BLAST FROM THE PAST

Painting by Piotr Forkasiewicz

All day long on the first of January 1944, the weather at RAF Gransden Lodge and throughout most of Cambridgeshire was grey and cloudy with typical English mists drifting across the airfield. The winds were moderate and out of the west. The Lancaster bomber crews of No. 405 Pathfinder Squadron stationed at Gransden Lodge were stood down for the day, some recouping from New Year’s Eve revelry. At a briefing they learned that there would be an operation that night, but take-offs wouldn’t begin until after midnight. The target was Berlin. They had several hours to endure the stress of inactivity, but once they had strapped in, they would settle down. They were Pathfinders after all—elite bomber crews, the best of the best, who would lead the Bomber Stream to the target and mark it by accurate bombing, the kind of accuracy the Pathfinders were trained for and capable of.

Flying Officer Tom Donnelly and his crew were ready for the task. Donnelly himself was a veteran on his second tour of operations. Surviving one tour was an accomplishment, beating odds that were well stacked against making it home alive. His bomb aimer, Sergeant William L.T. Clark, was feeling good. He had spent the previous evening in the company of his brother Jack who was also in the RCAF, reminiscing about life back in Vancouver and getting home after the war. He was happy to be in Donnelly’s crew—the skipper was experienced and fun to be around. He wore the ribbon of the Distinguished Flying Medal on his battle dress jacket and the winged “O” pin of an airman who had completed a full tour already. It gave Clark a sense of confidence seeing that ribbon, but looking at that pin, he had to wonder when Donnelly’s luck would run out. Luck was such a huge part of it.

Always, when the target was Berlin, the boys got quiet and moody. Stress was hard to hide. Berlin was a 1,900 kilometre round trip in the proximity of hundreds of other bombers in total darkness, across flak concentrations and the deadly hunting grounds of Luftwaffe night fighters. It was reasonable for man to be worried.

At around midnight the signal flare went up and the twelve Lancasters of 405 Squadron RCAF moved out to the runway in the dark. Donnelly and his boys were in Lancaster LQ-K, RAF serial number JB280. The Lancaster had survived three and a half months of operations with 405 since its delivery date on the 16th of September 1943, a week after it rolled out of the factory. In her belly, LQ-K carried a relatively light load, for they were flying a long way tonight—four 1,000 lb. bombs and one 4,000 lb. bomb called a “cookie.” This type of ordnance was designed for the destruction of industrial centres. At 23 minutes past midnight, in the very early hours of the second day of 1944, Donnelly, Bomb Aimer William Clark, Navigator Jerry Salaba, Flight Engineer Leslie Miller, Radio Operator Brian West, and Air Gunners Ron Zimmer and Ron Watts lifted off the active runway in darkness and radio silence, climbing and circling until the squadron was formed and headed to join the Bomber Stream where a total of 421 Lancasters coming from all over southern England would join together in the dark of night and head toward Berlin—1,684 Merlin engines delivering the whirlwind of vengeance, almost 3,000 young men huddled in darkness, cold and menace, surrounded by fear, powered by courage and love of their brothers. Though there were thousands of men up there in the night sky, each man felt alone—dry mouth, high pitched voice, darting eyes, forced jocularity.

The 405 Pathfinder Squadron operations and planning room at RAF Gransden Lodge, about 16 kilometres west of Cambridge, England. In this busy and smoke-filled room, missions were planned down to the smallest detail, taking into account all variables such as fuel, daily signals, meteorology, intelligence, German defences and bomb fusing times. After planning, the squadron assembled for a briefing before being driven to their aircraft. Photo: RCAF

Somewhere near the coast of England they joined the stream and headed across the North Sea. With them was a small group of fifteen Bomber Command Mosquitos that would attempt a diversionary attack on Hamburg. It didn’t work. The night fighters’ dispatchers were not fooled this night.

