ROUNDEL ROUND-UP

If I had a dollar for every time someone asked me, during a tour of Vintage Wings of Canada or at an air show: “Whaddya call that bullseye thingamajig there?” or “How come the bullseye on the wing has no white in it like the bullseye on the side of the plane?” or “Doesn't Canada have a maple leaf in their bullseye?”, I would be able to afford my own bullseye-emblazoned Spitfire. These curious neophytes, of course, are speaking about the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal Navy (RN) “roundels” which, for nearly a century, have identified aircraft in the service of the King or Queen of the realm. The truth is most people, even those who are knowledgeable about warbirds, have no idea where the roundel comes from, why certain roundels are used on aircraft of a certain vintage, or why there may be three different types of roundels on the same aircraft. This article tries to explain some of the history and demonstrate the use of the various roundel styles over the years. I do so at great risk of being labelled a seriously unbalanced, basement-dwelling aerogeek, lost in minutia and losing sight of the big picture. I also do so knowing that I actually don't know everything about the esoterica that is roundel usage and run an added risk of being ridiculed by those whose life work is the study of seemingly insignificant details. Despite the risks to my reputation and the possibility that I may be labelled a rivet-counting history whore, I do, in fact, find this very interesting stuff.

The Royal Air Force roundel of the Second World War is derived from the original Royal Flying Corps (RFC) roundel of the First World War, which was in turn derived from a traditional martial decorative device known as the “cockade”. The cockade is a knot of ribbon, or other circular- or oval-shaped symbol of distinctive national colours which was usually worn on a soldier's clothing, in particular on head gear. In the 18th and 19th century, various European states used cockades to denote the nationalities of their military. Even Union and Confederate soldiers of the Civil War often wore cockades or “rosettes” on their dress uniforms and for formal photographs. Along with NCO chevrons, brass buttons, ribbons, awards and epaulettes, the cockade was an item of military dress and distinction. More importantly, its colours were often those of the country it represented.

Left: A commemorative cockade from the French Revolution. Right: A bicorn hat, once belonging to Napoleon, decorated with a cockade.

When the First World War started in 1914, it was the habit of ground troops to fire on all aircraft, friend or foe, which “encouraged” the need for some form of identification mark on all aircraft. At first, the Union Flag was painted under the wings and on the sides of the fuselages of RFC aircraft. It soon became obvious that, at a distance, the St George's Cross of the Union Flag could be confused with the Iron Cross that was already being used to identify German aircraft – particularly from below and against the glare of the sky. After a Union Flag inside a shield was tried unsuccessfully, it was decided to follow the lead of the French air force which used a circular symbol resembling, and called, a “cockade” (a rosette of red and white with a blue centre). The British reversed the colours and it became the standard marking on Royal Flying Corps aircraft from 11 December 1914, although it was well into 1915 before the new marking was used entirely consistently. The Royal Naval Air Service meanwhile briefly used a red ring, without the blue centre, until it was sensibly decided to standardize on the RFC roundel for all British aircraft.

The ancestry of the Royal Air Force and Royal Canadian Air Force roundel can be traced to the French Revolution and then Napoleonic French soldiers. Counter clockwise from upper right: 1: A typical French Cockade of the 18th and 19th centuries was made from tricoloured ribbon to mimic the French Republic flag; 2: A French soldier's cap from the 19th century, known as a “shako”, sporting a cockade; 3: Next, we see the original Cockade worn by French military aircraft during the early part of the First World War; 4: Finally, the British, who originally used a Union Flag on the fuselages and wings of their military aircraft, decided to copy the French, but reverse the order of the colours. It was thought that the St. George's Cross in the middle of the Union Flag or “Jack”, was being misidentified as a German Iron Cross, then in use as an identifier of the enemy's aircraft. Coming in line with an ally's, and not an opponent's, markings was thought to be wise.

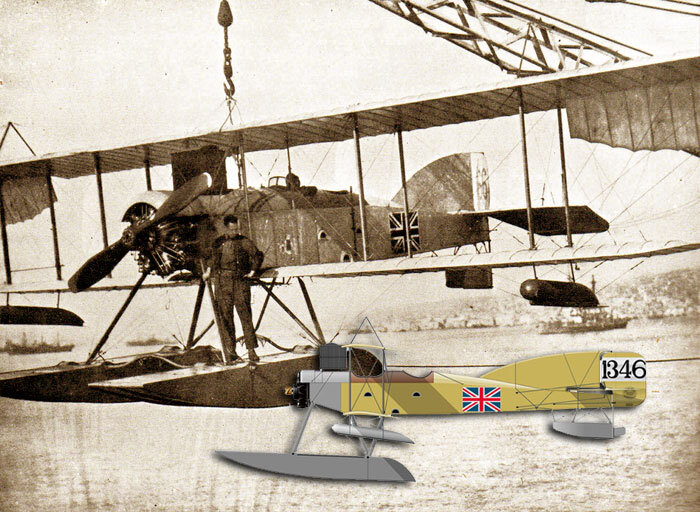

A Short Admiralty Type 630 reconnaissance/torpedo aircraft is hoisted from a seaplane tender in 1915, wearing the original device for identifying aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service – the tri-coloured Union Flag. It wasn't long before this was replaced by the red, white and blue cockade or roundel. Inset: A profile illustration of a similar radial-engined Short 184 showing how the original RAF and RNAS identification device might have looked. The aircraft depicted here would have operated from Naval Air Station Great Yarmouth in the summer of 1915. Photo via Steven Bradley, illustration via Mikhail Bykov @ Wings Palette

Related Stories

Click on image

There was a short period immediately after the adoption of the French-style cockade to identify Royal Flying Corps aircraft, when both devices were employed – in the case of this recently downed Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c of 12 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, it was roundels on the fuselage and Union Jacks under the wings. This photograph of German officers posing with their trophy was taken near Phalempin, in northern France, 26 September 1915. The aircraft was later made airworthy again and given German markings, thus adding to the confusion. Image via Brett “Drake” Goodman's Flickr site

During the First World War, the Royal Flying Corps adopted and adapted the French Flying Service cockade as an identifier. Obviously, no colour photos of its use exist, but this photo taken by one of the world's best and most well-known air-to-air (A2A) photographers, Gavin Conroy of New Zealand, shows us just how it would have looked on this SE5a from Peter Jackson's The Vintage Aviator Co. The centre red circle is much smaller relative to the other rings compared to later RAF roundels of the Second World War. Photo: Gavin Conroy

The roundel would undergo many changes before, during, and after the Second World War, all of which have caused much confusion in the minds of the uninitiated. By the end of the war, there were nearly a dozen official variations of the Royal Air Force roundel, and even variations of each of these. Most roundels were painted on at the factory where the aircraft was built, but they were not always executed to the most recent standards. Some roundels were applied as pre-made decals at the factory, while, after repairs in the field, other roundels were applied by hand and could have spurious diameter ratios or even additional outlines. There was an official drafted standard for roundel application, describing the type of roundel, its diameter and its exact position on the fuselage and wings for each aircraft type, but the exigencies of an air force at war caused many a roundel to be applied with only a nod to the rules. Roundel sizes are hard to understand. Some fighters had huge Type A-1 roundels wrapping the fuselage, while others in the Southeast Asia had tiny SEAC roundels applied. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Then, of course, there is the issue of colours. Before the war, the roundel colours were of a significantly brighter hue than those employed during the war. These brighter colours were known as Identification Red and Identification Blue. As the possibility of hostilities approached, the two colours were made more dull and therefore less visible. The new colours were called Identification Red Dull and Identification Blue Dull. For the purposes of simplicity, we will look at all roundels in the brighter of the hues.

After a certain point in the roundel's development during the war, every roundel used on the fuselage was accompanied by a policy specified fin flash on the tail. This makes the discussion far too onerous, so throughout this article, I will only make mention of that complexity now and then... thank God.

Though there are several, slightly varying, versions of each roundel type, we will endeavour in this article to identify the main types of roundels, speak to the reasoning and history behind them and, where possible, to supply actual colour photographs of these roundel types on RAF and Commonwealth air forces aircraft during the Second World War and RCAF aircraft after the war. To do this, I have utilized the amazing collection of colour photography gallery amassed by Belgian historian Etienne du Plessis – nearly 500 rare colour images of the RAF during the Second World War. These will help us understand the seemingly complex world of the roundel. I hope.

The Type A roundel is essentially the same roundel or cockade that has come down through history, with variations, since the First World War. It can be found on the RAF home page today with minor changes to the proportions first delineated long before the Second World War, or even the formation of the RAF. Today, the RAF roundel is called the Type D. The modern Type D roundel has a diameter ratio of 1:2:3 for the red, white and blue circles, whereas the Second World War Type A roundel of the RAF, RCAF, RAAF and RNZAF, as seen above, had a ratio of 1:3:5. During and since the First World War, the ratio of red and blue to white almost seems to be up to the manufacturer, unit or even the painter, but all were at least trying to adhere to standards.

