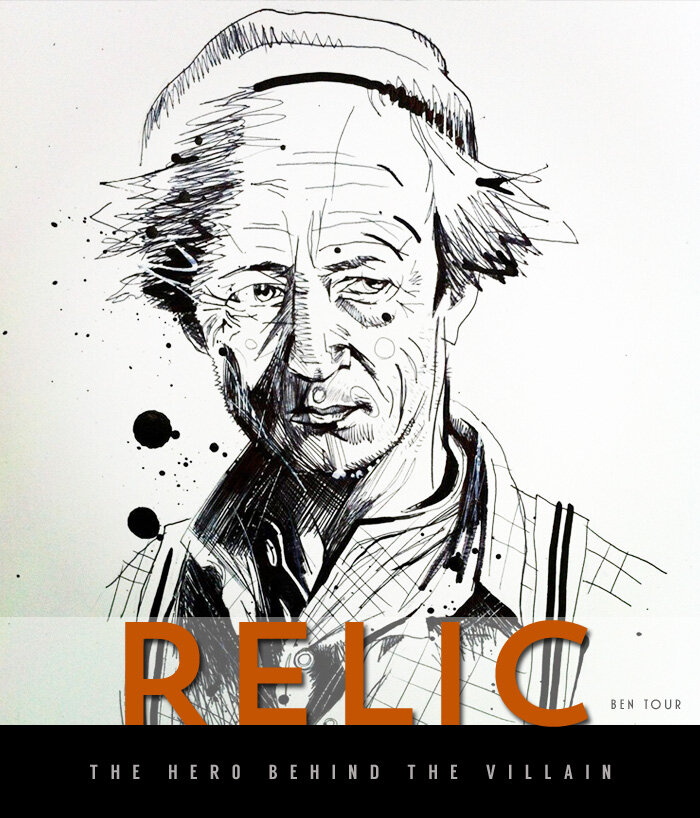

RELIC – The Hero behind the Villain

Recently, we lost that great British dramatic actor Richard Attenborough, whose role in The Great Escape set the tone for the great laconic and stoic British war heroes depicted thereafter. In 1963, Attenborough appeared in the big ensemble cast, playing the part of RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett (known as “Big X”), the head of the escape committee—a screen character roughly based on the real-life escape exploits of South African Roger Bushell. Attenborough, an actual veteran of the war, was one of several in the cast who had participated in the Second World War.

Attenborough served with the Royal Air Force during the war. After elementary flying training, he was scooped up for the newly formed RAF Film Unit, acting in propaganda films. He volunteered to fly with the Film Unit and flew on several Bomber Command operations as a cameraman in the rear gunner’s position, recording the outcomes of the bombing raids.

