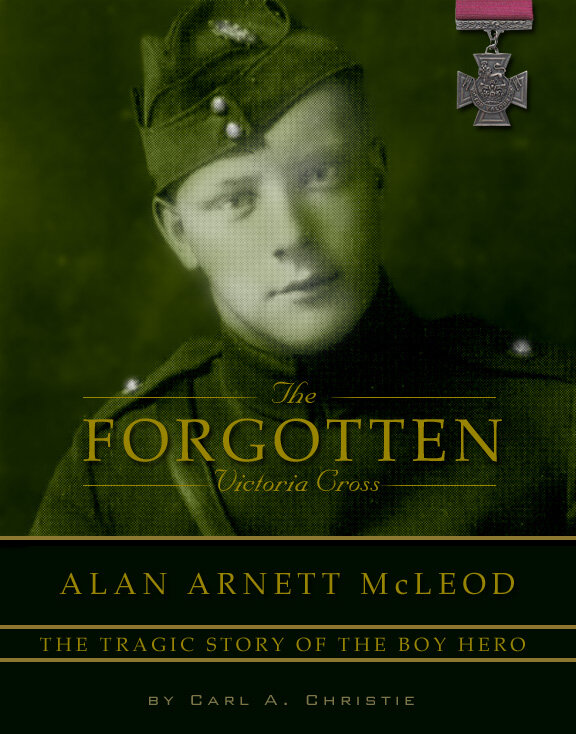

THE FORGOTTEN VICTORIA CROSS

During the First World War, there were three Canadian-born Royal Flying Corps recipients of the Victoria Cross. All three of them survived the actions for which they were awarded the Commonwealth's highest military honour. Two of them, through their exploits and the further exploitation of their fame, are remembered in Canada today - William George Barker and William Avery “Billy” Bishop. During the Second World War, four other Canadian airmen - Robert Hampton Gray, VC, RCNVNR; Andrew Charles Mynarski, VC, RCAF; Ian Willoughby Bazalgette, VC, DFC, RAF; and, David Ernest Hornell, VC, RCAF were awarded the Victoria Cross. Not one of them survived the actions for which they were cited, but thanks in large part to organizations like the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, the Canadian Naval Air Group, Vintage Wings of Canada and the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, they are remembered today.

However, the story of Alan Arnett McLeod, one of the three Canadian airmen awarded the Victoria Cross during the First World War, seems to have faded from our national memory. At just 18 years, he was the youngest of all the recipients mentioned above and his feat of flying combined with heroism should have given him a grander seat in the pantheon of our war heroes, but he is largely forgotten. Shortly, it will be Remembrance Day here in Canada and around the Commonwealth, so we would, with the help of military historian Dr. Carl Christie, like to honour this forgotten hero.

We would like to thank author, Carl Christie and the Canadian Aviation Historical Society in whose Journal his story was first published almost 15 years ago. The story is told largely through the chatty letters McLeod wrote and sent back home to his parents in Stonewall, Manitoba. At first the editor considered a major shortening of the story to appeal to the web reader, but Christie's account and story weaving are so compelling it has been decided to run it in its entirety. The McLeod letters reveal much about the maturity and courage of the boy hero of Manitoba. Read on now, right to the end, for that is where the tragedy lies and perhaps the answer to his fading from our consciousness. – Ed

Alan McLeod's story, as told by Carl Christie and published in the Canadian Aviation Historical Society Journal in 1996:

The son of a small-town general practitioner, Dr. Alexander Neil McLeod and his wife Margaret Lyllian Arnett, Alan McLeod hailed from Stonewall, Manitoba (a prairie town of less than 2500 souls even today, only a few minutes by car northwest of Winnipeg). Alan appears to have been typical of his generation and small-town upbringing, rambunctious and fun-loving, getting into occasional scrapes, but ever the apple of his parents' eyes. Young Alan loved the army, even managing to join the local militia cavalry regiment, the Fort Garry Horse, for the 1913 summer manoeuvres when he was only fourteen years old.