By the beginning of the Second World War, on 3 September 1939, RAF roundel sizes started to show more conformity. On 30 October, all commands were ordered to change upper wing surface Type A roundels to Type B (see below). Initially, all roundels were to be removed from beneath the wings, but for the sake of identification, further instructions ordered all but fighters and night bombers to have Type A under the wing tips. It wasn't long before it was clear that a Type A roundel's outer blue ring was not clearly enough defined against a dark green/brown camouflage fuselage and an outer yellow ring was painted to delineate the edge. By the beginning of the war, Type A roundels were mostly seen on surfaces upon which they would “pop”, such as the bright yellow paint of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) trainers. Type A roundels faded from fuselage use early in the war, but lingered on the undersides of some aircraft.

The roundel was not only used on aircraft, though that was its initial purpose. It was used in literature, on the RAF and RCAF ensign and, from time to time, to identify RAF vehicles. In an ironic twist, the roundel, which was first created to mitigate friendly fire on aircraft from ground forces, is now used to help prevent the opposite – to identify RAF support vehicles and structures to marauding RAF fighters and fighter/bombers. Here an RAF lorry, displaying a big Type A roundel on its bonnet, is gassed up somewhere in North Africa. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Type A roundel was widely used on the yellow training aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan such as this de Havilland Tiger Moth, which first saw service at No.1 Elementary Flying Training School at Malton, Ontario, starting at the beginning of February 1941. By the end of 1942, this Tiger Moth was training pilots at No. 20 Elementary Flying Training School at Oshawa, Ontario. This photograph was taken either at Malton or nearby Oshawa. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Type A roundel, used by the RAF and its progenitor, the Royal Flying Corps from 1915 to 1940, was also approved for use on camouflaged backgrounds in the Second World War, but only from 1939 to 1941. Other than photos of training aircraft of the BCATP, it is more difficult to find colour images dating from that two-year period that show Type A roundels on camouflaged aircraft. This Anson I sports early-war Type As on its fuselage and upper wing surfaces, but has no tri-colour fin flash. Here we can easily see the lack of definition that a Type A roundel offers on a dark camouflage background.

At the start of the Second World War, there were 26 RAF squadrons operating the Anson I: 10 with Coastal Command and 16 with Bomber Command. However, by this time, the Anson was obsolete in the roles of bombing and coastal patrol and was being superseded by the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley (soon to be obsolete as well) and Lockheed Hudson. This Avro Anson Mk I (ex RAF R3535, RCAF serial 6054) was originally manufactured in England, but was shipped to No. 1 Training Command at Camp Borden, Ontario, in May 1940. Likely, it was there that its original operational camouflage was painted over with the bright yellow training scheme patches. After being prepped for her new, and more appropriate, training role, she flew to No. 2 Air Observers School at Edmonton, Alberta in July 1940 where she became a Navigation Trainer. As this image is over water, we wonder if this was shortly after her new paint scheme at Camp Borden which was near Lake Simcoe, Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. The landing gear, which is normally retractable, is down in this shot but this is understandable. To retract and lower the gear on early model Ansons, the pilot had to make 140 turns on a hand crank. To forgo this laborious process, these Ansons often made short flights with the landing gear extended at the expense of 30 mph (50 km/h) of cruise speed. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Near the end of the First World War, the Royal Flying Corps, a division of the British Army, and the Royal Naval Air Service, a division of the Royal Navy, were joined to form the Royal Air Force. Six years later, in 1924, the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) was created as a unit of the Royal Air Force to service Royal Navy requirements. At that time, the Royal Air Force was operating the aircraft embarked on RN ships. The Fleet Air Arm did not come under the direct control of the Admiralty until mid-1939. During the Second World War, the Fleet Air Arm operated both aircraft on ships and land-based aircraft that defended the Royal Navy's shore establishments and facilities. Royal Navy FAA aircraft, such as this Fairey Swordfish, did triple duties – flying from aircraft carriers, land bases and, in this case, from seaplane bases. Given the Royal Air Force heritage of the Fleet Air Arm, the Royal Navy maintained the use of the now very British RAF Roundel, similar to the Type A. The fact that there is a fin flash on this Stringbag indicates that the photo dates after 1940, though many pre-war Swordfish had the Type A. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A National Steel Car–built Lysander, employed as a gunnery target-towing aircraft in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The BCATP, as mentioned, used the Type A roundel widely, as it was well defined against yellow. The strange yellow and black paint scheme employed by most BCATP “Lizzie” and Fairey Battle target tugs was called the “Oxydol scheme” by many, for its resemblance to the box packaging of a common laundry soap of the same name (see insert). Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Type A roundel was most often used on combat aircraft only on the undersides of the wings, such as on this Canadian Car and Foundry–built Hawker Hurricane XII. The Hurricane XII is usually identified quickly by the lack of nose spinner. Hurricane 5478 flew with 130 Squadron and later with 129 Squadron RCAF, both with the Eastern Air Command. Then it served with the Hurricane OTU at Bagotville, Québec at the end of the war. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Not all training aircraft of the BCATP were painted all yellow. Some, like this Jarvis, Ontario-based Fairey Battle gunnery trainer, began their careers as operational combat aircraft. The Battle was powered by the same Rolls-Royce Merlin piston engine that gave contemporary British fighters high performance. However, the Battle was weighed down with a three-man crew and a bomb load. Despite being a great improvement on the aircraft that preceded it, by the time it saw action it was slow, limited in range, and highly vulnerable to both anti-aircraft fire and fighters with its single defensive .303 machine gun. During the "Phoney War", the Fairey Battle recorded the first RAF aerial victory of the Second World War but, by May 1940, it was suffering heavy losses of well over 50 % per mission. By the end of 1940, the Battle had been withdrawn from combat service and relegated to training units overseas.

This one still sports the original camouflage, which has been overpainted with a Type A roundel. The Battles normally wore a Type A-1 roundel which had a thick yellow outer band. The remnants of this Royal Air Force Type A-1 roundel can be seen beneath the white fuselage flash. This is Fairey Battle Mk. I (RCAF 1604 and ex RAF N2158), brought on RCAF strength 24 February 1940 and struck off charge 27 October 1942 after a crash on 18 August 1942 while serving with No.1 Bombing & Gunnery School at Jarvis, Ontario. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

What appear to be freshly delivered Vultee Vengeance aircraft line a dirt ramp somewhere in the Far East (India, Burma), sporting Type-A roundels. When Type A roundels were employed, the standard for fin flashes was to have red, white and blue bars, all of the same thickness. The Vultee A-31 Vengeance was an American dive bomber of the Second World War, built by Vultee Aircraft. The Vengeance was not used in combat by the United States. It did see combat, however, with the Royal Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force, and the Indian Air Force in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Almost all images of Type A roundel usage are from the early part of the war. The problem is, there was very little usage of colour film at that time. Here we see a flight of three Supermarine Spitfire Mk Is of 19 Squadron RAF on a patrol over the English Channel in the summer, wearing early-war Type A roundels on their fuselages, and the ubiquitous Type Bs on the upper surfaces of their wings. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Prior to the increased hostilities leading up to the Second World War, bomber and fighter aircraft were painted considerably brighter colours, left bare metal or, as in the case of this Hawker Hind owned by the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, a combination of both. The Type A or classic roundel was painted on all six surfaces of such aircraft. Photo: Peter Handley

All of our BCATP aircraft are painted in yellow with roundels of the accepted Type A design. Here, Mike Potter and Dave O'Malley work on the new markings scheme for the Harvard IV. Aware that there were no Harvard IVs in use with the BCATP during the Second World War, we still chose to mark her as a Harvard II of No. 2 Service Flying Training School, Uplands. This particular set of markings is identical to that found on a photo of RCAF Harvard 2866, one of 12 Uplands-based Harvards that appear on the log book of John Gillespie Magee, poet of High Flight fame. Photo: Peter Handley

The Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Harvard, or High Flight Harvard, thunders overhead. She sports Type A roundels on her underwing surfaces and fuselage, but carries roundels of the Type B style on top of her wings. Photo: Peter Handley

The roundel was not only used on aircraft, though that was its initial purpose. It was used in literature, on the RAF and RCAF ensign and, from time to time, to identify RAF vehicles. In an ironic twist, the roundel, which was first created to mitigate friendly fire on aircraft from ground forces, is now used to help prevent the opposite – to identify RAF support vehicles and structures to marauding RAF fighters and fighter/bombers. Here an RAF lorry, displaying a big Type A roundel on its bonnet, is gassed up somewhere in North Africa. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Type A-1 roundel is essentially a Type A with an additional thick outer ring of bright yellow to allow the roundel to be more visible against a darkly camouflaged wing or fuselage. The three interior rings of this roundel maintain the same ratio of thickness as the Type A roundel, giving the proportions a diameter ratio of 1:3:5:7. This roundel was mandated for use on all camouflaged surfaces from 1937 until March 1939 and then just on fuselage sides from 1940 to 1942, until even these were superseded by the Type C-1 in July 1942. It is very rare to find a photograph of a Type A-1 roundel used on the top side of wings, but very common indeed to see it on the fuselages of aircraft during the first half of the war.

