PERMANENT INK — The Art, the Pain and the Glory of the Aviation Tattoo

If you have an aversion to displays of blotchy skin from ordinary people; if a man’s hirsute armpits frighten you or you have been living on an otherwise uninhabited island and not yet realized that the once-marginalized art of human tattooing is now an omnipresent social phenomenon that has grown to become part of the social fabric of western culture, then I suggest you do not press on with reading this article.

Let’s be perfectly honest here. I am a 67-year-old man, paunchy around the edges, with an ever-expanding universe of liver spots, fading in self-esteem and I come from a postwar era when non-societally-mandated tattoos were found only on men who inhabited the fringes of acceptable behaviour. There were, of course, societies and cultures on other continents whose culturally important tattooing practices I could view in National Geographic, but the only tattoos I came in contact with seemed to be curiously menacing, largely blurred and faded “pick and poke” concoctions that fit into one category—they all could be traced back to some sort of past military, penal or merchant marine service.

In 1973, as a young 20-something “town planner” assigned to do a facilities survey of Canadian Forces Base Petawawa about 100 miles northwest of Ottawa, I was assigned officer status. I lived in the BOQ and dined at the officers’ mess. Here, as a long haired, snot-nosed civilian puke with no apparent mojo and dressed in flared pants and platform shoes, I was served at the linen covered dinner table of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery Mess by 50-something stewards with lengthy military careers written in the lines of their faces—thirty years of heavy smoking and alcohol abuse. As they leaned in to take my plate or pour me another glass of ice water, their tattooed arms would pass before my eyes, drawn across them blue, barely understandable tributes to places, women, events and units they once loved—Latin phrases, waving flags, hangman’s nooses, daggers dripping blood, the crudely etched names of places I had only heard of (Subic Bay, Kyrenia, Shilo, Marseilles), the names of ships long ago scrapped (Haida, Swansea, Qu’Appelle) and the names of women once loved (Rose, Paulette, Sweet Cindy). These men represented the outermost ring of my existence—men who had served in Cyprus; men who had sweated months in a Ferret scout car in the Gaza Strip; men who had travelled the Pacific Rim on some long-forgotten navy tour, never getting deeper into these places than the fleshpots and hard-bitten waterfront dives of places like Manila, Mombasa, Gibraltar and Liverpool. It was evident to my eyes, fresh from 5 years of architectural training, that these were executed by some of the least talented artists known to man.

In 1976, as an assistant to a National Geographic photographer, I boarded the 300-foot icebreaking cargo freighter MV Bill Crosby bound from Montréal, through the Straits of Belle Isle, to Hall Beach on the shores of Foxe Basin—one of Canada’s remotest spots. It was late October and this was to be the last voyage north with supplies for isolated Arctic communities. The crew, save for two young French Canadians, were from Newfoundland and had made their living upon the sea for decades. Nearly all wore tattoos on their forearms, their knuckles or their shoulders. I shared a bottle of whiskey one night with one particularly rough fellow while the ship hove to and rode out a heavy storm off Cape Chidley, Labrador. A chief steward, his “office” was directly behind the galley and right beneath the overhead, where a lashed and massive Caterpillar generator ran at full bore. The cabin was filled with the smell of diesel, bunker oil, fried caplin, paint, vomit and body odour. The temperature was unbearably hot despite the dark icy waters and thrashing arctic storm outside. The ship rolled and pitched violently and the windowless cabin rose and fell forty feet for hours on end. The steward sat at a table upon which he leaned his elbows and filled his and my glass after every shot. On one forearm he wore a tattoo of some vague and blurry coat of arms while on the other was a tattoo featuring two large dice (a pair of sixes) and the word “Boxcars” and the letters “HMP” (Her Majesty’s Prison, in St. John’s).

As we got drunker, his tragic and disturbing story started to leak out of his mouth like a confession. By the time we were near the bottom of that bottle of Jim Beam, he had admitted to me that he had just gotten out of prison where he had served 6 years for attempted murder having botched the shotgunning of his girlfriend in his home. “A crime of passion.” he repeated before he downed each of his last three drinks. By this time, being destabilized by the storm, the overhead roar of the diesel, my murderous friend’s admission, the oven-like heat of the steel box we were drinking in, and eight whiskies I had consumed, I started to fear for my life. Before I staggered out of there, all I could see were his forearms and those blurry, crude and menacing tattoos.

Perhaps now you will understand why, in the 1980s, when tattooing started making inroads into middle class society through frat boys and debutantes, I became alarmed at the practice. I, like many of my generation whose young daughters were contemplating the idea, was appalled by the seemingly careless defacing of youthful dermis, all in the name of fashion.

The first waves of this new tattoo era which lapped the shores of suburbia were not well received by my generation, nor were they understood. Truthfully, even those who got tattoos in those days did not truly come to grips with the true potential of tattooing as an art form, as an expression of personal commitment, passion and as a statement of one’s persona or a recounting of one’s history. The tattoo world that grew in those early years was a clutter of meaningless butterflies, inscrutable Asian lettering, faux gangsta posturing written in Gothic letters, barbed wire, and hilariously bogus tribal designs. To see a twenty-something college freshman in a wife-beater t-shirt with an arm wrapped in a Polynesian tribal tattoo of which he knew nothing (but all his buddies were getting them) made me angry. Worse were the thousands of suburban coed debutantes from Mississauga to Shaughnessy sporting cute little dragonflies, flowers, rainbows and bluebirds. I prayed the craze would go the way of disco before my daughters left home. But it did not.

