THE MOTHER OF ALL DRONES

These days, when one thinks of drone aircraft, one conjures up an image of a sinister, beluga-shaped monster, whispering along at 20,000 feet on a moonless night over Iraq or Afghanistan. Inside its featureless head, synthetic aperture radar and unblinking infrared eyeballs whir, rotate, scan below and beam information to someone in an air-conditioned building in middle America.

Down below, beamed to the other side of the world in infrared, creeping Orwellian voyeurism, a group of Taliban fighters lope across a sandy plain like spectral ghosts. As they move, the silent, red, watching eye 20,000 feet above follows them. They cannot feel its stare as it is inanimate. A continent away, a controller, wearing military clothing and unit patches, selects a high magnification and the Taliban jump into focus as they enter a compound through a break in a dirt wall. Radio communications whip back and forth across the world, permissions are sought and granted, voices chat calmly. Then a white flash obliterates the images on the screen.

The image can’t help but make one cringe just a bit, despite our distaste for the terrorists below. The removal of the human from the close delivery of death leaves a strange feeling in the heart. The voices of the controllers don’t have the high pitch of someone whose very life is threatened in the execution of a war. They speak in tones one would imagine a crane operator or ferry captain might use as he or she goes about a technical, workman-like job. Even the very name of “drone” itself brings to mind a mindless animal doing the bidding of a master somewhere.

The drone now occupies an ever-growing space on the battlefield. Its utility is undeniable. The high-tech, Terminator-like image of drones belies a history that goes back nearly 100 years, to the earliest days of powered flight and even before.

As early as 1849, the Austrian ship Vulcano attacked the besieged city of Venice (then a republic) by launching unmanned balloons carrying explosives. The Viennese newspaper Die Presse reported in advance of the impending aerial bombardment, stating “Venice is to be bombarded by balloons, as the lagunes prevent the approaching of artillery. Five balloons, each twenty-three feet in diameter, are in construction at Treviso. In a favourable wind the balloons will be launched and directed as near to Venice as possible, and on their being brought to vertical positions over the town, they will be fired by electro magnetism by means of a long isolated copper wire with a large galvanic battery placed on a building. The bomb falls perpendicularly, and explodes on reaching the ground.”

The first attempt was an abject failure and Time magazine reported an account of the event (much later of course): “The balloons appeared to rise to about 4,500 ft. Then they exploded in midair or fell into the water, or, blown by a sudden southeast wind, sped over the city and dropped on the besiegers. Venetians, abandoning their homes, crowded into the streets and squares to enjoy the strange spectacle. … When a cloud of smoke appeared in the air to make an explosion, all clapped and shouted. Applause was greatest when the balloons blew over the Austrian forces and exploded, and in such cases the Venetians added cries of ‘Bravo!’ and ‘Good appetite!’ ” Reading these two passages now, one realizes that not much about the unmanned aerial weapon concept has changed, except the efficiency of it all.

When the 20th Century rolled around and brought with it the emergence of the powered flying machine, it wasn’t long before the unmanned concept was dabbled with once again. The First World War sped the development of machines, training, tactics and anti-aircraft systems. There were situations in which pilots were at greater risk when attacking. Delivering a torpedo, for instance, required a flight path of unflinching constancy for minutes at a time (in the First World War at least), while newly designed and specialized gun platforms focused on the oncoming and lumbering threat. Flying deep into enemy-held territory to deliver a bomb put pilots at great risk where air superiority was in the hands of the enemy.

One of the first and best known of the very early powered and unmanned flying machines was the Kettering Bug, a small biplane flying “torpedo” which flew in a set direction... up to 120 kilometres from its launch point. It raised many possibilities but was too unsophisticated and too late to have made any impact on a war where new technologies were emerging weekly.

The Kettering Bug, designed to deliver a nasty mix of phosphine gas and high explosives, had many design flaws and by the time the weapon had achieved even a modicum of success, the war had ended and production was never begun. Click here to see the Kettering Bug’s development comical failures and eventual but erratic flying success. Photo: US Army

Further development of pilotless aircraft continued, albeit weakly, after the First World War in both America and Great Britain, but it was the British Royal Navy and Royal Air Force that truly pushed the technology to its first true successes. The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and the Navy teamed up in 1925 to produce and test the world’s first “cruise missile” known as the RAE Larynx (a contraction of the words “Long Range Gun with Lynx Engine”). Larynx aircraft, looking decidedly modern compared to later pilotless aircraft, were launched two years later from a cordite-fired catapult on the forward deck of the Royal Navy destroyers HMS Stronghold and Thanet. Conceived as a long-range anti-shipping weapon, the Larynx was powered by a 200 hp Armstrong Siddeley Lynx engine and, with its 200 mph top speed, was faster than contemporary fighters. Only seven were launched during the test program, and the aircraft never saw production.

