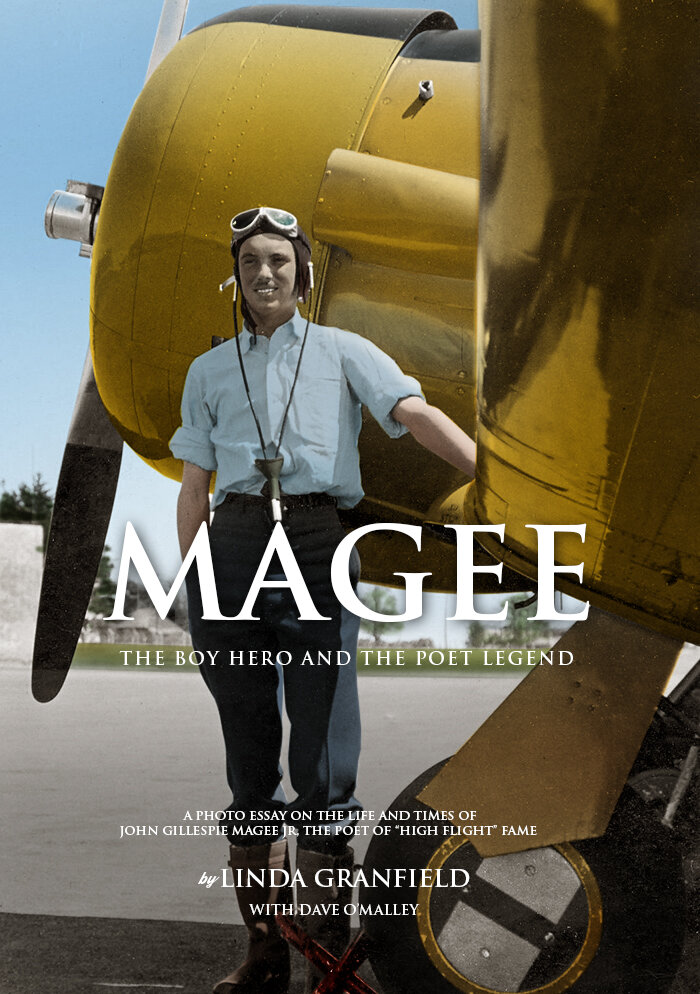

MAGEE — The Boy Hero and the Poet Legend

On 18 August 2016 it will be 75 years to the day since a teenager named Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Jr. lifted his Supermarine Spitfire Mk I from the aerodrome at RAF Llandow in Wales and climbed “sunward” up into the “long, delirious, burning blue.” He had a tank full of petrol and a heart full of expectant joy. The result of the next two hours was the loss of several hundred gallons of His Majesty’s 100 octane fuel and the visceral inspiration for the literary world’s finest expression of the exhilaration and spirituality of flight—the poem we all know as High Flight.

By the time young Magee had unstrapped, dismounted and debriefed, he had penned in his mind major sections of his iconic poem. He died a few months later during his eightieth flight in a Spitfire. He did not live to see the jet age, universal airline travel, or men walking on the moon. He did not live to see his words etched in stone on every continent or hear his words uttered by presidents and astronauts, and flyers of every stripe. He did not live to experience the solace his words would bring to bereft families or the glory they painted for the fallen aviators of his own war. He did not live to see the powerful effect his words would have on his aviator brothers and sisters. He did, however, live just long enough to pluck 114 words from his heart and string them together to form a hauntingly perfect descriptive strand of aviator DNA. In these words and lines can be found the emotional and inspirational genetic code that reveals the aviator, that explains the passion we have for flight, that inspires us to climb sunward.

His were not the words of modern aviation, of GPS, avionics, air traffic control, and launch and leave. His are the words that describe human flight before utility. Of wings and clouds and three dimensions. Of flight before external controlling forces, technology and regulation chipped away at the joy. His words describe the aviator of the First World War, of barnstorming, of his own war and of today’s working aviators who still sense that fundamental rolling and scissoring strand of DNA deep in their bodies—a strand that traces a hidden line from their exultant hearts to their poetic minds. A strand that reveals itself as a tingle rising up the connecting spine.

