RED TAIL — Dr. Eugene Richardson at Vintage Wings

During the Second World War, would-be black aviators like 18 year-old American Eugene Richardson knew they would be called upon to fight their war on two fronts. Before they could show the world and their own country that they were courageous and capable fighter pilots, they had to fight their way into the cockpits of their aircraft through a minefield of hatred and bigotry. Before 1941, there were no black pilots in the United States Army, but Congress legislated the Army Air Corps to accept them and to form up a new combat unit made up of black aviators. The Army's response to legislation requiring them to recruit African American men for pilot training was to set the bar so high for these men that they would get no applicants, The plan, however, backfired when the Army Air Corps was flooded with applications from men who met even these restrictive requirements

Beginning in March of 1941, black enlisted men began training in the numerous support roles necessary to keep a squadron flying under combat conditions. Early training started at Chanute Field in Illinois, but the 99th Fighter Squadron really took shape when the unit moved to the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama.

The Army chose the Tuskegee Institute to train pilots because it had a well-demonstrated commitment to aeronautical training. Tuskegee also had the facilities as well as engineering and technical instructors, and of course a climate conducive to year round flying operations. Tuskegee became the centre for training of African Americans for air operations during the Second World War. Today, the airfield where they once trained is now known as the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site.

Primary flying training began at Moton Filed (named after Tuskegee University's second president) and pilots were moved on to Tuskegee Army Air Field for conversion training to operational aircraft types. Those who trained in the so-called "Tuskegee Experiment," the Army Air Corps program to train African Americans to fly and maintain combat aircraft, were known as "Tuskegee Airmen". The name was applied to all pilots, navigators, bombardiers, maintenance and support staff, instructors, and all the personnel who kept the planes in the air. It was still some time and still an uphill battle to get the House Armed Services Committee to commit them to combat. Eventually, through persistence, the 99th joined two new all-black Tuskegee-trained fighter squadrons to form the 332nd Fighter Group.

Beginning with the 99th in North Africa and Sicily, all three Tuskegee squadrons saw combat. Most joined the fight in the European Theatre of Operations and their combat record proves their worth. For many years the Tuskegee Airmen were said to have never lost a bomber they were tasked to escort. Though this is erroneous, these valiant pilots were credited with shooting down no less than 109 German aircraft while flying over 15,000 sorties during 1,500 missions. They earned 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and 744 Air Medals, which is truly remarkable when one notes that only 445 of the 992 Tuskegee-trained pilots were ever deployed overseas for combat. 150 black airmen were killed in training and combat - making the ultimate sacrifice for the country that resented them so much.

Tuskegee pilots pose for a pre-mission photograph with one of their Red Tail P-51 Mustangs on a pierced steel planking hardstand somewhere in Europe (possibly Italy) during the Second World War. A long range drop tank can be seen slung under the wing.

Related Stories

Click on image

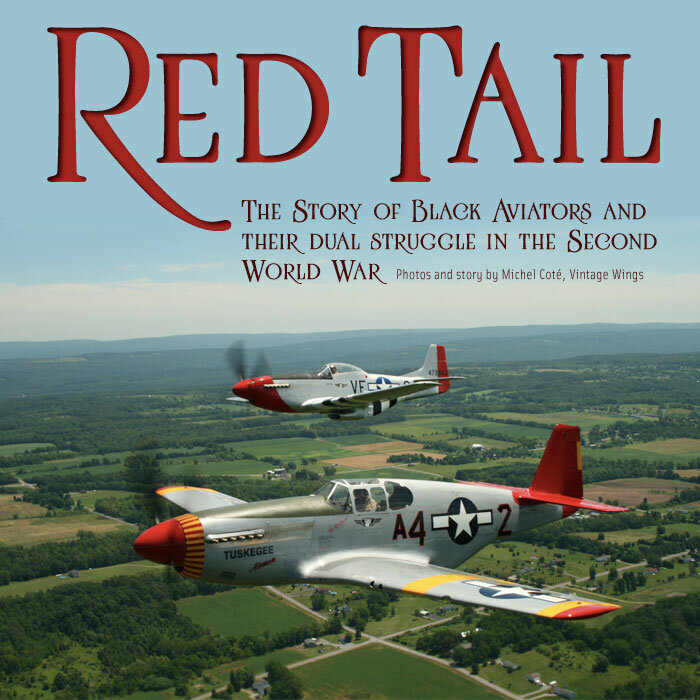

Their combat record went a long way to changing the mindset of those they worked with - bomber crews often requested them for escorts, enemy pilots respected their courage and they earned themselves a nickname "Red Tails" for the distinctive all-red tail surfaces they sported.

Now, in September 2007, a surprisingly youthful octogenarian and much-lauded educator, Dr. Eugene Richardson and his beautiful wife Helen were the guests of Vintage Wings of Canada for a personal tour of our collection and facility. A delightful man with a direct manner, an infectious sense of humour and warm handshake, Richardson was accompanied by United States embassy staff, who were just as charmed with him as were Vintage Wings volunteers. He needed no cajoling to step into the cockpits of the Spitfire and Mustang. Sitting next to him on the wing of the Mustang, I watched as his hands touched all the controls and he named them all quietly to himself, remembering those powerful days so long ago. Though he never flew the P-51, which was considered the quintessential "Red Tail" mount, Eugene was qualified to fly the massive Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the Curttiss P-40 Warhawk. He had everyone laughing when he shouted "Contact" from the cockpit. Later, Vintage Wings of Canada pilot John Aitken and Richardson shared some private time together as John showed off our newly arrived Canadair Sabre 5 (North American F-86).

The Richardsons were in Ottawa as guests of the Embassy of the United States of America to give a presentation about the Tuskegee Airmen at the Canada Aviation Museum. From Vintage Wings, Eugene was to return to the Museum to give his presentation and there could be no better way to arrive there than by warbird! So it was planned to surprise him with a chauffeured flight in our immaculate Harvard 4. A quick check with Mike Potter to see if this was OK met with this four word response: "A Tuskegee Airman? Absolutely!"

While John Aitken flew Eugene northwest to view the fall colours of the Gatineau Hills and then on to the Canada Aviation Museum, the rest of us looked on with admiration and pride. Eugene belonged in the air. It was a great day for Eugene and for all of us who got to spend this brief time with him

Contact! Leaning from the cockpit of the Vintage Wings Mustang, Eugene Richardson warms up the crowd with a little pilot humour. Photo: Michel Coté

Ever the educator, Dr. Eugene Richardson explains the function of the rudimentary air speed indicator on the Vintage Wings Tiger Moth to United States Embassy staffers who escorted him to the hangar. After the war, Richardson went to college and earned a doctorate in education. He became a high school principal and now as a retired educator tours the U.S. (and Canada) speaking about and teaching the story of the Tuskegee Airmen. Photo: Michel Coté

The look on Dr. Richardson's face says it all. It was his first time in a Sabre and he was as excited about it as the 18-year old Richardson who joined other black aviators in Tuskegee must have been. Though already transitioned to the mighty P-47 "Jug" and the Warhawk, the war ended before Eugene was sent overseas. Happy not to have to kill and to be killed, Eugene was de-mobilized and sent home - he was still just 21 years old. Eugene's experiences inspired a generation of African Americans including his own son, Eugene Richardson III, who became a fighter pilot and an airline executive. Photo: Michel Côté

Eugene Richardson and John Aitken pose for a flurry of picture taking prior to their flight back to the Canada Aviation Museum via the Gatineau Hills. Many thanks to the Embassy of the United States for sponsoring his trip to Ottawa. Photo: Michel Côté