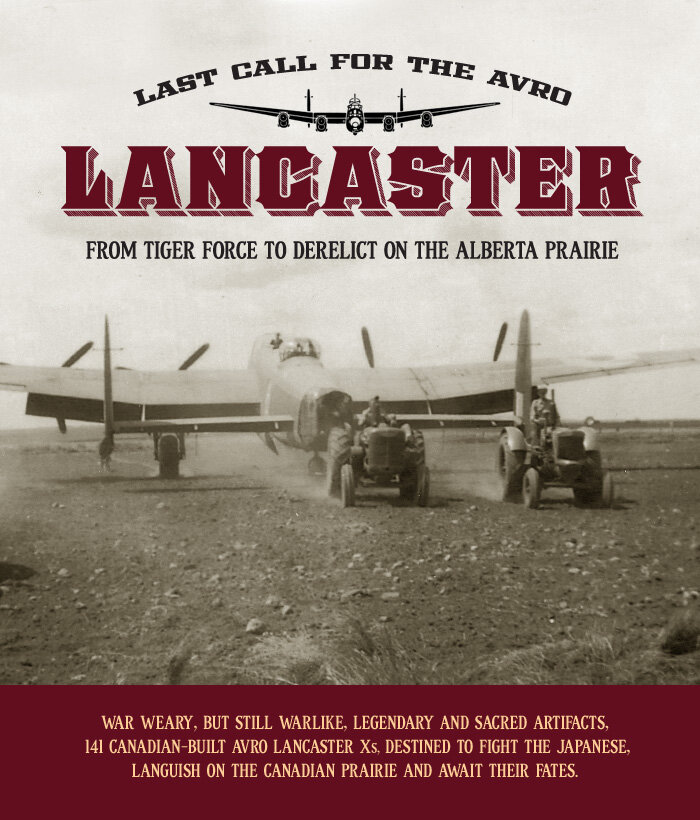

Starring with him in the film was British actor, Donald Pleasence. Pleasence began the Second World War as a conscientious objector, but later, witnessing the Nazis in action, changed his mind on participation and was commissioned into the Royal Air Force, serving as a bomber pilot with 166 Squadron. His Avro Lancaster was shot down on 31 August 1944, during a raid on Agenville. He spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp where he produced and acted in plays. In The Great Escape, he played the part of Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe, the nerdy forger who went blind while creating false documents.

Another great heroic actor of note in The Great Escape was Charles Bronson. Born Charles Buchinsky in Pennsylvania, Bronson was a gunner on a B-29 Superfortress in Guam, with 25 missions over Japan. Other combat veterans in that cast included James Garner, Hannes Messemer and Nigel Stock.

These men from The Great Escape were just some of the many veterans of the Second World War who found work and fame as television and screen actors after the war. Many, if not all, at one time or another played heroic military roles in the glut of hundreds of epic war films that came out in the three decades after the war—films like The Guns of Navarone, Twelve O’Clock High, The Enemy Below and The Bridge over the River Kwai. They were believable, steely-eyed, powerful, iconic. Because we know them as heroes of film, it seems a short stretch to see them as actual heroes who did their duty during the Second World War or Korean War. It’s not hard to see David Niven as a British Army officer, because he was. It’s not a stretch to see Charles Bronson as a Polish airman, for in real life, he was both Polish and an airman. Some, like Jimmy Stewart, continued both careers in parallel. It wasn’t hard to see Stewart as a Strategic Air Command bomber pilot... because he was exactly that.

Richard Attenborough, playing Squadron Leader Roger “Big X” Bartlett in The Great Escape—the epitome of the determined British hero. Screen capture: United Artists

British actor and former Bomber Command Lancaster pilot Donald Pleasence channelled personal experience in a Prisoner of War camp during the Second World War to portray the part of myopic and soon-to-be-blind document forger, Flight Lieutenant Colin Blythe in The Great Escape. Screen capture: United Artists

The Beachcombers and Flight Lieutenant Robert Clothier, DFC

There once was a Canadian comic-drama television series called The Beachcombers. It ran from 1972 to until 1990 and it holds the record for the longest-running television drama series ever made for English-language Canadian television—387 episodes in all.

The Beachcombers was pretty lame by today’s standards, set by uber-gritty serial dramas such as Breaking Bad, The Sopranos and House of Cards. It caught just enough of the Canadian character to resonate with Canadians who were not looking for evil, injustice and depravity, the underlying DNA of modern television. They were looking for a simple structure, a simple way, a simple life, where the villains were foolish and, at times, likable. The storyline was centred around the life and community of a Greek-Canadian beachcomber by the name of Nick Adonidas. His way of making a living was to search the beaches of British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast, looking for logs which had become beached after breaking loose from commercial log booms. Using his powerful boat he would hook them up and drag them off the beach and sell them back to the logging company—a decidedly Canadian storyline. The series was translated into five languages and ran in 37 different countries including the United States, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand and Germany.

Nick’s nemesis in the series, and one of its most recognizable characters, was nicknamed “Relic”, a middle aged, unkempt and unsavoury character by the full name of Stafford T. Phillips, who was also a rival beachcomber. Actor Robert Clothier, as Relic, delivered a tour de force character that everyone could hiss and boo at, but was non-threatening, even bumbling. Without Relic, there was simply no heart to The Beachcombers. His job, one which he delivered time and time again, was to make everyone seem normal, well-meaning and hard working. If you asked any Canadian older than 40 today to name a character from The Beachcombers, it will be Clothier’s Relic who is remembered first. Adjectives for Relic include shifty-eyed, untrustworthy, sneaky, dirty, despicable, complex and larcenous. He was a thoroughly disreputable character, but Robert Clothier, the actor who created him, was the opposite in every way. While Canadians love to despise Relic, very few of them know that the man who played him was a Canadian war hero with a back story both tragic and triumphant—one that perhaps gave him the inner grief and I-don’t-give-a-damn aloofness to play the part of the country’s most reviled, yet strangely loved, character.

