AROUND THE WORLD, AROUND THE CORNER

The immensity and complexity of the Second World War seems beyond comprehension—a global and total war that reached every corner of the planet—from the remotest of Aleutian Islands to the estuary of the River Plate; from frozen Iceland to steamy Ceylon; from grey Murmansk to sun-baked Malta, from the broken streets of Stalingrad to the surrender of Singapore. The cataclysm involved hundreds of millions of people, vacuumed up the industrial might and natural resources of every country involved and some that weren't, brought about the brutal deaths of more than 70 million human beings, and changed the geography of the planet.

The known events and personal experiences of all involved seem more myriad than the stars in the known galaxies, a crawling blanket of deprivation, loneliness, mayhem, courage, evil, and politics. The best that one can do to understand any of it is to pull at one tiny thread, one fragile and incomplete filament, and follow its course as it weaves itself into the infinitely complex tapestry of the times.

For many years, we at Vintage Wings of Canada have been doing just that—telling the stories of Canadian fliers of the Second World War, one at a time—through written stories and flying aircraft. I personally have written several hundred of these stories for our website and have followed these threads as far as I could. Most disappear into the historical noise of the war and never emerge. Some do return to the edges of this tapestry of horrors, but at a place far from where they entered. Every participant was changed by the war, never the same again, for better or for worse.

When you've read enough Operations Record Books (ORBs), scoured enough combat reports, pondered enough photographs, and listened to enough veterans, strange things begin to happen. Stories begin to intersect, names begin to become familiar, events that seemed to happen at the ends of the world had tragic effects on the people who lived in your neighbourhood.

I recently researched and wrote a piece on my neighbourhood here in Ottawa, Canada, and its sacrifices in the Second World War. In my small and middle-class neighbourhood, far from the nearest battle of the war, I found the names of 472 servicemen who were killed or died of disease during the war and they represented every single major battle Canadians were involved in—The Battle of the Atlantic, the Battle of France, the Battle of Britain, Battle of Hong Kong, of Ortona, of Monte Cassino, of El Alamein, of Anzio, of the Scheldt Estuary, the Dieppe Raid, Dam Busters Raid, D-Day, Operation Market Garden, Battle for Caen, Battle of the Falaise Pocket, the Siege of Malta, the North African Campaign, the Conquest of Sicily, the Aleutian Campaign, Bomber Command, Fighter Command, Coastal Command, Transport Command, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Burma, Singapore, and more. Seen through the lens of my neighbourhood, I could begin to see the over and underlap of these tapestry threads, to recognize certain patterns, and observe the rise and fall of heartache over the five years of the war.

This week, yet another story intersected with my life—this one three times. Let me provide some background.

The Silver Spitfire

This week, Vintage Wings of Canada will play host to the Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team, the great Red Arrows, who will be performing at the Gatineau-Ottawa Executive Airport as part of their two-month long, 21-stop North American Tour. As great as the Red Arrows are, they will have to share the spotlight with the breathtakingly beautiful Silver Spitfire and its 27-country round-the-world expedition. The Silver Spitfire website explains their mission:

In 2019 two intrepid aviators will attempt to fly a Silver Spitfire around the world, taking in some of the most famous landmarks on the planet from the Grand Canyon in the West to the snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji in the East.

The Spitfire is a UK treasure and an emblem of freedom across the globe. The Silver Spitfire expedition will hopefully promote the ‘Best of British’ worldwide, showcasing the nation’s heritage in engineering excellence, and an aircraft that changed the course of history. The Spitfire embodies not only a pinnacle in aerospace engineering and design but commemorates a generation of intrepid aviators prepared to stand up to oppression and make the ultimate sacrifice in pursuit of freedom.

The expedition will reunite the Spitfire with the many countries that owe their freedom, at least in part, to this iconic aircraft. The unmistakable sight and sound of this aircraft once again gracing the skies aims to inspire future generations more than 80 years after R.J. Mitchell’s timeless design first graced the skies.

In the great tradition of exploration, we seek to challenge ourselves by setting out to complete a trip that has never been attempted. By pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in this iconic single-engined aircraft we hope to climb “a pilot’s Everest.”

The beautiful Silver Spitfire, sponsored by the luxury watch brand IWC. Photo by the John Dibbs, one of the world's top aviation photographers. Photo: John Dibbs

Another beautiful shot by John Dibbs. The Spitfire was stripped of all its paint in order to save the 300 lbs of paint it would normally carry—an idea that, combined with additional fuel tanks in the leading edge D-boxes, extended the range of the aircraft to 900 miles. Photo: John Dibbs

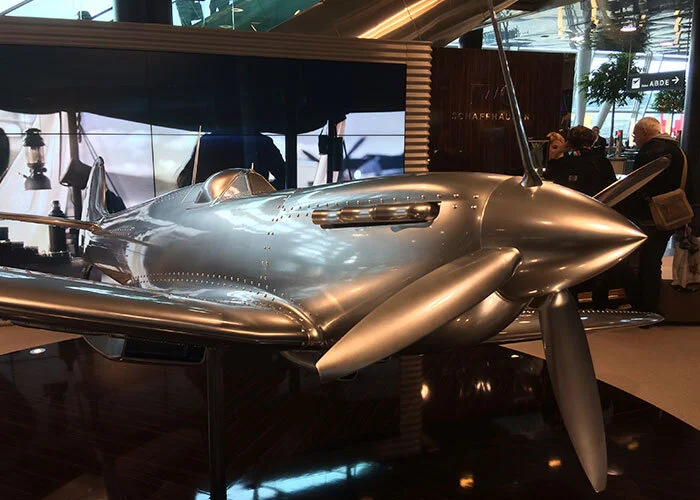

The sponsor, IWC Schaffhausen, was a natural connection since they have been using a Silver Spitfire in their marketing campaigns for some years—witness this shot of a 15-foot wingspan Spitfire model at the IWC Schaffhausen display at the Zurich, Switzerland, airport in 2016. Photo: Dave O'Malley

