SWEET DREAMS AND NIGHTMARES

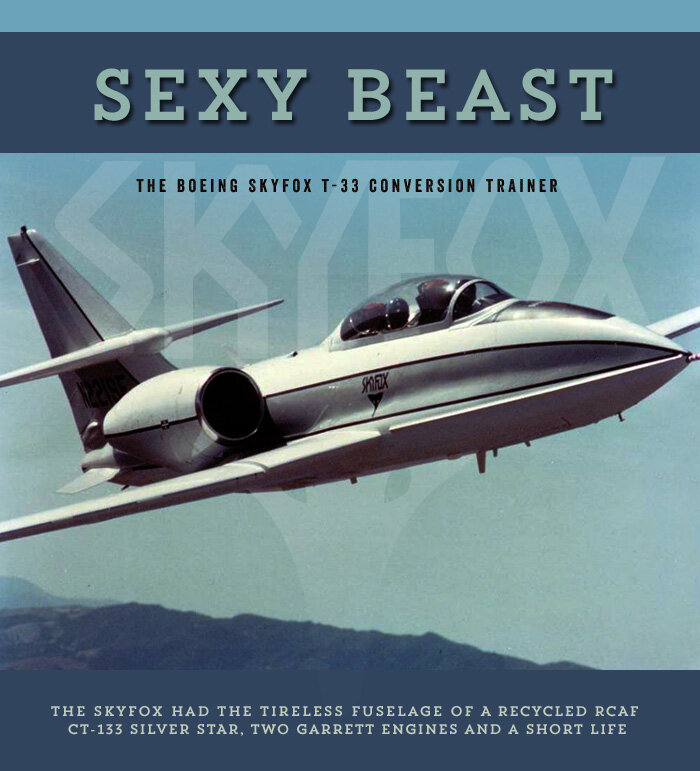

Over the years, I periodically and repeatedly came across two entirely different series of photographs, taken 45 years apart. The first group was taken in 1950 by famed LIFE magazine photographer Loomis Dean. These images, purporting to be of a wealthy man cavorting with family and a couple of beautiful women off the California coast on a luxury PBY Catalina, were in fact a staged event put on by the company that refitted the old US Navy amphibian. Today we would call this an advertorial. The black and white photographs are particularly compelling because of two young blonde Hollywood starlets juxtaposed with the big aircraft and the older executive types who hosted them. The second group was taken in 1995 by expatriate Ken Stanford, an amateur photographer who, while working in Saudi Arabia, photographed a crumbling, bullet ridden wreck of a PBY Catalina rotting on a beach in Arabia where the Gulf of Aqaba opens into the Red Sea. These images came with a strange story of a family outing, Bedouin militiamen, international intrigue and a dream riddled by bullets.

The Catalinas in both instances were postwar conversions to a luxury flying yacht known as the Landseaire. One demonstrated the dreamlike glamour and recreational possibility of the flying yacht, while the other was a forlorn remnant, telling a story of one of those dreams wrecking on the shores of a hostile country. I kept those images in separate folders for a couple of years, and recently it occurred to me that they were related, and worthy of a story together.

The Consolidated PBY, in both its Catalina and Canso iterations, was one of the most versatile aircraft of the Second World War. The American-designed flying boat was first developed as a patrol bomber for the defence of American coastlines and the far-flung island archipelagos of the Pacific Ocean. It was utilized as a reconnaissance platform, bomber, submarine killer, liaison transport and as an Air Sea Rescue aircraft, plucking downed aviators from the despair of a ditching. The big twin-engined aircraft was first designed as a pure flying boat, capable of operating solely from water. A later development, the PBY-5A added an amphibious capability with retractable undercarriage and one of the most versatile aircraft in history was born.

The PBY was called the “Catalina” by the British first and the “Canso” by Canadians who built them in two plants in Canada. Total production at the close of the PBY assembly lines included 2,160 aircraft from San Diego, 235 from New Orleans, 731 from Canada (Cansos, and other variants for the USAAC and other Commonewealth air forces) and 155 from another plant in Philadelphia for a total of 3,281. The USSR built a small number under licence as well. With such a capable aircraft available in such numbers, it was only a matter of time before the low-time surplus examples found their way into civilian hands, including some with Southern California Aircraft Corp., a partner with Consolidated’s new corporate identity as Convair.

While fighter aircraft and bombers would have no future use after the global conflict of the Second World War, surely the plethora of the versatile, but now-silent Consolidated PBY Catalinas and Cansos could be put to some alternate use. Here, an aerial view of the seaplane base and ramps at Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida in October 1945, shows nearly 75 of the dependable but surplus flying boats tied up and awaiting their fates. Photo via The Flying Boat Forum

This photograph appears to be taken on the ground of the same group of Catalinas from the previous photograph. Both were taken at Jacksonville in 1945. A quick check back and forth shows me that the second Cat on the right row is dark and the third Cat in the left row is also dark in both images, leading me to believe the two images are of the same line-up of surplus Catalinas. Photo via The Flying Boat Forum

Many of the fully amphibious Catalinas and Cansos were acquired by civilian companies after the war and flown in the commercial cargo business, forest fire fighting and as private passenger planes. Some entrepreneurs, including Southern California Aircraft Corp.’s Glenn Odekirk, saw in the elegant and long-legged amphibian a new role as an extreme luxury flying yacht. He envisaged rich postwar industrialists and wealthy adventure-loving businessmen flying anywhere in the world aboard a luxury yacht capable of operating on land, sea and air and he called it... the Landseaire. No kidding. Truthfully, the name Landseaire applies to the Consolidated PBY conversions carried out by Southern California Aircraft Corp., but the name has come to mean any PBY reconfigured for the same purpose or even for passenger service.

Perhaps the following article, by Maurice F. Allward, about the emergence of the Landseaire, which appeared in Great Britain’s Flight magazine on 24 July 1953, will shed some light on the thinking behind the Landseaire’s development. Allward’s article, entitled Airborne Yachts—Luxury Conversions of Wartime Catalinas, was pretty overtop in the praise, but it tells us a lot about the interiors. The article was written in 1953, and the images in the Flight story show a more refined Landseaire with an aft boarding stair, fared tender boat under wing and other improvements over the one in the LIFE magazine shoot.

In fact, coincidentally, the Landseaire used in the Loomis Dean LIFE shoot crashed and was destroyed in a river landing accident near Ubatuba, State of São Paulo, Brazil on 5 July of the same year–only two weeks before Allward’s article was published. It was then Brazilian registered as PT-APK.

Airborne Yachts—Luxury Conversions of Wartime Catalinas –

“Since the war there has been much talk—if nothing else—of bringing flying within the financial reach of the proverbial man in the street—of attempts to produce aircraft costing less than cars and with comparable running costs.

But little has been heard of special aircraft being produced for the people at the other end of the scale—those who have come up on the treble chance or who are still one jump ahead of the tax collector. It is thus with pleasure that I pass on details of some good work being done to rectify this sad state of affairs by Glenn E. Odekirk, head of the Southern California Aircraft Corporation, who is busy converting ex-government PBY-5A amphibious Catalinas into air yachts.

With over 4,000 hours in his logbook, Odekirk has his own ideas of what an executive type airplane should be like—and be able to do. In his own worlds, ‘It seemed like no one was getting real utility out of a private airplane. Normally, it’s just a means of transportation in which you ride from here to there with varying degrees of comfort. So, I decided to build an aerial luxury yacht in which you can land and live almost anywhere in the world with all the comforts of home.’

After numerous flights, in almost all types of weather, Odekirk thinks his ‘Landseaires’, as he has named the rejuvenated Cats, are the near perfect answer. The facelift which he prescribes transforms the austere interior into a concentration of extravaganza seldom equalled and rarely surpassed. Little remains that would be recognized by any wartime crew who flew in these eminently trustworthy amphibians.