Though John Magee was flying Spitfires at the age of just eighteen, he was a particularly thoughtful young man, who, despite being deeply thrilled and moved by flight, saw his role in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as protector and avenging angel for his beloved England—an England in great national stress at the time of his arrival there as a fighter pilot. His contemplative soul and his strong sense of right and wrong were formed by his Christian upbringing, his loving and dedicated parents, his rich education and his international early life.

Magee’s beloved poem has, since his death and the rise in the popularity of his sonnet, led many to study his short life in an attempt to shed light on what, in his character and upbringing, gave him so much creative insight and deep spirituality at such a young age. On the anniversary of his creation and in honour of his incredible contribution to the Royal Canadian Air Force, Canada and the world of aviation, we present for you a visual essay of photographs from the Magee family albums and files of the RCAF. Chronicling his short and interesting life, his supremely accomplished parents and his path through training, many of these photographs have never before been published.

The photographs from the family albums have been shared with historian and writer Linda Granfield by two of Magee’s younger brothers, David (deceased) and Hugh. Linda has written much on Magee for young people and serious researchers alike and has, over nearly two decades, established a strong bond with the Magee family, based in trust and a shared desire to tell the true story of this remarkable young man. Her familiarity with young John Magee Jr.’s life and the following images only just begin to tell the story of his brief time on this earth, but give us powerful visual insights into a tumultuous period in time and a familial ethos of justice, duty, sacrifice, honour, courage and faith.

Let’s let Linda Granfield now tell the story.

Dave O’Malley

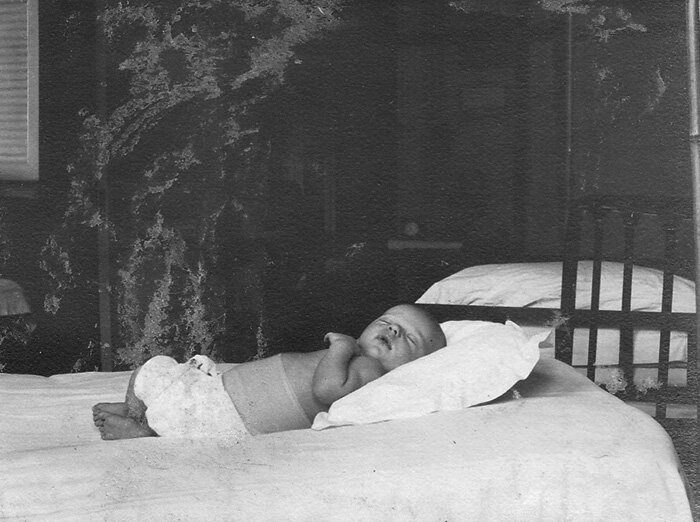

Introducing… John Gillespie Magee, Jr., born 9 June 1922 in Shanghai, China. He snoozes in the humid nursery, his umbilical area wrapped and his cloth diaper rather low-slung. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

John was the first-born child of the Reverend John Gillespie Magee (b. 1884) and Faith Backhouse Magee (b. 1891). Magee, from a prominent family in Pittsburgh, PA, went to China in 1912 as a missionary; likewise, Faith, a British-born missionary, had arrived in 1919. The two fell in love within weeks of meeting and were married in Kuling, China in July 1921. Through marriage, Faith became an American. The four Magee children, born in China, Japan, and England were American citizens by virtue of their father’s citizenship. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Related Stories

Click on image

The first-time parents filled a “baby book” with a record of John’s early days: photographs, lists of gifts received, and the names of family friends. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Faith has written “Baby’s Baptism Card in Chinese” at the bottom of this family document. John Jr. was christened in 1922 wearing a handmade gown stitched by his aunt Ruth Backhouse. The gown was shipped from England and arrived in time for the ceremony in China. While hundreds of Magee documents have been donated by the family to the Yale Divinity School Library, the gown remains in the hands of the family. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

John Magee’s early years were spent in Nanking (Nanjing), China, then the capital. The Magees lived in a compound built in the 1920s by the Reverend Magee in Hsiakwan (Xiaguan), a poor area outside the ancient walls of Nanking. The chapel, school for local Chinese children, and homes of the Magees and other staff, were near the Yangzte River. The Magee children watched the shipping on the Yangtze from the walkway on the roof of their home. This early photograph shows the school and chapel buildings in the 1920s; the chapel is now a school library named for the “first principal,” John G. Magee Sr. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