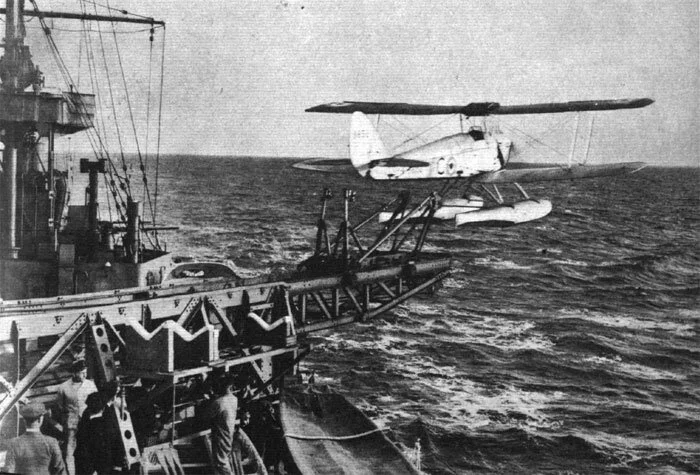

Two views of the Larynx pilotless and radio-controlled aircraft on the forward deck of HMS Stronghold, showing its high visibility paint scheme designed to keep it in view as long as possible. The first launch ended in disaster with the Larynx crashing into the Bristol Channel after only a few minutes. The second flight was far more successful, with a Larynx flying more than 100 miles before it was lost. The third flight went 112 miles and came down just five miles from the intended target—a promising result. Photos via AirWar.ru

Related Stories

Click on image

In 1932, the Royal Navy saw the need for a realistic anti-aircraft gunnery target for anti-aircraft training—one that could take off, fly back and forth in front of the gunners and then be recovered and reused if not destroyed. At that time, flying targets were usually towed by piloted aircraft requiring a somewhat restrained approach to shooting to avoid hitting the tow aircraft. A pilotless aircraft would present a much more realistic target.

The first attempt by the Royal Navy to create a radio-controlled pilotless aircraft capable of taking off, flying and landing was the Fairey Queen, a decidedly unmilitary name. The Fairey Queen, a variant of the Fairey III reconnaissance biplane, was to be used by Royal Navy warships as a gunnery trainer... an expendable target. The Queen had an increased dihedral over the standard Fairey III, designed to improve her lateral stability for remote control. Only three were built and all were launched from HMS Valiant. The first two, including the one pictured below, set to launch from the stern of Valiant in April 1932, were lost when they crashed immediately into the sea (their flights were 18 and 25 seconds respectively). The third was successful and was recovered on the sea after its flight in September 1932. It was hoisted aboard Valiant and launched again in January of 1933 at Gibraltar whereupon the Home Fleet fired away for two hours, failing utterly to even damage the Queen. It landed safely on the Mediterranean after all ammunition was exhausted. The following May, the gunners of HMS Shropshire dispatched the Queen in just 20 minutes at Malta.

The limply-named Fairey Queen aboard HMS Valiant is cocked and ready for launch from her stern. While somewhat of a failure, the Fairey Queen led directly to the de Havilland Queen Bee, the mother of all drones. Photo: Royal Navy. Reference: Fairey Aircraft Since 1915 by H.A. Taylor

