine Japanese fighters, but managed to return—with damage to the wings. When the 19th Bomb Group began leaving Australia in October 1942 41-2438 was reassigned to the 93rd Squadron for the flight home. It remained in the 93rd as a trainer at Pyote, Texas. In January 1943, one B-17 from each of the 19th’s four squadrons was sent to Kirtland for the filming of Bombardier. 4102438 was one of the four. It was truly one clapped out “Fort” when it arrived in Ottawa. Photo: via AeroVintage.com

While Fortress 9206 was the last of the Mailcan flight Fortresses when it was scrapped in 1964, it can still be seen today in reruns of the Hollywood propaganda feature called Bombardier, starring matinee idol Randolph Scott and Pat O’Brien. The movie trailer held the promise that you would see Tokyo Bombed... before you very eyes!! The film was actually nominated for an Academy Award for special effects, and was shot at Kirtland Army Airfield in New Mexico. Poster: RKO Pictures

Whilst 168 was operating the Flying Fortresses, it also operated eight Convair-built Consolidated Liberators for Mailcan flights. These aircraft proved incredibly reliable and had a higher capacity for freight. “Libs” accounted for the lion’s share of lifting, accounting for nearly 400 of the Atlantic crossings, all without loss of life. In all, 168 transport aircraft flew 636 times across the ocean. Of these flights, 240 were made by the small fleet of six Flying Fortresses. In Europe, 168 Squadron pilots used DC-3s to do short distance delivery of the mail. With all types of aircraft, Middleton’s 168 Squadron flew 26,417 flying hours and carried 2,245,269 pounds of mail, which included 9,125,000 letters from home and from the front. In addition, the squadron also carried 2,762,771 lbs of freight and 42,057 passengers.

The total weight of cargo, the number of letters, the tally of crossings, the distances and hours flown, tell only half the story. One cannot quantify the greatest of all the accomplishments achieved by the crews and Fortresses of 168 Squadron, for it is as intangible as a knowing smile, a feeling of warmth, or a tear shed in joy. The mighty Mailcan “Forts” and their war hero crews brought news from home, the fragrance of love letters, the renewed hope for reunion, a strengthening of bonds stretched to the extreme, and the knowledge that the home front was still there, that the chaos and horror of Europe could be left behind if a man was to survive. I know in my heart that the men who flew the 168 Heavy Transport Squadron Fortresses understood this well and that their accomplishment brought them great joy. Sadly, they risked and, in some cases, forfeited all to bring our boys letters from home.

I can see them now—Hillcoat and Ruttledge—sitting relaxed in the front of their Flying Fortress, climbing out of Rabat, Morocco, heading west once again to the Azores, the sun shining in through the glass, the four big Wrights thundering, the blue Atlantic off the African coast 10,000 feet below. They chat, they laugh, they conduct their complex business as professionals. Perhaps they are talking about the progress of the war, the fact that it may soon be over. Perhaps they are talking about friends they have lost. Inside, despite the risks of the flight they are undertaking, they are both no doubt relieved that they are headed home to Canada, that they do not have to fly in combat again. All is good. They are returning to their families.

We leave them there, out over the Atlantic where, for ever more, they are young and beautiful and heading home.

By Dave O’Malley

A print of a hand lettered poster showing the Headquarters command structure for 168 Heavy transport Squadron – created before the Fortresses arrived. This image cme from David Russell, one of our contributors, whose father Arnold Russell served with 168 Squadron throughout the postal service. Image via Russell family archive

Another very evocative artifact – the entire aircrew strength of 168 HT Squadron, the “Flying Postmen”. Those mentioned in this story are Horace Hillcoat (top row, 4th from left), Eli Rosenbaum (4th from Left, Second row down). Fred La Brish (5th from left, third row down), Cecil Dickson (second from right, 4th row down), Edwin Phillips (2nd from left bottom row) and A. Demarco (second from right, bottom row). Note the last photo of the squadron mascot - a Dalmatian known as “Stupid”. Image via Jane Oltmann Ellis

