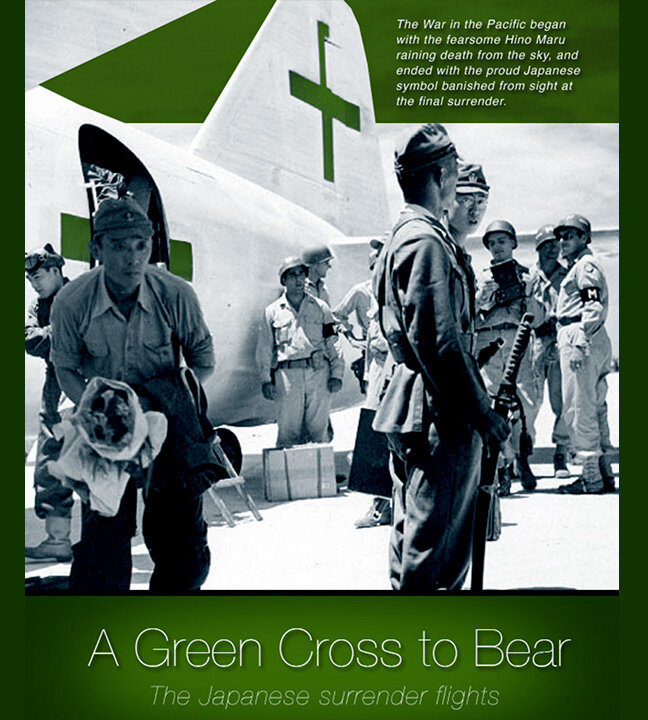

SURVIVOR — The Werner Schwantje Story

Illustration: Dave O’Malley

Back in the early 90s, I was working with Canadian photographer and publisher John McQuarrie on a book entitled ‘Til We Meet Again about vintage warbirds and the Canadian experience in the Second World War. We salted the pages with short vignettes written by veterans who flew the aircraft we were depicting. In these short pieces, we chose not to use photos but rather drawings to illustrate the stories. In the mid 90s, these veterans were all in their seventies and in fairly good health. Pilots who shared their stories included well known characters like beer-scion Hartland Molson, former Premier of the Northwest Territories Erik Neilson, Flying Officer Charlie Fox, and Squadron Leader Hart Finley. There were fitters and gunners and pilots, but one stood out from the rest.

His name was Werner Schwantje, an elegant, well-turned out 70-something government lawyer with Revenue Canada. I had been expecting him to drop in and hand over a photo of himself to scan as a reference for an ink and pencil illustration for the book (lead image to this story). I had grown up with stories of heroic RAF and RCAF pilots fighting the Nazis back to Berlin and Werner Schwantje would be the first German combat veteran I had ever met. I have to admit my expectations of what he would be like were coloured by a childhood filled with images of duel-scarred, grey-eyed, Ritterkreuz-wearing, cold killers flying mottled and ugly-beautiful Messerschmitts and Focke Wulfs. I would not have been surprised by a heel click, a monocle or a sneer. But Werner was none of that.

Werner Schwantje was a quiet and thoughtful man, bemused by and grateful for the interest in his story. He seemed the kind of man who thought sartorial style was a form of good manners for he was dressed impeccably. Back in those days, when I was more sartorially inclined, I immediately respected a man who was well turned out. He wore a light weight trench coat over a grey suit, crisp white shirt, dark narrow tie and his thinning grey hair cut high on the side and swept back in the teutonic fashion once favoured by young Luftwaffe fighter pilots. He spoke with a German accent worn smooth by four decades in Canada with which he told a story, somewhat abashedly, that was nothing short of miraculous — surviving two bail-outs of burning aircraft, a pair of flaming crash landings and a forced landing after being hit by flak. For a man who had obviously participated in some of the key battles of the war’s end and who had survived when nearly all of the Luftwaffe was being swept from the sky, he was remarkably modest and decidedly wary of looking the braggart or displaying arrogant tendencies. Like most of the young men who fought in the war and lost comrades, he was a committed pacifist in his later years.