The Reverend John G. Magee is a hero in China for his work with the International Safety Zone Committee, a group of businessmen, doctors, and clergymen who saved over 200,000 Chinese civilians during “The Rape of Nanking” in 1937. While Magee and the others struggled to keep the invading army of Japan at bay, his children were safe in England with their mother. Photo: Linda Granfield

On a rainy day, father and son visited the Mausoleum of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the father of the Republic of China, established in 1911. Sun Yat-sen, whom John G. Magee met, died in 1925. His tomb was built between 1926 and 1929 atop Purple Mountain in Nanking (Mount Zijin, Nanjing). This photo was taken in 1928 or 1929. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

A passport issued to 11-year-old John Magee on 10 April 1934 describes him as 4’ 11” tall, brown hair and eyes. Place of birth: China. Student. A later page is stamped in New York, on 18 April 1934—John is in transit to England, “returning to St. Clair [Clare] School, Walmer, Kent.” John G. Magee, both father and son, have signed the passport photo. Photo: Linda Granfield

The entire Magee family poses for this photograph taken in February 1933 in Deal, Kent, England. From the left are David, John, and Christopher. Also “present” is Frederick Hugh who will be born that August. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

The Magees decided that their children’s early schooling would be in Britain and university studies would be in the United States. In this way, both parents’ heritage, traditions, and families would be part of the children’s lives. The first three children moved to England with Faith; John Sr. sailed from China during his furlough years. The fourth Magee son, Frederick Hugh, was born in London in 1933. John, the eldest, holds Hugh on his christening day (there’s the Magee gown again.) With him are brothers Christopher (1928–2005 born in Japan) left, and David (1925–2013 born in China) right. Hugh Magee is a retired clergyman living in Scotland. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

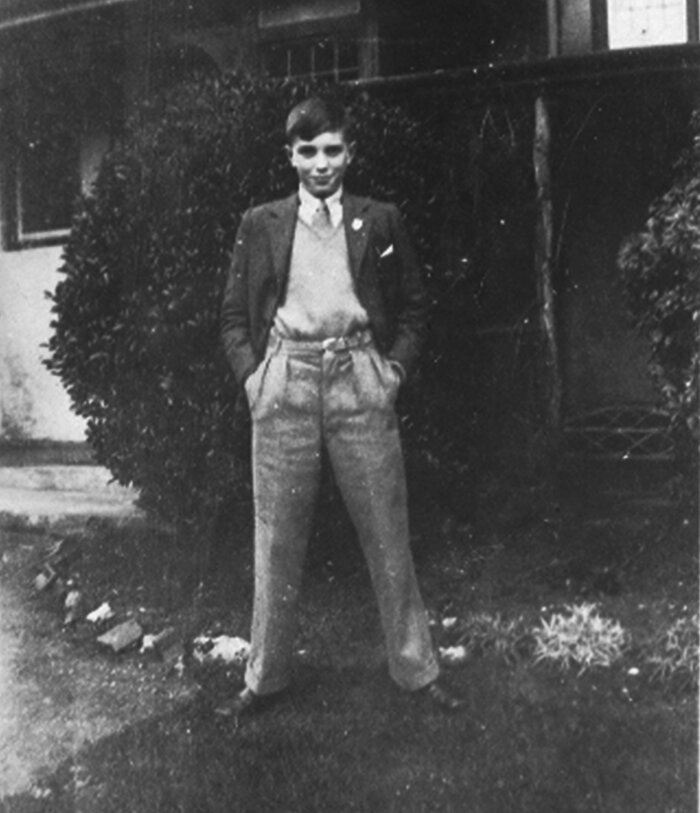

This photograph, believed to have been taken in 1937 at Tunbridge Wells, England, captures the boldly confident adolescent and cheeky trickster in one snapshot. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

One of the few coloured (hand-tinted) photographs of John. It was taken in the spring of 1938 when John visited family in Mortehoe, a village in Devon, England during lambing season. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