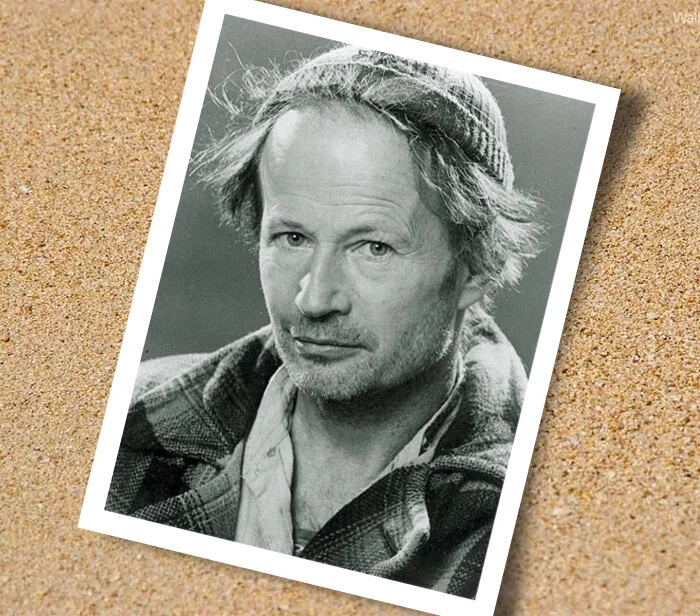

Flight Lieutenant Robert Clothier, DFC played the part of Stafford T. “Relic” Phillips, the scruffy and ill-mannered log scavenger in 213 episodes of The Beachcombers, a long-running drama produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Photo: CBC

According to IDMb.com, Relic, an acerbic loner, was always surly and ill mannered. A miser, he rarely did anything unless he could profit by it. As the primary competitor of Nick Adonidas (right, played by Bruno Gerussi) many of the show’s episodes had him competing with Nick over something, usually with Nick on the higher moral ground. While sneaky and dishonest Relic would frequently find ways to cheat, though he was usually careful to avoid breaking the law. There were also several episodes in which Relic played the central character. Photo: CBC

A nice colour photo of Clothier sitting on the gunwale of his beachcombing boat, the High Baller II, looking filthy and dishevelled and worthy of the name Relic. Photo: CBC

Related Stories

Click on image

Robert Clothier was a British Columbian through and through—the son of a silver mine owner from Prince Rupert. He was born in BC in 1921 and died there in 1999. When war broke out, Clothier enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force on his 19th birthday. He journeyed to Toronto’s No. 1 Initial Training School, where he learned to dress, march and behave like an airman. He graduated the following March as a Leading Aircraftman and found himself selected for pilot training.

Within a few weeks, Clothier was doing his Elementary Flying Training (EFTS) on de Havilland Tiger Moths at Malton’s No. 1 EFTS at the airfield that is today Toronto’s Lester B. Pearson International Airport. After his time at Malton, he was selected for multi-engine Service Flying Training (SFTS) and sent to No. 4 SFTS in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan where he earned his wings on the Avro Anson and Cessna Crane. Upon earning his RCAF pilot’s brevet, he was promoted to Sergeant and sent to Great Britain for his Operational Training, starting in August of 1941.

After his Operational Training, he joined 408 Goose Squadron of the RCAF in March of 1942, flying the Handley Page Hampden medium bomber. 408 Squadron had just been formed the previous summer at RAF Lindholme and was then based at RAF Syerston. After familiarization flights, Sergeant Robert Clothier’s first combat sortie was on the night of 26–27 March 1942. The 408 Squadron Association and history website (ForFreedom.ca) indicates that on that night the squadron was involved in a mine laying or “gardening” operation with the loss of three aircraft. Within a few months, he was commissioned as a Pilot Officer. We have little information about the operations he flew in his first tour, but one record with the Bomber Command Museum of Canada indicates he had flown his 22nd combat sortie on 11 July 1942.