We sat together for a while chatting about the book and his experiences in the Luftwaffe, and then he handed me an envelope containing a small yellowed photo of himself from his time flying Messerschmitt Bf 109s. It showed a square-jawed and more solidly built version of himself leaning out from the open cockpit of a 109, leather-gloved right fist pumping some unremembered triumph, his left hand displaying a large chromed watch — the kind that fighter pilots everywhere love. On the left sleeve of his battle dress were the bar and wings of a Luftwaffe Leutnant. That photograph was a rare memento from the finest and most dramatic days of his life when he risked everything to fly low across the English Channel and pop up over some of the most heavily defended British naval ports or to scout the battle lines from France to Germany. The photo was a fading and impermanent record of when he was young and a proud Staffelkapitän in a specialized reconnaissance group of the Luftwaffe known as a Nahaufklärungsgruppe — a unit attached to the army and dedicated to short range battlefield reconnaissance.

I took the photo, scanned it, handed it back to him and then chatted with him for a short while longer. We shook hands at the end and I never saw him again, but the experience has remained vivid in my mind’s eye for 30 years.

Werner’s story was extraordinary to me, but in fact, as he would surely confirm, it was no more so than any front line combatant of the war — Allied or Axis. An ordinary tale from an extraordinary time, but his story deserves the light of day as do those of all the millions of men and women who participated in, were destroyed by or were swept along by the global holocaust that was the Second World War. All we know about his story comes from Werner himself and it’s remarkably short on detail. We’ll try to fill in some gaps and make it more fulsome with images and background, but the story is his to tell in the manner and detail he wished. Gott hat dich beschützt, mein Freund. Nun ruhe in Frieden

Dave O’Malley

Surviving War’s End — by Werner Schwantje

After getting my wings I was assigned to a new and secret squadron that was the first to do short-range reconnaissance using the Messerschmitt 109. By February of 1944 the Allies had air superiority and we considered ourselves lucky to even get off the ground from our base at Dinard* in France without getting shot. Shortly after the invasion in Normandy some of our anti-aircraft gunners were shooting at anything in the air as they believed that there were no German aircraft flying anymore. At least one battery did an excellent job by shooting me down early one evening. The battery commander was, of course, very apologetic and loaned me his car to facilitate my return to the squadron. On the way back we were forced to abandon the vehicle when we were attacked by bombers. His lovely little automobile was completely demolished so there was a little bit of justice that day.

High command was obsessed with discovering where and when the Allies would invade Europe so we were often tasked with obtaining aerial photos of British port cities for our intelligence people. These missions were always nerve-wracking because we could hear buzzing in our earphones as soon as we passed through about 50 metres altitude. This told us that we were picked up by their radar and we knew at least eight Spitfires would be scrambling somewhere to meet us over the coast of England. We always went in two-plane sections and our orders forbade us to engage in aerial fighting except to defend ourselves. Our technique was to cross the Channel right on the wave tops to avoid being detected on radar and then, at the last moment, make a dash up to 8,000 metres to take our photos. Sometimes, as we were diving back to the water to make our way back to France, we would see fighters climbing to find us but we always managed to evade them because we had altitude and speed over them. But they knew where we lived and often waited for us close to our base in France. It was always quite interesting.

Luftwaffe ground crew load cameras and film into the camera bay on a Messerschmitt Bf 109 reconnaissance aircraft at Dinard-Pleurtuit airfield, France, while the pilot discusses his flight plan with his crew chief. Schwantje’s NaGr 13 [Nahaufklärungsgruppe] recce fighter group was housed here from August 1943 to June 1944. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Another angle on the same Dinard-based aircraft as in the previous photograph showing details of the German Handkammer aerial reconnaissance camera. Photo: Bundesarchiv

Related Stories

Click on image

A reconnaissance variant of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-8/R5**. Similar to those flown by Schwantje’s Nahaufklärungsgruppe 13 (NaGr 13), this aircraft (200413) flew with sister recce unit NaGr 12. Photo: Asisbiz

The unit badge of 1 Staffel Nahaufklärungsgruppe 13 — a red eagle watching enemy shores — was worn on some of the unit’s Messerschmitt 109 Gs and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s (Left). Photos: Left, Asisbiz; Right, Ebay