The jacket (from previous photo) reappears in the family photo taken that same year, during the Reverend Magee’s furlough spent with the family in England. Given the nature of Magee’s missionary work in China the family was rarely fully united during the 1930s. John revisited his grandmother in Mortehoe in 1941, just weeks before his death; during this visit, he wore a new uniform “which fits a great deal better than the old one!” he noted. (Left to right in bottom photo: John G. Magee Sr., Hugh, John, Christopher, David, Faith.) From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Cool shades! Sailing, in fact, anything to do with boats of any sort, was a favourite pastime. Here, John’s paddling at Rugby School in 1938. Trevor Hoy, John’s study partner, described him as a “genius daredevil.” While he excelled in Latin and Greek (“which dialect?” he’d cheekily ask) and wrote for the school literary magazine, he was also a prankster who climbed up the side of the school clock tower and took his punishment in “the Birching Tower.” Much to the teachers’ dismay, John would exit the tower smiling! At Rugby, John was also a member of the Officers Training Corps. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Before he left for his summer holidays in Pittsburgh, 16-year-old John welcomed his mother to Rugby School’s Speech Day, 1939. He was presented with the Rugby School Poetry Prize for his piece “Brave New World.” Rugby alumnus Rupert Brooke, the famed poet who was killed in the First World War, had won the prize in 1905; Brooke was idolized by John and he later wrote a Sonnet to Rupert Brooke. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

In the garden photograph, taken on Speech Day, Faith Magee is sitting on the bench; John is standing, facing her. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, John Magee was visiting his aunt, Mary Scaife, in Pittsburgh. He had sailed with a friend from England, and while in the United States they visited the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. However, when the summer’s end arrived and it was time to travel back to England for his graduation year at Rugby School, John could not leave the U.S. As an American citizen he could not be issued a visa; his English-born friend returned to Rugby alone. John’s last year of high school was spent at Avon Old Farms School in Connecticut. One can only imagine what it would be like to unexpectedly attend a new school, bereft of close friends, separated from his parents (father John was still in China; mother Faith was in England with his brothers), and having to quickly get in tune with different curriculum expectations. Nonetheless, John graduated in June 1940 and had been accepted at Yale University. He asked to postpone the beginning of his Yale studies so that he could join the war effort. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

While at Avon Old Farms School (1939–1940), John continued to write poetry. In fact, as part of a school assignment he produced a bound collection of his poems. He set the type and printed the pages on the school’s printing press. He also bound the volume in light blue paper. The book of poetry, of course, predates “High Flight” (1941) and so does not include that poem or “Per Ardua,” considered the last poem he wrote before his death. Approximately twenty copies of Poems by John Magee were printed by John; it is a rare volume. This yearbook photograph captures John as “the poet” in nature during his final high school year. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