When war broke out in 1914, only Alan's age prevented him from enlisting. Developing an interest in the flying services, he tried to join the cadet wing of the Royal Flying Corps in Toronto but was told to wait until his eighteenth birthday, 20 April 1917. On that very day, he received a rousing send-off from his teachers and schoolmates. Catching the train in Winnipeg with his friend Allan Fraser, Alan almost immediately began a habit - writing chatty letters to his parents - that gave his family and succeeding generations a remarkably vivid picture of his experiences. They allow us to see the development of a keen, fun-loving teenager into a professional air force pilot. They also describe an era long since past.

Unable to sign up for action overseas, McLeod continued service with a militia cavalry unit known as the Fort Garry Horse which he had joined even before the war at the age of 13. No more than a 17 year-old boy in this photo, McLeod looks every inch a man. Photo: National Archives (NA) C-27812

The train trip to Toronto, the training he received, and other experiences yet to come must have been incredibly broadening for a small-town prairie lad. One is struck, however, by the way in which Alan McLeod appears to have taken it all in stride. He made friends easily and never had any problem getting along with people older than him, who always seem to have been impressed with his enthusiasm and easy disposition.

The letters reveal a typical young recruit away from home for the first time, with great fluctuations of emotion, sometimes excited by the great adventure he had embarked upon; sometimes wallowing in self-pity and extreme homesickness. On several occasions he was ready to pack it in. Only seven days after boarding the train in Winnipeg, he wrote from Burwash Hall at the University of Toronto, where RFC Canada indoctrinated the new recruits, that he had “been away a week today & most of it has been the most miserable week I have ever spent in my life.” A few days later he said, “the only thing that keeps us all going is the thought of flying.”

Interspersed with complaints of being lonely and homesick are some interesting observations about the training he was receiving and the organization he had joined.

“My the fellows are flocking in here like anything, there are hundreds of us now & believe me they aren't going to make all of us officers, they have some other plan behind it, the general opinion is that they will just pick out a few of the very best & make the rest into an infantry unit, because we have nearly a battalion now, there are many fellows here who have been aviators & can fly & everything but they have just come here to take up the military course of it & get to be an officer. I guess they will be the first pick ...”

He complained about the drill and was pleased when they reached, what in his view, were more practical military subjects. A few days into his course he told his mother:

“... to-day we had a very interesting lecture on the working of Lewis Machine Gun my it is a wonderful instrument of torture. After to-day I think we are going to take 2 hrs a day off drill for lectures, that will be nicer because I'm clean played out & my feet are very sore lugging these heavy army boots around, I haven't had time to break mine in yet.”

When he moved from the School of Military Drill & Discipline to the School of Military Aeronautics, still at U of T, he told his parents this involved lectures, with only an hour and a half of drill each day. His letters provide an insight into the curriculum. For example, “this morning we had lectures on Wireless, we have to be able to send 18 words per min & receive 12, we also had a lecture on the different types of Engines in aeroplanes, and my experience with Cars doesn't seem to help me any, everything is so different ...”

The lecturers were not always easy to understand, especially since, according to Alan, they were trying to cram an eight-week course into four:

“the instructors have no time to explain anything over again, and to-day an officer gave us a lecture on bombing and he talked so fast that we couldn't take it down, we were supposed to take it word for word and none of us got half of it, and we have all that stuff on exam next week I don't know anything about this dope, I am completely discouraged, that lecture got all our goats, the fellows are all sore & most of them have given up, they are rushing us so fast we haven't time for half the work, they expect too much of us, of course I'll keep on trying but I don't think for a minute that I'll get through and I don't care much for my own sake I don't care if I get through at all, I'm fed up on it and none of the fellows that are out at the camps flying like it, they all wish they were out & advise us not to pass, but I'd like to pass for the sake of you & Dad, I know you'd like it, but I can easily find some other good unit, as good as this if I fail so I'm not worrying.”

Related Stories

Click on image

He cautioned his folks:

“... perhaps I will be discharged, a lot of fellows have been put out, but it won't be my fault. You have to have a natural ability for machinery to stay in this and I certainly haven't. I should know more about a car than I do for the time I've been at it, but I'm sure going to work harder than I ever did before so if I fail it won't be my fault”

As he buckled down to his studies, he gradually sounded more confident:

“If a fellow gets through this course it will be great training for him, we are taking up map reading now, to qualify for an RFC Officer you have to be able to glance down at the ground and then glance at your map and know where you are at once ...”