My mission to photograph the port city of Plymouth in May of 1944 was particularly memorable. Clouds covered that day but, as luck would have it, when I reached 8,000 metres over the target I found a lovely big opening and got perfect pictures. As soon as I landed my undeveloped film was rushed off to our Intelligence people in Paris. Later I was told that the BBC broadcast the following day said something to the effect that, “If the Germans believe that Lieutenant Schwantje’s photographs of Plymouth will hinder our invasion plans they are sadly mistaken.” So we learned that British intelligence had penetrated our own somewhere. I would love to have heard that broadcast myself, but it was a capital offence to listen to ”enemy propaganda.” I don’t know if they really would have shot us but I do know we never did listen in.

During his time at Dinard-Pleurtuit airfield, Schwantje no doubt enjoyed the pleasures of the seaside resort of Dinard just a pleasant afternoon walk to the north of the field where he could sun himself on warm sands Plage de l’Ècluse or sip a cold bière at the Gallic Hôtel (centre). Today, Dinard remains a popular ocean resort in Brittany. Photo: thegallic-hotel.blogspot.com

One morning late in May, 1944, when we were climbing over the Channel on another mission to England, the cockpit of my plane suddenly filled with smoke so that I had to throw the canopy off. I thought I could save the plane and tried to reach the French coast, but at 200 metres, the stuttering engine burst into flames and I had to bail out. As luck would have it, I was at that moment exactly over the tiny German-occupied island of Alderney, so I was spared a swim and possible drowning in the Channel.

German Kriegsmarine sailors stroll down a typical British street in the town of Saint Anne on the Channel Island of Alderney during the Second World War. Werner Schwantje would have found a safe emergency landing field here as nearly all of Alderney’s residents were evacuated before the arrival of the German occupation. During the war, the Nazi’s worked thousands of European slave labourers to death on the island to build fortifications and according to some, a chemical warfare factory.

After the invasion we were often ordered to locate the constantly changing front line. To survive in a German airplane over Europe at that time in the war forced us to fly at tree level or hide in the clouds. This meant we could not use cameras so we switched to what we called “eye reconnaissance” and made a verbal report on what we saw to intelligence.. Often they gave us a fighter squadron as escort because our information was so vital. On July 1st, however, it wasn’t enough. An American Thunderbolt caught me in the open and followed me into the clouds firing his machine guns the whole time. I remember the bullets looked like little raindrops in the clouds. I lost him after that one pass, but he had shot out my rudder and I was forced to crash land. Somewhere there is an American Thunderbolt pilot with one more kill than his record shows. In case he is reading this, it was just south east of Caen.

Black-11, a Messerschmitt Bf-109 G of NaGr 13 that has force-landed. Photo: Asisbiz

Werner’s brother Helmut (above) was also a Luftwaffe fighter pilot, seen here receiving some sort of honour next to his Focke-Wulf Fw 190. Perhaps is was a milestone flight of some sort, but possibly some high honour like a Knights Cross. Oblt. Helmut Schwantje was a Staffelkapitaen in I. Gruppe of Schlachtflieger-Geschwader 102 from August 1944 to February 1945. SG 102 (originally Stuka-Geschwader 102) was a training, not a fighting unit. It was formed in October 1943 with two groups (6 wings of 12 Fw 190s each) to train Jabo (Jagdbomber = fighter-bomber) pilots at the Schlachtflieger-Schule 2 at Memmingen in Bavaria. Photo: falkeeins.blogspot.com

Flugplatz Dinard-Pleurtuit airfield a few kilometers southwest of St. Malo

** The suffix 'R' stood for Rüstsatz , or equipment package. R5 consisted of photo reconnaissance equipment, a fuel transferring system from the auxiliary tank to the main 400 litres fuselage tank with the aid of compressed air coming from the engine supercharger. The number of auxiliary tanks could be one under the central fuselage belly or two; one under each wing.