Related Stories

Click on image

On 10 May 1940, the German war machine unleashed their Blitzkrieg attack on France and the Low Countries that, within less than a month, resulted in the British Expeditionary Force being driven from continental Europe and the French capitulating. During this period, the squadron was locked in a bitter struggle with the Luftwaffe and though had accounted for more than 90 enemy aircraft shot down, had been decimated itself. Two pilots had been killed, six wounded and nine were missing in action. In the opening weeks of the month-long fight, much of which was covering a retreat to the sea, Weasel Woods-Scawen proved just how good he was, shooting down four Messerschmitt Bf 109s and a Henschel Hs 126. He also shared in the destruction of Dornier Do 17 and Junkers Ju 88. May 19th was particularly auspicious for Weasel, as on that day alone he shot down three confirmed Messerschmitt Bf 109s and a probable. However, he was also shot down himself, bailing out of his Hurricane and landing two miles from the Lille-Seclin aerodrome. During his descent, he was shot at by nervous French troops. The very next day, with the imminent threat of being overrun at Lille-Seclin, Weasel and other pilots of 85 Squadron were withdrawn by air transport to England for rest and re-equipping, followed two days later by the rest of the squadron. In that two-day period, they lost their brand new Commanding Officer, Squadron Leader Michael Fitzwilliam Peacock, DFC. He had been with the squadron for just two days. The squadron would not be ready to fight in the skies over the BEF’s withdrawal at Dunkirk, but Phillip’s brother Tony and 43 Squadron were there.

A typically fine photograph by the world-renowned John Dibbs reveals her British registration G-IRTY. Photo: John Dibbs

It was brought to my attention by my colleague Stephan King that part of the Silver Spitfire's combat history involved a two-week period in late November to early December of 1944 when she flew with 401 Squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force under the identity of her RAF serial number—MJ271. Known as “The Rams” for the Rocky Mountain sheep's head on its squadron badge, 401 (also known as the City of Westmount Squadron) has been a continuously active fighter squadron since its formation in 1937 as 1 Squadron (the 400-series squadron numbers came into use in March 1941). This unit is one of the most historic of RCAF squadrons and its battle honours include the Battle of Britain, Fortress Europe, Dieppe, Normandy, Arnhem, The Rhine, and much more. During the short period in 1944 when MJ271 joined 401, the squadron was heavily involved in dive-bombing and ground attacks throughout occupied Netherlands and Germany.

When she arrived at 401 in late November 1944, she was a bit of a beater, having been delivered to the RAF more than a year before. Since October 1943, she had flown operationally with 118 Squadron RAF on bomber escort duties followed by more escort sorties and dive bombing with 132 Squadron. She was seriously damaged in a wheels-up landing at RAF Ford in early May 1944. She arrived on squadron with 401 on November 23, 1944, after undergoing heavy repair and maintenance. MJ271 would go on to fly on 10 combat sorties with the squadron, flown by four different 401 pilots. The pilot who flew her the most (six times, including the first and the last) was Flight Lieutenant John Carson Lee who—and here's the FIRST intersection—grew up in my Ottawa neighbourhood known as the Glebe, at 195 Holmwood Avenue, just three blocks from my house! While he survived the war, he would die in the crash of a military aircraft... but I am getting ahead of myself.

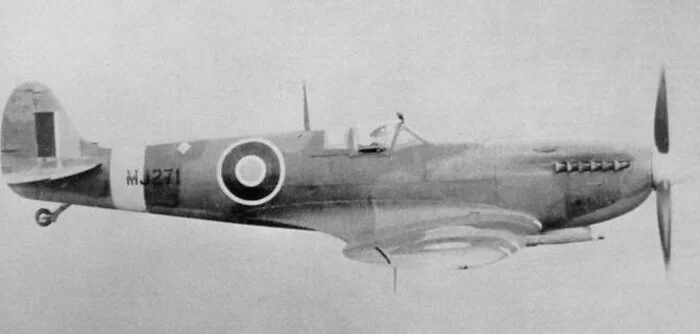

The only known photo of Supermarine Spitfire Mk IX MJ271. It is unknown when this photo was taken, but since there are no squadron markings and it looks freshly painted, it might be during a post-manufacture or post-maintenance test flight. This could have been taken either following its construction and delivery to 33 Maintenance Unit at RAF Lyneham where it was fitted with combat equipment and readied for frontline service, or perhaps after it emerged from the repair hangars following its wheels-up landing at RAF Ford while flying with 132 Squadron. Sadly, the 132 Squadron ORBs were not as detailed as those of 401. The squadron adjutant responsible for keeping the ORBs and records of events did not record any aircraft serials and in the events summary made no mention of the wheels-up landing, making it difficult to determine who flew MJ271 the day it was so seriously damaged. It is curious to see the pilot wearing his officer's cap rather than a helmet. This leads me to believe that this photo was taken during the delivery flight from the Supermarine factory at Castle Bromwich to 33 Maintenance Unit for installation of radios and guns. There would be no need for a helmet with radio headphones as there was no radio. The hat badge seems larger and brighter than a typical RAF pilot would have, and matches more that worn by most Air Transport Auxiliary pilots.