Related Stories

Click on image

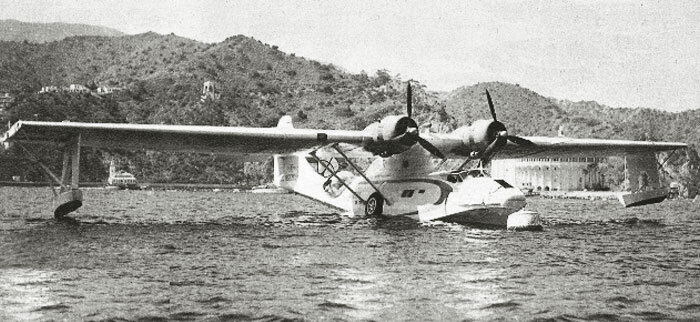

A newly fitted-out PBY-5A Catalina “Landseaire” (N69043) flying yacht awaits the arrival of her guests at the Convair (former Consolidated) factory in San Diego, California in February 1950. This particular Catalina was made at Consolidated’s San Diego Plant as Bu34045 (US Navy). The photographs of this part of the story all come from Time Life’s archive and are meant to demonstrate how the rich and famous lived at that time—private airplane, pretty girls and booze. Some Landseaire conversions had retractable stairs fitted just aft of the planing bottom, but this version has a simple ladder. According to brochures, when the amphibian is afloat, the steps or ladder make useful diving platforms. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

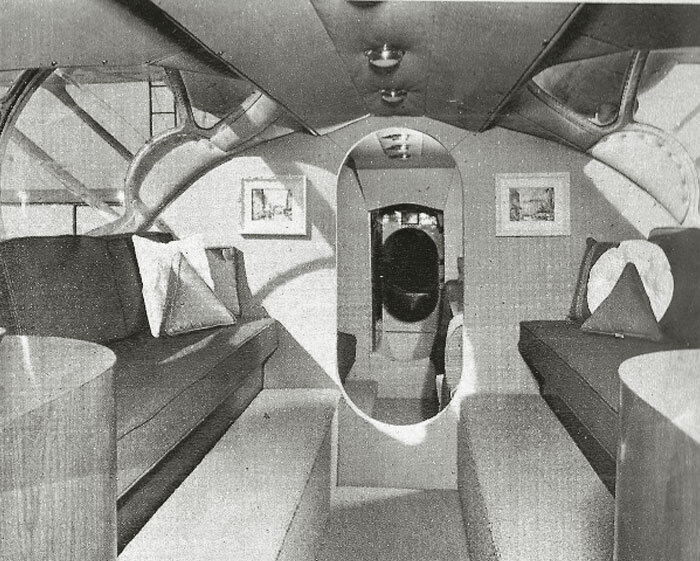

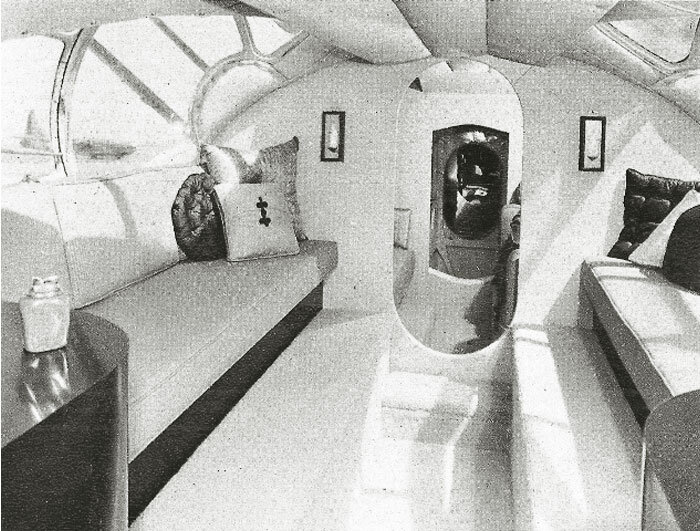

The first step in the conversions is the moving forward of the flight engineer’s controls into the cockpit. This enables the aircraft to be handled by the pilot and co-pilot alone and provides more ‘living space’. Sleeping accommodation is provided for eight persons in three double beds and two singles. Near each bed are an individual light, radio switch and speaker, curtains, vents for air conditioning system, and a telephone. Occupants may contact the shore by means of a marine ship-to-shore telephone. In addition to this item of ‘electrickery’, the converted aircraft are fitted with no fewer than seven communications receivers, two transmitters, a broadcast receiver, FM-AM radio and a built-in television set!

Passengers can thus communicate anywhere in the world—to ships at sea, to another aircraft in flight, or to a private telephone on land.

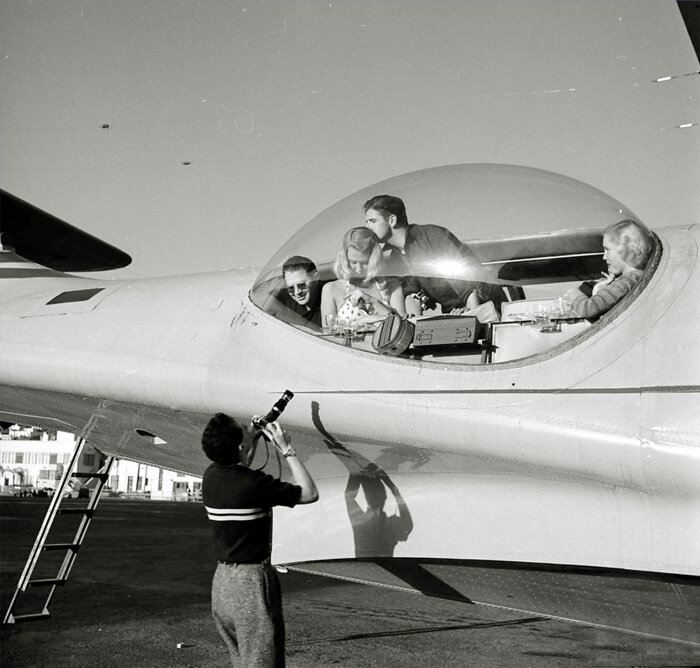

During the day the two single beds in the aft or ‘observation’ cabin serve as seats. This cabin occupies the former mid-gun positions. On the starboard side, in place of the wartime blister, is a special one-piece blister typical of the luxuriousness of the other innovations: it is of specially free-blown Lucite to achieve good optical qualities without distortion and costs over £1,000. Measuring 7ft in length by 4&1/2 ft deep at its widest point, it also has a permanent camera tripod in the centre, permitting panning of 180 degrees up and down, fore and aft.

A door to the rear of the observation cabin leads to a built-in stairway. This gives comfortable access when on land and can also be lowered afloat, where it makes an ideal diving board. Much of the 104ft wingspan can be used for sunbathing.

Noise is kept to a remarkably low level by a 4in-thick lining of Fiberglass. Overall carpeting adds further to the comfort. A shower bath, in waterproof plastic, runs hot and cold water. The w.c. is electrically flushed when on water; in the air a chemical toilet is used. The galley, in white porcelain and stainless steel, rivals the equipment of the most modern kitchen. A three-plate cooking range, oven, large refrigerator and frozen-food unit are installed.

Externally, few alterations are made. The nose gun-turret and bomb-aimer’s window are replaced by a sleek clipper-style bow. Slung under each wing, where bombs and torpedoes used to hang, are two 14-ft dinghies. Each boat fits snugly against the wing and is raised or lowered by a built-in electric hoist. Cruising speed with the boats in position is 175 m.p.h. The maximum range is, as might be expected, exceptional for a ‘private’ aircraft, and is given as 3,000 miles.

A Landseaire costs a lot of money—$265,000 is the basic price— something not far short of £100,000. This, coupled with heavy operating costs, virtually lifts the craft beyond the reach even of most millionaires. King Farouk had one on order before his abdication, but mostly it is the executive class of wealthy corporations that are attracted by these fabulous toys. The fact that the Landseaires are amphibious does mean, however, that they have a considerably wider scope of usefulness than more conventional ‘executive’ aircraft. Those sold are said to fly quite usefully on cross-country trips for plan and location inspection, using airfields, landing strips, waterways and rivers.”—Maurice Allward, Flight

Once the first new Landseaire prototype was complete, it was necessary to get the story out to the public. Odekirk invited some fellow executives from Southern California Aircraft Corp., a few family members and rounded up a couple of very attractive, very young aspiring Hollywood actresses and assembled them at the Convair factory ramp in San Diego’s Lindbergh Field. He managed to get LIFE magazine to send one of their accomplished photographers, Loomis Dean, and two of his assistants to capture a day with the Landseaire. The agenda included air-to-air photography, landing on the Pacific Ocean for some fishing and sunbathing, lunch, cocktails, cards, lounging, a party on board and some sightseeing of San Diego’s navy base and the coast.

We would like to thank Time LIFE and Flight magazine for making these images and story available online for non-commercial use. Their collective record is an astonishing look back across the last century, not from the view of an historian, but rather the immediate view of a weekly or monthly magazine. If you wish to view many more of the photos taken by Loomis Dean that day in 1950, click here. To view the Allward story in Flight magazine three years later visit FlightGlobal.com.