As Donnelly and his crew settled down over the North Sea for the long flight across Holland and Germany, night fighters were rising to meet the stream. These highly experienced Luftwaffe crews flying night fighting variants of the Junkers Ju 88 and Messerschmitt Bf 110 were the true scourge of Bomber Command. Unlike searchlights and flak, which to some extent could be avoided, night fighters were unseen, vicious and above all, unpredictable. The entire crew relied on the sharp eyes and night vision of their two air gunners—Watts in the rear turret and Zimmer in the top turret. Watts was 33 years old, young by today’s standards, but ancient in a squadron of teenage boys and twenty somethings. Zimmer had just turned 20 years olf.

As they crossed the coast of Holland, they avoided the heaviest concentrations of flak and droned on through the night towards their destiny—alone among 420 other crews. Around 2 AM, Salaba would have called Donnelly on the intercom to let him know the Dutch-German border was just ahead. In a few minutes they would be over the homeland of the enemy. Here they would face the most determined of defences.

About the same time as Salaba updated his skipper, Luftwaffe ground radars were vectoring a Messerschmitt Bf 110 night fighter into the Bomber Stream close to LQ-K. It was pitch dark at 20,000 feet, but a trained night fighter pilot could spot the exhaust flames and sullen dark shapes against a murky black sky. The pilot of the all-black Messerschmitt was Leutnant Friedrich Potthast, known as “Fritz” to his pals. With him in the cockpit were two others—a rear gunner and a radio operator in contact with the ground. Potthast had been a fighter pilot since near the beginning of the war, but he had only three other kills to show for all that fighting—two Blenheims on 19 August 1941 in particular. But tonight, he would begin a streak that would net him 8 more night kills before his death five months later. Night fighting was proving to be his forté.

Luftwaffe ground crew refuel a Messerschmitt Bf 110 night fighter of the famous Nachtjagdgeschwader 1. Of all the night fighter squadrons in the Luftwaffe, NJG-1 was the most successful, shooting down an astonishing 2,311 enemy aircraft. The unit paid a heavy price for this reputation with 676 aircrew killed in action. The high number of victories by NJG-1 was testimony to the terrible dangers faced by Bomber Command aircrews every night. The unit’s emblem was a diving white falcon with a red lightning bolt striking a map of Great Britain. The pilot of the night fighter that shot down JB280 was Leutnant Friedrich “Fritz” Potthast, an ace with 11 kills to his name (8 at night and 3 by day) when he was shot down nearly five months later on the night of 21–22 May 1944 near Sourbrodt in eastern Belgium. Lancaster JB280 was his fourth kill. Night fighter Bf 110s had a crew of three—pilot, rear gunner and radio (radar) operator. It is not known who was with him the night he shot down the Donnelly crew, but on the May night he died, his two crew members were Feldwebel (Sergeant) Albert Kunz and Obergefreiter (Aircraftman) Hans Lautenbacher. Photo via Bundesarchiv

Related Stories

Click on image

We will never know the full details of what happened over the next ten minutes in the night sky near the Dutch-German border, but at approximately 2:10 AM, the remains of Lancaster JB280 and its crew came shrieking, flaming and tumbling out of the night sky near the small town of Nieuw-Schoonebeek, slamming into the ground not 200 metres from the German border. The wreckage contained the bomb load of Donnelly’s JB280, but likely centrifugal forces had sent the five bombs off on their own trajectories [photos of the fuselage section on the ground do not show the kind of damage one would expect if the bombs exploded while still attached.]

The ensuing explosion of the bomb load caused considerable damage to nearby homes, blowing out windows for some distance and damaging roofs. The farmhouse of a Mr. J.G. Lambers was heavily damaged as were some of his outlying structures. One of his horses was cut down and, according to reports, he lost a dozen chickens.