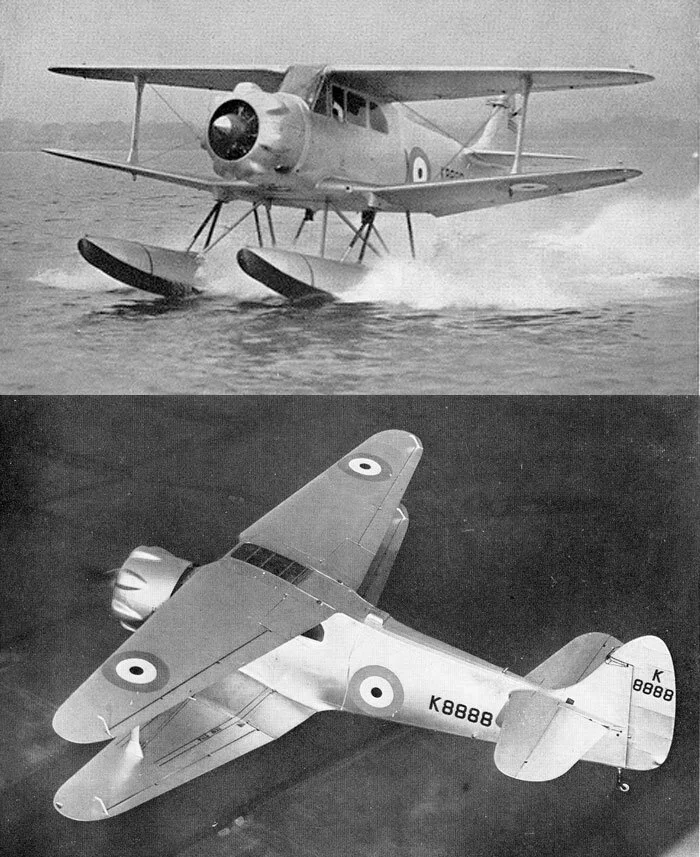

The experience with the Fairey Queen, while limited, led to the need for a production target aircraft for anti-aircraft gunnery training and eventually the development of the de Havilland DH-82B Queen Bee, the first full production, full-sized, reusable, pilotless aircraft. To the casual observer, the Queen Bee looked almost exactly like a de Havilland DH-82A Tiger Moth, but in truth it was a mash-up aircraft using the lighter, more buoyant wooden fuselage construction of the DH-60 Moth combined with the higher dihedral wings of the Tiger Moth. The aircraft could be operated remotely by another pilot or controller sitting in another aircraft, on a warship or from a control panel on land. It could operate from runways or be shot from catapults, to be recovered on floats.

The control panel utilized a simple rotary dial, using which, the controller could “dial in” a radio-transmitted command. Numbers on the dial represented commands such as “turn left, turn right, pitch-up,” etc., while additional controls operated ignition and throttle. While the control panel was relatively small, the radio transmitter itself was the size of a delivery van. The front cockpit had these same controls, enabling a test pilot to check the pilotless functions of the aircraft at altitude. The radio commands operated a series of pneumatic servos housed in the space once occupied by the rear cockpit. The design did not allow for coordinated flight using the ailerons and rudder, so the ailerons were always locked in the neutral position. Controllers used only the rudder, elevator and throttle controls.

The Queen Bee represented a major step forward on many fronts, not the least of which was radio-control. One of its immediate, if disappointing, benefits was that it revealed shortfalls in the skills and efficacy of Royal Navy anti-aircraft gunners and systems. It was not uncommon for a Queen Bee to parade up and down in front of an entire warship squadron for over an hour while they pounded away at it, only to be commanded to land without a scratch. There is even an account of the King witnessing a demonstration of Royal Navy gunnery prowess using the Queen Bee, during which the gunners were unable to hit it. One high-ranking officer was seen to turn to his subordinate and whisper “For ***** sake, tell the operator to dial SPIN”, at which point the Queen Bee dove into the sea, seemingly the victim of the gunners. The Royal Navy, British Army and Royal Air Force would utilize the Queen Bee to great extent to improve gunnery results, but the Navy soon turned to new technologies such as radar range finding and primitive computers to make warship anti-aircraft weapons the equal of modern dive and torpedo bombers.