What began to happen was that the plethora of tattooing going on led to better and better tattoo artists, better and safer parlours, and best of all, a greater generational understanding of the artistic and commemorative potential of permanently inking your body. Tattoos are no longer something you and your buddies do when you are drunk in Manila. They have become choices. You make appointments with artists with great reputations. You view their portfolios. No longer selecting from a visual menu posted on the walls or in laminated books, you bring sketches and ideas and you discuss them with “your” tattoo artist, much the way you would meet with your interior decorator or architect. Between the two of you, you come up with a design on paper and book successive appointments to begin and finish the execution. Many have a relationship with their tattoo artist similar to the one that they have with their hairdresser.

Some people who commissioned artists to “paint” on their bodies began to think not of themselves as tattooed, but more as “collectors” of art and sponsors of great artists—modern day Medici if you will, funding and encouraging artists, fostering and inspiring the renaissance of body artists. Their bodies, over a lifetime, become a minor art gallery, showing a form of art long reviled by traditional artists. Like any art form, there are the good and the bad, but when it’s good, it is indeed impressive. I have grown to embrace tattooing as a viable form of expression, as permanent as it is. I say this with the full knowledge that I would never do this to myself nor am I entirely happy that my daughter did it. But I love her and am satisfied that she thought it through and chose to connect her tattoo with a part of her that is important—her family.

True, the aviation tattoo art niche is decidedly illustrative in character, as opposed to painterly or expressive, but if you visit anyone of the websites for tattoo studios and parlours mentioned in this story, you will see works of exceptional creativity, expression, and complexity.

Over the past five years, three things have happened to change my mind. First, my daughter got her first tattoo—a simple line drawing of a Supermarine Spitfire in plan view on her lower back. She did this to commemorate her grandfather’s RCAF wartime service as a BCATP instructor and Photo Reconnaissance Spitfire pilot as well as her dad’s passion for all aspects of aviation. She would go on to add a Corsair, a Harvard and a Mosquito. Secondly, while researching the web nearly every day, I began to come across some outstanding airplane and aviation tattoos, beautifully crafted by talented artists. Despite my dislike of tattooing as I had known it, I began to grudgingly appreciate the good stuff. Thirdly, I came across Ryan Keough’s website called Tattoos in Flight. Ryan, an avowed tattoo fan and an aviation historian of some repute (he is an Associate Editor with the Warbird Information Exchange and the Warbird Resource Group) had been seeing, long before me, the powerful growth in the niche art form of aviation-themed tattoos. It was a revelation.

Ryan’s Tattoos in Flight website can be described as what you get when you mate Ray Bradbury’s short story compilation The Illustrated Man with the novel Twelve O’Clock High and John Wayne’s film, Flying Tigers. It is filled with hundreds of images of aviation-themed tattoos combined with excellent and well written historic and social histories of the aircraft depicted. It is clear that Ryan is in love with aviation as much as he is with the art form that is high-end tattooing.

One thing I saw clearly during my research was that not all tattoos are well done or well advised. I saw lots of human wreckage and some pretty scary things, but I saw a lot of glorious things too. Oddly, I did not see many bad aviation tattoos.

What follows is a collection of just some of the tattoos that Ryan and I found on the internet, thanks to tattoo forums, tattoo portals and websites like flickr.com and, in Ryan’s case, from reaching out to the tattoo art community via Tattoos in Flight. Tattooing as an art form may not be for you. That’s OK. You may think this story has nothing to do with aviation. That’s where you would be wrong.

Aviation is more, so much more, than power settings, pilot reports, factory outputs, acronyms, performance statistics, aircraft markings, technical minutia and squadron movements. It is wrapped in passion, culture, sharing, boldness and family.

Related Stories

Click on image

One does not have to tattoo an image of an airplane on one’s body to qualify as having an aviation tattoo. If the concept of flight represents, for you, the notions of freedom, exhilaration, unbounded joy and release from the daily grind, then, in fact, you are an aviator, whether you own an airplane or have earned your wings of gold. Perhaps there is no purer display of the appreciation of all that flight can be than to tattoo the opening lines of the greatest poem ever written about flight—John Gillespie Magee’s High Flight, written in the winter of 1941 after flying a Spitfire at 30,000 feet. This young lady wears on her back these immortal words in memory of her deceased and missed father. The young woman explains, “My dad, who passed away six years ago, was an avid pilot. I grew up hanging around the airport and flying with him in our Cessna 310, a Diamond jet, and the B-25 Mitchell “Fairfax Ghost” (he once flew it with Travis Hoover* sitting in the co-pilot’s seat). He was a Quiet Birdman, and so the poem “High Flight” was read at his funeral. I remember him reading it to me when I was 4, and a framed copy of it was my last Father’s Day present to him. I chose to use only the first two lines to make it my own. I’m a classical flutist, and those words evoke the feeling I get any time I perform, but also the memory of the man who encouraged me to go for my dream.” Her tattoo in memory of her father was created by tattoo artist Jason Jones of Kaleidoscope Ink in Springfield, Missouri. (*editor note: Travis Hoover was one of the original crew members of the Doolittle Raid.)