Given the amount of contrasting colours (yellow and white), some night bombers had the white ring painted out black or blue to reduce visibility to enemy night fighter pilots. Later, it was decided that the yellow ring was far too visible by day or night, and an effort was made to reduce the amount of yellow resulting in the Type A-2 roundel. This roundel was further reduced in visibility shortly after that when the white ring was reduced by half, giving us the Type C roundels. But I am getting ahead of myself... here, for your edification are a few colour photos showing Type A-1 roundels in action.

Previously, we showed you a photo of a Fairey Battle gunnery trainer with a Type A roundel applied post-delivery to the BCATP. That aircraft, like this Battle, was delivered with a Type A-1 roundel, fresh from a failed combat career during the “Phoney War”. The roundel's outer yellow ring allowed it to be more easily seen against a dark camouflage paint scheme. We can also see the bright yellow visibility patches on the top of the wings. More important in this image than the roundel or the aircraft that bears it, is the man standing on the wing – he is famous Warner Bros. contract actor James Cagney, who was the lead in the now-famous film called Captains of the Clouds. The film was a concoction of the promoters of the BCATP and Warner Bros. to promote the “Plan” and get support from the US and even pilot and aircrew recruits. Unfortunately for the film, which was Warner Bros.' biggest budget production to date, the Japanese made their attack on Pearl Harbor about the same time as the film premiered in New York. With America in its own world war tailspin, there was little interest in a film about Canadian bush pilots trying to get into the war. Image via Warner Bros.

Roundels were initially painted on in the factory where the aircraft was constructed. This factory fresh Lockheed Hudson has just been completed in California to the specifications of the Royal Air Force, which asked for the Type A-1 roundel on its camouflaged flanks. Here, it is photographed in the United States before delivery overseas. From Burbank, California, these aircraft made their way to Gander, Newfoundland, flown by civilian Ferry Command pilots. From there, they flew on to Greenland, Iceland and eventually Scotland. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Ground crew assist a 222 Squadron Spitfire Vb pilot preparing for his next sortie at RAF North Weald. Aft of him is a large Type A-1 roundel, where we can see the proportions are slightly off what was originally intended as the red centre is slightly too large. The original design called for the centre red circle to be one unit wide, the white 3 units, the blue 5 units and the yellow 7 units. The Type A-1 was used on ALL camouflaged surfaces from 1937 to March 1939 and then just on fuselage sides from 1939 to its service-wide replacement by the type C-1 roundel in July 1942. On some night bombers, the white was overpainted with black to reduce visibility.

On 5 October 1939, No. 222 Squadron was reformed at RAF Duxford, flying Blenheims in the shipping protection role, but in March of the following year it re-equipped with Spitfires and became a day-fighter unit. It fought during the Battle of Britain, being based at RAF Hornchurch on 15 September 1940, under Squadron Leader "Johnnie" Hill. It later took part in Operation Jubilee, the 1942 Dieppe raid. In December 1944, the squadron converted to Tempests, which it flew till the squadron was called back to the UK to re-equip with Meteors. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

This shot of a 135 Squadron, RCAF Hurricane XII shows us a properly-proportioned Type A-1 roundel as well as the squadron's Fighting Bulldog emblem on the nose. Like most fighters and even some training aircraft of the BCATP, the Hurricane in the foreground, and 5405, sport Type B roundels on their upper wing surfaces. The Type B was used ubiquitously on the upper wing surfaces of operational aircraft as it was, with the elimination of the white circle, less visible to marauding enemy aircraft. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The effect of the large amount of yellow and white in the Type A-1 roundel was an increased visibility to the enemy – particularly at night. Some night bombing units with Type A-1 roundels chose to paint over the white and even the yellow rings to reduce visibility. Painting out the white on this obsolete Armstrong Whitforth Whitley bomber's Type A-1 roundel did not help her 78 Squadron crew very much for, on the night of 16–17 August 1941, it was lost on operations from its base at RAF Middleton St. George in Durham. The Armstrong Whitworth A.W. 38 Whitley was one of three British twin-engine, front line, medium bomber types in service with the Royal Air Force at the outbreak of the Second World War (the others were the Vickers Wellington and the Handley Page Hampden). As the oldest of the three bombers, the Whitley was obsolete by the start of the war, yet over 1,000 more were produced before a suitable replacement was found. A particular problem with the twin-engine aircraft was that it could not maintain altitude on one engine. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Of course, the Vintage Wings of Canada aircraft are the best machines on which to view your favourite roundels. Here our 6 Squadron Flight Lieutenant Bunny McLarty Hawker Hurricane IV shows off her perfectly proportioned Type A-1 roundels on her fuselage and Type Bs on the wings. Photo: Eric Dumigan

The Type A-2 roundel was an alternative ratio roundel used on some early Second World War aircraft, including Grumman Martlets purchased from the United States. The diameter ratio of ring sizes for the Type A-2 was 1:3:5:6. The idea of the Type A-2 roundel was to reduce the amount of yellow in the outer ring to reduce its overall visibility. The smaller outer yellow ring still had the benefit of delineating the roundel against the dark camouflage, but reduced its high visibility signature. Having searched both Etienne du Plessis' marvelous Flickr gallery of colour photographs of the RAF during the Second World War, as well as the web in general, it became obvious from the dearth of colour photographic evidence, that the Type A-2 was either infrequently used or was quickly superseded by the more commonly utilized Type C-2 roundel (see below).

The Type A-2 roundel is one of hardest to find roundel types used during the Second World War. Finding colour photos of it in use was difficult. Here, an RAF Vickers Wellington bombs up somewhere in England early in the war, wearing a perfect example of the Type A-2 roundel. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A Fairey Swordfish gunner poses with his gas-powered Vickers VGO Gun for a propaganda photographer. On the fuselage of this apparently desert camouflaged “Stringbag” we see a hard-to-find Type A-2 roundel. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

This Royal Navy Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat seems to have a Type A-2 roundel, but the proportions are wrong, so it is possible that this is a botched Type C-1 roundel. Likely this is a pre-delivery photograph taken in the United States and the “Cat” is painted in colours that are “factory-close”, but not official RN paints. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Here we see the same squadron with two different roundel types on the fuselages of their Douglas DB-7B Boston III medium bombers. The Boston in the foreground wears a relatively rare Type A-2 roundel while the next on the flight line sports a much more commonly applied C-2 roundel. Both have matching fin flashes for the roundels applied. The third and fourth Bostons also appear to have a Type A-2, but it may just be the resolution of this image that makes it appear so. This is 88 Squadron, as indicated by the two-letter RH squadron code on the fuselages of these aircraft, seen at RAF Attlebridge in Norfolk. Each squadron in the RAF, and its sister Commonwealth squadrons like the RCAF, carried a two-letter (sometimes a letter and a numeral) identification code on the fuselages of their aircraft, accompanied by a single letter assigned to that particular aircraft. This allowed aircraft without functioning communication to identify their squadrons and squadron mates, for aircraft identification in radio-silence situations or as identities used in after-action reporting. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Type B roundel is, in fact, an early attempt at reducing the visibility of an identifier which, by virtue of its purpose, was designed to be highly visible – a strange paradox. It is essentially what we, today, would call a “low viz” variant of a bold symbol. By removing the white secondary ring and outer yellow ring from the Type A-1 roundel, the contrast was removed. When applied to the top surfaces of wings, the elimination of a bright white made it less visible to marauding enemy fighters from above. The diameter ratio of red to blue was a simple 2:5.

The origins of the Type B roundel go all the way back to the last year of the First World War, when something similar was used on the top surfaces of British bombers employed in night bombing. It was not known as the Type B in this early application, but simply as the “Night Roundel”. From 1923, until phased out a few years later, it was also used on all surfaces of NIVO-coloured night bombers. NIVO was Night Invisible Varnish Orfordness, which was a dark green colour specifically formulated for use on the RAF's heavy biplane night bombers. The Type B was brought back into use in 1938 on camouflaged aircraft in all positions from summer 1938 until superseded shortly after by Type A-1 roundels.