One can imagine the spectacular and life-changing drama of a four-engine bomber falling in flames from the night sky—the shrieking wind, the rending of metal, the ultimate devastating impact with the ground. Today, such a powerful scene would be world news, but on the night of 1–2 January, it happened 28 times along the flight path of the Bomber Stream in and out of Berlin. The 28 Lancasters held 196 young men. Night after night, month after month, year after year, metal and youth would be broken against the obdurate ground of Europe. While it became commonplace in a broad sense, it was nonetheless a traumatic event for local witnesses, causing in many cases injury and death, and in all cases powerful emotions and haunting memories for the rest of their lives.

Dutch citizens come by to look at the wrecked fuselage of Lancaster JB280 lying in a farm field near the town of Nieuw-Schoonebeek. The framework at the right of the fuselage is the floor above the bomb bay with doors gone. The faring around the hole in the centre of the fuselage section is for the H2S Radar, the antenna housing having been destroyed. These wrecks would soon be loaded on to trucks and driven away to be melted down for German production. Photo via drentheindeoorlog.nl

The same Lancaster JB280 fuselage section as above, but viewed from the other (top) side. We can clearly make out the letters LQ-K. The Fraser-Nash power-operated dorsal turret glazing framework lies crushed at centre. Photo via drentheindeoorlog.nl

As the wreckage of JB280 and her seven young crew members lay burning and smoking on Lambers’ farm, the Bomber Stream, heard but unseen in the night sky, continued it relentless and harrowing journey into the heart of Germany. Donnelly’s demise was possibly witnessed by others in the stream—tracers in the distance, flames blowtorching in an invisible hurricane, silent screams—but none could know who it was. Gunners and pilots of other Lancasters could only glance at the drama and perhaps inform their crews (There goes another—bloody hell!), but they had a job to do. If anything, the arcing smear of flame in the distant night sky that was once a Lancaster was a warning that wolves were in their midst. Men turned away from the death and concentrated on watching their own immediate sky. Terrible… but lucky us.

Of the night’s work by Bomber Command, the RCAF post war journal called The RCAF Overseas had this to say of the night: “January 1st, 1944, marked the opening of the second year of operations of the R.C.A.F. Bomber Group, a component of Bomber Command. The twelve months had seen a notable development in the operational efficiency of the squadrons so that with the opening days of the New Year, members of the Group could look forward in quiet confidence to a period of increasing responsibility. In the year to come, the Group, its growing pains past and forgotten, was to come into its own as one of the most efficient fighting units in all the United Nations Air Forces.

Our Lancasters, almost without exception, found complete cloud cover from base to target and back when they attacked Berlin on New Year’s night [actually they took off after midnight—on January 2nd]. For the most part they stooged along between cloud layers and as a result were little bothered by searchlights except when the clouds cleared momentarily to allow the Cologne-Kassel-Frankfurt band to break through. Night fighters were not particularly in evidence and flak was never troublesome, yet the raid was far from being an outstanding success.

The target area was completely covered, the tops of the clouds varying from 10 to 18,000, and many of our kites found a further heavy layer above that. Furthermore, the pathfinders were having an off night and their work was erratic and scattered. As a result, the host of bombers, averaging 12 per minute over the target, returned to their various bases with little concrete knowledge as to whether the hundreds of tons dropped had really achieved the desired result, but quite convinced in their own minds that the raid, considered as saturation bombing, had been largely abortive. Nevertheless, such a weight of bombs dropped on a city like Berlin must have done very considerable damage and the effort therefore was not entirely in vain. F/O T.H. Donnelly, D.F.M., on his second tour of operations, was lost on this raid with his crew, F/O A.J. Salaba, FS W.L.J. Clarke and Sgts. B.S.J. West, R.E. Watts, R. Zimmer and L.G.R. Miller.”