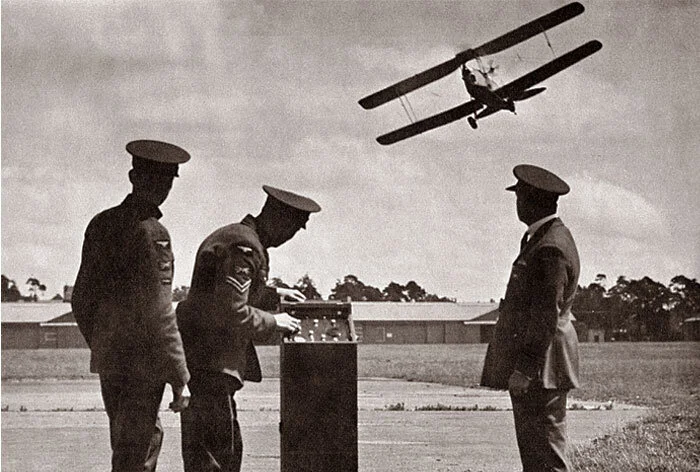

Two photographs of de Havilland Queen Bee K4227, one of the first 10 production models (Number 7), at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough. We can clearly see the ram air turbine mounted on the port side of the fuselage aft of the engine, which powered the pump that provided compressed air to the remote control system housed in the space where the instructor pilot would have sat in a Tiger Moth. These views give us a good idea of how the early aircraft were configured for pilotless flight. Tonneau covers help streamline the cockpits, which were still required to do factory test flights and delivery to launch sites. It is believed that these early production models were painted overall in silver. Photos: Royal Air Force

A photograph of an early example of a Queen Bee. This is quite possibly K4227, the early production Queen Bee featured in the previous two photos, but her serial numbers are hidden from the photographer. K4227 was very much in the public eye in June 1935 as she put on a flight demonstration at Farnborough, taking off, flying, manoeuvring and landing, all under remote control. The British Air Ministry did not allow pilotless aircraft to fly over populated areas, so test pilot Flight Lieutenant C.M. Vincent, DFC had to sit in the cockpit throughout the entire flying demonstration to guarantee control in the event of a loss of radio control. Researching the de Havilland Aircraft Production lists in the web, it is stated that K4227 crashed on 17 July 1935, just a couple of weeks after it was successfully displayed at the Farnborough Air Show. Photo via Gloucestershire Transport History

The same aircraft as in the previous photograph has now attracted some airmen. Photo: RAF

I believe it is fairly likely that the de Havilland DH-82B got its name partially from its progenitor, the Fairey Queen, for their developments were linked. Geoffrey de Havilland was a passionate amateur entomologist, and liked to name all of his early aircraft after flying insects (Tiger Moth, Fox Moth, Mosquito, and Dragonfly), so likely chose its Queen Bee name for the connection to the Fairey and to the fact that it was the “B” model of the DH-82.

The Queen Bee was certainly the first truly successful pilotless aircraft with nearly 400 being manufactured over several years. The Queen Bee’s ability to fly without a pilot was indeed high technology at the time and it was demonstrated for dignitaries on many occasions. In 1936, Admiral William Harrison Standley, the US Navy’s representative at the London Naval Conference, was witness to a demonstration of the Queen Bee during a live-firing exercise. Upon his return to the United States, he set in motion revitalized American research into remotely flown aircraft like the Queen Bee, which could be used as a training device in the same manner.

Shortly thereafter, the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) tasked Lieutenant Commander Delmar Fahrney to lead a project to develop the system. Within months, two Curtiss N2C-2 Fledgling and two Stearman training biplanes were equipped with similar equipment to the Queen Bee. Soon, the word “drone” began appearing in documents related to the American project. According to accounts, Fahrney himself coined the term drone as a deliberate nod to the de Havilland Queen Bee.

It is not known for sure if the drone naming is fact, but it is likely. Certainly, it is an appropriate name, conjuring armies of identical, mindless animals whose sole purpose is to do the bidding of a Queen Bee mother. Regardless of the source of the new name, it stuck like honey to a picnic blanket! Before the arrival of the Queen Bee, there were certainly other attempts at birthing the remotely flown aircraft, but they were largely aborted, miscarried, stillborn or short-lived. The Queen Bee produced nearly 400 offspring and generations upon generations of evermore capable aircraft flown by operators who stand off a world away. Today, drones can do almost anything from delivering pizza to occupying the nightmares of terrorists everywhere. Any one of us can own one. They range in size from mere inches to 150-foot wingspans. They can fly for days on end and for thousands of miles. They present complex moral conundrums about the sanitized delivery of death, about who is a combatant, and many more. One thing for sure is that, as the presence of drones on the battlefield grows, the need for heroes diminishes. Using drones, the execution of a war now requires less from a country. Fading fast are the simple values of duty, honour and above all sacrifice. Of all the efficiencies, capabilities and benefits found in the modern combat drone, one of them is NOT the ability to inspire.

While much has developed, not much has changed in the 80 years since the development of the delicate contraption known as the Queen Bee. She is indeed the Mother of all Drones.