The Type B roundel remained in extensive use on the upper surfaces of many aircraft until 1947. It was commonly used on fuselage sides and upper wings of overall PRU Blue (Photo Reconnaissance Unit Blue – sometimes called Robin's Egg Blue) photo-reconnaissance aircraft from 1940 to 1944 (e.g. photo-reconnaissance Spitfires) and aircraft with "High altitude" camouflage (e.g. de Havilland Hornet) from 1944–1947. As war loomed, the RAF began to paint all their aircraft in dark green/brown or green/grey camouflages on the fuselages and top sides. Overall use of the Type B roundel was found to cause identification problems, and that practice was discontinued in favour of Type A-1, Type A-2, and later, Type C-2 roundels for better visibility on the fuselages. The application of Type B roundels on the upper wings was a common practice right to the end of the war.

When the Type B roundel was used on the upper surfaces to reduce visibility from above, why, then, did the bottom surfaces generally carry roundels (Type A or Type C) that maintained the white? This can be explained by going back to the original purpose of the roundel, which was mainly to stop ground troops from firing on friendly aircraft. Generally (but not always) pilots and gunners were trained enough to distinguish friend from foe. Not so the foot soldier or anti-aircraft artilleryman. Looking up at an overflying aircraft from the ground, even on a grey cloudy day, would still produce a glare effect, reducing the aircraft to a silhouette. By maintaining the white circle, and its better contrast, in the roundels on the underside of wings, the device stood a better chance of being seen by ground forces.

A Fairey Battle warms up – possibly with No. 3 Squadron at RAF Biggin Hill. This one wears the Type B roundel on her fuselage as well as on her upper wing surfaces. The assumption is that the Type B is on all six surfaces as originally specified when the Type B first came into use with the RAF. This Battle was employed to help pilots with the conversion from Gloster Gladiators (seen here in the background) to Hawker Hurricanes in May 1939. The Battle would soon demonstrate its exceptionally inferior fighting capabilities in the Battle of France, and be relegated to training roles in Canada. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A Royal Navy Grumman Avenger shows us clearly that the Royal Navy followed the Royal Air Force Standards for roundel ratios and sizes. This Avenger carries large Type B roundels on her upper wing surfaces as well as later war Type C-1 roundels on her sides. We can see here how taking out the white ring on the standard roundel makes it less visible to enemies looking down from above. Over a thousand Avengers flew in the service of the Royal Navy during and after the Second World War. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

In this pre-war shot of Lysanders from 16 Squadron RAF, we see the use of the Type B roundel on the fuselage sides without the use of a fin flash. I can't be certain, but the top wing surfaces seem to have a rare variant of the Type B roundel called the Type B-1, which included a thick outer band of yellow – rare indeed, as it was used only on “some” aircraft between March and December of 1939. The whole point of the Type B was to get rid of all contrasting colour, so adding the yellow band simply defeated that purpose. Given that 16 Squadron, in 1938, was the first unit of the RAF to equip with the new, and soon to be obsolete, Lysander army cooperation aircraft, and the fact that these ships appear to be brand new, it is likely this shot was taken at RAF Old Sarum, the unit's home base prior to the Second World War. 16 Squadron brought their Lysanders across the English Channel and, following the German invasion of France and the low countries on 10 May 1940, they were put into action as spotters and light bombers. In spite of occasional victories against German aircraft, they made very easy targets for the Luftwaffe, even when escorted by Hurricanes. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Another early example of overall usage of Type B roundels, sans fin flash, on combat aircraft – a pair of 3 Squadron Hawker Hurricane Mk Is in late 1939–1940, possibly at RAF Biggin Hill. These early mark Hurries had two bladed wooden propellers. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Right to the end of the Second World War, the Type B roundel remained in service on the upper surfaces of many wings. Rarely, by then, was it employed as it was intended at the time of its introduction – that is on all six surfaces of an airplane. One of the few exceptions was its overall application on certain recce aircraft painted overall PRU blue, such as this Supermarine Spitfire P.R. XI, photographed in Pomigliano, Italy on 7 March 1944. Photo: Tailhook Ass. via Mark Aldrich and Etienne du Plessis

There is often a difference between the upper and lower surface wing roundel types on BCATP aircraft, but very rarely would your see something like this – a Type B roundel on the top of the port wing and a Type A roundel on the starboard wing of the Harvard II parked just outside the hangar door. This is probably because the Harvard had a wing replacement after an accident or major mechanical issue. Both Type A roundels and Type B roundels were common on the upper surfaces of Harvards of the BCATP, but the bottoms always carried the Type A – as witnessed by the Harvard in the distance. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Not everyone got the official RAF roundel application memo. This shot of a Spitfire being attacked from the rear was an image produced by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry to show a hapless RAF pilot about to meet his doom at the hands of a superior Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf-109 pilot. In fact, this was a captured Spitfire repainted by the Nazis and photographed over the town of Mirow near Rechlin, Germany. The Type B roundel on brown green camouflage was incorrect, but the dead giveaway is the tri-colour fin flash. On all RAF aircraft, the colours would be reversed – red at the front, blue at the back. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

These four Seafire Mk Ibs give you probably one of the best views you could have of a Type B roundel in action. Peeling off in a quick-succession left break from echelon in May of 1943, the four show us how the Type B is visible, yet not overly so, as it would have been with the added white ring. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The exigencies of a fighter squadron on the edge of war – here a 41 Squadron Spitfire (squadron code PN) at RAF Catterick, Yorkshire, sports an improper interpretation of a Type B roundel. This is a perfect example, however, of the improvised toning-down of markings during the period known as the Munich Crisis. Though Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from Munich, after the Nazis had invaded Czechoslovakia, waving a piece of paper signed by Hitler and declaring he had "Peace in our Time", the RAF was taking no chances. RAF roundels were seen in a variety of non-standard proportions at this time, resulting from the hasty painting-out of yellow and white rings to make the roundel less visible. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Unlike the Type A-1 roundels, the Type B roundel had a resurgence in the 1970s to the 80s with middle generation RAF jet aircraft like the Avro Vulcan. Originally the Vulcan prototypes were overall anti-flash white and early models went into service wearing an overall silver paint. Eventually, in the mid-1970s, Vulcan B.2s received a medium sea grey/olive green matte camouflage with light grey undersides and "low-visibility" roundels. These were no longer called Type B roundels as the proportions were different, there being a larger red disc proportionally with a ratio of 1:2, red to blue. This Vulcan is a gate guard at Goose bay, Labrador. Photo: AHunt at Wikipedia

A Sepecat Jaguar GR3 drinking from a drogue and basket refuelling arrangement. She carries a later generation Type B roundel, which was simply called the Low-Visibility roundel, still in use today, but with toned down colours. Photo via Wikipedia

The Type C roundel was a later development of the basic, or classic, Type A roundel. In order to reduce the conspicuousness of the old cockade roundel, the width of the white stripe, almost equal to the other colours in the Type A, is reduced on the Type C, introduced from May 1942. The standard application of this Type C scheme consists in the Type B on the upper surfaces, the Type C on the under surfaces, and the Type C-1 on the fuselage sides, and an accompanying Type C fin flash on the tail.

Type C roundels, essentially an altered Type A, were, as in the case of the Type A, rarely employed on the fuselage sides of aircraft unless these aircraft were also BCATP yellow, PR blue or any light colour. The diameter ratio was a much altered 3:4:8. Since most operational aircraft were of the dark camouflage variety, one rarely sees the Type C on the flanks of a camo aircraft. By the end of the war the Type C roundel and even the Type C-1 are seen in a much bigger size on the upper surfaces of aircraft until 1947, when the Type D roundel was introduced. After the war the RCAF went to a uniquely Canadian roundel featuring the maple leaf. The RCAF did not adopt the Type D roundel, so it is outside of this discussion.