The pilot and aircraft commander of Lancaster JB280 was Flying Officer Thomas Henry Donnelly, DFM, MiD (J/17137), a highly experienced veteran Bomber Command pilot. He was on his second tour of operations, and judging from this photo, he was a charming and confident young officer. Donnelly was the 23-year old son of Thomas and Jessie Donnelly of Sprotbrough, Yorkshire. Thomas was born in Toronto, Ontario. Donnelly was awarded his Distinguished Flying Medal as a Flight Sergeant with 57 Squadron, RAF and was gazetted in August of 1942. The citation accompanying his DFM reads “Flt. Sgt. T.H. Donnelly, No. 57 Sqn.—As captain of aircraft Flt. Sgt. Donnelly has carried out many successful sorties over enemy and enemy occupied territory, including targets at Essen, Kiel, Cologne, Hamburg and Brest. Many of these bombing attacks have been carried out at below 10,000 feet and in adverse weather. He has often remained in the target area for long periods, making several runs over the target to ensure accuracy of his bombing. On several occasions Flt. Sgt. Donnelly’s aircraft has been damaged by enemy anti-aircraft fire, but he has at all times pressed home his attacks with vigour, and by his skill and determination he has succeeded in flying back to base safely.”—(as published in FLIGHT magazine, 20 August 1942.) In 1957, as part of a program to honour Canadian veterans and units, Donnelly Lake in Canada’s Northwest Territories was named after the young pilot—(61° 34’ 1” N, 106° 24’ 3” W). Photos via Rob Wethly

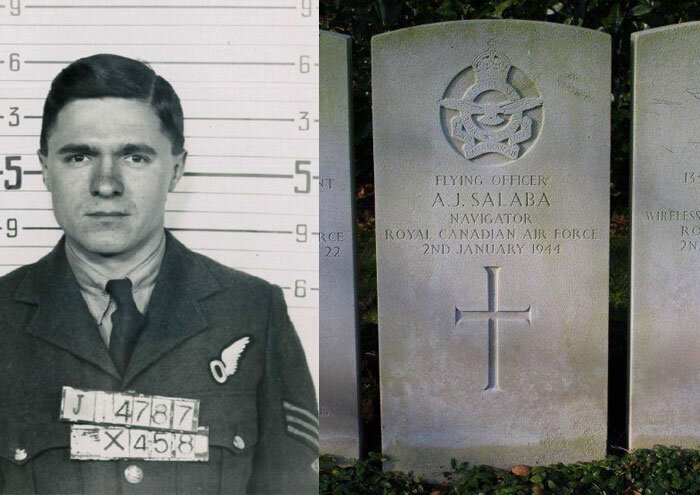

The Navigator aboard JB280 was Flying Officer Alexander Jerry Salaba (J/14787) of the small town of Willow Bunch in Southern Saskatchewan (population 325). He was the son of two Czech immigrants, James and Mary Anne Salaba (nee Slawich), and had one sister and four brothers, one of whom (Philip) was his twin. He was 28 years old. Like Donnelly, he has a lake named in his honour. Salaba Lake (57° 45’ 0” N, 103° 41’ 2” W) is in Northern Saskatchewan. Nearby Wollaston Lake Lodge has this to say about Salaba Lake: “Salaba Lake is near Morell Lake and offers the same type of Northern Pike and Walleye fishing. It is basically unexplored, but trophy Pike have been caught here – large weed beds were found to be full of the toothy critters. Shore lunch size Walleye were not a problem to catch throughout the season as well. So far, it’s known as a great “action lake,” but has big potential for trophy fishing. Three 16-ft. boats are based here.” No doubt, Alex Salaba would have been proud. Photos: Left: Canadian Virtual War Museum; Right: via Rob Wethly

Sergeant Ronald “Ron” Zimmer (R/186556), the top turret Air Gunner aboard Lancaster JB280, was, at 20, the youngets of the crew. Like many Saskatchewanians who died in the war, he was honoured by naming a geological feature (a Geo Memorial) after him—Zimmer Island in eastern Lac La Ronge (one of the largest lakes in Saskatchewan.) Photos: Left: Canadian Virtual War Memorial; Right: via Rob Wethly