Dave O’Malley

A Royal Air Force corporal demonstrates the controls of a de Havilland DH-82B Queen Bee, while an officer pilot looks on. Flying the Queen Bee at such a low altitude using the control panel required considerable skill. In this photo we can see the wind generator or Ram Air Turbine (RAT) attached to the port fuselage just aft of the engine cowling. The turbine powers a pump which provided compressed air in flight to the pneumatic servo actuators in the fuselage, which in turn moved the controls. Photo: RAF

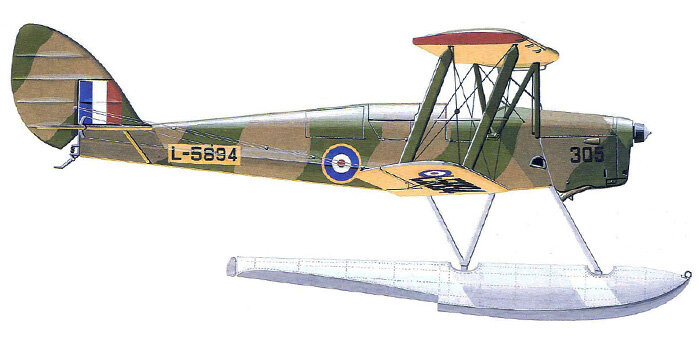

Though Tiger Moth Queen Bees had been in use for some time, Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited a launch site at the Weybourne Anti-Aircraft Artillery Range on the Norfolk coast on 6 June 1941 with Secretary of State for War David Margesson (behind). Here, the unpiloted Queen Bee L5894 is readied for launch from a steam catapult. Navy gunners were unable to or perhaps did not attempt to shoot down this particular drone during the demonstration, for L5894 was listed in de Havilland production logs as having been shot down off Weybourne 12 days later. Churchill made two visits to the range in 1941. During his first visit, a demonstration of projectile firing was carried out, but the result was most unsatisfactory. The Prime Minister gave the commandant just seven days to improve the standard. On the second visit, each demonstration repeatedly ended in failure until finally, a Queen Bee target aircraft was shot down and crashed close to the VIP enclosure. Local history has it that all the senior staff were replaced the following day. Photo via Imperial War Museum

An aerial view of Weybourne today, showing her grass runways where, 75 years ago, Queen Bees were flown in for launching either from the grass or from the steam catapult shown in the previous photo. There are several such coastal artillery ranges where anti-aircraft gunners were trained using both towed targets and unmanned Queen Bees—Watchet, Somerset; RAF Manorbier, Pembrokeshire; Burrow Head, Scotland; Aberporth, Wales; RAF Cleave, Cornwall; and many more. The circular concrete pad at centre left is one of two round bases for the Queen Bee steam catapults used at Weybourne. Photo: Daniel Nicholson

A profile drawing of the very same de Havilland DH-82B Queen Bee as used in the demonstration for Winston Churchill. Note the red undersides of the upper wingtips—applied to later production models and used to help gunners see the angle and direction of flight at a distance. A steam catapult was used when the aircraft was launched on floats. Image via WingsPalette

A restored de Havilland Queen Bee LF858 in England, the only flying example. Note the red undersides of the top wing tips, designed to assist controllers better visualize the flight of the aircraft—the pilotless aircraft had to remain in sight of the controllers to be effectively flown. The aircraft is now operated by Captain Neville’s Flying Circus. The website for this operator explains the history of this Queen Bee: “This Queen Bee, RAF Serial No. LF858, civil registration G-BLUZ, is one of about 70 machines built under licence by Scottish Aviation in Glasgow in 1944. It saw service in the Second World War at RAF Manorbier in Wales, and after the war changed hands several times before being involved in a landing accident at Old Warden, Bedfordshire, following which it was stored there by the Shuttleworth Trust for many years. In 1983, it was sold to Barrie Bayes of Cranfield, who over the course of the next four years undertook a full restoration of the aircraft, including a full rebuild of its de Havilland Gipsy Major engine. The rear cockpit has now been fitted with dual flying controls. This particular aircraft is believed to be now the world’s only airworthy example of its type. The Queen Bee is currently based at RAF Henlow in Bedfordshire, and has since 1995 been owned and operated by a six-man syndicate known as ‘The Beekeepers’ flying group”. Photo by Adrian Pingstone