The following piece [Not including photographs and captions] was first published in February of 1985 in Observair (Volume 22, Number 2), the Canadian Aviation Historical Society Ottawa Chapter newsletter following a presentation Werner was invited to make to the CAHS members in Ottawa about his war flying experiences. We publish it again to fill in some of the blanks in Werner Schwantje’s story

The Other Side

As one who had survived the Second World War, Werner Schwantje considers that period as a fascinating and interesting time of his life, but examining it from today’s perspective there is nothing that would persuade him now to have participated in that war or any other. Like most of the young people at the time who believed that Germany had been unfairly treated by the Treaty of Versailles, Schwantje was proud of his country’s renewed strength. The feeling of young boys was that to be a “real” man meant to have been in a war. So it was not surprising that the youth were eager to be involved in Germany’s fight. Schwantje was no exception and when he reached the (minimum) age of 17, he joined the Luftwaffe.

Schwantje’s air force career began in October 1940 and as a new recruit underwent basic military and pilot training. The standard [ab initio] trainer was the Heinkel He 72 B biplane with the Junkers W 33 and W 34 for instrument and radio instruction. Aerobatics were flown with the Bücker Bü 131 Jungmann two-seater and Bü 133 Jungmeister single-seater aircraft. Also used in the training was the French-designed, two-engine Caudron C.445.

Werner completed his elementary flying training on the Heinkel He 72B “Kadett” biplane powered by a BMW-Bramo Siemens-Halske Sh 14A 7-cylinder air-cooled radial engine of approximately 160 horsepower. It was about the same weight empty as a Tiger Moth or Fleet Finch, but more powerful. Photo via Wikipedia

For aerobatic training and just plain fun in the air, Werner flew the nimble, sturdy and much-loved Bücker Bü 131 Jungmann two-seater and Bü 133 Jungmeister, an aircraft so suited to aerobatic flying that the assembly line was re-opened briefly in 1994.

The steady Junkers W 33 and W 34 (above) were flown by Werner for instrument and radio instruction. Likely the Junkers carried more than one student, each taking time at the controls for instrument training and at the radio (This is not Werner in the photo). Photo: luftwaffereviews.blogspot.com

Werner also gained time on an unlikely twin-engine trainer — the French-built Caudron C.455 Goéland (Seagull). 55 Goélands were captured by the Germans after the fall of France and pressed into service as a general duty transport crew/navigation trainer and production of the type was allowed to continue to equip Vichy Air Force, the Luftwaffe and Lufthansa. (This is not Werner in the photo) Photo: falkeeins.blogspot.com

Once he had obtained his pilot’s licence in October 1941, Schwantje volunteered for Stukas but, instead, he was one of those selected as eventual pilots of a short-range reconnaissance version of the Messerschmitt Bf 109. He was instructed in the basics of tank and artillery tactics, navigation and ground feature recognition, and trained as an observer and camera operator. In April 1942, and now a qualified observer, he was promoted to lieutenant.

Next came a stint at a fighter school to learn skills of combat and formation flying and target shooting. And, as a last step before being assigned to a frontline unit, there was training with the Bf 109 to hone the techniques of ground target recognition as well as advanced photography and gunnery.

By spring of 1943, the training was now complete but before proceeding to a frontline squadron Schwantje and another pilot were assigned to pick up two 109Gs in Vienna and ferry them to a unit on the Russian front. While carrying out a routine circuit test flight before setting out on the trip, Schwantje’s aircraft caught fire for an unknown reason and quickly the intense heat caused him to lose consciousness. As related to him later, the 109 must have kept its general course to crash in flames. It just happened that the fire brigade was on its daily exercise near the crash site and within seconds the flames were extinguished and Schwantje was pulled from the wreckage. After recuperating from a broken spine and severe burns, he was judged medically unfit to fly and was assigned to the staff of his last training school. But this did not prevent him from arranging opportunities to fly.

Then in early 1944, through the cooperation of understanding doctors, Schwantje managed to get posted to NAG 13 [Nahaufklärungsgruppe], a short range reconnaissance wing at Dinard on the French coast of Brittany. The wing consisted of two squadrons: the Channel-based unit flying Bf 109s and its companion Staffel with Fw 190s near Nice in southern France. The Channel operations extended from Southampton to the west coast of Cornwall. The daily routine was to carry out convoy surveillance in two-plane flights at very low altitudes. Indeed, after one mission Schwantje’s wingman returned to base with his propeller tips bent back and part of the fuselage with rivets torn off.