Of all the tattoos about aviation, the ones that strike a resonant chord with me are those beautiful portraits of aviators that have passed away and are honoured by a family member or enthusiast with a black and grey tattoo. Usually a favourite vintage photo is used and, with a quality tattoo artist, the result is powerful, emotional and poignant. Here is a grouping of nine tattoos I found, that for this viewer, really nail it. They are (L-Right, Top): Rib Tattoo of Josh Duffy’s pilot grandfather by Mike DeVries of MD Tattoo Studio in Northridge, CA; Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin by Jason Butcher of Immortal Ink in South Woodham Ferrers, Essex, United Kingdom; WWII fighter pilot by Aaron Bell of Slave to the Needle in Seattle, WA; (L-Right, Middle): Soviet fighter pilot of WWII by Corey Miller of Six Feet Under Tattoo Parlor in Upland, CA; a portrait of Charles Lindbergh by Jason Riggs of Lazy Lightning Tattoos of Indianapolis, IN; an F-101 Voodoo pilot from the 81st Fighter Wing, stationed at RAF Bentwater by Christian Masot at Silk City Tattoo in Hawthorne, NJ; (L-Right, Bottom): Another tribute to the owner’s grandfather, this time by Russ Abbott of Ink & Dagger Tattoo Parlour of Decatur, GA; a portrait of a crop dusting pilot who was lost in an accident commissioned by his sister and done by Oak Adams of Painted Temple Tattoo and Art Gallery in Sugarhouse Utah; “Flaps” Fowler, Mustang pilot by Tiger Rose Tattoo and Piercing.

Whenever I see a three-dimensional cutaway drawing of a complex engine in a book or on a poster, I am always amazed by the artist/draftsman’s ability to think in such depth and complexity. As an artist myself, I think of how difficult it is to do such a thing and how easily it could all go south, causing the artist to start over. Then I think of doing the same thing on the inside of a man’s arm with its soft, giving compound curves and I offer up the highest of kudos to artist Brett J. Barr for this stunning piece. If you make a mistake here, there is no starting over. This tattoo exudes power, imbuing its owner with traits of strength and reliability. Brett Barr, clearly a gifted artist, also did the B-24 Liberator tattoo in the next photo. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Undoubtedly, tattoo artist Brett Barr is one of my favourite of all the wonderful artists I have seen doing research for this story. While both the engine cutaway and this Consolidated B-24J Liberator in flight over “undercast” are extremely detailed and beautifully crafted, his other work is dramatic and passionately stylistic. It must be extremely difficult to draw the soft, hazy and transparent blurs associated with spinning propellers, for many artists simply freeze the props in motion or handle them in a different way from the rest of the work. Here, with subtle low-light and highlight blends, Barr nails it down perfectly. Barr was working for Built 4 Speed Tattoo of Orlando, Florida when this work was completed. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Canadian tattoo artists prefer Canadian subjects like this colourful calf tattoo of a pair of Spitfires in flight over a field of poppies. If you can’t afford to buy your own Spitfire, you can at least have a permanent homage to the famous fighter tattooed on you! This work was completed by tattoo artist Derek Dufresne of Fleshworks Tattoos in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Spitfire tattoos are definitely harder to find on the web. Here we have a 127 Squadron Spitfire in D-Day stripes and a shark’s mouth done by Kasbah Tattoo Studio in Leicester, England. The details here are very accurate. I checked with the great website spitfires.ukf.net and determined that, indeed, Spitfire ML185 flew for 127 Squadron from May 1944 until July of 1944 when it went to 313 Czech Squadron and then on to 118 Squadron. Photo via BigTattooPlanet.com

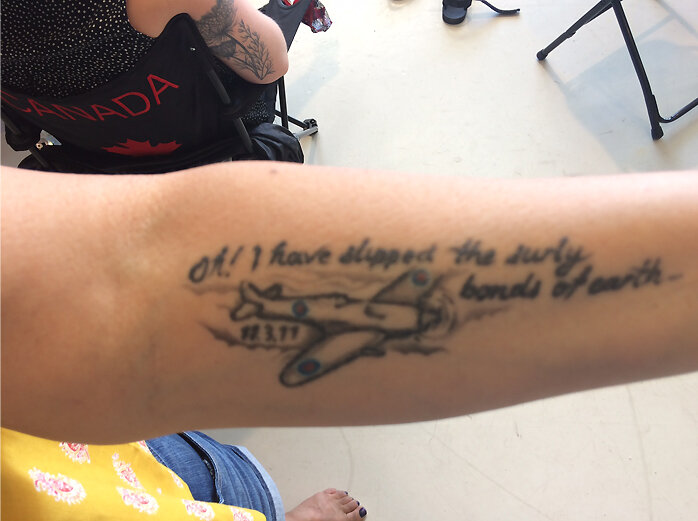

While in Calgary in July of 2017 for a memorial air show for our friend Bruce Evans, I had occasion to chat with his sister Donna who sported a Spitfire tattoo and the first line of the poem High Flight—first placed there to honour their father, a lifelong aviation man. But a year before, on 17 July 2016, Bruce was killed while performing low-level aerobatics at the Cold Lake Air Show. Now the tattoo reminds the lovely Donna of both of them. Photo: Dave O’Malley

The best Spitfire tattoo I came across was this fabulous arm sleeve of two Spitfire Mark Vs (one large glycol radiator on the starboard wing and a small oil heat exchanger on the port) overflying a gorgeous British-style locomotive belching vast quantities of smoke and steam. It was designed by Otto-Aspirin Tattoos

A well executed tattoo of an RAF 58 Squadron Spitfire by Gonzalo at Taste the Rain Tattoo Studio. Photo via CheckOutMyInk.com

Derek Rust took this photo of his friend Rachelle, an aeronautical engineering student at the Ohio State University who was recently apprenticing at Boeing. She sports a beautiful, yet somewhat ominous, black and grey tattoo of a B-2 “Spirit” bomber on her right shoulder blade. Photo: Derek Rust