The course content made him feel important, as he wrote on 11 May:

“We hear some very interesting things here about the air work at the front but we are not allowed to tell about it everything we have in our lectures is to be kept secret, because if we told it & the Germans got hold of it, such as secret codes etc, well they would have a better chance at the British planes.”

In the same letter he mentioned that another payday had come and gone, but he did not have much to show for it:

“Well, we got paid again today $3 and we were asked to give $2 for a life membership ticket to the Sports Club of the Aviation Corps and of course we couldn't refuse so that meant $1 left. Gee they don't overpay us anyway.”

A week later the pay was only $2, but he did not know why. His pay, $3 a week net after the deduction of $4.70 for messing costs from the supposed $7.70, also had to go to the purchase of textbooks that cost as much as $5, as well as incidentals such as laundry.

Notwithstanding some financial problems (for he only cleared a dollar or two a week), and some recurring depression, he gradually developed a pride in his corps:

“If a fellow is going to enlist, tell him to enlist into the RFC. You couldn't join a better unit. You are treated well, although there is lots of hard work connected with it.”

Finally, after letters in which he complained about his lack of comprehension in a variety of new subjects, like Astronomy and Photography, Alan addressed his "Dear Old Dad" on 2 June 1917 to say: “I passed my exams OK and I leave for Camp on Monday ...” If his enthusiasm was muted, his father quickly learned why:

“I suppose you heard Allan Fraser was killed last Thursday at Deseronto, flying with Vernon Castle, the papers said it was an air pocket they struck but the truth of the matter is that Allan lost his nerve and grabbed the control joice and upset them. My I feel awful about [it], I can't think of anything else and his poor parents will feel so badly, he only left last Monday for Camp. I think it was his first flight ... I got your letter this morning asking about Allan, it seems awful to think he's dead. I can't realize it.”

Contrary to his expectations, Alan went to Long Branch, just west of Toronto, and not to Deseronto in eastern Ontario. The first entry in his flying logbook is dated 4 June 1917, recording a 10-minute initiation flight. Then he was up for 35 minutes on each of the next two days. He loved the experience:

“Well I was flying for a while this morning again. Gee it was great. I took complete control of the machine, the Lieutenant said that I did really well, so there is some chance that I [will] become an aviator. I feel as much at home in an aeroplane now as I do in a car. Gee it's great, travelling 200 miles an hour on a nose dive, it's some sensation, when you hit the ground for landing you are travelling about 75 miles per hr. but you never realize it unless you saw the speed indicator.”

Everything took second place now to his new love, flying.

“I had a great flight to-day,” he wrote home on 7 June, “I raced with a train, there was an instructor in the back seat though, I sure think it's the greatest thing out to fly it's certainly grand. I just love it, but it makes you awfully tired, so they don't work us hard, we lie around most of the day.”

On 9 June, after a grand total of six flights and 2 hours 15 minutes of dual instruction recorded in his logbook, Alan McLeod went solo. The exhilarating experience inspired him to try it again the next day. He described both episodes to his father:

“I did my solo flight yesterday. I made a bombing success of it and did really well, but I made up for that this morning. I thought I'd try another solo, so I went down to the Hangars and told the mechanics to pull out 162, so I went off fine and flew around for a while but it was so bumpy, I couldn't stay out, first the machine would dive and then it would nose up, so I thought I had better land. I was up at 3,000 ft and shut off the engine and began to glide for the aerodrome, but for some unknown reason, I misjudged the distance and landed behind the flag instead of in front. I struck hard ground and landed too suddenly. I smashed all the wires on the undercarriage and nearly broke the propeller, but the machine was fixed in about 1/2 hr. Another fellow went up and smashed his machine up pretty well, but got away unhurt. After we have our solo, we can take a machine and go up any time we like and we don't have to go up unless we want, they never say anything to you for smashing a machine. I guess I'll try again this afternoon and make a good landing, this is Sunday but we have to work all the same, but we never work very hard.”

Alan took to the flying at Long Branch with great gusto and, with his share of mishaps along the way, picked up as much experience in the air as he could. On 12 June he gave his father a pretty good idea what it was like:

“I like it here fine, the flying is great, they didn't give some of us enough instruction and as a result we broke a few machines by making bad landings. I had a crash yesterday. I didn't know the wind had changed and I came down with it, instead of against it and smashed the plane all up, but the O.C. just laughed and said "that was a fine landing" they never care if you have a smash, if you didn't they would think there was something seriously wrong, it is impossible to hurt yourself when making a landing. You may smash the machine but you can't get hurt, the only way you can get hurt is to fall from the air and you can't fall unless you try stunts and I tell you I am mighty careful. I got lost yesterday. I was up for a long time and I couldn't find the aerodrome, I flew right over Toronto but I didn't intend to, at last I followed the Lake Shore till I found the Drome.”