On the land

Here, Glenn Odekirk (centre) chats with pilots and mechanics prior to the day’s outing and photo shoot. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Convair mechanics and Southern California Aircraft Corp.’s passengers discuss the coming flight, which was likely pitched and arranged by Convair PR guys to publicize the new Landseaire luxury flying yacht conversion. The title on the white lab coat says “Aeronautics”. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

One of the young blonde models in a sundress watches a mechanic working on the wing as preparations are made to get underway. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Here, we see possibly four models posing for another LIFE photographer while the Landseaire is still on the ramp. The starboard observation blister of this aircraft was a single moulded piece of Perspex, while the port blister was the standard variety with opening panel. Photographer Loomis Dean had at least two assistants this day—one with him in the Landseaire and one in the accompanying photo ship, so this may be Dean in the photo. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

This Convair PBY Landseaire had a small rowboat tender slung beneath the starboard wing, allowing passengers and crew to reach the shore after landing. One wonders if Diane was one of the ladies in attendance this day. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Another shot, either at dawn or at the end of the day, shows the Landseaire’s dinghy attached to the bottom of the starboard wing. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

On the sea

The “executives” seem like they have no idea what they are doing, paddling the Landseaire’s boat with oars instead of rowing. In the background, the models lounge on the PBY’s wing while crew members seem to be very interested in their condition. The man on the left in the row boat is Glenn E. Odekirk, then president of Southern California Aircraft Corp. The Oregon State University (OSU) alumni website says this of Odekirk: “Odekirk during the 1930s and through the Second World War was the assistant to the president of Hughes Aircraft and had a very close, professional relationship with the man who was president—millionaire eccentric Howard Hughes. For several years, the two flew around the country together, testing the young OSU engineer’s ideas and arguing constantly over the most trivial matters of airplane construction. It was Odekirk who carefully examined airplane after airplane during the 1930s to find the one Hughes eventually used to set his record-breaking round-the-globe flight of 91 hours.”

“A plane Odekirk helped design during 1935, known to historians as the H-1, set a world speed record of 352.39 miles per hour in September of that year, beating Raymond Delmotte’s (of France) record of 314.32 miles per hour. The plane was revolutionary for its time and was one of the first planes in history to sport retractable landing gear and special counterstruck screws and flat rivets to reduce wind resistance.”

“Odekirk’s most famous project was the work he contributed to the legendary Spruce Goose and was aboard when Hughes piloted the plane on its one and only flight on 2 September 1947.” Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

To back up my claim that the executive in the rowboat and in many of these LIFE magazine images is indeed Glenn Oderkirk, I searched the web for images of him. There were very few, and only one that clearly backs up the claim. This image of Odekirk was found on Flickr on Tairemartyn’s photostream. There is no doubt that the man in all these images, who seems to be in charge and having a great time, is indeed the President of the company that built the Landseaire. With Odekirk’s connection with Howard Hughes and nearby Hollywood, it’s no surprise that he was able to round up a couple of beautiful, young and aspiring actresses to play the role of executive’s privilege. Photo: Tairemartyn on Flickr

Odekirk’s Hughes pedigree was definitely strong, working on many of Hughes’ most advanced projects including the Spruce Goose and Hughes D-2. The Hughes D-2 was an American fighter and bomber project begun by Howard Hughes as a private venture. It never proceeded past the flight testing phase but was the predecessor of the Hughes XF-11. The only D-2 was completed in 1942–3. Here, Glenn Odekirk (left) and Howard Hughes inspect the left engine mounts of the big prototype. Photo: Wikipedia

Glenn Odekirk, left, plays the part of a tycoon on a fishing trip with a flying boat full of Hollywood starlets waiting for him to catch dinner. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

In the motion picture, The Aviator, about Howard Hughes and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Glenn Odekirk plays an important role as Hughes’ friend and engineer. The part of Glenn “Odie” Odekirk is played by actor Matt Ross. This image shows Odie smiling at the engineer’s position on the Spruce Goose as Hughes (in background) lifts the giant H-4 Hercules off of Los Angeles Harbor, Long Beach.

The Landseaire looks gorgeous with the coast of Southern California in the background. This was the scene that was imagined by the creators of the Landseaire concept—sky, sea and land all together in one experience… and bikinis. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Photographer Loomis Dean (in the rowboat) approaches the quietly rocking Landseaire, as guests await on the wing top and posing (rather coyly, I might add) on the wing strut. Family members, including children, peer from the port side blister. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The family peers out from the port side blister. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

A crew member prepares to drop from the wing onto the fuselage as Loomis Dean in the rowboat takes this image from the bow. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Reflected in the port side blister glass, we see the photographer Loomis Dean (or his assistant) steadying the rowboat “Diane” as Glenn Odekirk and his pal chat with daughter and mother in the Landseaire. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

From the open hatch of the port side blister, a young child watches as the two models do a little wing walking. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

From the co-pilot’s hatch, a bathing-suited model looking very Marilyn Monroe-like gets the attention of some local Southern California fishermen. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Up on the upper wing, one has to think that on a hot day the surface would be unbearable. This, however, appears to be a fine mid-winter day in Southern California and the ladies pose seductively for the photographer. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

One of the models is assisted down from the wing after the entire group posed for photographs. The women appear to be in two separate groups, the Blonde Bathing Suit Models and the Older Business Suited Ladies, who actually may be the wives of Southern California Aircraft Corp.’s executives. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

There seems to be quite a few people used in this photo shoot. The mustachioed bald guy appears only in these images of the ladies being lowered to the fuselage and later having drinks in the Landseaire. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

And in the air

Perhaps I have the sequence all wrong, but let’s just say that the Landseaire and its model passengers did an air-to-air AFTER the water photography. Here, the camera ship, a Vultee SNV Valiant sneaks in close as Glenn Odekirk (left) chats up a blonde model while viewing the world around them. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

One of the finest selling features of the Convair PBY Landseaire was no doubt the observation blisters. Not since the airship Hindenburg did passengers enjoy such a remarkable view of the world around them. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The passengers gaze out over the California Coast and the Vultee SNV Valiant camera ship. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Another great angle on the same scene shows us the wonderful viewing platform with a high wing offering unobstructed view down from the blisters and the large square windows along her sides. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Sliding astern, we see the clean lines of the Landseaire. The small dinghy named Diane is no longer slung beneath the starboard wing. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The Landseaire churns into a setting sun on the California coastline. Note the difference between the port observation blister and the starboard one which has a hatch. Sadly, this particular Catalina Landseaire would survive only three more years when it was lost in a crash at São Paulo, Brazil under a Brazilian registration. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

At the end of a long day of photographing the Southern California Aircraft Corp. Landseaire, the pilot banks the flying boat away from the Vultee Valiant camera ship and heads toward the California coastline in the distance. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Here, an “executive” and his daughter sit at the starboard side observation blister and enjoy the scenery. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

With afternoon sun streaming in the smoke filled cabin, one of the models poses languidly with a cigarette on one of the interior couches. Like airliners today, each place was equipped with an air vent and an overhead reading lamp. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