401 Squadron Service

The Silver Spitfire (then MJ271) first appears in the 401 ORB on November 28, 1944, at forward operating base known as B-80 near the city of Volkel in the Netherlands. Volkel, a former Luftwaffe fighter base, lay just 20 kilometres from the German border, and had been heavily bombed by the Allies before the arrival of the 2nd Tactical Air Force’s (2TAF) 126 Wing, comprised of 401, 411, and 412 Squadrons of the Royal Canadian Air Force. From Volkel, the entire wing was engaged in dive-bombing operations against German transport and military targets. My friend, the late Bill McRae, was a Spitfire pilot with 401 Squadron during D-Day and the push through France and Belgium. He was back in Ottawa and preparing for another duty in northern Canada by the time the wing had made it as far as B-80, but in a story published on this website, he explained the difficulties the wing had in operating one of the world’s finest air superiority fighter aircraft as a dive bomber.

The first 401 Squadron pilot to fly her was Flight Lieutenant John Carson Lee and he was “wheels in the wells” at 0840 that morning with five other “Rams.” The weather was clear all morning, but worsened by afternoon. They were briefed to bomb a “flyover” near Dusseldorf, Germany. A flyover is a junction of multiple rail lines in which one or more cross the others via an elevated track—obviously a very important target. However, they found an even “more important” junction south of the briefed target, and elected to attack it instead and “scored a very probable cut,” by which I believe they meant that the railway line was cut. Lee was back on the ground by 0930 with the last of his group landing 15 minutes later.

There are no known photos of MJ271 in service with 401 Squadron, but she would have been painted like this Spitfire—with the squadron's “YO” code. The 401 Squadron ORBs recorded the RAF serials (MJ271) and pilot's name for each sortie, which was extremely helpful in tracing the Canadian combat record of the Silver Spitfire. Unfortunately, there is no record of which aircraft code she was painted with (“Y” in the case of the above Spitfire).

The following day, the weather was “dull” and the Squadron did not get going until after 1100 hrs due to ground fog when six “Rams” launched the first of the day’s 32 dive-bombing sorties. Flight Lieutenant Harry Furniss of Montréal, Quebec, was in MJ271’s cockpit that morning and was airborne by 1150, bound for a railway junction northeast of the city of Coesfeld in the German state of North Rhine/Westphalia. Overhead the target, the Spitfires could not bomb as the railway junction was obscured by low cloud. Instead, Furniss and the other pilots of his flight of six Spitfires dropped their bombs on a rail line west of Coesfeld and scored two visible cuts in the line. Furniss and his mates were back on the ground at Volkel by 1300 hrs.

One of the four 401 Squadron pilots who got to fly MJ271, the first was Flight Lieutenant Harry Furniss of Montréal, seen here in civilian flight training before the war. Photo via Comox Air Force Museum

An hour and a half later, MJ271 had been refuelled and rearmed with two more 500-lb bombs. This time, John Lee was back in her cockpit and in the air with five others at 1435, vectored to a “priority flyover” south of Coesfeld. All six dropped bombs on the target area, but no claims were made.

The following day, 30 November, John Carson Lee had MJ271 again. The weather closed in and the first six 401 Squadron Rams, including Lee, did not get airborne until 1120. It was the only dive-bombing operation of the day and they were headed back to Coesfeld—a rail junction three miles northeast of town. The target was again obscured by cloud, so the flight headed to the city of Wesel, an important strategic depot for Germany and a frequent target. Because the city was protected by 75 barrage balloons at 500 feet altitude and obscured with cloud, results of their bombing could not be seen. The Spits were back on the ground safely at 1205 hrs.

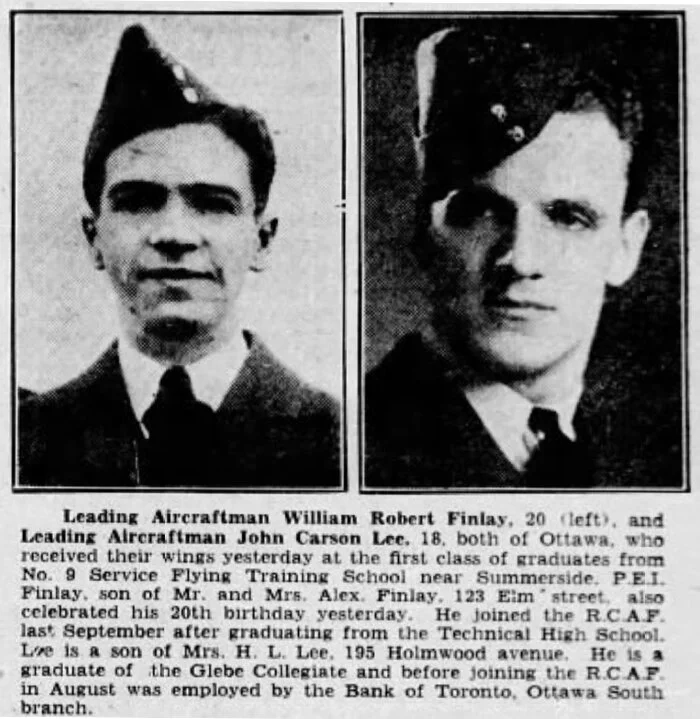

A newspaper clipping from the Ottawa Journal on April 17, 1941, announces the graduation of two Ottawa boys from Service Flying Training. John Carson Lee, who would go on to fly MJ271 on six combat sorties, grew up just three blocks from my home in the Glebe and survived the war. Sadly, William Finlay did not. He would not even make it to the end of the year as he was killed just five months later. He was “lost on operations at sea,” so it's possible he was with Coastal Command. Image via Newspapers.com

Due to continuing bad weather and icing problems, 401 Squadron stood down and MJ271 waited until 4 December before flying again—again with John Lee at the controls. It was dive-bombing again for Lee and the Rams and they were airborne at 1115 hrs, heading for an attack on a “priority” rail line between the cities of Wesel and Venlo. Bombs were dropped on the target, but no claims were made by the returning pilots. They recovered at Volkel at 1230 hrs that day.