When Chelsea Hicks had this simple solid black image of a delicate monoplane tattooed on her shoulder, she had a compelling desire to do so. Chelsea explains, “This is a tattoo of the Blériot XI monoplane designed by French aviator and inventor Louis Blériot. Despite crashing his other model and badly burning his foot from a gasoline leak, Blériot remained determined to win the “Daily Mail’s” prize for the first successful crossing of the English Channel by plane. On July 25th 1909, after his two competitors had failed to succeed, Blériot took to the air from France and though a developing storm took him slightly off course and essentially blinded him from all that surrounded him, Blériot landed 37 minutes later on the British Coast. After completing the first successful crossing of the English Channel, Blériot had this to say, “for more than 10 minutes I was alone, isolated, lost in the midst of the immense sea, and I did not see anything on the horizon or a single ship”. This story had me enamored from my first encounter with it and for me this tattoo is an inspiration and reminder to be bold and brave, to continue propelling myself forward as a traveler and to never stop getting lost amidst the sea”. Photo: Chelsea Hicks

“Mustang—Cadillac of the Skies”, as the young Jim Graham says in the movie Empire of the Sun. This tattoo wearer learned how to fly at a back-patio flight school at the famous Van Nuys Airport in the Los Angeles area. The airport, featured in the 2005 documentary One Six Right, remains the World’s busiest General Aviation airport and has been home to many aircraft, including many P-51 Mustangs, over its history. During his training, our subject became friends with a fellow student pilot at the club, a Russian native who also happened to be a talented tattoo artist from Hollywood. His name is Konstantin Nossatchev. Since both were aviation fans, they talked about a deal to create an elaborate piece for the subject. As both loved the P-51 Mustang, the design was a perfect fit. Also incorporated into the design was the tail-number of the Cessna 172 he first soloed in, his lucky number as the squadron number on the fuselage and his last name as the nose art. The entire piece took Konstantin three sessions to complete. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

One of the things that makes tattoos featuring aircraft so challenging is the amount of detail that many aircraft require to look accurate. As a result, airplane tattoos generally work better when they cover a larger part of the body rather than small areas… backs and torsos seem to work especially well. This tattoo of a North American P-51 Mustang ripping dramatically out from a man’s back is a perfect example of the artist and wearer giving a tattoo plenty of room to look its best! The proportions of the P-51 are right on the money! He got the tattoo in honour of his grandfather who flew as a crew member aboard a B-29 Superfortress during the war. The “S2” on the nose of the P-51 symbolizes both he and his wife as their initials both begin with the letter “S.” The tattoo was created by an artist named simply C.W. of Royal Street Tattoo located in Mobile, Alabama. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A dramatic black and grey arm tattoo of a P-51 Mustang shooting down a Luftwaffe adversary with guns blazing away and empty machine gun cartridges tumbling from the ejectors. Artist David Newman-Stump of Skeleton Crew Tattoo in Columbus, Indiana created this beautifully shaded and highlighted image—in fact his first aviation themed tattoo. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

This British man had a leg wrapped in a montage honouring the legendary P-51 Mustang—a most favourite of subjects for aviation tattoo artists. Though almost always associated with the United States Army Air Corps of the Second World War, the Mustang is in fact a design response to an RAF design specification and request for proposal. This colourful and glorious leg tattoo montage of USAAC P-51 Mustangs was created by Oliver Jerrold, a tattoo artist at Hope and Glory Tattoo in Swaffham, Norfolk, England. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A colourful back piece of a P-51D Mustang covers this man from shoulder to shoulder. “Babydoll” was created by tattoo artist Carlos Rubio of Club Tattoo in Mesa, Arizona. The flatness of the upper shoulders and back makes it easier to appreciate the straight lines and edges of the wings of the P-51. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A crowded and busy scene of a European Theatre dogfight with North American P-51 Mustangs and German aircraft loosely based on the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and the Focke-Wulf Fw 190—with propellers thrashing, bullets flying and aircraft zooming everywhere. This forearm sleeve, dramatically tattooed in black and gray, was created by Jeremiah Barba of Outerlimits Tattoo in Long Beach, CA. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A P-51 Mustang leg sleeve viewed 90º to horizontal. This is one of my favourite tattoos I found during my search—a North American P-51 Mustang with a Vargas-style pin-up nose art figure. This magnificent masterpiece was created by tattoo artist extraordinaire Kevin Patrick of State of Art Tattoo at the Arizona Tattoo Expo 2012. The image features exquisite weathering and riveting on the metal skin and makes spectacular use of the leg shape of “collector” Matthew Nelson of Buckeye, Arizona. Tattooing is indeed an art form whether you are too old to accept it or not. The tattooing community knows it and folks who have tattoos on their bodies think of themselves as collectors in the same manner as a wealthy art collector. Photo: Kevin Patrick

Tattoos have been used to demonstrate intense loyalty to certain quality brands and manufacturers for years. Companies like Harley-Davidson, John Deere, and Playboy have reaped the benefits of enthusiastic fans who forever pay homage on their skin. This tattoo, on the inner and rather large bicep of this man, was created by artist Lelo at Gatto Matto Tattoo Studio in Campinas–São Paulo, Brazil. The wearer had been waiting to get the tattoo for 15 years, and finally made his dream come true at the age of 30. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Speaking of loyalty to a brand, our own volunteer extraordinaire, Stéphane Ouellet, who had our logo tattooed on his calf. Stéphane expresses his loyalty in other ways too, on hand at all times to help. It was Stéphane’s tattoo that first got me thinking that this story should be done. Photo: Josée Lavictoire