Flight Sergeant William Leonard John “Jon” Clark (R/157740), JB280’s Bomb Aimer, was born in Brentford, England, but moved with his parents to Vancouver, British Columbia. The eldest child of William and Isabel Clark, he had three sisters (Phyllis, Eileen and Joan) and four brothers (Jack, Bob, Gordon and Harry.) Clark trained at No. 8 Bombing and Gunnery School in Lethbridge, Alberta. While stationed in Edmonton, he met his fiancée, Alice Grosco, with whom he corresponded nearly daily. He wrote a poignant poem for Alice while serving with 405 Squadron: “If death should come by moonlight / I shall not be afraid / He comes, a friend, to blot out hell / Man made / And when the pain’s forgotten / This I know I’ll do— / In that long and endless sleep / I’ll dream, my love, of you.” On New Year’s Eve 1943, he met up with his brother Jack (also in the RCAF) and enjoyed some time together. A few hours later he was shot down and killed in Holland. He was just 22 years old when he died. Photos: Left: Canadian Virtual War Memorial; Right: Via Rob Wethly

Rear Gunner Sergeant Ronald Everest Watts (1818766) Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Watts was 33 years old, the oldest of the crew. He was the son of John and Florence May Watts of Market Harborough, Leicestershire and was married to Kathleen Mary Watts. Unlike most aircrew in Bomber Command, he had children. Photos via Rob Wethly

Flight Engineer Sergeant Leslie George Robert Miller (1603616), Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Photos via Rob Wethly

Flight Engineer Sergeant Leslie George Robert Miller (1603616), Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Photos via Rob Wethly

As the sun came up over Nieuw-Schoonebeek, on that terrible Sunday morning, there was no thought of going to church… at least not yet. In the thin light of winter, townsfolk set to the grim and fruitless task of searching for survivors and policing up the broken youth of the Royal Canadian Air Force. According to the official report filed by local military police chief Hendrik Rinsma, three of the bodies were found intact, two others were in pieces scattered about and God knows how the other two were found. It was clear from the craters, or perhaps detonations, that four bombs had exploded. They had no way of knowing how many bombs the aircraft had been carrying.

They were buried three days later in the Schoonebeek General Cemetery where they remain today. Some time later after their identities were known, white crosses were erected with their names, ranks and service numbers painted on them. As tragic and traumatic as the destruction of JB280 and her crew was, it was not much more than a brief side note in the litany of death and suffering that was the Second World War, one of 28 such events to happen on that night alone in that sector. It warranted but three typewritten lines in the 405 Squadron Operational Record Book for January 1944. It was imperative that Wing Commander Reg Lane and his 405 Squadron move forward and put the horrors they witnessed every night behind them. There would be time to weep after victory.

While Canadians have let the seventy-two years of intervening time fade the memories of all of our lost youth of the Second World War, the Dutch have most definitely not. Perhaps it is gratitude. Perhaps it is the fact of the flaming Lancasters full of courage that came to dash themselves upon their soil. Perhaps it is the memory of their terrible suffering at the hands of the Nazis and the rushing elation of liberation that drives them to remember. I’ve said it many times before and I will say it again, the Dutch are better at remembering Canada’s fallen than Canadians. While we should be grateful, we should also be ashamed.

The story of JB280 and the Donnelly crew did not end with their burial. Throughout the seven decades since that terrible, but all-too-common, event in the opening hours of 1944, the townspeople of Oud-Schoonebeek have tended the graves and paid homage to the seven fallen men of JB280 as well as several other young men whose lives came to an end along with their aircraft near Schoonebeek. Like many village cemeteries throughout Europe, the original white crosses have been replaced by the now tragically ubiquitous granite tablet headstones of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Like many such beautiful places throughout Europe, the headstones of Donnelly’s crew have been meticulously tended and loved by the people of Nieuw-Schoonebeek. Here, on Christmas Eve, 2015, the members of Study Group Air War Drenthe (SLO Drenthe), a society dedicated to the preservation of the stories of men like those aboard JB280 and their brethren, light votive lights at each of the fallen’s headstone. Photo via Rob Wethly

But the story doesn’t end here. Just three weeks after the Christmas Eve memorial, Rob Wethly, a passionate history enthusiast from the Schoonebeek area, made a startling discovery that was in fact the closing act of that tragedy of 72 years ago.