A 126 Wing Spitfire IX from 412 Squadron taxies at B-80, near Volkel, Netherlands, in October of 1944 on a dive-bombing sortie over German rail yards with two 250-lb bombs slung underwing and a 500-pounder on the centreline. MJ271 was armed with two 500 lb. bombs (one under each wing) on all of her 10 combat sorties with 401 Squadron. Without dive brakes, the Spitfire was not a great dive-bomber and the wings could easily be overstressed. Photo: RCAF

On December 6, the wing moved 10 kilometres northwest to a newly completed forward airfield known as B-88, near the town of Heesch, Netherlands. It seems the squadron was grateful to arrive here after living for weeks in the bombed-out ruins of Volkel’s former Luftwaffe base. The summary of events in the ORB for 6 December makes it clear as to how they felt: “Aircraft took off during the afternoon and landed at the new Strip without mishap. Conditions were better than many expected—a real roof and a proper floor underfoot perked everyone up considerably…”

MJ271 was not in the air again until 8 December, the first day of operation flying from Heesch, this time with Warrant Officer M. Thomas. Thomas was a pilot who had a V-1 flying bomb kill and a jet kill to his credit (Arado 234), taking off from the steel Marston Mat runway at 1120 in the third section of squadron Spits to sortie. They attacked and cut a rail line northwest of the town of Hengelo in the east of the Netherlands still occupied by German troops. Hengelo, a major rail junction, had suffered much in the past few months. Two months previously, the historic centre of the city was accidentally bombed and destroyed by Allied aircraft with several hundred people killed. Thomas was back safely at Heesch an hour and five minutes after taking off. It would be a busy day for the Silver Spitfire.

Later that afternoon, John Lee was back in MJ271 and taking off at 1325 in clearing weather for a dive-bombing attack on a rail marshalling yard in the Westphalian town of Rheine. Rheine was a transportation hub with rail lines converging and the Dortmund-Ems Canal running though the city. Two clear cuts were made in rail lines and one locomotive was reported damaged. During their attack Lee and his section were attacked by three Messerschmitt 262 jet fighters. They made one bounce on the Spitfires and “showed no more fight and soon disappeared into the cloud.”

Lee and the rest were home by 1440 hrs. An hour later, MJ271 was airborne for the third time that day, with Warrant Officer Thomas back in the saddle. They made a dive-bombing attack on an unidentified rail line through clouds with no results observed. Thomas and MJ271 were home by 1640 when operations ceased for the day. (Later in the campaign, Thomas would be shot down, bailing out, evading capture and returning to his unit.)

The next day, the squadron stood down due to inclement winter weather. Pilots of 401 found stuff to do. Two made short post-maintenance aircraft tests; one group “invaded the little town of Oss for baths;” another went to the larger Dutch city of s’Hertogenbosch to purchase furniture for their dispersal, while another began painting the pilots’ room in the Dispersal Hut.

On 10 December, the squadron was late getting off due to weather, but Warrant Officer D. W. Davis was airborne in MJ271 by 1410 in the second section of 401 Spitfires to sortie that day. Davis’ target was a rail line near Heneglo, and after bombing and cutting the line, the 401 Spitfires were bounced by two “gaggles of Huns”—four Messerschmitt Me. 109s (Allied pilots usually called them Me-109s rather than the correct BF.109s), and then later eight Focke Wulf FW.190s. All returned safely by 1505 hrs.

The weather curtailed 401 Squadron sorties on 12 December with only six Spits getting airborne. The same was in store on the following day, only six Spitfires getting aloft that day and John Carson Lee was among them in MJ271. They lifted off the Marston Mats at 0930 hrs on a “dive-bombing show” but cloud obscured much of the land below. They ended up dropping them through cloud “somewhere in the area” of Coesfeld/Münster. They were home 50 minutes after launching, but the aborted operation was to be MJ271’s final sortie with 401 Squadron. It is not known what happened during Lee’s dive-bombing run, but the aircraft was deemed “over-stressed” and sent to an RCAF salvage and repair depot. Perhaps it was the cumulative stresses of pulling out from a dive during the 10 sorties with 401 Squadron, or maybe the result of one last aggressive pull by John Lee, but MJ271 would not return to 401 Squadron.

John Carson “Jake” Lee (J.5228)

After a brief search of the Internet, here's what I can tell you about the very interesting life of John Carson Lee.

He was born June 25, 1923 in the small town of Shelburne, Ontario, 40 kilometres south of Collingwood, the son of Harold Logan Lee and Florence Jessie Carson. His father worked for a bank in Shelburne. He had two sisters: Vivian and Frances (with Frances, he was one two surviving triplets), and an older brother named Harold. After Harold Lee Sr.'s time in Shelburne, he moved his family to Winchester, Ontario (60 miles south of Ottawa), where he became manager of the local branch of the Royal Bank of Canada. Here, in 1931 in his basement, he would shoot himself through the heart with a 32-calibre revolver over serious personal financial problems. His wife Jessie discovered the body. He left three letters of explanation—one to his wife, one to the coroner, and one to the undertaker.