As the last three images have shown us, not all aviation tattoos have aircraft in them. Jerry Fielden, author of 438 Squadron RCAF’s squadron history called Le 438e Escadron Tactique d’hélicoptères, 1934-2009, wears this Second World War 438 Squadron Wildcat cartoon, drawn originally by artists at Disney. Photo via Jerry Fielden

It’s a common practice for those in the armed forces to permanently commemorate their service in the form of a tattoo. Just as sailors collected tattoos for centuries on their visits to exotic ports of call to remember their travels, today’s soldiers, sailors, and airmen (and women) do the same to remember that part of their life which helped shape their adulthood. This shoulder tattoo, created in black and gray shading, was created by artist Erik Payne of Inkvision Tattoo Studio in Boise, Idaho. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

This colorful tattoo of the curious choice of an Ayres S2R-T “Thrush” crop duster as a subject with the inscription under it translated from Portuguese as “Trust in God” was created by artist Mauricio Huber of Dermografite, located in the coastal city of Balneário Camboriú in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A powerful image of a man in Borneo who left to go to work in Seria (Brunei) in 1974, and he commemorated his first trip ever on an airplane (a Malaysian Airline System flight from Kuching to Miri) with this tattoo. This crude, yet powerful, image is reminiscent of the “pick and poke” tattoos of prison inmates from Brazil to Los Angeles. Homemade tattoos when done with commitment as this one is have a singular menace to them yet clearly this is only a celebration of an important event. Photo: D. Lumenta at Flickr.com

This tattoo of a DC-10 was created by artist Eddie at Skin Factory Tattoo in Las Vegas, Nevada for a client who wished to commemorate his father’s service with Northwest Airlines and his inspirational fatherhood. As Eddie’s client said, “My Father, a 39-year Northwest Airlines Captain, passed away after a four and half year battle with cancer. He has been my greatest inspiration to follow my dreams and take to the sky to leave my own contrails. The DC-10 was his favourite aircraft and I could think of no better way to represent that than on my chest!” No better reason for a tattoo. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

The Il-2 Shturmovik was a Soviet ground attack aircraft of the Second World War built in mind-boggling numbers—more than 36,000 in all. While there is only one recently finished flying example in the world today, its story remains iconic of the determination and sacrifices of the Great Patriotic War. Retreating German Wermacht and SS troops grew to fear this simple killing machine. This tattoo was created by artist Kris Witakaye of The Inkwell in Southampton, Pennsylvania. Its wearer, an Airman First Class with the USAF working as an Air Traffic Control specialist, chose the tattoo after finding the story behind the Il-2 fascinating—an aircraft feared by the most feared army was “too much to pass up” according to him! Photo via Tattoos in Flight

The Curtiss P-40’s aggressive looking nose with chin intake makes it one of the most popular subjects for aircraft tattoos. Created by tattoo artist Phil Garcia at Ink Philler Studios in Port Hueneme, California, just north of Los Angeles in Ventura County, this P-40 Warhawk tattoo, according to Tattoos in Flight, is “a clear example of how far tattooing as an art form has come in modern days. The vibrancy of the piece, the level of detail, and the amazing use of layered and blended colors and negative space to define the tattoo make this piece stand out”. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A Flying Tigers P-40 Warhawk with shark mouth and Nationalist Chinese markings blazes away at a Japanese adversary, after dispatching another Mitsubishi Zero fighter. This tattoo, by Chris Stans of Kapala Tattoo in Winnipeg, Manitoba was created for a client in mid-2008. She wanted the classic P-40 and the quote “Hold Your Ground” was important to her. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

To get the “fighting spirit” essence of a Second World War fighter, it is not necessary to include the entire aircraft. Here the artist has combined the classic shark-mouthed P-40 Warhawk image with hot rod custom flames for a super aggressive look on this man’s forearm. It looks like a punch from this dude would really hurt. Photo courtesy of www.tattoojoy.com

This inner arm tattoo shows that famous AVG P-40 Warhawk snarl to great effect. Similar in concept to the one above, it was tattooed by Hawk Chait.

This great half sleeve featuring two B-24 Liberators working their way through heavy flak, while dropping their payloads, was created by tattoo artist Travis Grabhorn of Patriot Tattoo located in Spring Valley, California. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

There are many reasons for tattooing an image of an aircraft on your body. One could simply be a lover of vintage aircraft or history like me or perhaps one only thinks it looks cool. But many of the tattoos featuring Second World War fighters and bombers are created and the pain endured to honour the memory of a father or most likely a grandfather who flew or was aircrew during the war. Because of its iconic status, the Chance Vought F4-U Corsair remains a common yet powerful theme in aviation tattoos and this memorial tattoo pictured here is no exception. This fantastic black and gray version, tattooed by Phil Young of Hope Gallery Tattoo in New Haven, Connecticut, perfectly depicts the famous inverted gull-wing bird with all its dark reflections. Ironically, the Corsair is the “official state aircraft” of Connecticut due to the fact that many were manufactured in Stratford during the war. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