72 years later — JB280 delivers her final payload

On a Sunday morning in mid-January of this year, Dutchman Rob Wethly was getting a little tired of listening to his two sons Yannic and Yde bickering as young boys will do when they are kept indoors. Sibling rivalry was getting on his nerves and after several warnings to behave, it was time to get the boys outside in the fresh air. Outside, the weather was clear, cold and sunny. “Good enough to go outside and let the boys cool down and get rid of their energy,” states Wethly.

The two boys and their father shared a common pastime—using metal detectors to search for artifacts on farms and in fields—largely metal objects from the Second World War, which had been fought on this very ground and in the air overhead more than 70 years ago. It is a fact that the people of the Netherlands are more passionate about military history and far better at commemorating Canadian sacrifices during that horrific war than Canadians are. It’s a sad commentary on Canadian patriotism, but a fact that is greatly appreciated by those of us who see what the Dutch have done to remember our fallen.

One of the Wethly boys’ favourite spots to scan for metal fragments from the war is near their home in Schoonebeek, Drenthe on the German border—a place where, 72 years ago, on the night of 1–2 January, Avro Lancaster JB280, in flames and shedding parts, came roaring down out of the darkness and slammed into a farmer’s field. Along with the falling debris from the dying Lancaster came 7 young men, four 1,000 lb. bombs, one massive 4,000 lb. bomb known as a “cookie” and more than three quarters of a full fuel load. The horrific end of the Lancaster and its young crew on that opening day of 1944 can only be imagined. The destruction and subsequent explosion of the bomb load of the Lancaster spread aircraft components and bomb fragments over a wide area.

Dutch military history enthusiast Rob Wethly and his two sons (Yannic, 12 and Yde, 9) use their metal detectors to search for fragments of metal that connect them with powerful events that happened in this field long ago. It was on just such an outing that the three made a remarkable, and very dangerous, discovery which would bring to light a long forgotten story of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Photo via Rob Wethly

Rob Wethly, his sons and friends have unearthed metal bomb fragments (shrapnel) and small parts from JB280. Photo via Rob Wethly

Other Lancaster components found by Rob Wethly and his young boys. Photo via Rob Wethly

Wethly and the boys headed to one of their favourite spots in the crash area where, on previous outings, they had luck in finding bomb casing fragments and other Lancaster parts not collected up by the salvagers 72 years ago.

Dressed in rubber boots and warm clothes, the three began a systematic search, walking slowly and sweeping their metal detectors back and forth across the cold and wet Dutch soil. It was a joy for Wethly to share this activity with his two active sons—on many levels. Just to be out with the boys, spending time together in the fresh air was enough, but the activity gave them an appreciation for the tumultuous history that took place here those many decades ago. It was overhead here, on this spot, that streams of Wellingtons, Lancasters, Halifaxes and Stirlings had droned unseen through the night on their way to German industries and cities. The young boys were enthralled by the tales of courage and sacrifice, and were keen to find and touch fragments that profoundly connected them to their history. Much like young boys growing up in Canada who find ancient Indian arrowheads along a creek bed, Yannic and Yde thrilled at every find, looking to strengthen their connection with those Canadians that gave them freedom.

Rob Wethly, at 52 years old and former Dutch soldier, is too young to have a memory of the war, but his father no doubt taught him about the war, the deprivation, the terrors and the heroic Allied airmen and soldiers who fought their way across the lowlands from the sea, eventually, through great sacrifice, liberating his country. He is a passionate history enthusiast as are many men and women in the Netherlands. Like most of them, his passion is focused on the powerful, emotional and terrible years between 1940 and 1945. For Wethly, the passion extends far beyond the thrill of finding metal from a Lancaster. Along with fellow enthusiasts, he spends considerable time researching archives from Holland to Canada and beyond, piecing together the story of the airmen who fought directly overhead his home.