In early May, a series of incidents occurred which first began with the order to fly a mission over Plymouth to determine the concentration of the suspected invasion fleet. On the first attempt, Schwantje and the squadron commander encountered a large number of British fighters at 10,000 metres and had to turn back. The following day a similar attempt failed and the tactic was changed to fly low over the Channel and then climb up to altitude just before reaching the target area. Even though British aircraft were prominent in the vicinity, Schwantje was able to avoid them and successfully carried out his run over Plymouth. Only he was able to obtain a very clear photograph of the target, for which he received a commendation from headquarters in Paris. The BBC reported this attempt in its news broadcast with direct reference to Schwantje but went on to state that this one photograph would reveal very little about the assembly of the allied invasion fleet.

A high altitude Luftwaffe reconnaissance photo of Plymouth, England’s Royal Navy dry docks, basins, fuel storage (top left) and repair facilities on the Tamar River (top centre). Luftwaffe photo

A few days later a similar photo mission was planned for Exmouth. As leader of the two-plane section, Schwantje took a low altitude route across the Channel and in the climb up to 3,000 metres over the English coast oil started splattering the windscreen and smoke began to fill the cockpit. The first thought was to bail out but because he was over unfriendly territory and there was no visible fire Schwantje decided to attempt to reach the French coast. He was able to land his 109 safely near Cherbourg where inspection of the aircraft revealed that vibration has caused the oil line to touch the hot engine and thereby create a hole for the oil to leak out.

As no photos were obtained on this attempt, the same mission was repeated two days later. Exactly the same incident occurred at about the same time into the flight and Schwantje decided to follow the same routine procedure. At 500 metres and approaching the French coast he noticed to his left an island with an airfield (Alderney, on of the Channel Islands). Not being sure where he was, and also being at low altitude, Schwantje elected to try the island. But in coming closer he saw that the field was covered in obstacles. Now at 200 meters with flames beginning to engulf the engine, there was no alternative but to parachute. He was rescued by residents of the nearby barracks who informed him that he would have to spend a week on the island—altogether is was not an unpleasant experience—as the weekly ship had just left on its run to the mainland.

After this experience Schwantje was given a well-deserved rest during which he was asked to fly an Fw 190 that had been delivered by mistake to his unit, to the companion squadron in Southern France. On 3 June he was recalled and made the return journey by train via Paris arriving at Dinard late of June 5. Early the next morning an air raid alarm sounded but Schwantje was too tired to respond. When finally awakened, he rushed to the operations room to find that everyone had gone to the airport. The air raid alarm had signalled the Allied bombing which had been launched against strategic points along the coast in order to disguise the site of the invasion.

Throughout the next days, the 109s flew many low-level reconnaissance missions along the coast. On June 10 Schwantje was assigned to carry out a flight over the invasion area to determine the position of the Normandy front lines. This was a near suicidal mission as the Allied forces had swept German planes from the skies. The flight was carried out at very low altitude, taking the invading army by surprise. Schwantje was just thanking himself that no shots had been fired when, suddenly, there was a loud bang and his machine became engulfed in smoke and flames. There was no choice but to bail out. With a struggle he was able to extricate himself and parachute to the ground while avoiding rifle fire that was directed at him. Quickly he hid in the hedgerows.

After some time he noticed that the people looking for him were in German uniforms so he decided to give himself up. But the Germans took no chances with their prisoner and began escorting him through the fields and hedges. However, before reaching the nearest command post the soldiers became convinced of his identity. They explained that they belonged to an anti-aircraft battery and were under instructions to shoot anything that flew as there was not expected to be German planes over the front lines. Indeed, Schwantje had fallen victim to their skill.

It took a number of days, travelling through areas under constant bombardment, to return to his unit which had now moved to Chartres. From here, reconnaissance flights were carried out under fighter escort and the need for this was demonstrated clearly when on one mission Schwantje was pounced upon by a Thunderbolt. He managed to get away into the clouds but the engagement damaged his rudder and he had to make a forced landing. In another incident some days later, Schwantje had just taken off to wait in the air while his companion overcame some technical problems when he noticed other planes and, assuming they were the escort, proceeded to join them in their circuit above the town. All at once he noticed the markings of the British Spitfires. Quickly he eased off and dove away undetected into the sun.