The simple ethereal light in this massive tattoo of a B-24 Liberator makes it one of my favourites. This particular tattoo, of a D-Model “Lib” (with the greenhouse style nose), was created by artist Hector Cedillo of Skin Graff Tattoo in Worcester, Massachusetts. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Jonny Breeze created this tribute tattoo for a client whose grandfather was a gunner on Lancasters during the war. A little sleuthing paid off with some good information about this aircraft and its fate. I think it important to know the details as this lends power and meaning to the tattoo. I am not sure what the letter “G” stands for in this inscription, as NE141 had aircraft code AR-P, not AR-G. 460 Squadron Lancaster “G” is, however, the most famous Lanc of the squadron and is still in existence and on display in Australia. 460 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force Avro Lancaster NE141 was shot down on the 21st of November 1944 during a night raid to Aschaffenburg, Germany. 460 was a hard bitten Bomber Command Squadron and lost 200 aircraft and 1018 airmen over the course of the war, out of a total of 2730 men who served with the Squadron. A further 200 or so crew were captured as prisoners of war. Photo and tattoo: Jonny Breeze Lancaster NE 141 took off from RAF Binbrook at 1537 hours on 21 November to bomb Aschaffenburg, Germany. Bomb load 1 x 4000lb and 16 x 500lb bombs. Nothing was heard from the aircraft after takeoff and it did not return to base. Twenty three aircraft from the squadron took part in the raid and two of these, including NE141, failed to return. Following postwar enquiries it was established that the aircraft crashed on 21 November at Damm, a suburb of Aschaffenburg. All the crew were killed. The names of PO McMaster, FO Pettiford and FO Stewart are recorded on the Memorial to the Missing, Runnymede, Surrey, UK. Flt Sgt’s Herbertson, Jones and Chandler are buried at Durnbach War Cemetery, Germany.

Crew: PO McMaster, R F Captain (Pilot) / FO Pettiford, F J (Navigator) / FO Stewart, K R (Bomb Aimer) / Flt Sgt Herbertson, W (Wireless Operator Air) / Sgt Day, H (Flight Engineer) / Flt Sgt Jones, M A (Mid Upper Gunner) / Flt Sgt Chandler, R S (Rear Gunner)

Despite being done in classic black and grey, this tattoo seems to leak colour. The attention to detail and craftsmanship in this piece is simply breathtaking—especially so when you realize the extreme curvature of the man’s shoulder. One of the best works I have run into, this RAF B-25 Mitchell was done by Mark Lazio of Ground Zero Tattoo in Riverside, CA. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A stunningly powerful, massive and detailed image of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress “Yankee Doodle” tattooed in a massive sweep across this young man’s rather buff canvass. Part of its power lies in the fact that there are no other tattoos surrounding it. This is a spectacular piece which, if the young lad stays in shape, will continue to impress everyone. Perhaps, later in life when he is carrying a beer and wings belly and a coat of mid-life hair, this will lose some of its lustre. The artist Hayley Lakeman from North Carolina works at Fu’s Custom Tattoo in Charlotte. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Every tattoo artist, like his or her oil painting, watercolouring or bronze sculpting colleagues, has a unique style, a sense of form and palette. Artist Matt Maguire of Witch City Ink in Salem, Massachusetts has a bright, chalky and illustrative style reminiscent of war bond and recruiting posters of the Second World War. Here, the Boeing B-17G Flying Fortresses depicted carry the markings of the RAF Bassingbourn-based 91st Bomb Group, 323rd Squadron. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

One of my favourite types of tattoo is the simple heavy black ink silhouette like this top-lit Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress done in the style of legendary British graffiti artist Banksy. This one was created by Simone Lubrani of New York’s Rising Dragon Tattoos studio. Photo: Simone Lubrani

Colourful aerial combat in the Pacific theatre combined with an image of a sultry blonde speaks volumes about the testosterone-charged world of aerial combat in the biggest war ever fought. Illustrated here is a very colourful collage of a Second World War dogfight over the Pacific between two US Navy Grumman F4F Wildcats and two Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters. The inspiration for many pieces of “nose art” on bombers and fighters, the pin-up and the magazines they came from were as much a part of a serviceman’s boot locker as… his boots! The tattoo was created by Lea Vendetta of Dave and Lea Tattoo. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Mez Love of San Francisco’s Tattoo Boogaloo created this Second World War and Vietnam War dual tribute entitled “Heroes” for a client who wanted to honour his aviator grandfather and father—a Lockheed P-38 Lightning and a Huey gunship. The red hue in this and other images of tattoos in this story indicates that the tattoo has been recently worked on. Photo via Mez Love

This beautiful back piece tattoo featuring a pair of olive-drab USAAF P-38s in formation is done on a young woman’s back as a tribute to her grandfather. The work was done by Jeff Croci at Seventh Son Tattoo in San Francisco, CA.

I just love the rendering of sparkling sunlight on this tattoo of Baron Manfred von Richthofen’s Fokker Dr.1 Dreidecker triplane. The Red Baron lives on today as an icon of icy skill and colourful dash. This work was created by tattoo artist Chris Chubbuck of Venom Ink Tattoo in Sanford, Maine. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

“Beware the Hun in the sun” went the old fighter pilot’s caution from the First World War. Here, in this simple yet evocative black and white tattoo by Christen Shaw, a British pursuit plane tumbles down in flames while the Red Baron in his Fokker triplane looks for his next victim. Photo: Christen Shaw

A super clean, perfectly rendered tattoo of a MiG-29 Fulcrum by Ukrainian tattoo artist Denis Sivak shows the fighter appearing to execute the famous “cobra” manœuvre. The Fulcrum is powered by two massive Klimov engines, each putting out more than 18,000 pounds of thrust—very evident in this view. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Now that the Top Gun superstar F-14 Tomcat has gone the way of the dodo, the only way to be reminded of the mighty Grumman fighters is to see them preserved in museums, immortalized in history books or, as in this case, as a permanent tribute tattooed within easy sight. This highly-detailed inner arm tattoo is the work of legendary artist Shotsie Gorman, who now applies his trade from the West Coast near Sonoma, California. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

While the F-14 Tomcat may be history, its Air Force contemporary, the F-16 Fighting Falcon, is alive and well and flown by several air forces around the world. This highly detailed and perfectly drafted F-16 tattoo was created by artist Craig Beasley. We can make out the golden end-of-day light on the fuel tanks and fuselage. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Scantily clad bombshells and Navy Corsairs combine to create a colourful tattoo with depth and loads of testosterone. Cecil Porter, the artist, works from a private studio at Under The Gun Tattoo in Hollywood. This particular tattoo won Best Tattoo of the Day at the Body Art Expo in Pomona, CA in January 2009.