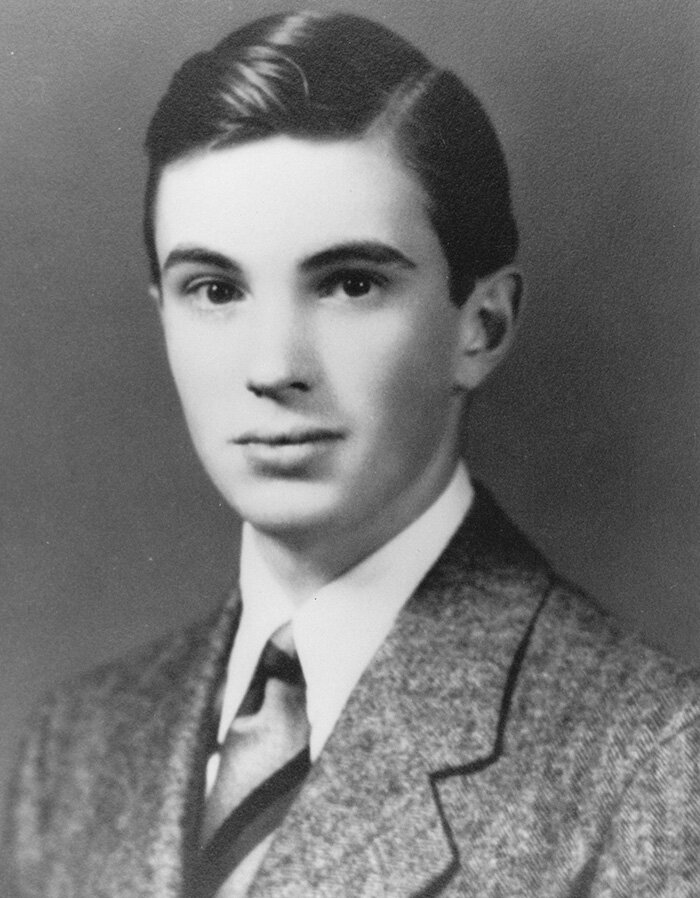

John mentioned to a newspaper reporter that in September 1939 he “had to get into it [the war.]” He said that he “was too young at 18 to qualify for the British Ambulance Corps [so] he packed up and left for Montréal. He was about to enlist in the Canadian army when he ran into some friends who persuaded him to join the air corps.” The New Paramount Portrait Studio in Toronto (still in operation) photographed many of the Royal Canadian Air Force recruits. In 1940, John Magee, sans moustache, sat for his first military portrait. Via Manning Depot No. 1 in Toronto, he’d soon be acquainted with the “Horse Palace Cough,” as he slept with hundreds of others in bunk beds set up in the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) grounds near Lake Ontario. The nearby boardwalk and dance halls provided diversions for John and his new air force friends. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Aircraftsman Second Class Magee. Photograph taken in late 1940 during John’s first weeks in the Royal Canadian Air Force spent on guard duty in Trenton, Ontario. Eighteen years old and flush with the excitement of being away from family, John spent time off socializing in nearby Belleville. His Initial Training School (ITS) in Toronto followed. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

When John arrived at Uplands in Ottawa in April 1941, he paid a visit to a local clergyman, the Reverend Frank Fidler, whose wife had been, since childhood, a friend of the nurse at Avon Old Farms School. John arrived early on a Saturday morning, Mrs. Marguerite Fidler recalled, and it appeared he’d had “a late night” on Friday. As Mr. Fidler was completing work on the next day’s sermon, John was asked to wait in the living room. Mrs. Fidler went about her work in the kitchen. After a few minutes, she poked her head around the corner to check on John; he was stretched out on the couch, fast asleep. When five-year-old Joan Fidler peeked in at the snoozing teen, Marguerite implored her “to let the boy sleep, he's tired." Eventually, John awoke, enjoyed some food, and the Reverend Fidler and John left the house for a quick car tour of Ottawa. John was dropped off at the base. But before he left the Fidler residence, John signed their guest book. Years later, the Fidlers learned that the young fellow who had napped on their couch was the teen pilot who wrote “High Flight.” The guestbook page became a family treasure. And Joan, in 2016, notes "I still have a vivid picture of him asleep on our chesterfield in the living room. Photo: Linda Granfield

A wonderful photograph of John Magee looking dashing, standing next to one of the Canadian Car and Foundry-built Harvard 2s of No. 2 Service Flying Training School at RCAF Station Uplands, Ottawa. Around his neck, he wears a helmet with Gosport speaking tube attached which was used in lieu of an intercom system to speak to the instructor in flight. The date is the early summer of 1941. Photo: DND

A posed photograph of American student pilots of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan at No. 2 SFTS Uplands, Course 25 in the spring of 1941. This was in the weeks leading up to the filming at Uplands of major sequences of Captains of the Clouds, Warner Bros.’ largest production to date. Starring James Cagney, the producers of the film looked to a premier in New York early in 1942. Contrary to some stories, Magee was not part of the filming of the famous wings parade scene in Captains of the Clouds. By that time, he had left for England. At left is Leading Aircraftman John Magee pointing to some lofty goal with posed determination and perhaps a bit of embarrassment. Perhaps this promotional shot was destined to inspire Americans to step up and get behind the Allies in the expedition of the war. While the film was in post-production, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor eliminated any need for the film to encourage the Yanks. Captains of the Clouds opened in February of 1942 but America hardly noticed, preoccupied as it was with war preparations. The pilots are (L to R): Aircraftmen John G. Magee of Washington (J5824); Arthur C. Young of Cleveland, Ohio; Claiborne Frank Gallicher of Tulsa, Oklahoma; Curtis Gilman Johnston of Chicago, Illinois; Arthur Bernard Cleaveland of Springfield, Illinois; and Ober Nathaniel Leatherman of Lima, Ohio. Photo: DND

16 June 1941—Leading Aircraftman John Gillespie Magee, still wearing the white cap flash of an airman in training, beams with pride and delight as he is pinned with his RCAF wings by Group Captain Wilfred A. Curtis, DSC and Bar at No. 2 Service Flying Training School, Uplands. It was one week after Magee’s nineteenth birthday. Curtis was a fighter pilot with the Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War. Photo: DND