The squadron’s losses began to mount and in August the retreat began through Paris, across Belgium and eventually pausing on the Rhine, southwest of Frankfurt. During the Battle of the Bulge in late December the unit transferred to the east side of the Rhine. This engagement was followed by moves to several other airfields in the next months.

At the end of March 1945, Schwantje, who by this time was the unit’s senior pilot at the age of 21, was selected to begin training on the twin-jet Messerschmitt Me 262 with which his unit was to be re-equipped. Because of continuing air raids and delays to repair damage, he was never able to get an Me 262 off the ground before being recalled back to his squadron.

In the final weeks of the war, Schwantje was selected for training on the Messerschmitt Me 262 “Schwalbe” (Swallow). Fortunately for him, his training ended before he could get one airborne. The factory-fresh, unpainted Me 262 depicted in this photo landed at Frankfürt/Rhein-Main airfield, Germany on March 30, 1945, piloted by defecting Luftwaffe pilot Hans Fay. It would soon be transported to Wright Field, Ohio where it would be thoroughly tested and compared with the American P-80 then in development. It was lost in a crash when an engine caught fire. The test pilot baled out successfully. Photo: USAF

A Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R2 (W.Nr. 230785) “Yellow 11", of Werner Schwantje’s NAGr. 13, abandoned to the Allies at Fritzlar, Germany in April 1945. Perhaps this is one of the 109s Werner had flown. Photo: Asisbiz