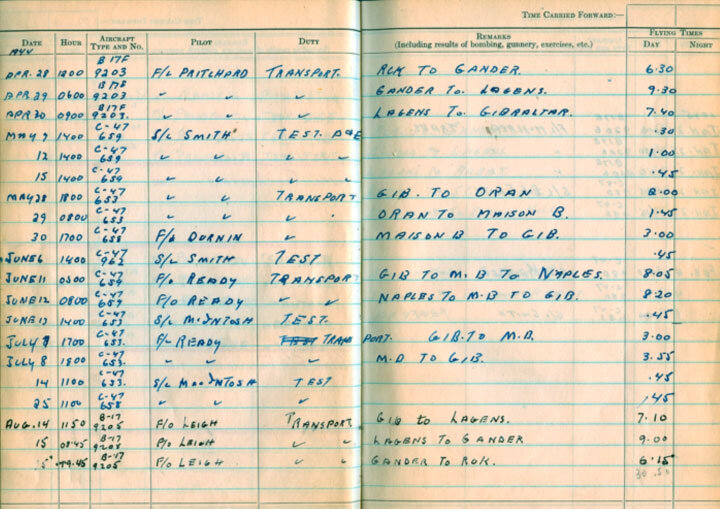

A page from the log book of then-Warrant Officer Arnold George Russell, showing typical routing of the B-17 Mailcn flights. Russell's son Dave, states: “After some experimentation with routing it was decided to use a southern route through the Azores – rather than over the North Atlantic. As you know, Lagens is in the Azores. The C-47’s were used to transport the mail from Gibraltar. or Rabat to the troops moving up through Italy while the Forts, on arrival in Gib. or Rabat, off-loaded then loaded mail for Canada and returned within 24 hours.” Image via Russell Family Archive

Here we see Arnold Russell (right) and other members of 168 HT Squadron, probably taken in Gibraltar or Rabat Sale Morocco (he and 168 was stationed in both places) or perhaps Naples where he flew on occasion. This was probably taken in 1945. Wing Commander Fraser (CO at the end of the war) commented on Arnold's skill and dependability, saying: “... [Russell] has completed a very excellent job of setting up our overseas Detachment at Gibraltar and who also maintained 100% serviceability for almost 5 months overseas” . Writing home to his wife, Russell spoke about the challenges of the older Fortresses: “Just a note in a hurry again. Another a/c arrived last night, -----I am still busy on 9205 lots of trouble and expect to have it cured today if lucky. Had to go to Port Lagustey [sp] yesterday afternoon for spares, quite a trip by jeep, about 60 miles roundtrip. Nice country but old looking. We were back at 5 o’clock and no spares”. Photo: Russell family archive

Here we see Arnold Russell (right) and other members of 168 HT Squadron, probably taken in Gibraltar or Rabat Sale Morocco (he and 168 was stationed in both places) or perhaps Naples where he flew on occasion. This was probably taken in 1945. Wing Commander Fraser (CO at the end of the war) commented on Arnold's skill and dependability, saying: “... [Russell] has completed a very excellent job of setting up our overseas Detachment at Gibraltar and who also maintained 100% serviceability for almost 5 months overseas” . Writing home to his wife, Russell spoke about the challenges of the older Fortresses: “Just a note in a hurry again. Another a/c arrived last night, -----I am still busy on 9205 lots of trouble and expect to have it cured today if lucky. Had to go to Port Lagustey [sp] yesterday afternoon for spares, quite a trip by jeep, about 60 miles roundtrip. Nice country but old looking. We were back at 5 o’clock and no spares”. Photo: Russell family archive

Clarence Seifried (second from left in front row) and members of 168 Squadron pose for a group photo outside their Nissen hut at Rabat. Cold weather of hot, the Nissen was inadequate in every way. Photo via Clarence Seifried