He is the co-founder of a small study group called Study Group Air War Drenthe and their stated goal is “To secure this piece of local history, preserve and share it by setting up small exhibitions and providing guest lectures at schools in our region. Our primary goal is to keep the remembrance alive of all the brave air men.” In doing so, he has taken the stories of his father, added research and artifacts and created a lasting tribute… and a new generation of young Dutch boys who will no doubt add to the wealth of knowledge as they follow in their father’s footsteps.

Wethly’s plan was to detect for metal for about an hour before taking 12-year-old Yannic to his drumming lesson—something that would also absorb some of his youthful energy. Metal detection is an addiction of sorts. There is a rush, a speeding of the heart, when a tone is heard from the machine. Perhaps it is a rush of hope—of finding a lost Zippo lighter, a lost wristwatch or ring which, if engraved, could be returned to the family and after seven decades bring closure and pride to aging loved ones. Just a few minutes into their sweep, they heard a signal, a weak one. Their hopes were up, but they lost contact with it—like a U-boat slipping silently away from a sonar sweep. Two minutes later, Wethly had another tone—much stronger and brighter than the previous one. Its strength indicated it was large, and not too deep.

Waving the search head over the spot, Wethly determined where best to dig, and with a small shovel, carefully dug an inspection hole about 16 inches (40 cm) deep. In the deep clay and mud, he hit something hard. “Finally,” explains Wethly, “I found some metal. It was curved in shape and I thought it must be part of a typical oxygen tank used on Lancasters. I used my probe to determine the dimensions and I noticed that it was too big for what I knew about an oxygen tank from a Lancaster bomber. Yannic checked the inspection hole with our pin pointer (a small hand-held metal detector) and was able to show the direction of the object. It crossed my mind that it could be a bomb. I told the boys that I would dig a small hole in the line of the object, but a little bit further back and if I still found the same kind of metal, then it must be a bomb. I sent the boys away to a safe place and used my cell phone to call my colleague and very knowledgeable air war researcher, Geert Bos, for assistance and advice. I then dug the other inspection hole and used the probe again to determine if I could still see the object. With a hard brush I removed some dirt and discovered the front fuse of the bomb. This was the moment for me to step away and walk to a safe distance and to tell Yannic and Yde what we had found.”

Geert Bos showed up at the site in short order, and with the boys at a safe distance, they went to inspect the bomb. Confirming the find, Bos and Wethly returned to their car and called the police.

Wethly explains what happened next:

“With the arrival of the police, we discussed our finding and then called in the police bomb scout. After his arrival and inspection, he concluded the same as I did, that it must be a 500 lb. bomb. We informed the landowner and told him that the Army bomb disposal group (EOD) was called in and that they will start on Monday morning with inspection.

The bomb was far enough from houses and farm buildings and not a real threat for people in this remote farm land. Because I was able to tell the police the whole story about Lancaster JB280, they asked me to send my reports and documents to the Army bomb disposal group. They in turn invited Geert and I to be present during the operation and we were allowed to get close to the bomb while they did their job. It was nice to work together, they asked questions about JB280 and liked the way I handled the finding of the bomb.

We discussed the whole event from what happened in 1944 and what I had found with all my research into JB280. During their work they told me it was not a 500 lb. TI bomb but rather a 1,000 lb. MC bomb.

Monday was an entire day of preparation for EOD, the excavation of the bomb and the final decision to do the disposal with explosive in situ without moving the bomb. During Tuesday morning, the bomb was covered with a sand pile of 450 cubic metres and the demolition scheduled for 1 o’clock. Tuesday morning local and national press, radio and television agencies contacted me for interviews and we arranged with Yannic’s and Yde’s schools to allow them to be present. What a complete media circus it was!