The next day he admitted that flying was not always fun. “Well I got up early this morning and went for a fly. Gee it was Bumpy, the plane would jump all over the place, but it's not dangerous, the flying is not bad but it's tiresome sitting up there and flying all the time, half the time I want to sleep, but it would hardly do.”

On 17 June Alan's logbook recorded an accumulated total of 10 hours 20 minutes in the air, 5 hours 10 minutes of that solo. With that he was transferred from Long Branch to Camp Borden to learn about aerial gunnery, wireless, and other necessities of military flying. It did not take him long to develop the usual trainee's appreciation of this establishment. On 19 June, he called Camp Borden “the rottenest hole I ever landed in except Oakville Manitoba.”

On 22 June he had a frightening experience:

“I had a rather exciting time this morning, about 4.30 this morning I went up for a flight with three others, the air looked rather misty but we didn't think anything of it, but as soon as we got about 100 ft. off the ground, we couldn't see a thing it was all mist, you could only tell by feel whether you were going up or down or side slipping or how you were going. As soon as I saw this I thought I would go to the aerodrome and land but I couldn't find it. I flew around for about 1/2 hour and at last through a spot in the mist I saw land, but not very clearly. I wasn't going to float around so I came and landed, and when I got down I found I was only about 1/2 mile from the aerodrome so I just ran the machine in. I was sure thankful to get to the ground, one of the other fellows landed in a field about 20 miles away, another fellow crashed his machine in a swamp and isn't back yet, the other fellow landed in another field about 10 miles away 1 fellow just got back now and it is 12 o'clock - the other two aren't back yet, they all phoned in. I was the luckiest of the bunch. Gee I was scared.”

The account to his mother was much shorter, concluding with the observation, “Gee it was some sensation flying around and not knowing where you are going. I was thankful when I hit dry land.”

He was trying to get in as much flying as possible. Near the end of June he wrote following an early morning flip: “I have just come down from a nearly two hour flight, when you once get a machine here, you have to hog it, or you won't get your time in.” Much of the glamour seems to have gone and a certain amount of drudgery was creeping in: “I like the air pretty well, but it's tiresome sitting in a machine and riding around it gets monotonous.” Still, he was obviously feeling comfortable in the new world he had entered and was proud of it. “I think no more of getting in an aeroplane and going for a ride to a town 50 or 60 miles away that I thought of going for a ride around town in the Maxwell.”

As he gradually added flying hours to his logbook, and developed his machine-gun and wireless skills, he started to write about rumours of going overseas. He found this frustrating, increasingly longing for a period of leave back in Stonewall and an operational posting. He had mixed emotions in July when made an instructor to other young pilots. Speculation about an overseas posting crept into virtually every letter by this time.

On 4 August he described his life at the School of Aerial Gunnery to his sister, Helen, and concluded with a general gripe: “My I wish they would hurry and send us overseas and give us our commissions, we don't know what the delay is, but there is so much red tape in the army, you never know where you're at.”

Five days later he told his mother, “I received word that I am going over in the next draft, whenever that is, it may be a year and may be a day for all I know.” The prospect did not thrill him: “I am very sorry I'm going on it because I'll have to leave all my friends behind.” And he would not see action immediately: “... we were told we would probably be a long time in England, might not get to France till next spring because there is no flying in France in the winter time.” Then he cautioned, “of course that is not official so don't take it to heart.” The same day he repeated the old refrain to his father: “I hope I get leave to come home, but of course I have no idea whether I'll get it or not. I can only hope for the best.”