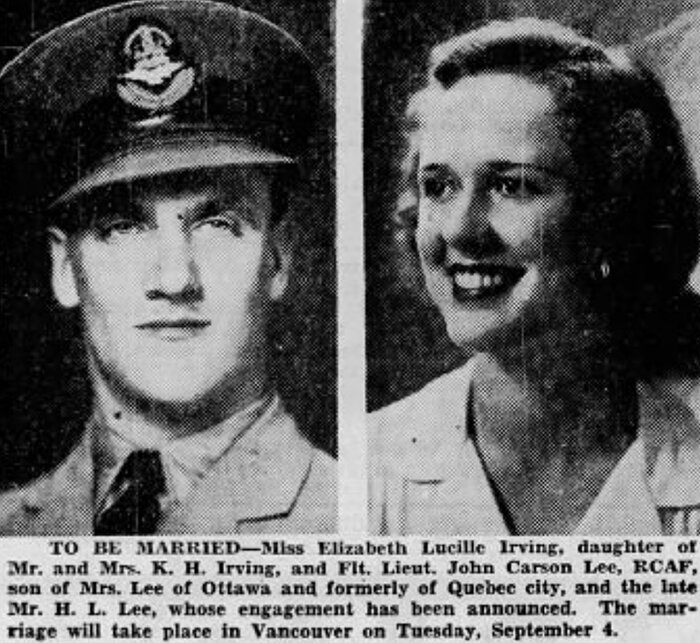

Following this horrible family tragedy, Jessie took the family back to Quebec City where her and Harold's family were from. Later the family would move again—this time to Ottawa, taking up residence at 195 Holmwood Avenue in Ottawa's middle-class Glebe neighbourhood. Young John Lee attended Hopewell Avenue Public School and Glebe Collegiate Institute, where he was an outstanding athlete. It was during his time at Glebe Collegiate that Lee met and fell in love with the spectacularly beautiful Elizabeth Lucille “Betty” Lee, who also lived on Holmwood Avenue. He was 16 and she was 15. Betty's earliest memories of their time together were afternoons swimming at Brighton Beach along the Rideau River, where Lee taught her to do the Australian crawl swimming stroke. Lee could make Betty laugh at the drop of a hat, and often showed off by diving off the top of the diving platform. She remembers the particular afternoon when they first fell in love—sitting at the top of that diving platform, talking about anything from the food they liked to music and their future plans. Even at this early time, the aviation-dreaming Lee would have talked about his plans to learn to fly.

Following high school, he was briefly employed as a ledger keeper at the Toronto Dominion Bank in Ottawa South, a neighbourhood just south of the Glebe. Impatient to answer the call, he joined the RCAF at Ottawa in August, 1940, on his 18th birthday. He traveled by train to Toronto to begin his training at No. 1 Manning Depot. After his Initial Training, he completed his ab initio training on Fleet Finches at No. 11 Elementary Flying Training School at Cap-de-la-Madeleine near Trois-Rivières, Quebec. He earned his pilot's wings on North American Harvards at No. 9 Service Flying Training School in Summerside, Prince Edward Island, and was part of that school's first graduating class. His wings were pinned on him by Colonel The Honourable James Layton Ralston, the Minister of Defence who called Lee's class “No. 9's first installment of bad news for Hitler.” Ralston also added: “The fact that you are here, that you have won these wings, is a guarantee that you will bring honor [sic] to yourselves and honor to the country you come from.”

Following his graduation from No. 9 SFTS in April 1941, he was commissioned as a Pilot Officer and selected to become a flying instructor, likely a disappointment for a keen young pilot inspired by the exploits of Canadian pilots in the Battle of Britain. He was sent to No.1 Flying Instructor School at Trenton, Ontario, located north of Lake Ontario on the Bay of Quinte, at the midpoint between Toronto and Ottawa. After qualifying as a flying instructor, he was next sent to instruct student pilots not a whole lot less experienced than himself—at No. 2 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Uplands in Ottawa, one of the largest single engine training schools in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Although he likely was hoping for a transfer to a combat role, he was just a few miles from his home and could visit Jessie, high school chums, and his sweetheart Betty anytime he wanted. There is a family memory that Lee's mother, Jessie, who had contacts in the Department of National Defence, pulled some strings to get him the instructor's job in his home town.

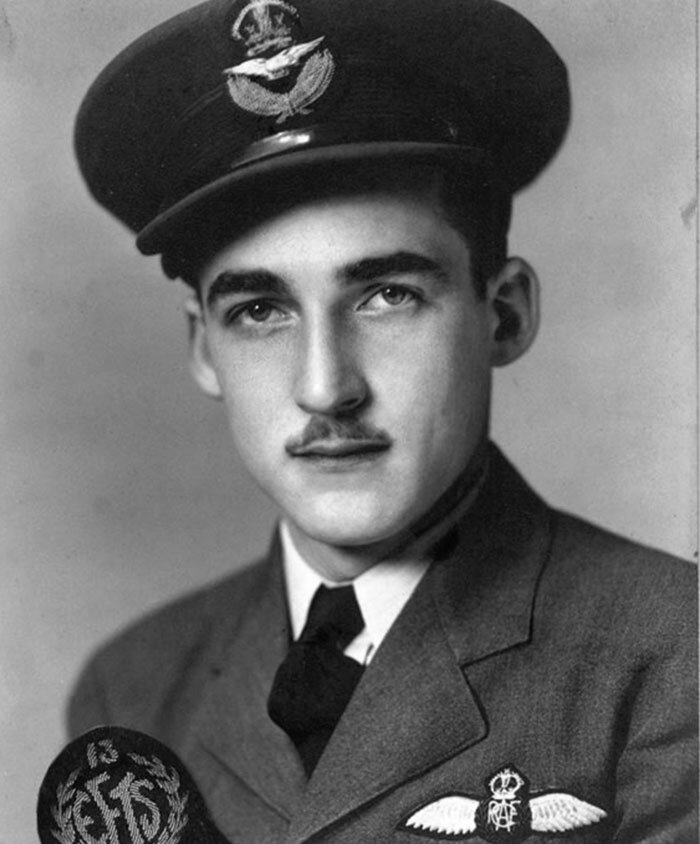

So... here's the SECOND and even stranger intersection. My former father-in-law, Wing Commander Frederick C. “Fred” Jones, followed a similar arc in the RCAF—instructor then Spitfire pilot. During Fred's training at RCAF Station Uplands, one of his instrument flight instructors in 1941 was none other than Pilot Officer John Carson Lee! According to Jones’ logbook, his totals for the months of January, April, and July 1942 were signed off by J. C. Lee P/O, Commanding “A” Flight No. 1 Squadron.