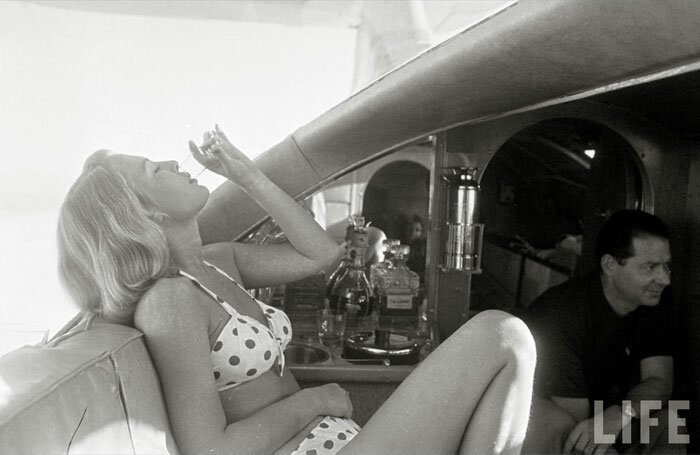

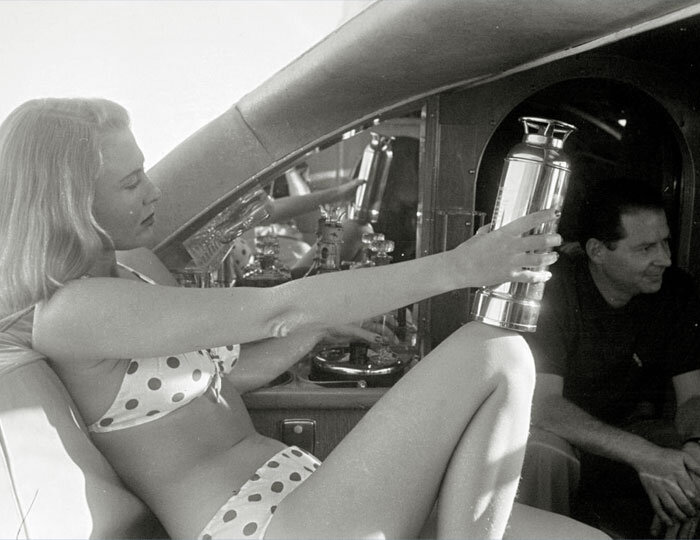

One has to realize that this is 1950, when a woman’s place was in the kitchen. Part of the dream presented to the potential wealthy industrialists, who were the demographic for the sale of the Landseaire, was that a successful man could fly anywhere and still have a pretty girl prepare his meals for him or serve him drinks. While today this would be considered downright sexist, in 1950 it was considered the dream of every man. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

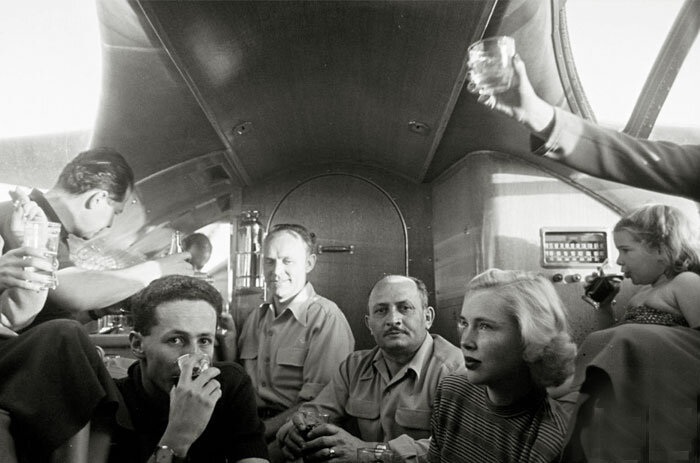

Executives smoke and drink while pretty models read magazines. The idea here was to show that the Landseaire was a home away from home. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Dad and daughter gaze from the port side blister upon the scores of mothballed Second World War destroyers moored at San Diego Navy Base. This appears to be a different “dad” (Odekirk) and the little girl seems to have changed from her bathing suit... probably all part of the photographer trying to get as much out of the shoot as possible. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

A rather pleased and smug looking Glenn Odekirk prepares a drink at the fully stocked bar. This was the age of the High Ball, Tom Collins, Side Car and the Gin Rickey retro cocktails. Odekirk was indeed living his dream. The model who appears to be in the background is actually in the foreground and reflected in a mirror. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The Marilyn Monroe-like model peers from the blister. One has to believe that the air inside the Landseaire was stifling, what with the noise, the smell of avgas, cooking and cigarettes, combined with the heat of the sun. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

One of the models, sporting an “itsy-bitsy polka-dot bikini”, pours a dainty glass of wine down her throat while lounging provocatively on the starboard side blister sofa. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The young model plays with the fire extinguisher seen on the bulkhead in the previous photo. This image is the promise of the Landseaire Flying Yacht—sipping High Balls in your own winged world, high above the plebs below and surrounded by extremely beautiful and scantily clad women who laugh at your every word. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Early on in the flight no doubt, before she slipped into her bathing suit, the beautiful model basks in the sunlight of the port side observation blister while the Landseaire flies north along the California coastline. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

In the world of a Landseaire owner, pretty girls in bikinis laugh at your jokes. That was the idea behind this scene. Since this was long before the advent of the cell phone, the young woman can is enjoying a conversation using the ship-to-shore telephone. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

“Did someone here order a blonde?” Even in 1950, the Madmen of advertising knew that sex sells. All the vices are represented in this shot—smoking, drinking and philandering. Like the video screens found in today’s business jets, the instrumentation over the bulkhead doorway in this shot showed passengers the altitude, speed, time and direction. Not much has changed in corporate air travel in the next 60 years! Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

A young model smiles coyly as photographer Dean lines up the Vultee Valiant camera ship in the background. Though LIFE magazine archives credit Loomis Dean for both the interior and the air-to-air shots, it is not possible for him to be in both places. Clearly he had an assistant or two, as there are shots that show another photographer in the Landseaire with him. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The Vultee Valiant made a logical choice for the photo ship as Convair, the makers of the Catalina, was an amalgamation of both Consolidated and Vultee. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

The money shot. I debated long about whether to include this particular shot in this story as it may be considered too risqué and possibly too politically incorrect for a serious website. It certainly was one of the photos in the series that got my attention. I did include it because it shows us just how the Landseaire was marketed to the boorish, sexist, powerful, aging executives of the day. This must have created quite a sensation in 1950. The ad men and promoters knew full well that sex sells cars, so it was logical that sex would sell flying yachts. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

At some point in the photo shoot, the Landseaire hit a little inclement southern California weather. Flying through clouds and rain the pretty actress/models had to snuggle up under some blankets to keep warm. The inside temperature must have been difficult to regulate near the blisters. This may have been the reason the Landseaire had been equipped with blankets in the first place. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE Magazine

Landseaire owners could fly the open skies with their friends, partying and enjoying life. It was an intoxicating promise, one which president Glenn Odekirk (centre) thought could make him rich. Not 100% sure, the younger man in the left foreground with the drink may in fact be photographer Loomis Dean. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE magazine

The ultimate promise of the Landseaire—to fly wherever an adventurous and wealthy man’s imagination could take him... in a world of peace. Photo: Loomis Dean, LIFE magazine

To this day, a very small number of Catalinas remain in airworthy condition and G-PBYA operated by Plane Sailing Air Displays Ltd in the UK can still attract the ladies! Here she is at the Scalaria Air Challenge on the Wolfgangsee near Salzburg in Austria in 2011. Photo: Copyright David Legg

I have searched the copies of LIFE magazine from the February date of the photo shoot all the way to November and have not found any of these LIFE images in the actual published magazine. Still, the images of the Landseaire contrast sharply with the end result of one such promised adventure on a Landseaire—the misadventures of Thomas W. Kendall and his family. Kendall, another Californian, built a number of PBY Landseaire-like luxury conversions later the same decade. He wanted to live up to the promise of venturing out into the world and seeing it from the air, so he set out on a round-the-world voyage in one of his aircraft. The sad end of his dream, on a sun-hammered Saudi Arabian beach, contrasts dramatically with image created by Odekirk, Dean and the two particularly lovely models.

From Dream to Nightmare

The sad end to Thomas Kendall’s dream of freedom

In the 1950s, Los Angeles industrialist Thomas W. Kendall and his wife decided to create a similar flying yacht to Odekirk’s Landseaire. Purchasing three surplus Second World War PBY Catalina’s, the Kendalls’ hired noted Los Angeles interior designer George Erb to convert the warplanes into a trio of flying and floating luxury suites. Kendall, a retired businessman who made his fortune in air conditioning, planned to create a business converting and leasing them, with plans to build 14 similar conversions—Kendall purchased 13 surplus PBYs in 1956, one of which still exists today at the San Diego Aerospace Museum.

Erb gave each of the three Catalinas their own unique colour scheme and personality creating a Gold, Turquoise and Red and Black aircraft. Each of the giant amphibians had a capacity to sleep fourteen with covered foam rubber sofas that converted into beds, a full galley, lavatory and even a dining room with a table for eight.