Aviation tattoos, a growing genre in the ink world, are truly universal. Here we see a young Ukrainian man sporting a well drawn image of an Antonov An-2 “Annie”, a sturdy and reliable postwar transport, now operating worldwide. Perhaps its characteristics of reliability, simplicity and strength are admired by this young man. The work was done by Ukrainian tattoo artist Denis Sivak. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

I have made no bones about the fact that the Martin B-26 Marauder, built near Baltimore, Maryland during the war, is one of my favourite aircraft designs of the Second World War. Its broad shouldered, somewhat overpowered look makes it a true muscle car of medium bombers. And like the thundering muscle cars of the 1960s and 70s, it can be a lot to handle for an inexperienced driver. These aircraft developed a well-earned reputation for separating the men from the boys, earning for themselves some pretty harsh monikers: the Widow Maker, the Baltimore Whore and One-a-Day-in-Tampa-Bay. This detailed B-26 Marauder tattoo was created by tattoo artist Carlos Rubio, owner of Disciple Tattoo in Chandler, Arizona. Not only is the Marauder one of my favourite aircraft, this work by Rubio is also one of my favourites, with its somber light, chalky camo paint and nicely rendered paneling. It is designed to be the centrepiece of a B-26 leg “sleeve” tattoo. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Though the top three aircraft preferred by collectors of tattoos are surely the P-51 Mustang, the P-40 Warhawk/Kittyhawk, and the B-17 Flying Fortress, this black and grey B-26 Marauder makes for a very individual choice. The nearly photographic work was completed by artist Pows One at Starlight Tattoo in New Jersey.

The Vought F4U Corsair is one of the most frequently tattooed warbirds out there, but seeing an example painted in the markings of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm is rare indeed. This tattoo was accomplished by Vincent Meyer for a client in Salmon Arm, British Columbia. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

A pair of identical USN Corsairs adorn this person’s shoulder blades. Here we see the Corsair on her right shoulder. Tattoo was by Christel Perkins, Robot Tattoos

While the image of that first flight of the Wright Brothers at Kill Devil Hills is forever tattooed in the memories of any aviation-loving person, it is certainly reinforcement when one has it tattooed on his inner arm forever. This seems a tribute to the boundless possibilities of invention and creativity. In honour of this historic aircraft and historic flight, this beautiful black and gray inner arm tattoo was created by tattoo artist Hoffa at Ascension Tattoo in Orlando, Florida. We wonder if it is a coincidence that Hoffa is also from Dayton, Ohio, the hometown of Orville and Wilbur. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

While the Mustangs and Warhawks dominate the dermis of aviation fans, less common types are still to be found. Here a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt overflies a mountain range.

Nothing goes together much better than fighter aircraft and bombshell pin-up girls. Tattoo artist Johnny Gage created this whimsical interpretation of a scantily-clad aviatrix in red, riding astride the turtle deck of a shark-mouthed Hawker Hurricane... obviously in a state of ecstasy. Johnny works at The Tattoo Studio, Crayford, Kent. Photo and tattoo: Johnny Gage

Near where I work is a place called The House of Barons where a man, a real man, can get a shave and a haircut while watching war movies, westerns and old episodes of Dogfights. My friend Devon “Red” Hayter, a Harley-riding, dog-lovin’, remarkably tattooed, warbird savvy barber, trained in the old ways, will give you a close shave and a half hour’s worth of Corsair facts. Trained at our Corsair ground school, Devon can expound on hydraulic systems and wing folding as well as body piercing and Harley maintenance. Devon spotted this tattoo on a client and sent it our way. On the inner arm of Greg Diamond, this skull and Spit was created by Jimmy at Lotus Land Tattoos in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Dustoff in the Dermis. Even though the end of the Vietnam War was nearly four decades ago, when many people think of the war, one of the first images that comes to mind is that of the Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter, more commonly known as the “Huey”. Its widespread use throughout the war by every branch of the U.S. military solidified it as a symbol of military service in Vietnam and, as a result, many tattoo tributes for Vietnam veterans feature the Huey such as this half-sleeve upper arm piece. This tattoo depicts a scene that perfectly illustrates the two most common uses of the UH-1 Huey: large-scale troop insertion into a combat landing zone (or “LZ”) on the outer arm (left side of image) and a “Dustoff” casualty extraction by UH-1 medivac on the inner arm (right side of image). Also included in the tattooed scene is the ribbon of the Vietnam Service Medal over the crossed rifles of the Infantry Branch of the U.S. Army at the top and the insignia of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) under it. The tattoo was created in honour of the father of the wearer, who is an Army veteran of the Vietnam War and served his tour of duty from 1966 through 1967. The tattoo was completed in May 2010 and she proudly showed her father the completed tattoo on Memorial Day. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Some more complex tattoos are in fact complete tableaux depicting aerial battles and grouping elements into a thematic montage. This beautiful full arm sleeve tattoo, created for the 100th anniversary of Naval Aviation in 2011, depicts some of the most famous American naval aircraft of the Second World War including (from the wrist upwards), the Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina Patrol Bomber, the Grumman TBF (TBM) Avenger torpedo bomber, the Grumman F6F Hellcat carrier-based fighter aircraft, the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bomber, and the Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber at the very top. The artist, Matt Geiogamah, is well known for his realistic colour tattoo work, unique and vibrant colours and fantastic composition… attributes perfectly seen in this piece. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Not forgotten. The CF-105 Avro Arrow is a legendary interceptor design that captured Canadian imaginations during the cold war in the same way that the Spitfire spoke to the British a decade and a half before. The government cancelled the massively expensive project for the RCAF with only a half dozen or so prototypes built and in so doing set back the Canadian aerospace industry by years. Canadians never forgot the damage to their national esteem, eventually creating a mythic personality with overblown potential for the big, beautiful delta winged fighter. Still, probably more so than if it had survived, it has become a national icon and symbol of dreams almost achieved. This tattoo by Canadian tattoo artist Derek Dufresne of Fleshworks Tattoo Studio in Victoria, British Columbia pays tribute to the aircraft legend that pains many today... even this young man who no doubt was born a quarter century after the cancellation of the program. Photo via Tattoos in Flight