The boys enjoyed it, as I did and Geert was also present, taking most of the pictures. Because of all the interviews and talks with people who wanted to know the story, I wasn’t able to take more than just two photographs that day. The landowner was asked to push the button and detonated the bomb on his land and what an explosion it was!”

72 years, almost to the day, that last bomb aboard Lancaster LQ-K, JB280 exploded spectacularly but harmlessly in Holland, a few hundred metres from Germany. Donnelly, Clark, Salaba and Zimmer never would set foot again in Canada and West, Watts and Miller would never go home. But thanks to men like Rob Wethly and Geert Bos their stories are not forgotten. The future belongs to Yannic and Yde.

Dave O’Malley

An RAF propaganda photograph from the Second World War showing the various types of bombs carried by Lancasters—from the 40 lb. General Purpose (on the shoulder of the armourer at centre) to 500 lb. bomb to the massive 12,000 lb. Tallboy and the 22,000 lb. Grand Slam. The 1,000 lb. MC bomb found on Huser’s farm is similar to the one shown in the foreground. The fins at the back were no longer attached to the bomb found by the Wethlys. Photo via Imperial War Museum

The 1,000 lb. Medium Case, General Purpose bomb from Lancaster JB280 exposed to the light of day for the first time since the night of 2 January 1944. These bombs came with one of two types of fuses—an instantaneous contact fuse in the nose and a long-delay (up to 144 hours) fuse in the tail. As the nose of this 1,000 pounder is smooth, this was a long-delay fused bomb. The fusing was clearly damaged in the crash and the bomb was never fused, lying dormant but very much alive for more than 70 years. This type of iron bomb was used for Area Bombing Raids (Industrial demolition.) Photo: Geert Bos

Dutch explosive experts and Rob Wethly (left) discuss the tragic events of 2 January 1944 and try to piece together just how the bomb they are about to excavate came to rest in this spot. Photo: Geert Bos

Demolition experts from the Dutch Army fully expose the Lancaster’s bomb prior to moving the bomb to an open field. Though this bomb looks more like a 500 pounder than a 1,000 pounder in terms of scale, but the 405 Squadron ORB clearly states that LQ-K was loaded with four 1,000 lb. MC and one 4,000 lb. HC (cookie) bombs. The Unexploded Ordnance crew covered the bomb with a pile of earth and detonated in situ. Photo: Geert Bos

Two photos of the explosion of the 1,000 pounder clearly show that its lethality was very much intact 70 years after it was manufactured, loaded and then lost. Photo via Rob Wethly, Geert Bos

Additional photographs of some of the crew of LQ-K. 1. A studio photograph of Navigator Salaba. Studio photos were invariably taken in order to give loved ones a high quality image before heading off to combat. 2. A studio photograph of “Jon” Clark, sporting a pencil-thin mustache and his correct Bomb Aimer’s brevet. 3. An RCAF photo of Clark showing his service number—taken after his promotion to Sergeant and receiving his wings. He is wearing the winged “O” brevet of a trained Navigator, instead of his Bomb Aimer wings. Earlier in the war, “Observers” were trained in multiple disciplines — navigation, bomb-aiming, radio and gunnery, but specializing in one area. Later on, crews were trained in specific skills such as bomb-aiming or navigation or gunnery and received wings for that specific skill. Pilots preferred bomb aimers or navigators who had been trained under the old method as they had multiple skills and understood all roles in the aircraft even if they operated solely as a navigator or bomb-aimer. 4. Pilot Donnelly’s temporary cross erected by the people of Oud-Schoonebeek days after his death. 5,6. Photos of Clark before and after his successful completion of the Bomb Aimer’s course at Lethbridge, Alberta. Left: With the winged “O” on his battle dress jacket and Right: as a young student wearing his aircrew in training white cap flash. 7. RCAF photo of Ronald Zimmer after earning his Air Gunner brevet. 8. The temporary cross erected by Dutch citizens for Zimmer’s burial. 9. A studio photograph of Zimmer looking well coiffed.Photos via Canadian Virtual War Memorial and/or Rob Wethly