McLeod peers over the coaming of a JN-4 trainer while taking instruction with the 90th Canadian Training Squadron at Leaside, Ontario. This was the summer of 1917 and the Leaside facility had just been completed for the Royal Flying Corps, but today all traces are gone in this suburb of Toronto. Frank Ellis photographed McLeod sitting in the front cockpit. Photo: Frank Ellis

At this point there is a gap in the correspondence. However, things must have happened very quickly. The next letter was written on an eastbound train at Kenora (in northwestern Ontario) on 15 August, after he had spent some time at home. Second Lieutenant Alan McLeod, RFC, with 43 hours 5 minutes solo and 6 hours dual on his pilot's flying logbook, was off to war. He embarked at Montreal on 20 August 1917, exactly four months after leaving his grade XII class in Stonewall.

Alan had a couple of shocks when he arrived in Britain. He wanted to start flying right away but had to spend ten days leave in London. He found this expensive, complaining that “the prices of things are simply awful £1 goes as far here as $1 in Canada ...” In this economic environment,

“I got my outfit allowance yesterday it [is] only $120 not $200 as we were told at Borden and this will barely cover the things we need, we have to buy a trench coat $25, Goggles $10 and we have to buy our own blankets bed & pillow, it's really awful, these were the things we were supposed to buy and then were supposed to buy a new uniform for dress reasons they don't wear this kind over here, but I'm doing without most of those things, I don't know whether they'll say anything or not & I don't care, we get $2.50 a day and we'll have to pay $1.50 for mess etc so I'll have $1. a day clear ...”

In this, his second letter from the U.K., he seemed happy to report his first war experience:

“I was in the Theatre last night with another fellow and the Germans started to Bomb London, and some one came in and asked for all Flying Corps Officers and we had to go on the streets and keep the people into the underground passages, I was right near where one bomb dropped, right on Charring [sic] Cross near the Savoy Hotel, there was some excitement for a while, but the people here are beginning to take it as a matter of course, there has been a raid every night since we [have] been here.”

He was also disappointed that 82 Squadron, to which he reported at Waddington, near Lincoln, on 14 September, “don't expect to go to France till spring ...”

Along with courses at other RFC bases, such as the Wireless and Observers' Course at Hursley Park, Winchester, Alan spent several weeks at Waddington, learning to fly "Service Machines," one of them the “big A.W. [undoubtedly the Armstrong Whitworth F.K. 8, which he dubbed] the flying tank, they weigh about 5,000 lbs ..." Perhaps presaging how he would fly the FK8 on squadron service, he commented, “they're some bus. I looped one the other day. I was the second person here to do it, they're perfectly safe but people did'nt know it, you'd think you were riding in a parlour car they ride so smooth, but I'd much rather fly a smaller machine, they are easier to stunt with.”

He got his opportunity to demonstrate his skills at the controls of the lumbering old bus, the FK8, when he was finally posted, after initially being forced to remain in Britain because of his tender age, to Hesdigneul, France, to join No. 2 Squadron of the RFC. He reported on 29 November and made his first flight the next day.

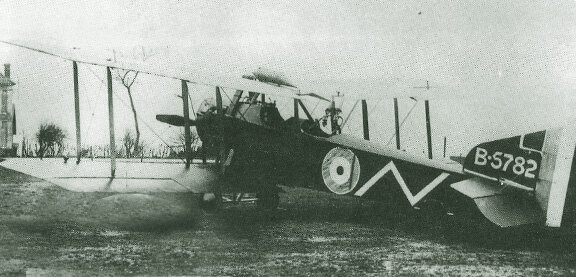

The lumbering Armstrong Whitworth F.K. 8 “Big Ack” was designed for the same role as the R.E. 8 (“Harry Tate”). The aircraft, originally designated the F.K.7, was designed by Dutch aircraft designer Frederick Koolhoven as a replacement for the Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c and the Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3. The type was unusual in having dual controls, enabling the observer to control the aircraft in the event of the pilot becoming incapacitated by enemy action. The F.K.8 served with several squadrons on operations in France, Macedonia, Palestine and for home defence, proving more popular in service than its better known contemporary the R.E.8 Photo: Wikipedia

He was quick to reassure his folks after his arrival on the continent:

“We are not very far from the front line trenches & we fly over them every day, we can hear the Guns going all the time, they seem to be having a rough time out there. Just to let you know how safe I am I'll tell you that the Squadron I'm in has only had 1 man killed in the last 6 months and he killed himself by doing a fool trick with his machine, the casualties in the RFC. in France are a great deal less than they are in England & in Canada, in proportion, why take at Borden 6 were killed one week, so I know you won't worry now you know how safe I am.”