Flight Sergeant Robert Clothier (left) at his Handley Page Hampton Operational training Unit for pilots and navigators (observers) in October of 1941. Photo via theygavetheirtodsay.com

A 408 Squadron RCAF Handley Page Hampden warms up off the taxiway across from Hangar 7 at RAF Syerston. The Hampden was nicknamed the Flying Suitcase by its crews for its cramped crew accommodations. During one of Clothier’s combat ops, he was shot at twice by the nervous crew of a Vickers Wellington, who likely mistook him for a twin-engined Dornier Do-17 night fighter, which had a very similar configuration. Photo: Bomber Command Museum of Canada

By the time he had finished his first tour, Clothier, who was now flying the much more capable Handley Page Halifax four-engined bomber, was promoted to Flying Officer (9 December 1942). There are a number of information gaps from the end of Clothier’s first combat flying tour to the beginning of his second. It appears that he may also have been repatriated for a spell, possibly after the start of his second tour, but he was posted overseas again, to his 408 Goose squadron in March of 1944. He was promoted again, to Flight Lieutenant, on 15 June 1944.

As nasty and amoral as Clothier was on screen, he was the opposite in real life—a decorated war hero, Bomber Command pilot and to all accounts an enthusiastic and elegant man. Here we see him with his entire 408 Squadron Halifax crew at RAF Lindholme, Yorkshire, Great Britain—a very experienced crew indeed with commissioned gunners and gongs galore. Left to right: Flying Officer L. Corbeil, Bomb Aimer; Sergeant J. McCart , Flight Engineer; Flight Lieutenant B. Austen, Wireless Operator; Flying Officer S. DeZorzi, Navigator; Flight Lieutenant Robert Clothier, Pilot; Flight Lieutenant T. Murdoch, Mid-Upper Gunner; Flying Officer B. Fitzgerald, Rear Gunner. In this one crew, Corbeil, Austen, Clothier, DeZorzi and Fitzgerald all had Distinguished Flying Crosses. Clothier would also fly the Bristol Hercules-powered Lancaster II when the squadron transitioned and moved to RAF Linton-on-Ouse in the summer of 1943. On 24 July 1944, Clothier flew 408 “Goose” Squadron’s 3,000th operation sortie when he took his crew to Stuttgart, Germany for a raid. Clothier must have been a really dramatic character even then as here we see him smiling wildly, wearing a scarf and toting a pistol in a gloved hand. Photo via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

This photograph, taken at the same time as the previous photo, portrays a very happy crew with a gentle, comfortable and smiling Clothier at the heart of that happiness. Photo: RCAF

The Bomber Command Museum of Canada has a pdf copy of part of Clothier’s logbook, covering part of his second operational tour—flying Lancaster IIs, the Bristol Hercules-powered variant of the Lancaster. Clothier has cut tiny photos (likely from a contact sheet) for each of his crew members and pasted them in his logbook. We have scanned them here (clockwise, from upper left): Flight Lieutenant Robert Clothier, Pilot, looking happy and full of youthful vigour; Flying Officer S. DeZorzi, Navigator at his station; Flying Officer L. Corbeil, Bomb Aimer; Flying Officer B. Fitzgerald, Rear Gunner; Flight Lieutenant B. Austen, Wireless Operator; Sergeant J. McCart, Flight Engineer (not sure why Clothier has written FIRED! on this photo) and Flight Lieutenant T. Murdoch, Mid-Upper Gunner. Records at Bomber Command Museum of Canada show that Clothier had DeZorzi as his Navigator on both of his operational tours, demonstrating the loyalty crew members had for each other. Photos from Clothier’s logbook via Bomber Command Museum of Canada

During his second tour, Clothier flew both the Lancaster II and the Halifax bombers from RAF East Moor. The Bomber Command Museum of Canada has a digital copy of Clothier’s logbook entries for the Lancaster II, starting from the end of his Heavy Conversion Unit training in late May of 1944 until 24 July of that same year, covering extensive training flights and 12 combat ops. It is known that Clothier flew 18 ops in total in the Lanc II and then went on to fly combat missions in Halifaxes. The author has seen references in news articles about Clothier indicating that he flew a total of 56 combat ops.