Shortly after receiving his wings at Uplands, Ottawa, John traveled to Washington D.C. to visit his family before leaving for England. His father, no longer performing missionary work in China, was serving at St. John’s Church, “The Church of the Presidents,” across from the White House. In an interview for The Washington Post, John mentioned that in September 1939, he “had to get into it.” He told the reporter that he “was too young at 18 to qualify for the British Ambulance Corps [so] he packed up and left for Montréal. He was about to enlist in the Canadian army when he ran into some friends who persuaded him to join the air corps.” The day after the article ran in the Post, silhouette artist Florence Browning cut this portrait of John G. Magee Jr.; the “Errol Flynn” mustache so many of the Second World War air force service members sported is clearly shown. It is interesting to note that silhouettes are generally cut in pairs, with the black side of the two paper pieces facing one another for a picture and a reverse-image. Both of the silhouettes, never framed, are in the Magee holdings at Yale. One wonders for whom John intended them, if they had been held aside for him rather than mailed or delivered to an admirer, perhaps? The Washington visit before he left for England was the last time the Magee family saw John. Six months later he was dead. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

A casual moment at the barracks, England, 1941—likely at RAF Digby. Photo RCAF

John Magee’s personal photograph album includes this image of him and a Spitfire. “Big Shot!” is the caption John wrote—with all the humility a teen pilot can have! In an interview for The Washington Post just before he left Washington D.C., John said he was “happy at having won his wings, more so at the prospect of flying a Spitfire—the ultimate dream of every British flier, he said—and the prospect of ‘a little action.’ ” From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

A poor quality photo, but a proud image of John nonetheless. Here we see him in the cockpit of a 412 Squadron Spitfire as indicated by the squadron code VZ on the aircraft’s fuselage. This would have been sometime after he left No. 53 Operational Training Unit at RAF Llandow, Glamorgan, Wales in August. Magee joined 412 Squadron at RAF Digby, Lincolnshire on 23 September 1941. For the next two and a half months he mostly trained, but did participate in several combat ops and even got a shot at a Messerschmitt Bf 109. He flew the Spitfire on 80 occasions.

John selected this image from a photographer’s contact sheet with multiple portrait poses. It is the official Royal Canadian Air Force photograph most often seen accompanying “High Flight” materials. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

The fragile original copy of “High Flight,” in John’s handwriting. The poem appears on the back side of a page of a September 1941 letter sent to his parents in Washington D.C. The letter/poem was loaned to Archibald MacLeish, the Librarian of Congress, for an exhibition called “Poems of Faith and Freedom.” The loan became a gift to the American people from the Magees and “High Flight” is permanently housed in the Library of Congress. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

Magee leans casually and confidently against 412 Squadron Supermarine Spitfire Vb (VZ-B, nicknamed Brunhildë). Spitfire Brunhildë (AD329) was damaged by Magee on 5 November, suffering wing tip damage during a dodgy landing at RAF Wellingore. Photo via Stephen Fochuk/Robert Bracken

No one knew why John had named his Spitfire Brunhildë—that is, until a cache of his letters to “Regine” was sent to Rusty Maclean, the librarian at the Temple Reading Room, Rugby School, England. Historian Linda Granfield was asked to transcribe the letters because of her familiarity with Magee family handwriting. “I actually gasped aloud as I was typing this letter into the computer,” she reports. “There was the Brunhildë explanation right in front of me. Mystery solved!”—“I have called my Spitfire—not after you [Regine]-(nor for that matter after any other girl I know) – but Brunhildë, because if you’ve ever seen a Spitfire you are struck with two things about it—Power and Grace. Hence the Teutonic goddess. I am painting it in large German lettering along the side of the cowling so that if Jerry ever sees it he will realize that even the German deities are on our side now.” The remainder of the text on the same page is also interesting. It reveals what’s going on outside his window as John writes, and also reveals what’s important to a teen pilot. “While we were away on manoeuvres the Eagle Squadron took our place here. They are a grand bunch of fellows, but they are practically deafening me now. Their whole squadron is taking off in formation as I write. The sky is full of Hurricanes. Lovely formation, too. Incidentally I haven’t forgotten about those drink(s) you were going to have waiting for me on my return. I live in anticipation! Meanwhile be good, dear heart, and keep the home fires burning, Always Yours, John P.S. If you ever have a cigarette that you don’t know what to do with put it in an envelope and mark it “Magee” as we can’t get them over here!” Photo: Linda Granfield