Many of the same technologies and techniques are still employed by drones today including catapults and the painting of wingtips and control surfaces in bright red or orange to assist controllers in visualizing the orientation of the aircraft. Here we see the old Queen Bee paint technique applied to a QF-100 Super Sabre pilotless target drone at top and recently to the QF-16 Fighting Falcon target drone. Photos: USAF

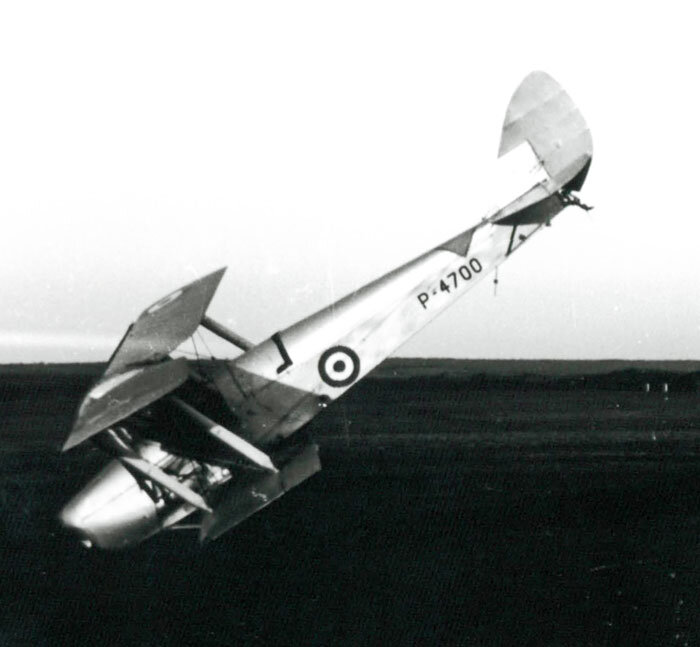

The Queen Bee also utilized an automatic landing system, designed for when radio control was lost. This system employed a long trailing and weighted wire antenna which sensed when the aircraft was near the ground or water. If control was lost, then the aircraft would fly on until it ran out of fuel. Then it would glide to earth, sense when it was close and the onboard automatic system would take over, shut off the magnetos if they were still operating, select an elevator position for a landing flare and land the Queen Bee. Here we see a Queen Bee that has landed automatically at RAF Cleve in 1940. This aircraft (P-4700) survived this difficult landing and was eventually shot down into the sea at the gunnery range at RAF Manorbier on 5 March 1943. Photo via No2 A.A.C.U. at The Aviation Forum

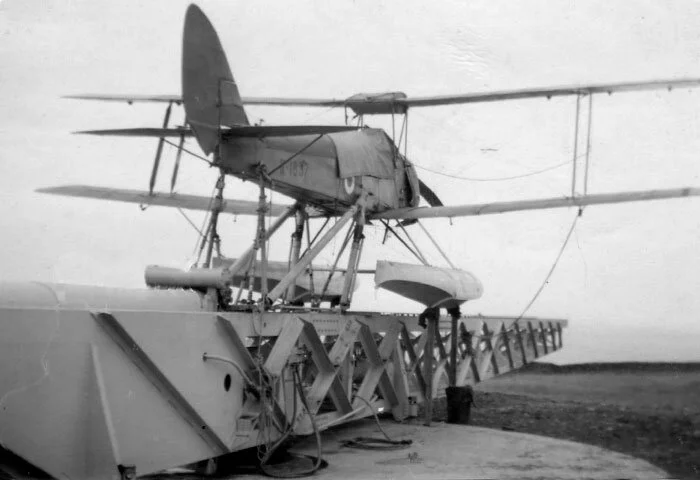

A Queen Bee on floats sits in the cradle on the steam catapult roundtable at the Burrow Head Anti-Aircraft Artillery range in Scotland. The catapult could be rotated to point the Queen Bee directly into the wind. This particular Queen Bee, serial number N1837, crashed into the sea off Burrow Head on 20 July 1939. Photo by Roy Eldridge

The catapult at Burrow Head, used for launching Queen Bee pilotless target aircraft. The ram air turbine, used for generating power for the pneumatic pump, can be seen clearly on the port side of the fuselage. Photo by Roy Eldridge

A dramatic photograph of a pilotless de Havilland DH-82B Queen Bee rocketing from the steam catapult at Burrow Head. From July 1939 to April 1942, a total of 46 Queen Bees were launched at Burrow Head, the bulk of them flown off the grass strip at nearby RAF Kidsdale. Photo: Roy Eldridge