Again, the Type C roundel is hard to find used on the fuselage sides of aircraft. It is normally used on the undersides of wings and combined with a yellow ringed Type C-1 roundel on the fuselage. It is however found on training aircraft as a replacement for the Type A roundel used in earlier aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). This looks to be an Avro Anson trainer and the foothills and mountains in the background give us a clue that this may be an Alberta BCATP base. It is interesting to note that, when the RAF reduced the amount of white in the roundel by increasing the red and blue areas, they did the same with the tri-colour fin flash on the tail. Whenever a Type C or Type A roundel is used, one always finds a fin flash that matches the roundel's proportions and colours. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

This all-metal Handley Page Halifax wears massive Type C roundels on her upper wing surfaces (and more than likely under) as well as Type C-1 roundels on her flanks. After the war, many bombers including this Halifax CV II were adapted to carry freight and passengers for the Royal Air Force. The unarmed Mk CV II transport carried an 8,000 lb capacity cargo pannier instead of a bomb bay, and had space for 11 passengers in the fuselage. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Though many, and possibly most, PRU blue aircraft utilized the Type B roundel on all surfaces, this recce Mosquito has Type C roundels on her flanks, though the usual Type B roundels on her wings. This photograph of Mosquito PR MM364 was taken at RAF Mount Farm, Oxfordshire, when the aircraft was handed over to the USAAF. RAF Mount Farm was originally a satellite airfield for the RAF Photographic Reconnaissance Unit at RAF Benson. The airfield became associated with the United States Army Air Force when, in February 1943, it was used by the Eighth Air Force as a photo reconnaissance station. Mount Farm was given USAAF designation Station 234. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Most instances of Type C roundels used on the fuselage are cases of a light coloured background – bare metal, training yellow, aluminium paint or photo recce blue. Here a de Havilland Sea Hornet F. Mk20 (TT202), painted in high altitude colours, sports Type C roundels all-over (another photo I ran into shows the underside of the wings with Type Cs). The de Havilland DH.103 Hornet was a piston-engined fighter that further exploited the wooden construction techniques pioneered by de Havilland's classic Mosquito. Entering service at the end of the Second World War, the Hornet equipped postwar RAF Fighter Command day fighter units in the UK and was later used successfully as a strike fighter in Malaya. The Sea Hornet was a carrier-capable version with folding wings. We can just make out the joint between the main wing and the folding outer panel, just inboard of the roundels. Photo via kevsaviationpics.blogspot.ca

A bold display of Type C roundels on the upper wing surfaces of a massive Blackburn Firebrand, a torpedo-carrying strike fighter which went into Royal Navy service in 1945, with not much impact on the war. Though it had a powerful look and an even more powerful name, many people consider the Firebrand a failure as an effective combat aircraft. The Blackburn Firebrand was born out of a 1939 specification calling for a two-seat, inline-engined fleet fighter. When it finally entered Royal Navy operational service in September 1945, it was in the form of a single seat, radial-engined torpedo-bomber/fighter. The Firebrand was originally designed as a carrier fighter powered by a Napier Sabre engine, but because of engine unreliability and poor handling it was unacceptable. It was then redesigned to become a fast strike aircraft carrying a large torpedo, and powered by a Bristol Centaurus radial. Its powerful Bristol Centaurus engine and thirteen-foot diameter propeller produced extreme torque swing on takeoff, which could only be countered by the abnormally large vertical tail fin and rudder. The Firebrand was also very difficult to deck land, since the pilot sat closer to the tail than the nose, with predictably poor visibility. While many of its pilots appreciated the fact that the aircraft was built like a battleship, particularly during landing accidents, they did not care for its bulky weight. Finally, the Naval Staff's concept of a torpedo-bomber/fighter combination to which the aircraft was designed was just too much of a compromise, with the end result that the Firebrand was never successful in either role. Still, it had a relatively long service life for the times, from 1945 to 1953, when it was replaced by the quirky, but cool-looking Westland Wyvern. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

It was hard to find images of combat or operational aircraft displaying a basic Type C roundel on their fuselages. A rare exception is this Taylorcraft Auster AOP. The Taylorcraft Auster was a British military liaison and observation aircraft produced by the Taylorcraft Aeroplanes (England) Limited company during the Second World War. The Auster was a twice-removed development of an American Taylorcraft–designed civilian aircraft, the Model A. The Model A had to be redesigned in Britain to meet more stringent Civil Aviation standards and was named the Taylorcraft Plus C. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

By adding a thinner yellow outer ring to the basic Type C roundel, the RAF made the roundel clearer against the camouflaged backgrounds and changed the diameter ratio to 3:4:8:9. This is the most ubiquitous fuselage roundel of the later part of the war, used on aircraft sides from May 1942. Towards the end of the Second World War, very large Type C-1 roundels could be found on the topside of fighter aircraft. A perfect example of this late war topside application can be found in the Flight Lieutenant William Harper Supermarine Spitfire belonging to Vintage Wings of Canada.

The Type C-1 roundel applied to the fuselages of three aircraft of the Empire Central Flying School – a Hawker Hurricane I and two Supermarine Spitfire IIas (note the differences in their propeller spinners). We can also tell in this photo that all the aircraft sport Type B roundels on the upper surfaces of the wings and Type C-1 underneath. Established in April 1942, the Empire Central Flying School (ECFS) was based at RAF Hullavington in the United Kingdom. With flying training taking place on such a vast scale the School worked to maintain and improve flying training standards at the RAF flying schools operating throughout the world. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A Miles Martinet carrying Type C-1 roundels on her sides and Type B roundels on her upper wing surfaces. We can also just make out the yellow and black “Oxydol” striped paint scheme on her undersides – typical of target tugs. The Miles M.25 Martinet was a target tug aircraft of the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm that was in service during the Second World War. It was the first British aircraft to be designed specifically for the role of towing targets. At total of 1,724 were produced between 1942 and 1945. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A good photograph of a Royal Canadian Air Force Hurricane XII (RCAF Serial 5625) sporting a large Type C-1 roundel on her fuselage. Fresh out of the Canadian Car and Foundry (CCF) factory at Fort William, Ontario (now Thunder Bay), Hurricane 5625 was delivered to Number 3 Training Command, and then on to a Home War Establishment squadron. The aircraft survived the war, but languished in a scrapyard in Guelph, Ontario, and was finally sold to Rem Walker of Regina, Saskatchewan, in 1980 to be scavenged. Components of 5625 (as well as two other CCF Hurricanes – 5547 & 5424) were used in the restoration of Hurricane XII 5711. Hurricane 5711, with 5625 DNA, was then sold to B.J.S. Grey of Duxford, UK in December 1982 and shipped from Canada to the Fighter Collection at Duxford, on 9 June 1983. It was registered as G-HURI in Great Britain. This aircraft remains in the Historic Aircraft Collection, though it is presently up for sale. Photo: RCAF

Today, the remnants of the Hurricane in the preceding photo (5625) are contained in Hurricane 5711, displayed by Duxford's Historic Aircraft Collection as HA-C (Z5140) in the colours worn by a Hurricane IIB flown with 126 Squadron during the siege of Malta. This aircraft has been flown by former Vintage Wings of Canada pilot Howard Cook. Recently, the aircraft was put up for auction at Bonhams auction house. The Historic Aircraft Collection hoped that it might fetch £1.7 million – it failed even to make the seller's reserve price. Such is the economy in Europe these days. Photo: HAC

The Royal Navy, the Senior Service, and never one to follow the lead of the Royal Air Force, employed the same identification devices as the younger service – in this case, a Type C-1 roundel on the fuselages of Seafires, the navalized variant of the Spitfire. Here we see Sub Lieutenant H H Salisbury, Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, a fighter pilot of the Fleet Air Arm, adjusting his helmet before a flight at Naval Air Station Yeovilton in 1943. Photo: E. A. Zimmerman, RN via Imperial War Museum and Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A clear shot of a Spitfire Mk Vc from 303 Polish Squadron, RAF carrying Type C roundels under her wings and Type C-1 on her fuselage. No. 303 ("Kościuszko") Polish Fighter Squadron was one of 16 Polish squadrons in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. It was the highest scoring RAF squadron of the Battle of Britain. The name "Kościuszko" comes from the Polish and American Revolutionary hero, General Tadeusz Kościuszko who came to the aid of the Americans. The squadron roots of this name go back to the little known Polish–Russian War of 1919–1921, when pursuit pilots like the legendary Merian Cooper, manned an all-American fighter squadron in the Polish Air Force and helped save Poland (temporarily) from Soviet domination. They were the ones who first chose the name of the famous Pole who took part in the American Revolution for their squadron's title. A Pole helped America, and now Americans were helping Poland – it was a natural fit! Now, in the Second World War, Poles were helping the RAF, which is ironic, since Kościuszko gained fame fighting the British. For a great history of this little known air war, read Kościuszko, We Are Here! by Janusz Cisek. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

The Flight Lieutenant William Harper Supermarine Spitfire Mk XVI, with Vintage Wings founder Mike Potter at the controls, makes a high speed topside pass to show off the large Type C-1 roundels on her upper wing tips as well as her fuselage. Photo: Peter Handley

Not all Type C-1 roundels can be found on aircraft of Second World War vintage. Here we have two Canadian Forces CF-188B Hornet fighters of 410 Squadron flying over the Utah Test and Training Range (USA) for planned engagements during the "Tiger Meet of the Americas" in 2001. Next to the Type C-1 roundel on her sides is the two-letter squadron code “RA”. RA was the squadron designator for 410 Squadron during the Second World War – found on the sides of its Mosquito fighter/bombers. The closest aircraft is painted in a special scheme commemorating the 60th anniversary of 410 Squadron. 410 Squadron's experience during the war included Bolton Paul Defiants, Bristol Beaufighters, and de Havilland Mosquitos. Photo: SSgt. Greg L. Davis, USAF