In one of Clothier’s logbook entries, the one for 2 July, he writes, rather understatedly: “Circuits and Landings... Shakey Do... Pranged... Cat B”. Clothier is so nonchalant about that day’s flight, one might consider it inconsequential, but he and his crew very nearly lost their lives. While practising 3- and 2-engine landings, Clothier was conducting a 3-engine touch-and-go in Lancaster DS621 with one engine powered down and feathered. On climb out, the two engines on the side opposite to the feathered engine simply quit... possibly a fuel problem. Climbing out, the Lancaster, now with only one working engine, was in very serious trouble. A less experienced pilot would have panicked in such a situation, but Clothier, who had 1,110 flying hours at that time, was able to belly land his Lancaster safely near the railway crossroads of Pilmoor Junction, some 15 kilometres to the northwest of RAF East Moor, the home base for 408 Squadron. The aircraft, DS621 (OW-U), belonged to 426 Squadron and had 411 hours on the airframe. Clothier’s skill and calm in an emergency situation likely saved the crew, who were no doubt too low to use a parachute.

A scan of a page from Clothier’s logbook tells us a few things about the man. First, his assessment by Flight Lieutenant Smith of A-Flight, following Conversion Training at 1664 Heavy Conversion Training Unit was “Above Average”. We can also see that he was training with his new crew and his old navigator De Zorzi. Clothier is then transferred back to his old squadron and we can see the signs of an artist in the way he titled the section pertaining to 408 Squadron. Scan via bomber Command Museum of Canada

Clothier’s last combat op flying the Halifax with 408 Squadron was on 10 September 1944. Beginning in early October, Clothier began the process which would repatriate him, and bring him close to his British Columbia home. He left Europe in late October and arrived at his new unit, No. 5 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Boundary Bay, south of Vancouver on 3 December 1944. No. 5 was a training facility offering advanced operational instruction on both B-24 Liberators and B-25 Mitchell bombers to recently breveted pilots. While the war in Europe was largely understood to be winding down, there was still the big war to the West, where the Japanese military and indeed citizenry appeared to be dedicated to fighting to the bitter end. Staff instructor pilots at No. 5 OTU were mostly combat veterans given what should have been easy duty—imparting their hard-won knowledge to novice pilots. But events would transpire later that month that showed just how dangerous this easy duty really was.

Two days after joining the staff pilots at No. 5 OTU, Robert Clothier was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross back in Europe, with an announcement gazetted in the London Gazette that day. The citation that accompanied his award of the DFC states: “This officer has completed numerous sorties in the role of pilot, involving attacks on most of the enemy’s heavily defended targets. On all occasions he has pressed home his attacks with great determination and by his personal example of courage, coolness and confidence has set an example which has inspired all with whom he has flown.” In a rather disturbing story of bureaucratic lassitude, Clothier’s DFC was not delivered to him until 1956... more than ten years later!

For the next few weeks, Clothier settled into a routine of flying instruction and familiarization flights, flying without the stress of impending combat. But two days before Christmas, he was involved in a flying accident that would change the course of his life. While taking off for a compass-swing test flight in a B-25 Mitchell on 23 December, Clothier’s aircraft lost power to one of its two engines. Having only been airborne for a few seconds, the crew attempted to get it back on the runway and stopped. The Mitchell ran hard off the end of the runway and into a large drainage ditch, where it impacted heavily and exploded. Clothier was known to never buckle his seat belt and, in this case, this bad practice actually saved his life, for he was ejected forward through the cockpit windscreen, the only one of the four-man crew to survive. One of the crew, Corporal Robert Dutton of Gilbert Plains, Manitoba, an instrument technician, was also thrown from the wreck. He died a few hours later in hospital of head trauma, burns and other injuries. The other tow crew members were consumed by a fire so intense that the aluminium of the aircraft melted and flowed as a liquid.