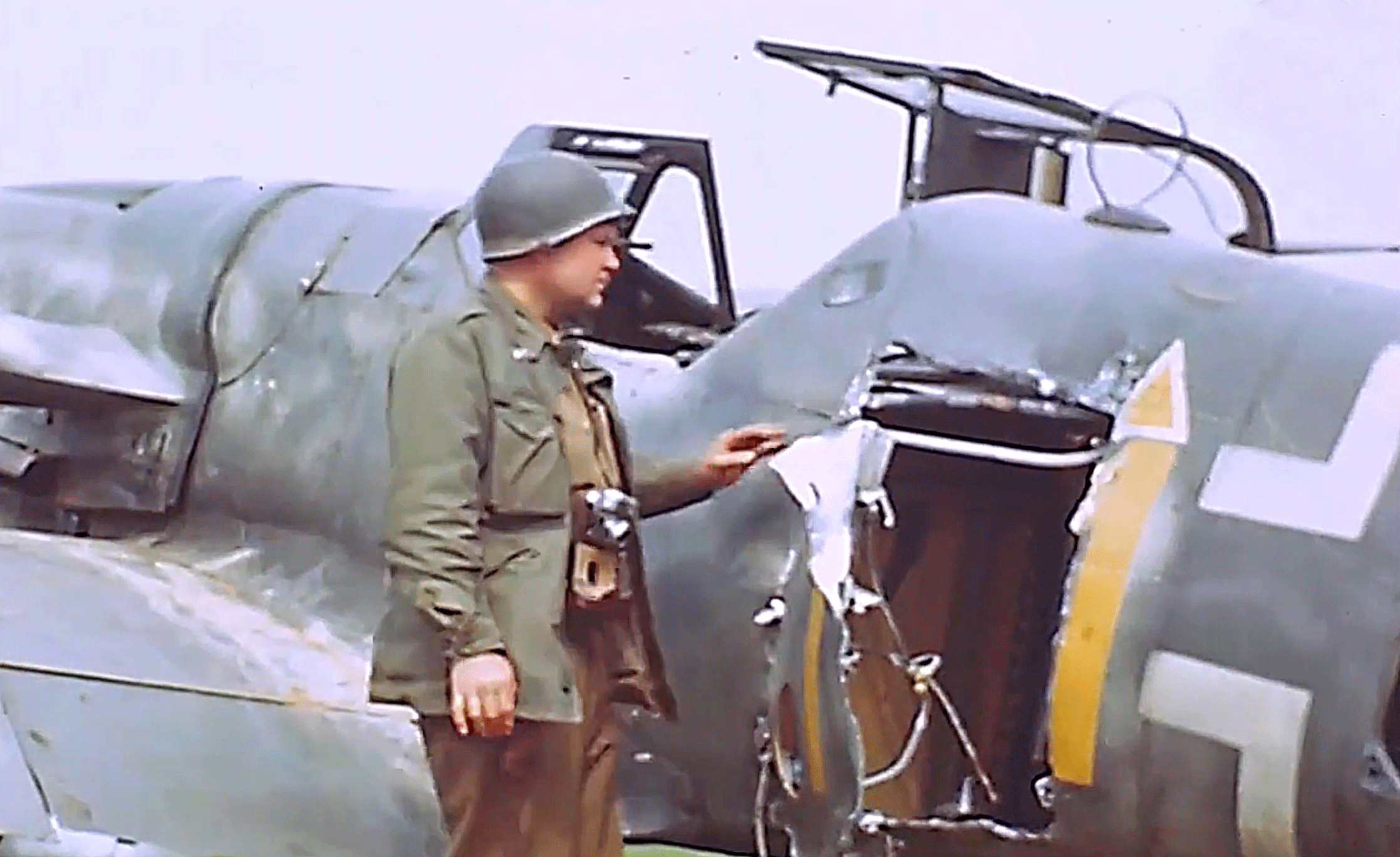

American pilots inspect an abandoned Messerschmitt Bf 109 Yellow 11 of Schwantze’s NaGr 13 at Fritzlar Flughaven (airfield) in April, 1945. Screen capture image via Youtube.

An American GI reporter inspects a gaping hole cut into the port side of Yellow 11, a Messerschmitt 109G of Schwantze’s NaGr. 13. The hole appears to have been cut deliberately and one wonders if this was souvenir hunters or intelligence people wanting quick access to cameras inside. Screen capture image of US Army film via Youtube (lazar Bakic).

By the end of April the German command structure had started to deteriorate quickly and confusion of orders began to take hold. Many rumours circulated including one that the Germans would be joining the Americans against the Russian advance. When it came, Germany’s surrender broadcast was devastating to the dedicated soldiers and so with discouragement Schwantje decided to attempt to obtain an airplane to fly to his home near Hanover. As he was making his way to the airport a flight of Thunderbolts appeared and his first instinct was to prepare for an impending attack. But the aircraft just flew over and to Schwantje this was a sure sign that the shooting war was really over.

Postscript

Shortly after the Normandy invasion, NaGr 13 moved from Dinard on the coast to a safer “fliegerhorst” (air base) at Chartres where they remained until August. Werner and his unit then moved through a series of bases, reflecting the progress of the war — Charleville (the Ardennes), Charleroi (Flugplatz Gosselies, Belgium), Köln (Fliegerhorst Wahn in Cologne), and Neustadt an der Weinstrasse (Fliegerhorst Lachen-Speyerdorf, southwest of Mannheim). As the war came to a close, they moved to Odheim, southeast of Mannheim and finally Oberschleissheim where they took final residence at Fliegerhorst Schleissheim.

After the war, Werner, with the aid of Baptist missionaries, emigrated to Canada in the mid-1950s, where he joined his brother Helmut who had already emigrated to Vancouver. Here he found employment as a photogrammetry technician, something related to his reconnaissance work in the war. On one particular on-line forum, a post at the time of Werner’s death from someone who claimed to be a friend indicated that he had spent five years in a Soviet prisoner of war camp at war’s end. This might explain the delay in emigrating to Canada to join his brother, but there is no further evidence to support that claim. He never mentioned this to me, but this may be due to his reluctance to speak at length about himself.

In 1969, Werner earned a law degree for York University’s prestigious Osgoode Hall Law School. He then practiced law with the Canadian federal government in Ottawa for the next 30 years. He married a woman named Gisela in 1973. Werner Schwantje died in Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital, on Sunday, July 13, 2008, at the age of 85. His brother Helmut had proceeded him 2003.