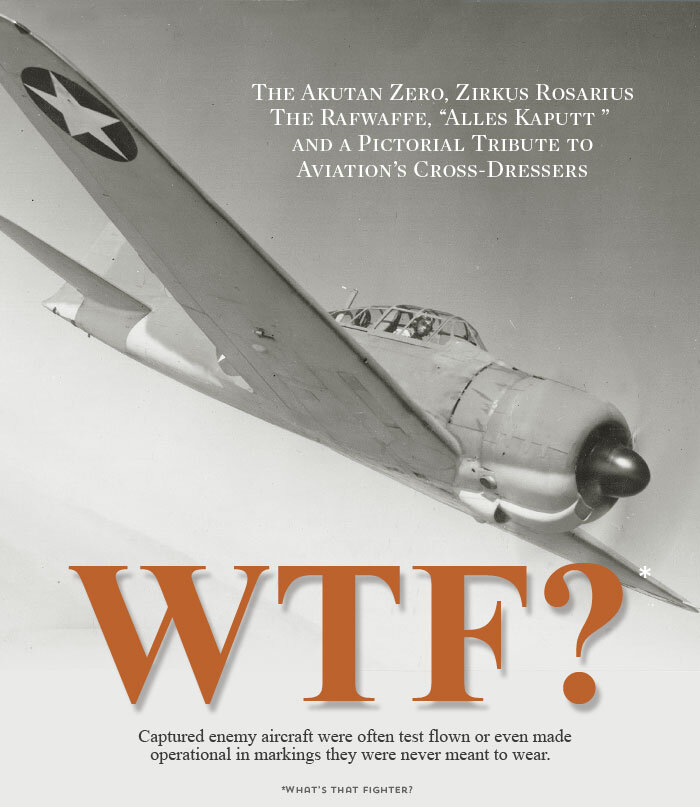

The Type C and type C-1 SEAC roundel was designed specifically for use in combat zones where aircraft were likely to come into contact with aircraft and units of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (phonetically the Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun Kōkūtai) or the Japanese Imperial Navy Air Service (the Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun Koukuu-tai) during the Second World War. Quite simply, this is a basic Type A, Type C or Type C-1 roundel with the red centre removed for a pretty obvious reason – to avoid confusion with the Japanese single red disc roundel called the hinomaru. It was used by units under the South East Asia Command (SEAC) and in the China Burma India (CBI) theatre of operations from 1942. These types of red-removed roundels were not used for very long before being replaced by light blue/dark blue SEAC roundel (see below). Trigger happy pilots, aerial gunners and anti-aircraft gunners, upon seeing red, were likely to shoot first and apologize later.

A blue/white roundel, sometimes with US-style white bars, was also used on Fleet Air Arm aircraft. American-built naval fighters and bombers would come from the factory with white stars and bars on a Shipyard Blue overall paint. The Royal Navy simply overpainted the star with the simple white and blue roundel, omitting the red centre of the British roundel, but keeping the white extending bars of the American insignia. This kept a red circle from appearing in the gun sights of overzealous Allied gunners and added the reassurance of American-style white bars. Some aircraft like FAA Seafires obviously did not arrive from a factory with the bars painted on. They were added to the Seafires and other non-American-built assets for the sake of RN consistency. This was only used in the SEAC. Blue and white roundels were also used by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), which simply overpainted the red dot in white, regardless of previous proportions.

A Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat comes in for a landing somewhere in the Southeast Asia theatre of operations during the Second World War. On her sides we see a yellow-ringed SEAC Type C-1 roundel as well as simple SEAC Type C roundels on her upper wing surfaces. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

An Avro York, a transport adaptation of the legendary Lancaster heavy bomber, awaits VIPs on an Egyptian ramp in 1946. She proudly displays perfect SEAC type roundels and fin flashes. This particular York, nicknamed “Zipper”, was converted to (not built to) VIP standard for use by Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park GCB KBE MC&Bar DFC RAF, as AOC Air Command South East Asia, an appointment he held from February 1945 into 1946. Although “Zipper” was normally based at Singapore which was part of SEAC, this photograph was taken at Almaza, Cairo, Egypt shortly after the war. Sir Keith, a New Zealander by birth, is probably best remembered as Air Officer Commanding No. 11 Group, RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. A permanent bronze statue to Sir Keith was unveiled at Waterloo Place, London, on Battle of Britain Day, 15 September 2010, to mark the 70th Anniversary of the Battle. Sir Keith retired from the RAF in December 1946 and returned to New Zealand where he remained until his death in 1975 at the age of 82. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

I find it interesting that the smallest size of roundels in the entire RAF was routinely applied to aircraft in the SEAC or CBI theatre. On the underside of the port wing (and less visibly on the starboard) we can see tiny SEAC roundels on this P-47 Thunderbolt. The Thunderbolt also wears a common identifier for the region's RAF fighter aircraft – SEAC white stripes on her wings and elevators. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

Obviously a staged photograph of maintenance crews working on a Grumman Avenger of the FAA, while being bombed up, as a group of pilots and aircrew go over plans for an attack on Japanese targets. Forget all that and focus on the large Type SEAC roundel on the top of the folded starboard wing – a SEAC roundel with tiny white aperture. In the field, SEAC roundels were altered to present less visibility when looking down from above over jungle terrain. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A Bristol Beaufighter Mk Ic of 31 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF Serial A19-17) shows us very typical SEAC Type C roundels on her fuselage. The RAAF simply painted out the red dot in the centre of each roundel, and even the red bar of the fin flash. On 30 August 1943, Beaufighter A19-17 was part of a six-plane strike on Taberfane Seaplane Base and shot down a Japanese Mitsubishi FM1 “Pete” seaplane which had just taken off. This same Beaufighter later crashed into the sea on 19 October 1943, while returning from an 8-Beaufighter raid on Trangan Aru Island – the Pilot Flying Officer F.H. Cridland and Navigator Pilot Officer R.B. De Pierres were both killed. Following the attack, against a newly constructed airfield near the Taberfane Seaplane Base, A19-17 was seen to be lagging behind after leaving the target area. Dropping alongside A19-17, the Squadron CO saw De Pierres leaning over the slumped and obviously wounded Cridland, handling the controls. De Pierres was ordered to bail out immediately, and to await rescue by a Catalina, as it was impossible for him to reach the rudder pedals to stop the Beaufighter from entering a spiral dive. The navigator refused to abandon the unconscious Cridland. Soon afterward A19-17's starboard wing dropped, and with one arm around his pilot, De Pierres waved a final farewell. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A group of sailors take five on the wing of a Royal Navy Grumman Hellcat of the Fleet Air Arm on board an aircraft carrier in Southeast Asian waters. Note the blue and white roundel without the usual red centre. This was done to prevent any confusion with the all-red roundel, known as the Hinomaru (literally: circle of the sun) used by Japanese aircraft – nicknamed the “Meatball” by American flyers. This particular roundel has a particularly small central white circle – compare this with the white centre of the roundel on the Beaufighter in the previous photograph. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A P-40N Kittyhawk displays a typical Royal Australian Air Force SEAC roundel on its fuselage as well as the famous all-white empennage of RAAF P-40 squadrons operating from primitive airfields on Papua New Guinea. Like Vintage Wings of Canada's own P-40N, this aircraft was also rescued from the jungles surrounding the old airfield on the coast of Northern Papua New Guinea called Tadji. The Kittyhawk is painted in the markings of a P-40 of 75 Squadron. If the Flying Tigers were the best-known of the P-40 groups of the entire war, No. 75 Squadron of the RAAF has to be ranked as one of the best individual squadrons. While the American Volunteer Group (AVG) was made up of crack pilots with plenty of experience, 75 was hastily thrown together with untrained and inexperienced pilots and thrust into the breech in New Guinea against superior Japanese pilots and planes. Despite being almost wiped out, they held their ground and wrote a special chapter in aerial history. The aircraft wears the nose art “Currawong” and a stylized image of a bird. The Currawong is a Raven-like bird, native to Australia. Photo: Gavin Conroy

Here we see a fine example of the SEAC roundel – with red centre removed, but white USN bars painted over the camouflage of this Royal Navy Seafire. While many American-built carrier-based aircraft of the FAA came with the bars from the factory, this Seafire was altered in theatre. It is seen taxiing at an American B-24 Liberator base somewhere in the Far East. Photo via Etienne du Plessis' Flickr site

A nice lineup of aircraft in New Zealand shows us a history of roundels at a glance. In the foreground, the P-40 wears RAAF SEAC roundels, the Spitfire wears Type Bs on her wings and Type C-1s on her waist, while the postwar Mustang in the number three position sports the modern roundel of the RAF – the Type D (diameter ratio of 1:2:3), which is outside of our RCAF history, as we never adopted that roundel. Photo: Gavin Conroy

The RAF Third Tactical Air Force (Third TAF), which was formed in South Asia in December 1943, was one of three tactical air forces formed by the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and was the air force unit of the South East Asia Command. It was made up of squadrons and personnel from the RAF and the air forces of the British Commonwealth. Third TAF was formed shortly after the establishment of South East Asia Command to provide close air support to the Fourteenth Army.