After attending Flight Instructor School at Trenton, John Carson Lee became a flying instructor at No. 2 SFTS Uplands. There, in his first summer instructing, he taught my former father-in-law, Wing Commander Frederick C. “Fred” Jones (above) how to fly Harvards. Photo: Jones Family

Flying instruction duty was tedious, but Lee did his duty at Uplands for almost three years before earning the chance to fly fighters in the European Theatre of Operations. Before he left for operational training on the Spitfire, Lee proposed to Betty. They agreed that they would wait until his return to be married as he did not want to leave her a widow should he not make it back. She accepted his proposal and when he left for the war, Betty moved out west where her brother, Dr. Jack A. Irving, had moved. She stayed with Jack and his wife, the former Margaret “Peggy” Sheridan, at their home in Vancouver until John's return.

Here's where the third intersection with my life occurs. My wife Susan's beloved Uncle Jack Sheridan (a former RCMP officer and a hero of mine who lived to be 101 years old) was the brother of Peggy (Sheridan) Irving who was—a surprise to me—John Lee's sister-in-law. Serendipity doesn't come in much bigger doses!

Lee was not a prolific letter writer. In all the time the young Flight Lieutenant was overseas (possibly around 18 to 20 months) he wrote to her just 22 times, according to Betty. His letters were always about their love and their future and never about operational flying. You can hear the fondness and understanding in her voice when she speaks about his letters 75 years later.

Eventually Lee made his way to 401 Squadron on 2 July, 1944. He first appears in the squadron ORB when he is posted in from No. 83 Group Support Unit (GSU) at RAF Bognor. 83 GSU was a holding unit for aircraft and pilots for operational squadrons in 2nd Tactical Air Force. They maintained a large number of aircraft of all types used by the squadrons in each group, prepared ready for issue to the squadrons to replace losses. It is possible that Lee did his conversion here as well.

Lee, whom his squadron mates called “Jake,” was in the thick of it just a couple of days after his arrival. His first operational sortie was escorting Typhoons on a mission to bomb a rail yard. Over the next month he flew regularly with his new squadron mates and several times with the late Flight Lieutenant Bill McRae, a dear friend of Vintage Wings of Canada and myself. During his time with 401 Squadron, Lee was tasked with taking care of the squadron dog Spitfire, which Lee called “Spittie.” Bill would leave the squadron on August 12, 1944, but Lee remained well into 1945. By the time he was demobilized, his final tally was two enemy aircraft shot down and one probable. His last aerial victory was on New Year's Day, 1945. His after action report states:

“I was flying Yellow 1 on a sweep of the MUNSTER/RHEINE area. Just EAST of MUNSTER Red 1 ordered my section down on two engines [locomotives-Ed.] coming out RHEINE. As I dived to attack, I saw an Me. 262 right below me and gave chase. The jet job led our section into about a dozen Me. 109's and F.W. 190's [sic] doing a circuit of the drome. I attacked one of the 109's and fired several bursts from 600 - 300 yds. varying deflection from 60º to 10º — I saw strikes on the cockpit and wings and the aircraft rolled over and went straight in.

I claim 1 Me. 109 DESTROYED

SECOND COMBAT

I then attacked at about 5,000 ft another Me.109 and fired the rest of my ammunition from 700-400 yds with deflection 30º to 10º and saw strikes all along the port side of the fuselage. He flipped to port and then dived away to the starboard in a fairly steep spiral pouring black smoke quite badly. I last saw him still pouring lots of smoke at 2,000 ft.”

I claim 1 Me. 109 PROBABLY DESTROYED

It was clear from the pages of the 401 Squadron ORBs that Lee was now a highly experienced combat pilot with scores of combat sorties under his belt. On April 11, 1945, his name appears in the Squadron ORB for the last time—an armed recce sortie. Another pilot, P/O Gillis, was having mechanical trouble and Lee was ordered to escort him back to Heesch. His name never appears in the 401 ORB again... not even in the POSTINGS OUT summary section of the ORB for April.

In August of 1945, he was 23 years old, still in uniform and engaged to Elizabeth Lucille Irving of Vancouver, having just returned from overseas, likely stopping in Ottawa en route to visit his mother and family. They were married in Vancouver a couple of weeks later on September 4, 1945, with his mother Jessie making the journey by train from Ottawa to attend. The couple honeymooned at Lake Louise, then took up residence in Vancouver.

John and Betty's engagement notice in the Ottawa Citizen, August 29, 1945.

Mr. and Mrs John Carson Lee on the day of their wedding. John had been demobilized after his return to Canada but was still in uniform for their wedding day. Elizabeth, known as Betty to her friends, and John were both 23 years old. According to the Vancouver Sun's society pages, Betty wore a “Queen's blue crepe afternoon-length frock and chapel veil of matching blue held by a floral halo in matching tones,” while her bridesmaid, Miss Nora Moody, wore a “maize crepe tunic model.” Wing Commander F. K. Belton, RCAF chaplain, presided over the marriage. Lee's best man was none other than RCAF Spitfire pilot and double ace Squadron Leader Don “Chunky” Gordon, DFC and Bar, DFC (American), who shot down 12 enemy aircraft in the war. Lee would have known Gordon from their time at 83 Support Group Unit or possibly they met when Gordon was with 442 Squadron, 144 Wing in the same area of the Netherlands. According to Betty, now 97, Lee ran into Gordon in the streets of downtown Vancouver the week before they were to be wed and asked him to stand as his best man. Always up for an adventure with an old flying pal, Chunky happily agreed. Lee's formal RCAF portrait (in engagement notice above) shows a man of steely eye and square jaw, but here we see him as the man Betty married—an often funny and happy spirit who is clearly delighted with his new situation. Photo via Brian Irwin