Another pilotless Queen Bee (L7723) leaves the cradle of a steam catapult at a firing range. Many of the Queen Bees were flown more than just the single time, some operating for months. It is hard to tell where this is, but L7723 was lost when its floats collapsed at Malta on 24 October 1939. Photo: everythingexmoor.org.uk

The only remnant of the Queen Bee program at RAF Cleave in Cornwall today is the concrete base upon which the catapult was rotated into the wind. Image via derelictplaces.co.uk

There are few photographs extant of Queen Bees in operation from the 1930s and 40s. The best ones seem to have been taken during formal visits of politicians to military facilities where the radio-controlled aircraft were employed, as in the previous image of Churchill and Margesson at Watchet. This photograph of Queen Bee N1841 was likely not taken during the demonstration put on in August of 1938 for Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State at the War Office. Hore-Belisha was accompanied by British military brass, 16 mayors of London boroughs and some 50 Members of British Parliament, a testament to the notion that the Queen Bee was considered leading edge technology at the time. For an amazing newsreel video of another Queen Bee (K6664) being launched for Hore-Belisha and shot down, click here. The anti-aircraft artillery gunnery range at Watchet was along the Somerset Coast, a few hundred metres to the east in Doniford. The gunners at the Doniford gun park shot at targets towed by aircraft flying out of RAF Weston-Zoyland and Queen Bee aircraft shot from the catapult shown in this photograph. At first, the Queen Bees were launched from the cruiser HMS Neptune anchored off Watchet, but were later catapulted from the Doniford range and could be flown remotely to avoid being hit. However, when hit they would crash into the Bristol Channel, there to await wreckage recovery by SS Radstock, operating from Watchet harbour. Queen Bee N1841, pictured here, was eventually shot down by gunners a year later on 7 June 1939. Photo/information via www.watchetmuseum.co.uk

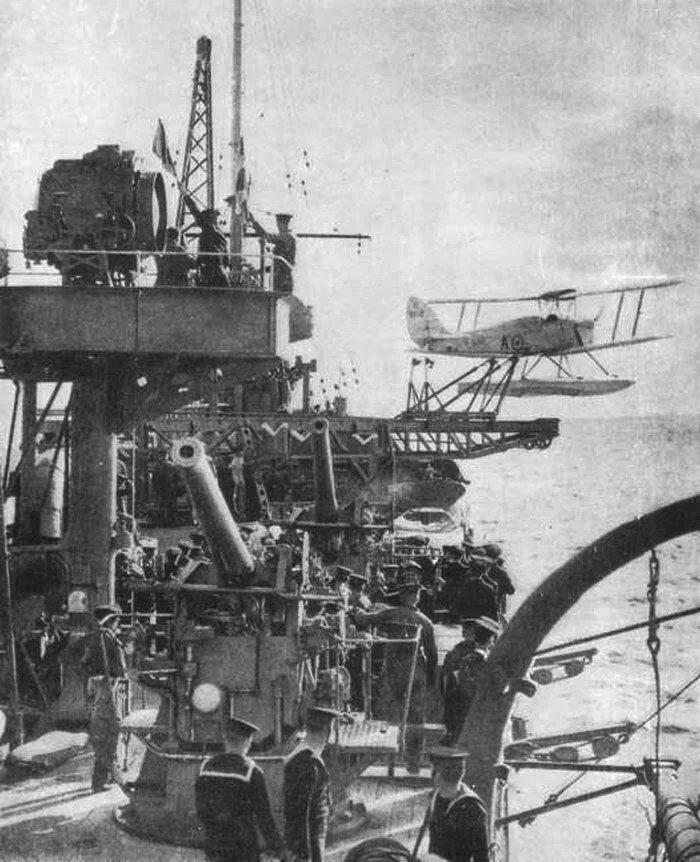

A de Havilland Queen Bee launches from the waist catapult of the Leander-class light cruiser HMS Neptune, which participated in tests and exercises in the Bristol Channel. Photo: Royal Navy

HMS Neptune launches another Queen Bee. Note the sailors congregating on her decks to watch the launch as well as her quick-firing 4-inch Mk IV guns along her sides and trained aft. It is not known whether these guns were employed against Queen Bees, but they were highly capable naval, coastal defence and anti-aircraft guns—capable of reaching aircraft at 28,000 ft. Photo: Royal Navy