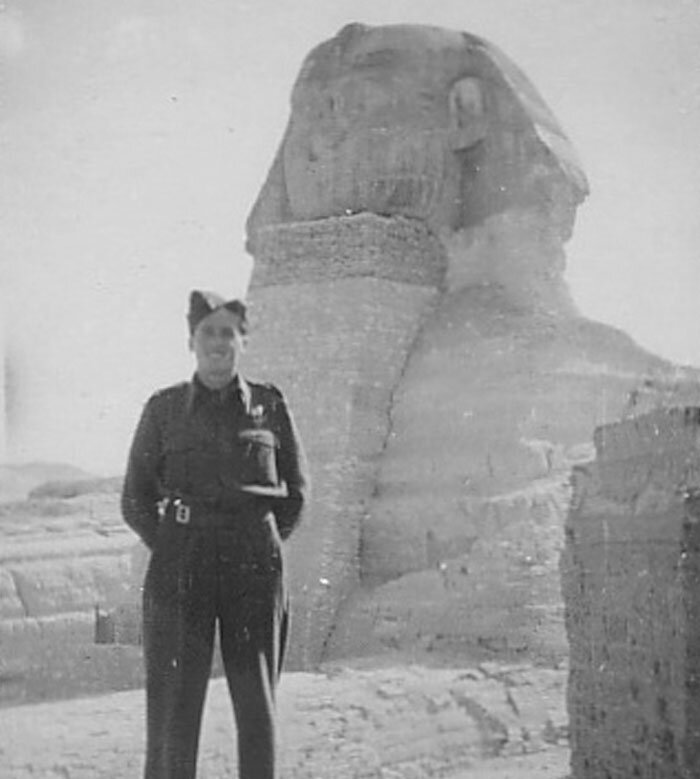

A photo of LAC Clarence Seifried in front of the Sphinx, probably during a milk run with the mail from Rabat to Cairo, then on to Paris, France and finally Biggin Hill. Photo via Clarence Seifried

![Here we see Arnold Russell (right) and other members of 168 HT Squadron, probably taken in Gibraltar or Rabat Sale Morocco (he and 168 was stationed in both places) or perhaps Naples where he flew on occasion. This was probably taken in 1945. Wing Commander Fraser (CO at the end of the war) commented on Arnold's skill and dependability, saying: “... [Russell] has completed a very excellent job of setting up our overseas Detachment at Gibraltar and who also maintained 100% serviceability for almost 5 months overseas” . Writing home to his wife, Russell spoke about the challenges of the older Fortresses: “Just a note in a hurry again. Another a/c arrived last night, -----I am still busy on 9205 lots of trouble and expect to have it cured today if lucky. Had to go to Port Lagustey [sp] yesterday afternoon for spares, quite a trip by jeep, about 60 miles roundtrip. Nice country but old looking. We were back at 5 o’clock and no spares”. Photo: Russell family archive](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1626138587018-W43AEB1APYO42M51Z9P4/F4134D48-269E-4080-B310-613D25BFC424.jpeg)

![Here we see Arnold Russell (right) and other members of 168 HT Squadron, probably taken in Gibraltar or Rabat Sale Morocco (he and 168 was stationed in both places) or perhaps Naples where he flew on occasion. This was probably taken in 1945. Wing Commander Fraser (CO at the end of the war) commented on Arnold's skill and dependability, saying: “... [Russell] has completed a very excellent job of setting up our overseas Detachment at Gibraltar and who also maintained 100% serviceability for almost 5 months overseas” . Writing home to his wife, Russell spoke about the challenges of the older Fortresses: “Just a note in a hurry again. Another a/c arrived last night, -----I am still busy on 9205 lots of trouble and expect to have it cured today if lucky. Had to go to Port Lagustey [sp] yesterday afternoon for spares, quite a trip by jeep, about 60 miles roundtrip. Nice country but old looking. We were back at 5 o’clock and no spares”. Photo: Russell family archive](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1626138608815-FKBVHI5ZKJGM6K879DYJ/DFFAAFE6-4540-41CB-A614-C6538F2A116E.jpeg)