A great shot of "Chunky" Gordon in the cockpit of a 274 Squadron Hawker Hurricane in North Africa. Photo via acesofww2.com

John and Betty lived in Vancouver for two and a half years following their marriage, and Lee took jobs wherever he could while he sought out employment as a pilot. He'd wanted to fly since he was a teenager, and the few thousand hours he amassed as an RCAF instructor and fighter pilot did not quench his thirst for flying. While working at an import/export business in Vancouver, Lee applied to commercial transport operators including Trans Canada Airlines (now Air Canada), but the airlines turned him down, citing a preference for pilots with multi-engine experience. While flying fighters on a frontline squadron was the apex of anyone's flying career, it put him at the back of the queue when it came to flying airliners.

John was getting desperate and was convinced that the United States could offer up more opportunities for an enthusiastic and experienced pilot... even if he was a Spitfire pilot. So he made plans to move to Long Beach, California, where he hoped flying would be in his future. Betty dutifully followed, now five months pregnant. In those days, all you needed were two sponsors to move to the USA and start working. They arrived in December 1947 and in April 1948, their son David was born. Lee still pursued his dream of professional commercial flying but worked all sorts of odd jobs, including in the many southern California oil fields.

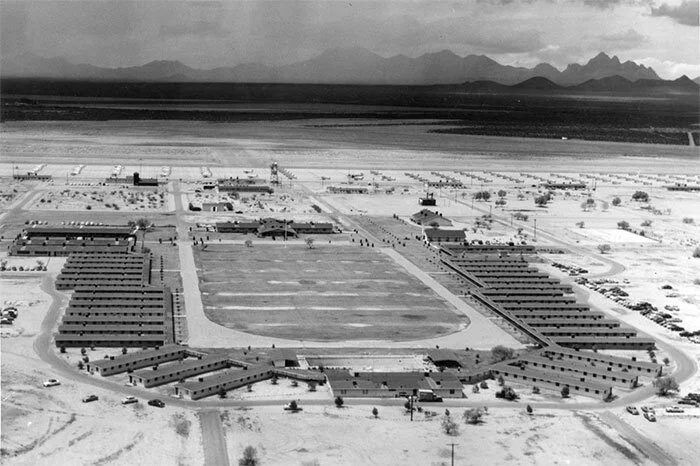

Finally, in 1951, Lee caught a break and was hired by the Darr Aeronautical Technical Company, a private contractor that had been tasked with setting up and operating an air force flying training facility at the mothballed Marana Air Force Base northwest of Tucson, Arizona. The large base had been closed for a number of years after the war, but was reopening to provide basic flying training to American ROTC and USAF cadets and foreign air force students from countries such as China, France, and Turkey. John and Betty, with son David in tow, moved to Tucson and took up residence in a duplex. John was a civilian flying instructor on the T-6 Texan trainer, something that he was very experienced with since it was what he taught on at Uplands (the Harvard in RCAF parlance). Later, he would go on to train pilots on the North American T-28 Trojan and possibly on the T-34 Mentor.

A great photo of Marana Air Force Base in 1956 during its heyday showing the barracks complex and parade ground and the flightline in the distance. Operated by Darr Aeronautical Technical Company from 1951 to 1957, the base was closed by President Eisenhower along with 29 others. It was a shame to close this particular base since, according to former USAF pilot Dale Elliott who trained in the area, there was not one flight cancelled due to inclement weather during its years of operation. Photo via tucson.com

A train car–load of flight training cadets from Norway, Belgium, and France arrives in Tucson in 1951 and are greeted by officers from Marana. Photo via tucson.com

The T-6 Texan flightline at Marana where John Lee spent his days training younger pilots. It was Lee's long-term hope to get into the lucrative airline flying business. Photo via tucson.com

The Beech T-34 Mentor, along with the North American T-28 Trojan, was a replacement trainer for the T-6 Texan of Second World War vintage, which was being phased out of USAF use in the last half of the 1950s. Betty remembers that John Lee conducted flying training on more than one different type, so it is likely that he was also current at the time on one or both of these two more advanced training aircraft. Photo via tucson.com

The Douglas DC-6 in National Airlines livery flies for a glamour shot over the hotel-lined West Palm Beach, Florida, around 1953. The DC-6 and its bigger sister, DC-7, flew with National well into the 1960s. Photo via EdCoatesCollection.com

John began contract flying during these furloughs. One time, he signed on with a commercial operation flying supplies to one of the sides in the Congo Crisis, a series of civil wars immediately following independence from Belgium between 1960 and ’65. This period of upheaval, that cost the lives of an estimated 100,000 people, was a proxy-conflict in the Cold War in which the Soviet Union and the United States supported opposing factions. It is not known if this “commercial” operation was some front for the CIA or other US agency, but John was gone to Africa for three months and would not talk about who he was flying for after his return.

Betty and John had a deep love for each other, and though their economic lives were still on unsteady ground, he always made her laugh. One of John Lee's character traits Betty remembers best was that sense of humour—not the back-slapping “hail fellow well met” type of jocularity, but rather a quick-witted dry humour and a disarming yet charming take on the world. She remembers his return from Africa well—loaded down with ivory crafts from Congo, he had her doubled over laughing before he could even get through the door.