Aviation artist Michael Martchenko’s vast collection of military pieces lent authenticity to this painting, one of the illustrations in High Flight: A Story of World War II, a biography of John G. Magee Jr. by Linda Granfield. The book was published in 1999. A teenage boy served as the model; he wore the clothing and carried the equipment, and chuckled when told who and what a “Mae West” was. Illustration: Michael Martchenko

“High Flight” was published in the St. John’s Church bulletin in December 1941, shortly after John’s death. For decades, the bulletin copy was believed to be the first public printing of “High Flight”; however, in 1998, Linda Granfield discovered the poem had been previously published, with errors, in The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, on 12 November 1941. Proud aunt Mary Scaife had sent it, with a note about John’s Royal Canadian Air Force service. The search continues for a possible, earlier, publication of the poem. Note: the 3 September 1941 date printed with the poem is the date of John’s letter to his parents; the poem was written on 18 August, according to flight information in John’s log. Did John Magee know the public had read “High Flight” in November? We don’t know. Photo: Linda Granfield

Michael Martchenko’s painting depicts the collision of John Magee’s Spitfire and Ernest Aubrey Griffin’s Oxford, 11 December 1941. John had hurried into the war, fearing, as other youths did, that the war would be over before he could do his bit. The United States joined the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii just days before John’s death. This illustration, based on reports of the actual collision, appears in Linda Granfield’s High Flight: A Story of World War II. Illustration: Michael Martchenko

RAF Leading Aircraftsman (LAC) Ernest Aubrey Griffin, like John Magee, was only 19 years old when he died. He had only been in the Volunteer Reserve for six months. His mother and Faith Magee corresponded when each learned the identity of the other’s son. Griffin is interred at the Oxford Crematorium, Headington (formerly Stanton St. John), England. There his name appears on a Memorial Wall panel.

The telegram received by the Magee family in Washington D.C. The censored portion is the street address of the family, a house rented while the Reverend Magee served at “The Church of the Presidents” during the Second World War. Within weeks of being notified of John’s death, the family received letters of condolence from the general public, and from others, more famous, who also had been touched by their son’s poem. Among those who sent notes were Helen Keller, actresses Katherine Hepburn and Merle Oberon, and members of the American government. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

The Magee family received this photograph of John’s grave in England. The simple cross in Scopwick Cemetery in Lincolnshire was later replaced by one of the uniform Portland stone grave markers installed by the Imperial War Commission (now known as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.) John Gillespie Magee Jr. is buried with other Royal Canadian Air Force airmen who died while serving at the Digby aerodrome. As did other parents, the Magees selected the inscription to be carved on their son’s stone—two lines from “High Flight.” “Oh, I have slipped/The surly bonds of Earth…/Put out my hand/And touched the face of God.” From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

In June 1943, artist Jere Wickwire, a Yale classmate of the Reverend Magee, painted a portrait of young John based on his RCAF portrait. The Magee family posed with a preliminary drawing for the portrait, a gift to them from the artist. Faith Magee is wearing the purple-ribboned “Mother’s Cross” (Memorial Cross). David had enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. Christopher (back) served in the Combat Merchant Marine during the war. Hugh (left) was a student. In 2012, David Magee gave the signed artist’s sketch to the Canadian War Museum (Ottawa) as a gift from the family to Canada where John had trained and whose uniform he wore. The finished oil painting hangs at Rugby School in England. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library

“High Flight” has inspired creators in many disciplines. It has been set to music, used in fiction and film, and written on walls, furnishings, and paintings. During the Second World War, the Citizens’ Committee for the Army and Navy commissioned artists to design and execute altar triptychs. These collapsible screens could be carried into the field or on board ship in order to make a “pop-up chapel” for the troops. This “High Flight” triptych was painted by Alfred James Tulk (1899–1988) for the existing chapel at Bolling Field, Washington D.C. It was unveiled by the Magee family in 1946 but was, unfortunately, destroyed in a fire just a few years later. Rumour has it that a photograph of John Magee served as the model for the young Christ’s face; however, no confirmation of this has been found. Image source unavailable