He appreciated what he viewed as his favoured position as an RFC officer. He told his mother that instead of sending so many parcels to him, she should “send the ones you would send to me to the fellows in the trenches ... [they] need them a thousand times more, we have a cinch compared to them poor fellows ...”

Early in the new year he went into some detail as he tried to convince his parents he was safe:

“Say please don't take it so seriously about me being in France and don't worry about me. I'm in practically no danger whatever and I'd rather be here than in England anytime. In the R.F.C. after a Pilot has done 3 weeks or a month in France and is still alive he's considered safe for the rest of his time in France. 95% of the Casualties in the R.F.C. are new Pilots out in France that don't know the ropes and in their first two or three trips over the lines they're done in because they are so inexperienced; but after your first bunch of trips over the line you begin to get cunning. You know the ropes and then your [sic] safe, do you know that in an official list of Casualties in the R.F.C. that came out the other day, it showed that there are more pilots killed in training in England than there are in France in the same time, we have a regular safety first job out here, this Squadron has had 2 casualties in two years, so you know I'm in no danger whatever so don't be foolish and worry over nothing.”

Later in the same letter he bragged, “this is the crack squadron of France, and anyone who isn't up to the mark gets kicked out.”

The tall and lanky McLeod (third from the left) stands proudly with his squadron mates sometime before his action.

For the most part Alan's letters from France talk about his impressions of the country and its people, as well as the social life of the squadron. Quite understandably there is little detail on his flying activities, save comments on the cold and the boredom.

The boredom was broken on 19 December 1917, when Alan attacked eight Albatros scouts. His observer claimed to have shot one down. Then, on 12 January 1918, he and his observer, Lieutenant Reginald Key, claimed a kite balloon and an Albatros. In the words of his squadron commander, “he attacked a hostile balloon near BAUVIN. This appeared to collapse and was seen to fall rapidly.” Major Snow concluded his letter to the Officer Commanding 1st Wing with a general comment on 2/Lieut. A.A. McLeod: “He has shown keenness in his work, and I regard him as a most capable and reliable Artillery Pilot.”

Some have wondered if Alan McLeod should have been a fighter pilot. Certainly that appears to have been the role he would have preferred to play. And play is the operative word, for he spoke of “playing the game.” For him the whole experience seems to have been an extension of the playing fields of Manitoba.

Not much more than two months after attacking the kite balloon, McLeod, flying with Lieutenant Arthur Hammond - who had become his observer when Key was posted out - committed the act that gave him his place in history. Flying in support of Allied armies during the great German offensive, McLeod and Hammond were just about to drop their bombs when they spotted a Fokker triplane. No sooner had Hammond shot it down than they themselves were attacked by seven more members of the Richtofen Circus. Hammond sent at least one down in flames, but the FK8 was raked with fire from behind and below. The old bus was hit in a number of places and burst into flames from the fuel tank in front of the cockpit. Had aircrew worn parachutes in those days, McLeod and Hammond may have chosen to jump. As it was they had to ride the aircraft down (from a height estimated at anywhere between 2,000 and 6,000 feet) as best they could. In a 1920 letter to Alan's mother, Hammond described the incident:

“...during this time we were side slipping and Alan was standing up with one foot on the rudder bar and the other outside on the wing and I was standing on the bracing wires at the side of the fuselage as the bottom of my cockpit had fallen out and as we neared the ground I climbed out on the top wing so that when we hit the ground I was thrown forward on the ground. I saw Alan jump out of the machine and look for me but he evidently thought that I had fallen out.”

This is consistent with other reports that Alan claimed the worst part of the whole experience was his initial fear on crash-landing that his friend and observer had fallen from the fire-ravaged plane.

An AW F.K. 8 reportedly the machine that McLeod was flying the day he was shot down. Destroyed by fire and the crash, it carried them safely to ground in No Man's Land and into history. Photo: DND

A full colour profile of the AW F.K. 8 flown by McLeod on the day of his last action. Illustration by Bob Pearson For more profiles and great illustrations of Canadian aircraft and ships visit Bob's website: History in Illustration

Hammond continued:

“He came to me and tried to pull me towards our lines but it was too much for him so I found I could roll and with his help I rolled to where some of our own Infantry [in fact, a South African unit] took us to a trench. I afterwards found out from Alan that he was again hit while rolling me along the ground and I can remember hearing a machine gun firing quite close to us. We laid all that afternoon in the trench and that was I think, the worst experience of all, especially as the Infantry seemed to expect that the Germans would advance and take us all, but as soon as it was dark enough we were taken away and I don't remember any more after that and I came to in hospital and I never saw Alan again until we were both in England, and then to my surprise, he was very bad.”