By 1962, Lee had been flying for National on and off for nearly five years, and he and Betty felt that they were on the verge of steady employment and much better pay. During another furlough later that year, John took up flying for an air cargo company called Air Carrier Leasing Corp, also based in Miami. On December 13, 1962, he was co-pilot of a cargo-converted Flying Fortress (registered N131P) working its way to Panama City, Panama, from San Juan, Puerto Rico, where they had delivered a load of beef. It appears that Lee, who was now 40 years old, and his aircraft commander William F. Patterson (30), were well south of the direct route from San Juan to Panama City when they crashed in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains of Colombia, about 40 miles southeast of the northern coastal city of Santa Marta. They impacted the snow-covered mountainside at 11,500 feet.

A photo of Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress N131P (USAAF serial 44-83439) during its short time (October 1959 to late 1962) with Paramount Aquariums Inc. of Vero Beach, Florida. Paramount acquired the Fortress and had it converted in Tucson, Arizona, to carry tropical fish. It carries what looks to be a graphic of a Siamese Fighting fish on its tail and the title PARAMOUNT AQUARIUMS aft of the cockpit. The aircraft was white over a pale blue underside and the tail gunner's position was fared over. The white over light blue with a red cheatline was a paint scheme used at one time in the civilian aerial spray/fire-fighting role. This photo was shot at Oakland, California. Photo via Milo Peltzer Collection

Betty, who remembered getting up in the middle of the night to say goodbye to her husband before he left on this particular flight, now knew that he was overdue, waiting to get word. She hoped perhaps the pilots were bobbing in a life raft somewhere on the Caribbean. Unfortunately, her hopes were dashed when she learned of the crash on television.

Both the FBI and the CIA had been searching for the Fortress since December, when the crash site was reportedly discovered by a local native on March 19, 1963. According to an article in the Chicago Tribune on March 25, 1963, a recovery team was able to identify the bodies of both Patterson and Lee based on documents found in the wreckage—but, as the Tribune reported, they also found a third unidentified body. Patterson was the son of a prominent Chicago lawyer and the article went on to quote Patterson's father as saying “The plane might have been hijacked. There were supposed to have been only two men, my son and his co-pilot in the plane when it took off for Panama.” While the grieving father hinted at hijacking, there is no proof such a thing ever happened. I cannot find record of the identity of the third man or any proof that the story of the discovered documents and bodies in the Tribune article is 100% factual. Most sources indicate there were only two fatalities. For certain, there is still controversy as to when the wreck was discovered and by whom.

High in the arid alpine heights of Colombia's Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains, near the shores of tiny Lake Uldumindia, lie the last remains of John Carson Lee. The remote and sacred spot connects with Holmwood Avenue in the Glebe and to the Silver Spitfire's journey to 27 countries around the world. Photo: https://www.gobernacionkogui.org

Elizabeth Lee and their son David must have held out hope for months that Jake would still somehow be found alive. Sadly, due to the extreme difficulty getting to the wreck site, it would become his permanent gravesite. In the great aviation forum Warbird Information Exchange, a post from a man named Wyman Culbreth, who had visited the site in summer of 2014, stated “There are stories from the Kogui Indians as well but not firsthand, that two Indians spotted the wreckage from a trail above on route to another village. After some time it was reported to police, and religious leaders then came up from the village of Don Diego and held ceremonies for 8 days. Lake Uldumindia is one of two of the most important lakes in their lands, and they now consider the wreckage part of the spirit of the lake.”

Betty and her family have a more likely scenario about the discovery of the wreck site. The site was indeed first discovered by Kogui Indians, who went down to speak to a missionary by the name of Ross Clemenger who, as part of an non-governmental organization, was helping local farmers to cultivate coffee beans. They guided him to the crash site and he was able to ascertain the identities of the casualties and bring the news and some artifacts out. Betty would meet Ross Clemenger, who lived on Vancouver Island, many years later, and he told her the story. Clemenger, who worked tirelessly to help and support people in Columbia through NGOs and micro-financing, died in 2012 at age 88.

Though John had died in an airplane crash, he was on furlough and working for another operator, so there was no compensation or benefit coming from National Airlines. However, National would help Betty with employment in the company's accounting department, where she would work for three and a half years following John's death. Though alone now, Betty did not want to move from Miami until her son David had graduated from high school. She recalled, after the death of his father, that David demonstrated great emotional strength and support for his mother, telling his Betty: “We'll get by.”

John Carson Lee's last resting place is so remote that only a few visitors have ever been there—mostly native Kogui people who have embraced Lee's memory as their own. Certainly, given its extremely remote location, none of his family has ever made the difficult trek to pay their respects. But Lake Uldumindia is connected in story to 195 Holmwood Avenue in Ottawa and to all 27 countries that the Silver Spitfire will visit in the coming months. Though IWC Schaffhausen's logo is emblazoned on the outside, John Carson Lee's spirit runs through MJ271 along with those of fellow Canadians Furniss, Davis, and Thomas of 401 Squadron, as well as those pilots of 132 and 118 Squadrons and the Royal Netherlands Air Force (MJ271 was transferred to the RNAF after the war) who brought her safely home time after time while she was an operational Spitfire. No doubt the pilots of the Silver Spitfire, Matt Jones and Steve Brooks, will do the same.

Jessie died in 1969 after a long illness and a life marred by tragedy. Betty would eventually remarry and continue to live in the United States for many years. Recently, she moved back to Canada, taking up residence on Vancouver Island to be near her son David—“The light of my life.” At 98 years old, she is as charming and beautiful as that 15-year-old girl at Brighton Park Beach and has an extraordinary memory for things that happened more than 80 years ago. I am glad that I pulled at this one particular thread in the tapestry of the war, for it was woven with other familiar threads and led in a long meandering and beautiful weft to Betty, the love of John Carson Lee's short but adventurous life.

For John and Betty

Dave O'Malley