Each of Kendall’s Landseaire’s was uniquely designed and fitted out by renowned interior designer George Erb. Each aircraft was known by its interior palette—this was the Turquoise Ship, which was presumably the dominant colour. The brochure material at the time stated “The Turquoise Ship with beautifully textured upholstery fabric specially designed wall pictures, gay colors, deep luxury carpet and colorful cushions, is truly a home aloft.” Photo via Paradise Leased Blog with Steve Vaught

Tucked and rolled and ready for adventure. Looking just a tad tacky by today’s standards, Kendall’s Gold Ship Landseaire with its padded walls had all the charm of a New Orleans cat house. Photo via Paradise Leased Blog with Steve Vaught

The Red and Black Ship by George Erb, one of Kendall’s three Landseaire conversions, shows the most promise as an elegant and comfortable place for wealthy owners to relax while exploring the world. Photo via Paradise Leased Blog with Steve Vaught

Two of the three Kendall PBY Landseaire conversions on the ground in California. He originally planned to purchase 14 used Catalinas for conversion to the Landseaire idea. Photo via Paradise Leased Blog with Steve Vaught

Something you don’t see very often—a PBY Catalina, one of Kendall’s Landseaire conversions moored off of Catalina Island off the California coast. Photo via Paradise Leased Blog with Steve Vaught

According to one blog, called Paradise Leased, the Kendalls embarked on an around-the-world voyage with the three converted PBYs. “In 1959, the Kendalls, both licensed and experienced pilots, embarked on a year-long round-the-world trip with the three planes, bringing along their four children, aged 8–24, as well several other lucky friends including prominent L.A. physician, Dr. Ellwood L. Schultz and his wife. Kendall and his 24-year-old son Bob piloted one plane, Mrs. Kendall another, and Dr. Schultz, also a licensed pilot, the third. The amphibious planes were so complete in their mobility and the luxurious accommodations aboard, the L.A. Times declared, ‘About the only way you could improve on this arrangement would be to take an automobile or two along on the journey. Then all you need to do is drive away from the plane and do some sightseeing.’ Today, they, no doubt, could do just that by simply sticking a few ‘Smart Cars’ in the cargo holds. And who says money can’t buy happiness? It can certainly buy fun!”

At this point, I cannot tell what happened to Kendall’s plan to fly around the world in three converted Catalinas. It seems from the Los Angeles Times that this was his plan. However, there is little record of what happened next. We do know that one of those Catalina conversions was used and damaged while filming a feature film called SOS Pacific. This happened in Madeira in 1959, and the aircraft was photographed by several aviation enthusiasts on the ground at Croydon Airport in South London in the fall of that year, where it was being repaired.

Thomas Kendall’s Landseaire N5593V parked at Croydon Airport in 1959. Kendall had acquired this as a stock Consolidated PBY-5A from US Navy surplus at Litchfield Park, Arizona and fitted out as a Landseaire with luxury appointments. The aircraft had flown to Croydon from a film making assignment in Madeira, for the 1959 movie “SOS Pacific”. Kendall was in the process of flying his Catalina (N5593V) on an around-the-world voyage with his family. Photo: Jeremy Hughes Collection

Four cinema “Lobby Cards” for the feature film drama SOS Pacific with one of them showing us Catalina Landseaire N5593V being abandoned in the Pacific as part of the film’s plot. It is interesting to note that this film was in black and white and the cards are in colour. They may have been hand coloured afterward, as the registration here is red, but on the marooned wreck in Saudi Arabia, it is definitely blue. The irony is that the film SOS Pacific, the filming for which the Kendall Landseaire was used, was about a group of passengers forced to ditch their Catalina in the Pacific. This was a foreshadowing of the difficulties in which Kendall would eventually find himself in Saudi Arabia. The film starred only one notable actor—Richard Attenborough.

Another great shot by Jeremy Hughes in 1959 shows the Kendall Landseaire at Croydon still. While on a film location at Madeira, the Portuguese archipelago 500 miles off the coast of Morocco, the aircraft suffered bow damage and was being repaired at Croydon. Photo: Jeremy Hughes Collection

The Kendall Landseaire at Croydon. Photo: Jeremy Hughes Collection

The entire Kendall family joined this Catalina Landseaire (N5593V) in Croydon—Kendall, his wife, four children (one of which, Bob, was old enough to be co-pilot), his secretary and her son. They appear to have set off on their dreamed-of round-the-world flight from London, bound for Egypt and the Pyramids. In Egypt, they were joined by another LIFE photographer, David Lees, who was to record their adventure for the famous magazine.

After visiting Cairo, the Suez Canal and Luxor, they landed at the Strait of Tirana (between Egypt’s Sinai and Saudi Arabia) and anchored the aircraft a short distance from the shore to spend the night there. This would be the last landing that PBY ever made, and the Kendall family had a harrowing near-death end to their plans—in the end they got an unforgettable family memory.

There is probably no better way to learn about what happened to the hapless family than to read the actual story as written by Kendall himself for LIFE magazine and view some of Lees’ photographs. I have transcribed from a scanned copy of the 30 June 1960 issue of LIFE magazine the entire article as it was written nearly 55 years ago. With LIFE magazine’s forbearance, we offer it to you in its entirety as is.

The LIFE magazine account of Kendall’s misadventures

“Last spring Thomas Kendall, a retired California industrialist of 44, started a leisurely trip around the world in a PBY amphibian that he had converted into a lavish flying yacht. Kendall’s party consisted of his wife Miriam, his children Bob, 24, Susan, 15, Paul, 11, Kathy, 9;his secretary, Mrs. Ramona Shearer, and her son Stephen, 11. Photographer David Lees joined the group during the trip to record part of it for LIFE. One evening a few weeks ago Kendall landed in the Gulf of Aqaba in the Middle East and the pleasure trip turned into a harrowing, almost fatal adventure, which he describes in the following article.

The beginning of the Kendall family trip had all the flavour and extravagance of a Turkish Pasha travelling throughout his empire. Here, locals in the Middle East gawk as the entourage sets up patio furniture on the broad wing of the Catalina. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

The number one selling point of the Landseaire was most certainly the waist blisters, which offered passengers an unparalleled view of the world below them. Here, Kendall’s family gather at the starboard blister as dad circles the Great Pyramids at Giza. Peering from the PBY’s plexiglass blister at the pyramids are Mrs. Kendall (left), Mrs. Shearer (right) and the four youngest children. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

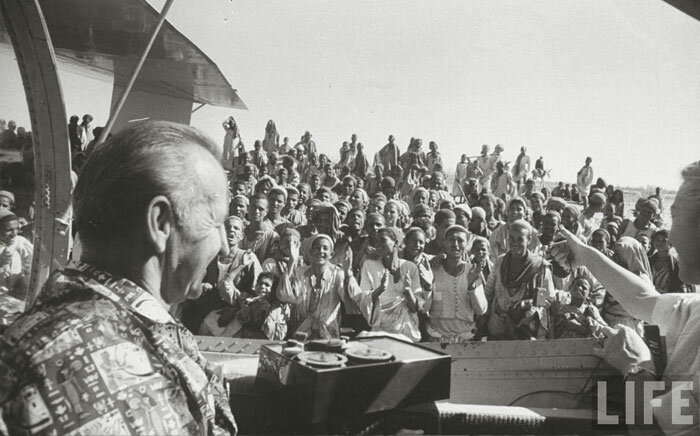

Kendall, in his signature Hawaiian shirt, smiles benevolently for the hoard of Egyptian gawkers who must be singing, as Mrs. Kendall is holding out a microphone to record on a tape deck. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

The LIFE magazine website page for this image states that it is in Saudi Arabia. Local citizens crowd around the Kendall’s Landseaire for a closer look. It seems that Kendall has dropped his landing gear to enable him to beach the aircraft higher. This is something he did on the day he was attacked. This looks like a similar crowd and orientation to the beach as the one in the previous photograph. However, the LIFE site claims the previous image was taken in Egypt. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

Nightmare windup of family’s dream trip–as told by Thomas Kendall

“Fifty feet from the beach I let down the landing gear so that the plane wouldn’t be washed ashore during the night. By the time we were secure it was pitch black and the wind had become quite strong. We cooked supper and the children climbed into their bunks.

I was outside making a final check on our anchorage when I heard someone yelling. I thought it was Arabic, but the rattling of the wind and waves made it impossible to tell from which direction the shouts were coming from. I went back into the plane and told the others not to go outside. But we yelled, ‘Okay… we’re okay.’ And shouted, ‘Salam’ to show we were friendly. Susan told me she had seen the outline of a man gesticulating, but by that time the voices had stopped.

The following morning, Wednesday 23 March, we arose at 6 and immediately hoisted our American flag above the pilot’s compartment. We figured if anybody was around, the flag would identify us as being friendly. We had been told that the Saudi Arabs were friends of the United States. What we did not realize was that many of their soldiers don’t even know their own flag, let alone the Stars and Stripes.