For many Canadians, the Grade Five reader entitled “High Flight” was their first encounter with the teen pilot’s poem. The publishing company, Copp Clark Co. Limited in Toronto, received written permission from “[the] Reverend and Mrs. John G. Magee” to include the poem in the 1951 publication. Lines from “High Flight” appear on the frontispiece and the entire poem is on page 8, in a section called “Growing Up in Canada.” An asterisk (*) indicates Canadian authors; John’s name has no asterisk. That said, he is in the immediate company of Robert Frost, Rudyard Kipling, Rt. Hon. Vincent Massey (“On Being Canadian”) and Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. And that’s just the author list of the first section. Photo: Linda Granfield

Another example of “High Flight” inspiration is the altar in the Trinity College Chapel at the University of Toronto. Gordon Peteran’s 1994 design includes lines from “High Flight” etched into the top surface. The altar was a gift of the class of 1944 in memory of their fellow students who died in the Second World War. It is apt that within a Gothic room filled with soaring stained glass windows and a palpable peace, where students and faculty pray and weddings and lives lost are celebrated, the timeless words of a young pilot who never had the opportunity to attend university wing their way into hearts and souls. Photo: Linda Granfield

A graduate of Yale University, Frederick Hugh Magee (Hugh) trained for Ordination at Westcott House, Cambridge. He was ordained in 1959 and has since served parishes on both sides of the Atlantic, and as Dean of Wenatchee in the Diocese of Spokane. Recently retired, Hugh remains an Honorary Canon of the Episcopal Cathedral in Dundee, Scotland, where he served for fifteen years. In addition to his priestly duties, Hugh has for the past thirty years been a student of A Course in Miracles, a teacher, and a writer. He lives with his wife Yvonne, a fine artist/painter, in Scotland. Photo: Linda Granfield

In December 2011, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of “High Flight” and John Gillespie Magee Jr.’s death, ceremonies were held at his grave. Among the tributes placed on the grave were a poppy wreath, flags, and a pressed maple leaf sent from Canada. Hugh Magee attended the ceremonies at the Scopwick Church Burial Ground, in Lincolnshire, England. Photos: Left and centre: via Hugh Magee; right via Panaramio

Initial Training School classmate and Uplands contemporary of John Magee Jr., Flight Lieutenant Fred Jones climbs his all-blue Spitfire PR into the burning blue in England in 1944. Jones was one of the first cadre of young pilots to know and cherish Magee’s poem. High Flight was read at his funeral by his son-in-law, Dave O’Malley in 2007. Photo via Rosemary Jones

![John mentioned to a newspaper reporter that in September 1939 he “had to get into it [the war.]” He said that he “was too young at 18 to qualify for the British Ambulance Corps [so] he packed up and left for Montréal. He was about to enlist in the Canadian army when he ran into some friends who persuaded him to join the air corps.” The New Paramount Portrait Studio in Toronto (still in operation) photographed many of the Royal Canadian Air Force recruits. In 1940, John Magee, sans mustache, sat for his first military portrait. Via Manning Depot No. 1 in Toronto, he’d soon be acquainted with the “Horse Palace Cough,” as he slept with hundreds of others in bunk beds set up in the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) grounds near Lake Ontario. The nearby boardwalk and dance halls provided diversions for John and his new air force friends. From the Magee Family Archive/Yale Divinity School Library ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1626998385770-8F5C734TZC208VVBEB7X/HighFlight75_16.jpg)

![For many Canadians, the Grade Five reader entitled “High Flight” was their first encounter with the teen pilot’s poem. The publishing company, Copp Clark Co. Limited in Toronto, received written permission from “[the] Reverend and Mrs. John G. Magee” to include the poem in the 1951 publication. Lines from “High Flight” appear on the frontispiece and the entire poem is on page 8, in a section called “Growing Up in Canada.” An asterisk (*) indicates Canadian authors; John’s name has no asterisk. That said, he is in the immediate company of Robert Frost, Rudyard Kipling, Rt. Hon. Vincent Massey (“On Being Canadian”) and Sir Charles G.D. Roberts. And that’s just the author list of the first section. Photo: Linda Granfield](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1626999678022-KDW7HS47MQ82L4NLCWBN/HighFlight_45.jpg)