A marvellous painting by Merv Corning depicts the action for which McLeod was awarded the Victoria Cross. McLeod sideslips the burning "Big Ack" to keep the flames from the rear fuselage while standing on the port wing root. In the rear, Hammond continues the fight. While the painting differs slightly in detail from the author's account, it does indeed capture the drama of the event. Image via CAHS and Leach Heritage of the Air Collection, 1963

In fact, Arthur Hammond had been hit six times; Alan McLeod five, in the neck and heel. The observer lost a leg, but otherwise made a complete recovery.

On 1 May 1918, it was announced that Alan McLeod was being awarded the Victoria Cross, Hammond a bar to his Military Cross. Discounting Alan's assurance that he was "fit as a fiddle," Dr. McLeod left his practice in Stonewall to be at his son's side in England, helping in his convalescence and accompanying him when he hobbled to his VC investiture at Buckingham Palace on 4 September. Dr. McLeod took his son home at the end of September.

What a difference a year makes. On the left, the youthful and soft-featured McLeod at 18 years, and on the right, a thin and weakened McLeod (19 years) after he received the Victoria Cross (ribbon is just below his wings) in London. When McLeod joined, he wore the uniform of a Royal Flying Corps officer and here he wears the uniform of the Royal Air Force (created just four days after his VC action). His continuing weakened state may have played a part in his succumbing to influenza in 1918. Photo: RAF

A Canadian military paper features a photo of a teenaged Alan McLeod recuperating in his hospital bed in England where he was joined by his physician father. He certainly looks healthy and happy. Little did he know, he and his father would face the most dangerous enemy upon their return home to Manitoba - the 1918 influenza epidemic. In short order he would be struck down, perhaps weakened by his injuries suffered in battle.

Manitobans embraced their young hero, welcoming him enthusiastically and reacting with devastation when he contracted influenza and died on 6 November 1918. With some irony, The Winnipeg Free Press reported the armistice in Europe on the same day that it covered the funeral of Alan McLeod. Side by side on the front page were the stories representing two extremes of human emotion.

In his too short a life Alan McLeod made only one significant contribution, but what an achievement it was, becoming Canada's youngest winner of the British Empire's highest award for gallantry, the Victoria Cross. In the process he must have been a good ambassador for Canada, because after the Great War Reginald Key and Arthur Hammond both immigrated to their former pilot's native land.

The boy hero of Stonewall, Manitoba is laid to rest in Winnipeg. Alan Arnett McLeod, VC died from influenza just four days before the signing of the Armistice. Being a physician, his father was most certainly devastated. Upon his return to Winnipeg in September 1918, he was taken on strength with the RAF staff.

About the author

Carl began working with the Department of National Defence's Directorate of History in 1977, where he joined the team of historians working on the official history of the RCAF. After researching and writing historical narratives on Canadian contributions to Ferry Command and the air force involvement in the Battle of the Atlantic, as well as serving as secretary of the editorial committee for The Creation of a National Air Force, volume two of the series, he accepted an offer to assume responsibility for public service as Senior Research Officer in 1987. In 1998 he moved to Winnipeg, where he has taught undergraduate and graduate military and aviation history courses to Canadian Forces' personnel on behalf of the Royal Military College of Canada. For three years he led the University of Manitoba, CDSS graduate seminar, 'Armed Force and International Security.' Today he is concentrating on finishing a one-volume history The (Royal) Canadian Air Force for the University of Toronto Press, making his annual presentation on RCAF history to the Command and Staff Course at the Canadian Forces College in Toronto, and writing his regular 'Humour Hunt' column for Legion magazine.

The editor of Vintage News would like to thank Carl Christie for allowing us to reprint this story as well as Tim Dubé, of Canadian Aviation Historical Society for suggesting this story and introducing us to Carl. As well we thank Vern Vouriot for his assistance in editing and proofing our stories.