During breakfast, David Lees and my son Bob mentioned that before sunrise they had seen five men watching us from knoll 150 feet from the plane. The men were dressed as soldiers and one carried a machine gun. After a while they had walked away. Since they hadn’t approached, we figured they had just come to look us over and had left when they saw we were peaceful. We had become used to seeing soldiers everywhere we went in the Middle East so we thought nothing of it.

By 7 o’clock the children had waded ashore and were wandering on the beach, collecting sea shells. Bob and I worked on the plane all morning and David Lees took some pictures. By noon, the temperature had reached 100º and we all went for a swim before lunch. During the day we saw a few people walking off in the distance, but they were so far away we couldn’t tell if they were adults or children.

Sightseeing, dining alfresco, and beach walking were very enjoyable pursuits for the Kendall family. Kendall in his signature white hat and colourful shirts in the farthest from the camera in this photograph taken by David Lees on the very morning of the attack by Saudi militiamen—just a few hours later. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

After a late lunch I went up on the wing to check the left engine. Bob was in the water checking some equipment in the nose. Stephen and Paul were wading in the shallows about 60 feet away, playing with our bright blue rubber life raft. Everyone else was in the plane. When I finally buttoned up the engine, I stood up and glanced around. Except for the boys, I saw nothing but rocks, low hills and empty sand. I looked at my watch. It was 4:32 exactly. Then I heard what sounded like distant firecrackers. My first thought was that some local Bedouins were celebrating the Muslim holiday of Ramadan, which was then in progress. In Luxor, Egypt, our last stop, they had celebrated by firing off a cannon. Suddenly, I noticed little splashes in the water beside the rubber raft. Somebody was shooting at the children.

I yelled to Stephen and Paul to swim to the plane immediately, and I jumped down off the wing into the cockpit and ran back toward the tail to help them aboard. As I ran I shouted for everyone to lie down on the floor because we were under fire. Mrs. Shearer ran with me to the tail and we watched our small sons dog-paddling very slowly toward the hatch, just their heads above water, towing the raft for cover between themselves and the bullets.

By now machine-gun and automatic-weapons fire was hitting the plane, I don’t know how long we stood there screaming at the children to hurry—it felt like eons. Mrs. Shearer exposed herself to direct fire to help me pull them aboard, and Stephen said, ‘Mother, they’re shooting at us.’ After that I don’t remember anyone saying anything, just the noise of the bullets tearing into the skin of the plane. It was like being in a barrel which someone was banging with a steel pipe. Later, David Lees said that in all his eight years of war he had never experienced such concentrated fire. We estimated 3,000 to 4,000 rounds were fired. At least 300 hit the plane.

The ambush lasted 30 to 40 minutes, and only the cowardice of our attackers saved our lives. If they had come closer instead of hiding behind a knoll three quarters of a mile away, I am certain we would all have been killed.

During the barrage I told the three smallest children—Kathy, Paul and Stephen—to lie on the bathroom floor in the wheel well. It was the smallest compartment but probably the safest. It was below the water line, and our heavy canned goods were stacked around the walls. My wife lay on top of the children like a big bird trying to protect them with her body.

They were still in considerable danger, however. Although it would be almost impossible for them to receive any direct hits, the wheel well was directly under the gas tanks. I worried about gas draining out of the perforated tanks and then maybe ignited by an incendiary bullet.

David Lees lay aft in the blister compartment. Mrs. Shearer was on the floor of the forward compartment and Susan was under the galley table. I moved about a good deal at first, checking hatches and seeing that everybody was okay. When the firing got too bad I lay down near Susan.

After a while we saw the upholstery was smoldering from a tracer bullet. I knew gas must be leaking everywhere. I could either stand up to start the engines and maybe get shot, or I could stay on the floor and maybe get us all burned alive. When I got up to go to the pilot’s compartment to throw some switches so we could get out of there, there was another burst of fire and I felt a blow in the right side. The bullet entered just below my ribs and it spun me around and threw me about six feet. I fell down backward. When Mrs. Shearer heard me grunt that I’d been hit, she raised her head to look at me. Just then a bullet hit her right arm, exactly where her head had been. She clawed a big chunk of metal out with her fingernails but there were two more pieces she couldn’t reach. I was dazed for a moment but she gave me a towel and then, somehow, lying on her back, she lifted the seat up so I could reach under and connect the batteries. Then I went forward to the cockpit to throw the switches.

My son Bob, who was still outside the airplane, was pounding on the hull, yelling for a knife so that he could cut the mooring line. Mrs. Shearer got a kitchen knife from the galley and crawled up to the cockpit and handed it to him through the window. Then Bob climbed in through the pilot’s hatch and Mrs. Shearer piled some tables around him for protection while he started the engines. I crawled aft to close the hatches.

A scream from the children

My wife was still lying over the children, guarding them with her body. But just then there was a crash in the wheel well and I heard the kids scream. I yelled,‘Is anybody hit?’ A bullet had skimmed over their heads and struck the big bathroom mirror so that glass shattered all over them. I shouted, ‘No more squawks unless somebody is really hit.’ And from then on there wasn’t a peep out of them. No one cried or panicked. The children knew we were in a serious position and that seemed to make them grow up on the spot.

I continued crawling aft on my stomach and, just as I raised up to wriggle over one of the watertight bulkheads, I got nicked in the fanny, or so I thought at the time. I could see where the bullet had frayed the bottom of my swim trunks. I thought, ‘Ha,ha! You missed me!’ and it seemed such a good joke that I actually laughed. Later, the doctor told me the bullet had gone clear through me and the hole where it came out was six inches from where it went in.

The engines would run, though roughly, and Bob started them up. I shouted to him to get the wheels up. I didn’t think we’d get airborne, but at least we could taxi out of range. He couldn’t hear me over the engine noise, so I crawled forward and put the landing gear selector valve in ‘up’ position. The airplane began to move very slowly. I looked back and saw water pouring in the open tail hatch. I was in a good deal of pain by then so I shouted to David Lees to close it. He struggled with it for three or four minutes but he didn’t understand the mechanism so I had to go back again. My daughter Susan came along to help me. While we were struggling, the watertight bulkhead leading to the front of the plane closed behind us and the tail compartment began to fill with sea water. We kept trying to get the hatch down but when the water got up to our chins, we had to give up. It took all our strength to pry open the watertight door against the water pressure in the tail section. When we got it open partway I pushed Susan through, but I didn’t have much strength left. When I tried to follow her, the door slammed shut on my ankles. I blanked out. Somehow Susan forced that heavy door open enough to get my feet through. She still has a big ugly knot in her arm where the door banged shut on her at some point and broke blood vessels.

By the time we got up forward the plane had taxied about half a mile—out of range, although the gunfire continued—and had run aground on a coral reef. Water was pouring in through foot-long gashes in the fuselage that looked as if they had been ripped by a giant can opener. Everything was floating around. All we could see of the children was their faces above the debris. A four-inch stream of oil was gushing out of the right engine and the fumes were nauseating.

I ordered everybody out through the pilot’s hatch and they made for the shore 100 yards away. The water was only five feet deep. There was oil and gasoline all around us. We had 900 gallons of fuel and it was pouring out of the perforated tanks and splashing off the wings like a heavy rain off a roof. I still don’t know why we didn’t go up in flames. David Lees helped me wade ashore. Stephen kept saying, ‘I love you, Mother’, and Mrs. Shearer kept saying, ‘I love you, Steve.’

When I reached the beach I lay down, lightheaded and really feeling the pain. Everyone was standing around barefooted, dripping wet, and smeared with oil and blood from the mirror cuts and our wounds. We were all in bathing suits except my wife and Susan and Mrs. Shearer, who had on shorts and blouses. Stephen and I had shirts. Paul was clutching the big American flag which he grabbed when we abandoned ship. He didn’t once let it out of his sight until we got back to civilization.

Bob went back to the plane to get some first-aid supplies. After a while the others heard him in the cockpit babbling and laughing and acting strangely. When Susan and David Lees went after him, they found him giddy and half-asphyxiated from the gasoline fumes. They couldn’t make him come out. At last my wife waded and swam back to the plane. ‘Bob,’ she called, ‘I need you. It’s your mother.’ That got him to stick his head out so David could grab him and haul him ashore.

We saw our attackers for the first time when three trucks carrying 60 to 80 men came bouncing over a hill a mile away. The men were screaming barbarically and firing wildly in our direction. We all stood up and put our hands in the air. Paul waved a white T-shirt and his flag. As they approached I decided to walk forward and meet them. David Lees tried to come with me, but I told him to stay back with the group and if I got shot to see that they take cover as best they could.