Clothier survived, but was gravely injured, having broken his back in 5 places. He spent the next two years convalescing in and out of hospital and was left with a limp that stayed with him for the rest of his life. He was retired from the RCAF in January of 1946.

The three other crew members in the crash of Mitchell HD315 were Corporal Robert Edward Dutton of Gilbert Plains, Manitoba, Flying Officer George Raymond Spencer of Thorold, Ontario and Flying Officer Thomas Leslie Walmsley of Toronto.

North American B-25 Mitchell bombers of the Royal Canadian Air Force line the flight line at No. 5 Operational Training Unit, Boundary Bay, near the city of Vancouver, British Columbia. It was here, in late 1944, that Clothier arrived to begin training new bomber pilots. Photos by Noel Barlow, DezMazes Collection, via No. 5 OTU Facebook page

An aerial photograph of RCAF Station Boundary Bay from the Second World War. To the left runs a deep ditch-like depression into which Clothier’s crippled B-25 Mitchell crashed, 23 December 1944. Photo: RCAF

A No. 5 OTU B-25 Mitchell in the skies over the Vancouver area. It was in a similar aircraft that Clothier received his only major injuries of his Second World War service, despite two operational tours. Photos by Noel Barlow, DezMazes Collection, via No. 5 OTU Facebook page

Boundary Bay fire fighters battle the intense flames following the crash of Clothier’s B-25 Mitchell. RCAF photo via The Bomber Command Museum of Canada

As Clothier lay recuperating from this terrible accident, he was dealt another, even more devastating, personal blow—the death of his brother John, also a Bomber Command pilot just starting his third tour. The circumstances surrounding the death of John Clothier likely hurt Robert deeply, igniting feelings of futility and anger towards the war and Bomber Command which may have stayed with him all his life. In later years, he spoke very little of his wartime experiences, even to his bride, the actress Shirley Broderick.

On the night of 5 March 1945, 25-year-old Flight Lieutenant John George Clothier and the crew of Handley Page Halifax QO-L (RAF Serial No. RG475) were making their way home, churning though the icy winter darkness. It was approaching midnight. The crew, from 432 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, were returning from a night raid on Chemnitz, Germany. They were exhausted, hungry and cold, but they were cheered knowing they were approaching the south of England, where they could turn for their home at RAF East Moor in the northern county of York.

The crew was not Clothier’s. He was on a “Second Dickey” sortie—a new pilot crewing up with another, more experienced, crew for his first operational mission, getting the feel of flying a real night mission into the dangerous skies over Germany. The second dickey pilot was an otiose member of the crew, hitching a ride into combat, with his own crew remaining on the ground back at East Moor while their leader was blooded. More often than not, the crew was that of a flight leader or even the squadron commander, who wanted to get a feel for the qualities of the novice pilot he would soon be leading. On this flight, Clothier was flying with Squadron Leader Edwin Alfred Hayes. The experienced crew, commanded by pilot Hayes (16 ops), was comprised of Clothier, the Second Dickey pilot; Flight Engineer, Sergeant D. Cooke, RAF (14 ops); Navigator, Flying Officer Colin Maxwell Hay, RCAF (19 ops); Bomb Aimer, Pilot Officer Joseph Dennis Ringrose, RCAF (14 ops); Wireless Operator-Gunner, Flight Lieutenant Glen Royal Harris, RCAF (8 Ops); Gunner, Flight Sergeant Marius Bendt Nielsen, RCAF (14 ops); Gunner, Flight Sergeant Gilbert Melbourne Orser, RCAF (11 ops). Both gunners were only 19 years old.

Clothier, however, did not need blooding, not even close. He was a highly experienced and commissioned officer who had already survived two full combat tours with Bomber Command as an aerial gunner. One could certainly have said he had done his duty, not once, but twice. Instead, after his second tour, he applied to be trained as a pilot. Having gone through elementary flying training, service flying training and operational training, he and his crew were fresh from a Heavy Conversion Unit. All he had to do was one second dickey flight and he would finally be ready to take his crew in a Halifax bomber deep into enemy country.