The old Bristol Channel coastal steamer SS Radstock was employed at Watchet, recovering both the wreckage of downed Queen Bee drones as well as those that landed safely on the water. Here she ties up at Watchet with a recovered Queen Bee resting on her cargo deck. HMS Neptune could also recover her own Queen Bees directly with her own cranes. Photo: watchetconservationsociety.co.uk

A Queen Bee takes off along a coastal scene that seems somewhere other than Great Britain. The Royal Navy operated Queen Bees from Royal Navy Air Yard (RNARY) Fayid on the Suez’s Great Bitter Lake, RNARY Dekheila near Alexandria and Ta Kali on Malta. Photo via topwar.ru

With the relative success of the early Queen Bees, Airspeed Limited designed the lovely Airspeed AS.30 Queen Wasp in 1937. Only five prototypes were built and, although intended for both Royal Air Force and Royal Navy use, the aircraft was fated not to go into series production due to lack of expected performance. She may have been too lovely to shoot down. Photos via Wikipedia

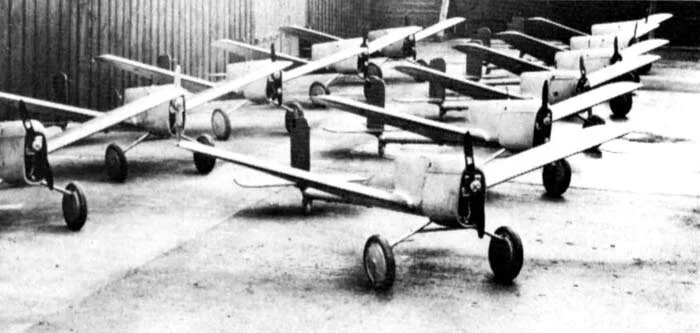

Radio-controlled pilotless aircraft were under development in more than just Great Britain. Some of the “early adopters” included the United States and Nazi Germany. The Germans investigated and eventually produced a number of small un-piloted target and reconnaissance aircraft called the Argus As292. Here a dozen or so of the more than 100 German-built mini-aircraft sit on a hangar floor. The type was fitted with a Zeiss cine camera for reconnaissance work and, when the mission was over, a radio signal shut the motor off and deployed a parachute to allow them to descend to earth. Photo: luftarchiv.de

Pilotless aircraft seemed to draw dignitaries in every country, perhaps due to the science fiction-like qualities. Here a group of Luftwaffe and Nazi big wigs, including First World War ace Ernst Udet, standing at centre, look rather unconvinced as they stare down at a diminutive Argus robot airplane. One would love to know what the great pilot thought of a future without him. Today, Germany is one of the great producers of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles or Drones, as we have now come to know them. Photo: luftarchiv.de

Jet-powered Firebee target aircraft are stored inside a Teledyne-Ryan service hangar in 1984. By this time, pilotless aircraft used for targeting and reconnaissance were now called “drones”. The Ryan Firebee was a series of target drones developed by the Ryan Aeronautical Company beginning in 1951. It was one of the first jet-propelled drones, and one of the most widely used target drones ever built. In the late 1990s, Teledyne-Ryan configured two Firebees with cameras and communications equipment to feed real-time battlefield intelligence for targeting and damage assessment. In an ironic twist, these drones were named “Argus”, possibly as a nod to its diminutive German predecessor, the Argus As292. Photo: USAF

Typically, Firebee target drones were released near the firing range from motherships like this US Navy DC-130A Drone controller, capable of carrying four underwing Firebees. The US Navy’s Herc motherships operated from the Southern California Operating Area, flying missions from NAS North Island and Point Mugu. The DC-130 could launch, track and control the Firebees in flight. Photo: PHCS R.L. Lawson, USN

Two shots of Royal Canadian Air Force drone carriers hefting two Firebees at a time in operations at Cold Lake, Alberta. Photos: top: RCAF, bottom: RCAF via Bill Ewing

Today, the pilotless aircraft (a.k.a. Drone, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), and Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA)), dominates the battlefield, the press and moral arguments with scores of designs providing attack platforms, stealthy reconnaissance, air quality monitoring and a myriad of uses from pizza delivery to Arctic sovereignty monitoring and firefighting. They range in size from 10 inches and a hundred dollars to the 130-foot wingspan, $130 million RQ-4 Global Hawk (above) from Northrop Grumman. Photo: Northrop Grumman