Those soldiers were the fiercest looking men I have ever seen. They were Bedouin tribesmen serving in the Saudi Arabian army. Many had long matted hair and their teeth were filed. Most wore a scarecrow combination of tribal dress and khaki uniform. They were all wild-eyed and highly excited, showing their guns. A man running toward me alongside the first truck was screaming and pulling the pin on a phosphorous grenade. Two other men jumped off the first truck and all three shoved their rifles into me while the rest continued on to where my family was waiting. I was in considerable pain and could barely hold my hands up, and I had nothing but bloody bathing trunks and a sports shirt, but they frisked me. Then they stepped back apace and all three pointed their rifles at my chest. I watched their fingers, which were literally twitching on the triggers. I said, ‘American, American.’ Finally, one of them repeated the word so I knew he understood. He was about 50, bald, with crossed bandoliers on his chest and a red, checkered Bedouin skirt tied over his pants. The youngest man, about 20, had a red and white sweat rag around his forehead and a bandolier around his waist. The one with the grenade wore a G.I. uniform and a steel helmet. He had the pin out of the grenade, so he had to hold down the grenade trigger with one hand and handle his rifle with the other. I just stood there wondering which one was going to go off first.

A wild desert ride

When the trucks got to the others, Paul showed our flag and someone gave them our American passports, but this had no effect. Later we learned that most Bedouin troops are illiterate and that even the general who had ordered the attack could neither read nor write.

In 5 minutes the soldiers had used their keffiyeh headdresses to blindfold all of us except the 3 youngest children. Then they shoved us into two of the trucks and started off across the desert. We were lying on the floor under some filthy camel blankets, bouncing over the rough, rocky desert.

I was in extreme pain and felt myself going into shock. One minute I was in a rosy, relaxed glow and the next moment, I started shaking with uncontrollable chills. Miriam and Kathy were lying next to me, trying to warm me. Under Bob’s direction, 11-year old Stephen tore his shirt and used half of it to make a pad for my wound. He tied the other half around his mother’s arm, which stopped the bleeding somewhat.

I didn’t want to frighten the children, so whenever I felt a bad time coming on I said to them in a normal voice, ‘Now I am going to put on a big act to see if I can scare these fellows into taking us to a hospital right away. So when I start making a lot of noise and moaning and shaking, don’t you worry about it.’ Then I’d relax and let myself go a bit, and that helped.

After two hours’ ride we stopped at their camp, and the soldiers took everybody but me out of the trucks. They apparently figured I wasn’t worth unloading because I was going to die anyway. Finally I slipped off my blindfold and got out of the truck myself. I fainted at least five times in the process, the last time as I jumped to the ground. It then took me five minutes just to get up on my feet. The Arabs just watched to see if I was going to make it.

I walked toward the only building in the cluster of tents. No one tried to stop me. Inside, I found my family and they helped me lie down. The children put some blankets over me. We were under guard in a bare 12-by-12-foot adobe room with a dirt floor. There was a single kerosene lamp, and a chest which our guard sat on.

Men kept milling in and out to look at us, and one of them brought us a handful of small tomatoes to eat. Much later, we were fed some sickly sweet tea and rice. One Arab gave Paul a huge white floppy robe, and he stood in the corner looking like a shmoo, still holding on to his American flag. Mrs. Shearer was the only one of us who smoked, and an old Arab kept offering her cigarettes, holding them so she had to stretch her hand way out to get them. He was watching the rings on her finger.

For a time we played word games to keep the children from thinking about what the rest of us were thinking about. It was cold and windy and after a while we all huddled together on the floor and tried to stay warm.

About 1 o’clock they got us up to load us back in the trucks. They tried to take the women first, one at a time. I got in the way and protested that we would all stay together. I didn’t have to put it into words—I just looked them straight in the eye and they got the idea.

I think by this time it had occurred to them that they might have pulled a colossal blooper. When they took us back to the trucks, we feared they would drive us out into the desert, shoot us and pretend we never existed. As we were climbing aboard the trucks a man pulled Mrs. Shearer’s wedding ring off her hand.

A mile from camp we stopped at a tent where we met a man who could speak a little English. He told us we were being taken to a hospital. Half an hour later the trucks suddenly turned back to camp and we were dumped back in our adobe room. The man who spoke English told us a wireless message had come through saying that in the morning the ‘Big King’ was coming to see us.

The Arrival of the “Big King”

I was in great pain during the bitter cold night. My abdomen became so swollen that twice I almost stopped breathing. At daybreak they gave us some English canned pineapple and more tea and again spoke about the ‘Big King’ who was coming. The soldiers got all dolled up in clean uniforms. Peeking through the cracks in our boarded-up window we could see a welcoming party assembled, wearing long blue robes with gold braid.

About mid-morning I was lying on the floor with my head propped against the wall, still without bandages or first aid of any kind, when the guard brought us in a soft mattress and put it on the wooden trunk. It was not for me. The ‘Big King’ came in and sat down on it. He was Prince Khalid ibn Saud, one of King Saud’s sons. He wore flowing white robes. He was tall, courteous and very quiet. With him was a Saudi Arabian Air Force officer who interrogated us in English and translated for the prince.

It became clear at once that the ambush, the attack and the treatment we had suffered were all due to the Arab’s fanatic fear of Israel. They had somehow convinced themselves that all of us, including my wife and children were Israeli commandos in disguise. Their first question was: what had happened to the jet fighters that had escorted us onto the area? Next they asked us about the battleship that had sailed in behind us, and about the Israeli troops that were massing to support our invasion.

We said we had seen no other men, planes or ships and were simply a family of American tourists. They asked why we had returned their fire if we were not Israelis, and why we had thrown our guns overboard and why we had refused to surrender.

Despite our protestations they continued asking variations of the same outlandish questions. We found out later that the interpreter was not translating correctly. He was not giving Prince Khalid the real story because he did not want the Saudi army to be shown up as cowards and damn fools. I asked for a doctor and lifted my shirt so the air force officer who was interpreting could see my wound, but when they left I realized he had not told the prince anything about it. The prince was sitting on the other side and could not see for himself.

Prince Khalid and his retinue went off to inspect our airplane. After he left ,he had a soldier bring us a canteen of his private water. It was delicately scented with rosemary.

That afternoon, soldiers blindfolded us again, put us back in the trucks and hauled us two hours across the desert, right back to where the airplane was.

The prince had set up camp near the plane and we were taken to a tent of our own that looked like a stage prop from The Desert Song. It was striped in brilliant colors and it had padding and oriental carpets on the floor. During the afternoon, the soldiers brought up a few of our clothes which they had salvaged from the plane and spread them on the ground to dry.

Held prisoner by Saudi soldiers, the party of Americans waits anxiously in a tent to see what will happen to them. Members of the group are (left to right): Mrs. Kendall, Kathy, Susan, Paul, Mrs. Shearer, Stephen Shearer (standing) and the wounded Thomas Kendall. Two members of the party not in the picture are Bob Kendall and David Lees who took the photo. Soon after this the prisoners were flown to Jiddah and eventually released. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

We couldn’t believe our eyes when an American stuck his head in our tent and said, ‘Hi.’ He told us he was a Saudi Arabian Airlines pilot who had flown the prince down. This American pilot had been trying to get a chance to speak to us all day. He told us that the king was embarrassed and wanted to hush up the whole incident.

Soon the soldiers found the pilot talking to us and insisted he leave our tent. He gave us some vitamin C tablets which was all the help he could offer. Later we heard him arguing with the prince, trying to get permission to fly us out right away.

In the evening they turned on electric lights powered by a portable generator and fed us one great bowl of lamb and rice which we ate Bedouin style with our fingers. After nightfall there was a good deal of activity because during Ramadan the Moslems fast all day and then have a big feast after dark.

Our American friend had advised us to leave the lights burning in our tent, and all night long Bedouins came wandering in and out and peered at us through slits in the canvas. One of the officials who had visited us with the prince that morning said to me, ‘How come you got hurt? You weren’t hurt this morning.’

The prince slept most of Friday and we didn’t see him until the afternoon. In mid-morning a soldier brought us the first-aid kit from the airplane, but the bandages were soaked with sea water. The only thing usable was some weak antiseptic which we used to wipe off our wounds.