The raid on Chemnitz, part of a much larger and sustained effort called Operation THUNDERCLAP (including the bombing of Dresden), was an all-Canadian Bomber Command “do” with nearly all the squadrons of No. 6 Group participating. 86 Halifaxes from 408 Goose, 415 Swordfish, 420 Snowy Owl, 425 Alouette, 426 Thunderbird, 429 Bison and 432 Leaside squadrons streamed with 84 Avro Lancasters from six other Canadian squadrons—419 Moose, 424 Tiger, 428 Ghost, 431 Iroquois (today’s Snowbirds), 433 Porcupine and 434 Bluenose squadrons. The 12 Canadian squadrons dropped a heavy and hard rain on Chemnitz—1,064,000 lbs of high explosives. The results of the attack were devastating to Chemnitz, but also to the Canadians, with 19 aircraft shot down and 86 airmen killed. Heavy icing over England caused dozens of heavy bombers to scatter and divert to airfields across the south of England. Particularly tragic was the fate that awaited QO-L.

The navigator, Flying Officer Colin Maxwell Hay, DSO, set a course which took them across the coast at the seaside town of Walton-on-Naze. Hay, a highly experienced navigator, was awarded a Distinguished Service Order the previous September after taking over the controls of his Halifax when his pilot and aircraft commander was severely wounded, and flying it safely home to England… with little experience and no training as a pilot. A military decoration, the DSO was awarded at that time only to officers for meritorious or distinguished service, and was considered an award second only to the Victoria Cross.

As QO-L approached England and the Essex County coastline, relief was most certainly felt among the crew in the dark interior of the Halifax. The war was largely taking place over Germany now and it had been a while since fuel-poor German night raiders followed the bomber stream home to attack aircraft at their most vulnerable—as they landed. With one more “do” under his belt, his first as a pilot, Clothier was likely euphoric. As Hayes and Clothier crossed the English coast, an anti-aircraft battery mistook them for a lone enemy intruder and, with the safety of England now beneath them, they were shot down. No one survived the crash.

With the war winding down and less than two months to go before the cessation of Bomber Command strategic bombing, crews returning from a long night raid were less fearful of attack and were beginning to let their guard down. Though it was so very late in the progress of the war, just two nights before, on 3–4 March, the Luftwaffe had conducted Operation GISELA, an ambitious and large scale counterattack on Bomber Command aircraft as they prepared for landing in England after night raids. Junkers Ju-88 night fighters flew low across the North Sea and Channel, under radar coverage, and near 1 AM, attacked bombers as they slowed down for landing.

The remains of Bomber Command Halifax HX332 after Operation GISELA. This aircraft was flying at between 2,500 and 3,000 feet when it was attacked from below by a Junkers Ju88 night fighter, part of the GISELA force. It sustained serious damage and the Canadian pilot, 22-year-old Flight Lieutenant John Gifford Laurence Laffoley of Montréal, was unable to sustain control. He ordered his crew to take to their parachutes, with three of the crew surviving. Laffoley crashed near Spellow Hill Estate, between Boroughbridge and Staveley just after 1 AM. Five airmen lost their lives as a result of the crash. This image shows only one of the wings of the destroyed aircraft. The second dickey pilot, navigator and air gunner survived. Photo via wikipedia

It is difficult to ascertain the total number of aircraft shot down that night, but Luftwaffe crews claimed more than 20 bombers, mostly four-engine types while the RAF counted 32 aircraft lost or damaged over England. GISELA was costly to the Luftwaffe as well. With 34 night fighters lost or damaged, the Germans staggered. The next day, they repeated the attacks, but with less than half the aircraft. And the British were now waiting. GISELA was the swan song of the Luftwaffe’s offensive capability.

It is not recorded why the gun battery mistook them for Germans. It is likely that the severe icing encountered by 6 Group on their way home from the Chemnitz raid, which caused the Group’s aircraft to seek lower altitudes and which scattered many, combined with the previous nights’ attacks, contributed to the misidentification of the 432 Squadron Halifax—possibly lower than normal, possibly alone. Coastal batteries were likely on very high alert after GISELA, expecting German raiders at around the time that Bomber Command aircraft were due to land.