It was first formed on 19 December 1943, designated the Tactical Air Force (Burma), and renamed as the Third TAF on 28 December 1943. Along with parts of the USAAF Tenth Air Force, it was subordinate to Joint Allied Eastern Air Command which was also formed in December 1943. The official roundel of the SEAC was the elegant dark blue/light blue roundel, which was used by units under South East Asia Command and in the CBI theatre mid-1942–1946. As with earlier SEAC roundels, the red was removed to avoid confusion with the hinomaru. Initially, as in the case of the RAAF units, the red was overpainted with white but this compromised the camouflage and the normal roundel blue was mixed 50:50 with white. Many aircraft in the CBI theatre used roundels and fin flashes of approximately half the normal dimensions, perhaps because the amount of white in the normal sized roundels, when seen against a dark green jungle canopy, was too obvious to the enemy above.

The 436 Squadron C-47 Dakota, Canucks Unlimited, of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, makes a low flypast and shows off her SEAC blue on blue roundels and appropriately proportioned fin flash. 436 Transport Squadron was assembled in Gujrat, India (now in Pakistan), on 9 October 1944. Equipped with the C-47 Dakota, 436 Squadron flew its first official mission on 15 January 1945 from Kanglatongbi, Assam, India, when seven Dakotas airlifted 59 tons of supplies for 33 Corps of the Allied 14th Army in Burma. Soon the adopted emblem and quasi-motto of the squadron, "Canucks Unlimited," would be seen far and wide in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theatre of operations. For more on 436 and 435 Squadrons and the Canucks Unlimited legend, click here. Photo: Gus Carujo

A Battle of Britain Memorial Flight Spitfire PR Mk XI (PS915) displays classic SEAC blue on blue roundels and matching fin flash. As with most SEAC roundel applications, the roundel is considerably smaller than those typically found on European Theatre of Operations (ETO) Spits – less than 50 % ETO size. Today, this aircraft wears PRU blue markings from the end of the war, but it briefly had these SEAC markings commemorating 152 (Hyderabad) Squadron. 152 Squadron moved to Burma on 19 December 1943 and joined the RAF Third Tactical Air Force (TAF). During the Battle of Imphal, the squadron operated from frontline strips and supported the Fourteenth Army during its final conquest of Burma. It was disbanded on 10 March 1946 in Singapore, to where it had moved after the Japanese surrender. Photo: Ian Howat

Though the RCAF had been an independent service for many years, Canada used standard British roundels and fin flashes on all of its aircraft until shortly after the end of the Second World War. The RCAF had distinguished itself on operations around the globe. At its peak during the war, the RCAF had a total of 78 squadrons, including 35 serving overseas, and 215,200 personnel. Of the 43,099 Canadian killed in action during the war, 13,500 served with the RCAF. It was now time for a unique roundel and identity that spoke to the essence of being Canadian. The first design took the serrated silhouette of a leaf from the ubiquitous, and very Canadian, leaf of the Silver Maple and substituted this for the red circle in the centre of the venerable RAF Type B roundel. This would last only a short time as it was not distinct enough from any distance. This then led to the now familiar "Silver Maple" roundel employed by the RCAF for nearly two decades and the “Sugar Maple” roundels found on RCN aircraft for 22 years. On 15 February 1965, a stylized 11 point maple leaf was introduced on the new Canadian flag and this leaf has been the central proud element of all Canadian aircraft roundels to this day. Let's look at the lineage of the modern Canadian roundel.

I looked long and hard on the web for a colour photograph of an RCAF aircraft wearing the first generation RCAF roundel – a simple blue disc with a red maple leaf in the centre. The only decent image I could find was this shot of Vampire 17030, but it was black and white. The use of this roundel was short-lived as, like the RAF's Type B roundel, it was not visible enough for general usage on all types of aircraft and background colours. I have only seen this roundel used on Vampires, Mustangs and Harvards. Any information of its history or colour photographs would be greatly appreciated. Photo: RCAF

Three de Havilland Vampires of the Blue Devils display vintage original RCAF roundels. The Blue Devils or the 410 (F) Squadron Aerobatic Team was a Royal Canadian Air Force aerobatic team that flew the de Havilland Vampire jet aircraft from 1949 to 1951. The unit was the RCAF's first postwar aerobatic team, and belonged to the RCAF's first operational jet fighter squadron, No. 410 Squadron. Photo: RCAF

The Navy generally used roundels similar to those of the Air Force, but in this case, I believe these roundels were applied when the aircraft was with the RCAF. Here we have a rare photo of a Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) Harvard II (S/N 2898) wearing the first postwar roundel of the RCAF as it banks over the RCN dockyards at Halifax. The long-serving Harvard 2898 served during the Second World War at No. 9 SFTS Summerside, Prince Edward Island, No. 31 SFTS Kingston, Ontario, and No. 14 SFTS Aylmer, Ontario. Postwar, the RCAF operated it with an auxiliary squadron at London, Ontario, and at Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. It was loaned to the Royal Canadian Navy in January 1950. It is my guess that she arrived at RCN Shearwater wearing these uniquely RCAF roundels. Photo via the Naval Museum of Manitoba

The first attempt at an all-Canadian roundel was not entirely successful or distinct enough, especially against the all aluminium, or white-topped aircraft of the RCAF in those early postwar years. It was decided to keep the serrated “silver maple” leaf but bring back the white tri-coloured roundel of the RAF known as the Type A. At the end of the Second World War the RAF had a new roundel of its own – the Type D, a modified Type A. Like all roundels in history, the new Silver Maple roundel seemed to be slightly random when it came to proportions, despite all policies. It came in two basic types – one using a small leaf and another, far more common one, employing a larger silver maple leaf silhouette.

A Canadair Sabre, with slats out and nose high, struggles to fly as slow as the aircraft with the photographer, over a Canadian winter landscape. It carries on its side simple new tri-colour roundel of the small leaf variety as well as the old Canadian Red Ensign. Sabre 23757 was one of 390 Canadair CL-13B Sabre Mk. 6 (the last version, with Avro Orenda 14 engines) that served with the RCAF. This Sabre is carrying the camouflage developed for all RCAF European-based operational aircraft. The photo was taken while the aircraft belonged to No. 1 Overseas Ferry Unit (OFU) based at St. Hubert, Québec and formed in 1953 to ferry Sabres and T-33s across the North Atlantic. The motto of the OFU was a humorous bogus Latin one – “Deliverum Non Dunkum.” Photo: RCAF website

The most ubiquitous roundel used after the war up until the introduction of the modern era flag maple leaf roundel, was the classic Big Leaf roundel of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Like the Small Leaf version, it is a silhouette of a silver maple leaf. Canadian pilots and aircrew were justifiably proud of this bold Canadian identity. Canada was the first of the Commonwealth air forces to adapt the old RAF roundel to make a powerful national identity statement. The RCAF was using maple leaf inspired roundels since the late 1940s and were employing this red, white and blue maple roundel before the end of that decade. It was not until 1956 that the Royal Australian Air Force stopped the usage of the standard RAF roundels and adopted the silhouette of a kangaroo to replace the centre red circle. The Royal New Zealand Air Force did not employ the kiwi bird-centred roundel until the end of the 1960s. There is no doubt that the beautiful and proud practice of adapting an RAF roundel with a national symbol silhouette comes from the Royal Canadian Air force.