In mid-afternoon a plane arrived from Tabuk with an Egyptian doctor, and anaesthetist and complete field operating equipment. They had come prepared to do an abdominal operation in a Bedouin tent with sand blowing all over everything.

But after giving me a cursory examination the doctor said that since I was still alive, it was unlikely that I had a bullet in me. He painted my side with Merthiolate, slapped a bandage on, gave me a shot of penicillin and told me I was ready to travel.

With the American pilot’s assistance I hobbled down to the prince’s tent, with some reluctance, to thank him for his hospitality. I shook his hand with my left hand as I normally do, because my right hand was injured in an accident years ago. Afterward the pilot told me I had given the prince a terrible insult because Arabs use their left hand only for toilet purposes.

In one of Lees’ photographs before the attack, we see Kendall plotting a course from Luxor (the right arm of his dividers is at Luxor) in his aircraft. Here, we can see that there is something odd about the way he holds the pen in his right hand. Because he had injured his hand many years before, he was forced to shake Prince Khalid’s hand with his left, thus causing him great insult. Photo: David Lees, LIFE

At 7:30 we landed at Jiddah. Two limousines pulled right up to the airport ramp and whisked us away to the Kandara Palace Hotel nearby. We were held in seclusion at the hotel for five more hours of interrogation. All during that time we were denied the opportunity to make any telephone calls. The major interrogating us threatened to hold us there incommunicado ‘until such time as you have given us all the information we want.’ I finally got so furious that I refused to say another word.

Things were at a stalemate when suddenly, about midnight, U.S. Ambassador Donald Heath, his wife and several members of the embassy staff walked into our room accompanied by a high official of the Saudi Arabian Foreign Ministry, Sayyis Omar Sakkaf. Ambassador Heath routed his excellency out of a big end-of-Ramadan ball in order to force his way in to see us.

In the ambassador’s presence we told the full story of what happened to us. Then Mrs. Shearer and I were taken to the hospital for x-rays. The doctor’s report on me was a masterpiece of evasion: ‘One opaque F.B. [Foreign Body] of metallic density is seen in the abdomen at the lower pole of the right kidney at the level of the upper margin of the third lumbar vertebrae. Its shape resembles a bullet.’

In the 60+ Years since

When photographer Ken Stanford visited the location of Kendall’s wreck in February 1995, it was still in a recognizable condition, though heartbreaking to look at. Photo: Ken Stanford

Ken Stanford brings us a little closer to the decaying hulk. Photo: Ken Stanford

The sad remains of Kendall’s dream slowly dissolves under the onslaught of vandals and the caustic Arabian Sea elements. Photo: Ken Stanford

A haunting image of a dream that came to a sad end where the vast sand desert meets the blue Red Sea. We can see that the gear was deployed before it was lost. Photo: Ken Stanford

As Ken Stanford stands beneath the wing, we are given a sense of the large size of the once-beautiful Catalina. Photo: Ken Stanford

The weakening structure was still strong enough to walk on in 1996... not so today. Photo: Ken Stanford

The rear structure of the wing was gone by 1995. Photo: Ken Stanford

In 1995, the engines looked almost salvageable. Photo: Ken Stanford

In 1995, 35 years after the incident that stranded the once elegant Catalina on the shores of the Saudi Arabian coast of the Red Sea at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba, all the fabric that covered control surfaces has long since vanished. Though aluminium does not rust, it shows the effects of the corrosive environment. Some of the original paint remains as the clear registration—N5593V. Photo: Ken Stanford

Photographer Donald Curtis, who works in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, enjoys taking road trips in order to do some photography. This wonderful image of the remains of Kendall’s dream is strongly reminiscent of the superb work of Edward Burtynski—powerful, colourful and frightening all at the same time. Curtis tells us, “I had seen the Catalina many years ago when she still looked pretty pristine, although at the time I was not into photography so I decided to take a road trip to see how she was holding up. So I loaded up my truck and camera to get reacquainted. Well, as the pictures show, she was not holding up too well when we saw her. You see the elements, being next to the Red Sea, and the visitors were not kind to her as you can see she has been tagged with graffiti from every nationality imaginable. Nevertheless, she still draws attention from the curious and the troves of visitors she receives regularly.” Photo: Donald E. Curtis

A shot of the weathered remains of Kendall’s dream reveals that, despite more than half a century of exposure to a particularly harsh environment, the registration, N5593V, can still be clearly seen. If this was a Spitfire in this condition, it would be instantly retrieved and the process of returning it to the sky begun. Photo: Donald E. Curtis

The wreck of the old luxury flying yacht is far from any civilization, yet many have heard of her and make the trip out to pay her a visit, many with cans of spray paint in their cars to wound her once more. The big wing finally collapsed a few years back as the pylon and struts rotted. Photo: Donald E. Curtis

As late as the 1970s, the Landseaire promise was still alive. Here Horizons Unlimited sold membership in a Landseaire luxury flying yacht for outdoorsmen. This advertisement appeared in 1971 in the Ludington, Michigan Daily News.

We leave you now with a wonderful vignette related to us by one of our readers. As late as the 1990s, he experienced the wonder of the Landseaire in California.

“During the summers in Northern California my partner and I enjoyed water skiing on Lake Barryessa, mostly on weekends. The lake, which is a very popular water recreation area, is located about 100 kilometres northwest of Sacramento. On the day in question, some time in the early 1990s, we were out in the middle of the lake speeding along on a mirror surface when I heard behind me the drone of a familiar aircraft engine.

I was only recently on skis after the long winter hiatus so was a bit nervous but I was compelled to look over my shoulder to see if another boat was overtaking us.

Well, it was actually two boats in the form of a pair of PBYs coasting in a south to north direction about 500 feet elevation. Back in the 1950s, when I was in U.S. Naval aviation and air crew on an aircraft re-positioning squad, I did a lot of time in PBYs mostly between San Diego, Jacksonville and Pensacola. I was so enraptured with the sight that I forgot that I was supposed to hold onto the tow rope to stay afloat. I suddenly found myself treading water while the pair of aircraft passed directly overhead and banked right over the hills to the east.

My partner quickly picked me up and, by the time I was back in the boat, the pair once again approached and made another very low level pass. I instructed my partner to head for the shore as I perceived that the pilots were trying to clear a landing path in the lake.

They did indeed circle and then began a quiet glide making contact with the lake surface with a sudden typical power surge and white water spraying in a beautiful and reminiscent wake. They taxied over to the marina area and anchored. I just could not help but take advantage of a totally unexpected and rare opportunity to show off to my friend my knowledge of the aircraft.

We idled over to the now open bow hatch of the nearest craft of which a bare footed crew member in white yachting shorts and Hawaiian shirt emerged and asked if he and his fellow pilot could bum a ride to the marina. Needless to say that I quickly bargained a ride for a tour, so it came to pass that we experienced the luxury of a pair of Landseaire conversions, very much in stark contrast to the stark military interiors that I was accustomed to in the ‘good old days’.

We ferried the airmen to the marina where they ordered a massive amount of take-out and were soon back aboard their ‘ships’. We visited on board for a while sharing their ‘picnic’, exchanging war stories of flights of yore, rescue missions and sea borne medical evacuations. Both men were veterans of naval PBY operations. We departed vowing to keep in touch, but as passing strangers in the night, alas there was no further contact.

About 30 minutes later, the whole lake was alerted by the backfire of aircraft engines cranking over. After pre-flight check the boats taxied down to the south end of the lake, powered up and began their departure. It was a sight to behold these two dignified artifacts from the past gracefully lifting off in tandem and banking to the west in formation to finally disappear, lifting over the edge of the Coast Range. It was a breathtaking event that very few people witness, especially for an aged sailor who, for a brief moment, was made young again with the sight, sound and flight of two magnificent flying machines.

I am now 80 years young and I still get goosebumps thinking of that day.”

Frederick Harvey, aka The Navalator, from Golf of Siam, Thailand

The Dream Lives On

Despite the early broken dreams of Landseaire promoters, the dream lives on. Beach rocker Jimmy Buffet once owned a tricked out Grumman Albatross, but it is now retired and on display at the Orlando airport. It once received a similar treatment as Thomas Kendall and his Landseaire – having been shot at by Jamaican police who mistook it for a drug runner airplane. Photographer Leonardo Correa Luna has sent us some photographs of two restored flying yachts – a gorgeous Grumman Albatross amphibian and a Piaggio P.136 - a military flying boat from the late 1940s.

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

In service with the Italian Navy

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna

Photo: Leonardo Correa Luna