It was a tough pill to swallow for Robert Clothier, still convalescing after his crash in the Mitchell. It is likely he was angry at the apparent stupidity of the coastal battery at Walton-on-Naze and the loss of an entire and highly experienced crew with only weeks left in the war. Had he known about Operation GISELA, which had ravaged Bomber Command the two previous nights, he might have better understood why the battery opened up on them near midnight on that cold late winter night over the English coast.

Robert Clothier died in 1999 at the age of 77. He had suffered a stroke three years before and had been in poor health. During the last days and months of his life he was embroiled in a royalties dispute with CBC-TV for reruns and overseas sales of The Beachcombers. He is remembered by Canadians from coast to coast to coast for the miserable, conniving character he created, but he should really be remembered for his sacrifice to his country in the Second World War and his bright youthful character that was so wounded by events at the end of the war. His character Relic is a Canadian icon, but Robert Clothier is a Canadian hero.

After his long-running role as Relic in The Beachcombers, Clothier continued to act, appearing in film and television, while remaining a British Columbian to the core. The hugely successful television series, the X-Files, was largely filmed in Vancouver and Clothier made a couple of small part appearances in that series. Here we see him as “Old Man” driving a pickup truck with agents Mulder and Scully. Screen capture from X-Files

Robert Clothier’s crew photograph was selected from literally several hundred similar crew photographs from 6 Group and other Bomber Command squadrons to represent all others on Canada’s Bomber Command Memorial in Nanton, Alberta. The monument bears the names of the more than 10,000 Canadian boys who died on operations with Bomber Command. It is likely that the Clothier crew photo was selected for the quality of the photograph and the experience of the crew (most with 2 tours and a DFC), but I like to think that it is because of the looks on their faces—all handsome, innocent and wise, all smiling with promise and hope for a future that may extend beyond the bloody skies of Europe. I like to think it is because of their leader, Flight Lieutenant Robert Clothier, DFC—young, beautiful, open faced and roguish. Though it appears smaller in this perspective, the flag pole over the museum, flying the RCAF ensign, is over 100 feet tall. The flag itself is massive as well—40 feet by 20 feet. Metal from a crashed Canadian Halifax (LW682) is incorporated into the RCAF finial at the top of the pole. Photo via Bomber Command Museum

More than four thousand miles away from Nanton, Alberta, in Walton-on-Naze, a memorial was constructed in 1978 by the Royal Air Forces Association. The second Clothier brother, John George, is honoured with the other members of that unfortunate crew. The propeller blades were recovered from the crash site of Clothier’s Halifax by officers and cadets of 308 Squadron, Air Training Corps, RAF. The memorial is dedicated to the crew of the Halifax and all local men and women who have served with the RAF. No mention is made of the friendly fire incident. Photo: Oldpicruss

A close-up of the plaque at the base of the Walton-on-Naze memorial with Clothier’s name highlighted by the author. The two Clothier brothers gave more than most—four completed tours between them; Robert training pilots after his two tours, John upping for one more tour and retraining as a pilot. The death of John affected the life of Robert, there is no doubt. They deserve to be in these two quiet and very special places. Photo: Oldpicruss

The author would like to thank the Bomber Command Museum of Canada (BCMC) and in particular, the research efforts and passion of Dave Birrell, whose interviews with the Clothier family and dogged research has brought to light the story of both Robert and John Clothier, two British Columbians who left nothing on the table when it came to doing their duty during the Second World War. Dave Birrell and the indomitable Karl Kjarsgaard generously and enthusiastically assisted the author in the collection of materials regarding Clothier. The Bomber Command Museum of Canada, in Nanton, Alberta, does more than any institution in this country to bring to life the men, the machines, the stories and the memory of the Canadian boys who fought for Bomber Command. It took governments 7 decades to honour these men, but the men and women of the BCMC could not wait, and have created lasting memorials to our fallen—monuments, displays, educational events, and working aircraft. To learn more about the BCMC and to make a donation click here.

The author would also like to thank Ben Tour, the artist who created the ink portrait of Relic at the opening of this story. It captures much about the character Relic, but also the dignity and tragedy of the man who played him.

In addition, kudos go out to the 408 Squadron Association website—For Freedom, an invaluable resource in writing this article. “For Freedom” is the motto of 408 Squadron, RCAF.