Airplane tattoos don’t always have to be about heavy bombers, flame covered shark-mouthed fighters or mayhem, they can celebrate the joy of the ordinary aircraft and the achievement of becoming a pilot. Tattoo by Dave Kruseman of Forever Yours Tattoo Gallery in Douglasville, Georgia

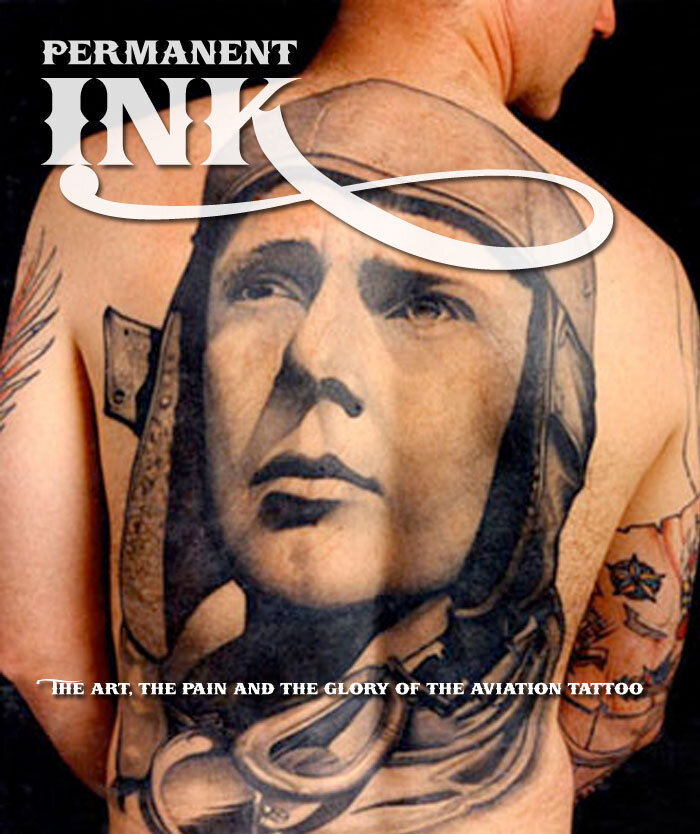

Finally, we end on the image we started this story with, perhaps the most striking of all the tattoos in this genre. This, in many ways, shows us just how far tattooing has come. One can no longer just say this is a tattoo, but rather, this is an ink portrait on a man’s back, no different than an ink portrait on canvas or art board. This tattoo of aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh by famed tattoo artist Shotsie Gorman was featured in countless magazines and exhibitions after it was completed. We’ve found a video clip where Gorman speaks about the tattoo and the challenges it presented—click here to view it. Shotsie Gorman is in Sedona, Arizona with Shotsies Soul Signing. Photo: Bill DeMichele of Proteus Press via Tattoos in Flight

Post Script

A year after this story was published a young French warbird enthusiast, Gauthier Boucher, came upon this story and was inspired to go ahead and create a tattoo of a P-51D Mustang. The design is pure Mustang and beautifully crafted. Clearly he chose his artist with great care. Here is his letter.

Dave

Not a long time ago, I was considering to be inked on the forearm with a warbird, so I searched the web for inspiration. But aviation tattoos are not really easy to find, and for most of them, not worth a find, for I’m really demanding on shapes, and realism. As you know, planes are all angles and lines, that are unfortunately hard to reproduce on something as soft and elastic as the human skin…

And then I found your article. Really interesting, and in a way, inspiring. The gathering of tattoos, the different styles you showed in it allowed me to think about what I was not looking for and actually, looking for. The black and white silhouette of the B17 struck me: such minimalism capable nevertheless to make people think immediately: “this is a vintage bomber”. No need of much details, rivets, joints, even turrets. I found it brilliant!

Well, thanks to this find of yours, I pinned down what I wanted to ink on my forearm, and went looking the web for “warbird silhouette” and such things. It came out with a project, and then, the inking.

So here is my “little friend”, a P-51D from WW2 (not a Canadian one, sorry!)

For this fellow is now part of me until the day I die, I felt like I was going to the web, find your article back and write you a little something to thank you for your help.

Kind regards,

Gauthier B.