Three factory-fresh bare metal Canadair Sabres close up formation for the photographer – naked except for their new RCAF classic roundels and a Type C fin flash. The Canadair F-86 Sabre was to become the RCAF's most famous and unanimously well-liked, operational fighter. RCAF Sabre squadrons were a force to be reckoned with in the European skies. Photo: RCAF

Unlike the previous photograph of generic Sabres with no markings to help a viewer tell anything about them, save that they are Canadian, this gorgeous image of the Flight Lieutenant Fern Villeneuve Hawk One Canadair Sabre 5 tells an entirely different story. Painted in the outstanding metallic gold paint of the Golden Hawks air demonstration team of 1951 to 1963, there is no doubt what unit this ship flies with. At Vintage Wings of Canada, we have two aircraft that bear the tri-colour postwar roundels of the RCAF – Hawk One and the Flight Lieutenant “Tim” Timmins de Havilland Chipmunk. In this photograph, we see pilot Chris Hadfield, canopy back and enjoying the day, banking away from the camera and showing us a good view of Hawk One's array of roundels. This month, Hadfield, a Vintage Wings of Canada board member and pilot, will launch from Russia aboard a Soyuz capsule to become the first Canadian to command the International Space Station (ISS). He will spend half a year orbiting the planet. Our other astronaut Sabre pilot, Jeremy Hansen, promises to keep his ejection seat warm for him. Photo: Peter Handley

The dream that became a nightmare – the prototype Avro CF-105 Arrow (RL201) sits proudly on the ramp at Avro's Malton, Ontario, factory ramp wearing the symbol of an air force at its zenith – the Royal Canadian Air Force classic roundel and Type C fin flash. This was a time before Canadian military aircraft wore the Red Ensign flag of Canada or, later, the maple leaf flag we so love today. The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow was a delta-winged interceptor aircraft, designed and built by Avro Aircraft Limited (Canada) as the culmination of a design study that began in 1953. Considered to be both an advanced technical and aerodynamic achievement for the Canadian aviation industry, the CF-105 held the promise of Mach 2 speeds at altitudes exceeding 50,000 ft. (15,000 m), and was intended to serve as the Royal Canadian Air Force's primary interceptor in the 1960s and beyond. Not long after the 1958 start of its flight test program, the development of the Arrow (including its Orenda Iroquois jet engines) was abruptly and controversially halted before the project review had taken place, sparking a long and bitter political debate. The controversy engendered by the cancellation and subsequent destruction of the aircraft in production remains today a topic for debate among historians, political observers and industry pundits. Photo via RCAF website

A Canuck in Canuck markings – classic early RCAF roundels are powerfully displayed on this big Canadian-designed fighter of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Though the CF-105 Arrow (previous photo) brought Avro Canada to its knees, the company was both innovative and successful despite its ultimate demise. The biggest success for the company was the development and manufacture of nearly 700 CF-100 “Canucks” or, as Sabre pilot detractors liked to call them, “Clunks”. The CF-100 Canuck was a Canadian jet interceptor/fighter serving during the Cold War both in NATO bases in Europe and as part of NORAD. The CF-100 was the only Canadian-designed fighter to enter mass production, serving primarily with the RCAF/CAF and in small numbers in the Belgian Air Force. For its day, the CF-100 featured a short takeoff run and high climb rate, making it well suited to its role as an interceptor.

This particular CF-100 (18383) was a Mk. IVB Canuck with 423 Squadron at the time this photo was taken over St. Hubert, Québec. Besides the Mk. IVs remarkable squadron service in Canada and Europe, it made headlines in the English newspapers when it became the first military jet aircraft produced outside England to perform at the Farnborough Air Show in 1955. The aircraft was one of three Mk. IVBs that had been sent to England for evaluation at Boscombe Down Test Establishment. Photo: RCAF website

The Royal Navy followed the lead of the Royal Air Force in the design and application rules regarding roundels on aircraft. So too did the Royal Canadian Navy follow the Royal Canadian Air Force... but not quite. After the RCAF introduced their first red and blue maple leaf roundel, they went through a period of change to create the fully accepted tri-colour Silver Maple leaf silhouette roundel. The RCN felt the need to design and apply its own roundels – distinctly Canadian, as was the RCAF, but simultaneously distinctly Navy. Instead of the silhouette profile of the heavily serrated Silver Maple, they chose instead the simpler silhouette of the Sugar Maple leaf from the tree that gives us the distinctly Canadian treats known as maple sugar and maple syrup. The RCN went one step further and created a relatively smaller white centre on which to place the red leaf, giving the RCN roundel its thicker looking blue ring. Oh, my... now I am really sounding like a geek.

At the beginning of its use, the Sugar Maple roundel of the RCN employed a yellow outer ring, even when the roundel was used against a light grey paint such as many carrier aircraft had in the 1950s. By 1952, this had disappeared. When the Navy was merged with the Air Force and Army, the use of the Sugar Maple roundel disappeared... or had it. In fact, the modern, stylized maple leaf of the new Canadian flag, introduced in 1965, and now a part of the Canadian roundel forevermore, looks more like a stylized sugar maple leaf than a silver maple leaf. It bears a close resemblance to that found at the centre of the RCN roundel... now the Royal Canadian Air Force is wearing the Navy roundel!!!

A Grumman Avenger (S/N 85861 – an AS3 Mk1 Early Variant) from HMCS Magnificent (circa 1950–1952) wears Royal Canadian Navy roundels with yellow outer rings. The difference between the RCAF and the RCN roundels was the thickness of the blue outer ring – the RCN roundels had a definite thicker blue ring and a slightly different red maple leaf. The yellow outer ring was employed on RCN roundels up until 1952. Note the AN/APS-4 radar pod fitted to the underside of the starboard wing. The “-3E” aircraft purchased by the RCN was the last Avenger model to be produced in quantity during the Second World War. The Royal Canadian Navy acquired its aircraft carriers after the Second World War – HMCS Warrior, HMCS Magnificent (Maggie) and HMCS Bonaventure (Bonnie). Prior to this, Royal Canadian Navy pilots and aircrew all flew for the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. In addition, some RCN aviation units were land-based. Photo: RCN

The only jet fighter aircraft to fly for the Royal Canadian Navy was the McDonnell Douglas F2H-3 Banshee. Here, a Banshee banks hard over Halifax harbour and the Angus L. Macdonald Bridge. She wears Royal Canadian Navy roundels, sans outer yellow rings, which were discontinued in 1952. Even this jet aircraft still had the Type C fin flash, when RCAF aircraft were wearing Red Ensigns. The RCN acquired 39 Banshees from 1955 to 1958. Banshees operated from shore bases and from the aircraft carrier HMCS Bonaventure after 1957. The Banshee was the RCN’s last fighter and was not replaced when retired from service in 1962. When the three services were merged into one entity known as the Canadian Forces, it lost all of its flying units to the former RCAF, by then a Command of the CF. Photo: RCAF website

A clear indication of the RCN's desire to be different is seen on the sides of this Piasecki HUP-3 – the RCN's unique roundel and the Navy ensign instead of the National Red Ensign. Three Vertol (Piasecki) Model PD-18 twin rotor helicopters, known to the RCN as HUP-3s, flew with VU-33 Squadron between May 1954 and January 1964. Early versions of the HUP were called the “hupmobile” or “shoe”, because of their distinctive shape. Number 51-16623, seen here, now resides in Ottawa's Canada Aviation and Space Museum. Photo: RCAF

From a simple identifier, designed to stop the wrong people shooting at us, to one of the proudest national symbols extant, the roundel has come a long, long way. Today, the aircraft of the RCAF proudly display the classic modern era roundel on their surfaces, but there was a time when many RCAF members were reluctant to change over from their old roundel.

A DC-3 Dakota of Air Transport Command of the Canadian Armed Forces displays several aircraft identification elements of the Canadian Air Force of the day – classic RCAF lightning bolt “cheatlines”, white-top upper fuselage, red outer wing panels and new roundels mirroring the new Canadian Flag. The title “Canadian Armed Forces” indicates that this aircraft was newly painted after the unification of the three military services of Canada into one non-cohesive fighting force. Brought into being by then Minister of Defence, Paul Hellyer, unification signalled the death knell of the RCAF and RCN, their service specific uniforms and traditions. After unification, all services were required to use Canadian Army ranks and stripes, new army-style green uniforms and to get along. The move was reviled by everyone... even the Army. Pilots crewed aircraft wearing forest green uniforms like those worn by bakery-delivery men, and the Navy was no longer allowed to wear navy blue. Morale plummeted. Long career airmen and sailors simply quit, rather than wear green. Eventually, the Navy and Air Force got back a reasonable facsimile of their old uniforms, the Navy got their ranks back and just last year, the Air Force got its old name back – the Royal Canadian Air Force. Photo: RCAF

Despite the fact that the CL-13 Canadair Sabre retired from front line service in 1962, it continued on in specialized roles for years, including the celebrated Golden Hawks (1963) and this Sabre 5, clearly flying over rugged Canadian landscape near No. 1 (F) OTU, Chatham, New Brunswick in 1967. She sports brand new, modern era roundels, but this one is clearly not the standard we know today, as the leaf is too small. Perhaps they were trying to iron out the details when this one was applied early in its development. I believe this Sabre operated with the Sabre Transition Unit at Chatham. Photo: RCAF website