THE GAUNTLET

The story begins on May 19th, 1941, when I was nine days out of Halifax en route to Britain. Until now my learning experience had been great fun and excitement, but war still seemed a distant fantasy; today it would become a reality. On the morning of May 10th, 1941, four of our group had been ordered to stand by for departure, Bill Wallace, Jack Milmine, Wally McLeod and myself. Driven to the Halifax docks, I was surprised that only our little group boarded the launch which soon pulled alongside the S/S Nicoya. The Nicoya, built for the banana trade in 1929, was listed at 5,400 gross tons, 3,300 net tons, 6,300 deadweight tons, with a coal-fired reciprocating engine. She was 400 feet long, 51 foot beam, 26.9 foot draft, and to me appeared small for an Atlantic crossing. Although there was accommodation for twelve passengers, there were only two others aboard, an RAF Squadron Leader, who was returning to Britain following Purchasing Commission duties, and his wife. The two capacious refrigerated holds were filled to capacity with butter and bacon. On deck were two large crates, each containing a Hawker Hurricane from Canada Car and Foundry at Fort William

As always in Service life, rumours abounded about our convoy; although we ate our meals and talked with the ship’s officers, the rumours were neither confirmed nor denied. Much of the information that is now available came from the Archives. When we sailed the next day we became part of convoy HX-126, comprising 31 ships formed up in nine columns, five of three ships and four with four ships, a formation designed to keep beam exposure to a minimum. Although our ship was rated at 13.5 knots, later calculation showed our average speed had been 6.72 knots. We appeared to be without escort, although rumour had it that the relatively small passenger vessel on the far side of the convoy was an armed merchant cruiser. This turned out to be correct; the vessel was HMS Aurania, (later changed to Artifex), a converted Cunarder. A second rumour, scoffed at at the time as ridiculous, was that we also had a submarine as escort. Strange as it might seem to have a submarine escorting a convoy, we later learned that HMS Tribune, a T-class submarine, had in fact been with us throughout our ordeal. Also unknown to us at the time was that the Aurania carried about 200 passengers, probably including the rest of my course from Camp Borden.

SS Nicoya, the cargo ship that successfully carried young Bill McRae and three compatriots across the Atlantic to a war that ultimately only McRae would survive. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

One of the surface ships assigned to protect McRae's convoy was the armed merchant cruiser/passenger vessel RMS Aurania, a former Cunard liner. Later in the war, Aurania would become HMS Artifex, a Royal Navy repair ship. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

HMS Artifex, formerly Aurania of the Cunard Line would end the war as a repair ship of the Royal Navy. Launched as the Cunard liner RMS Aurania she was requisitioned on the outbreak of war to serve as an Armed Merchant Cruiser. Damaged by a U-boat while sailing with an Atlantic convoy, she was purchased outright and converted to a floating workshop, spending the rest of her life as a support ship for the navy. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

Three days out of Halifax two ships turned back with engine trouble, leaving 29 to experience the coming disaster. The Nicoya was second ship in column nine, on the right flank. I thought to myself that this made us a prime target for torpedoing, and I wasn’t far wrong. We four airmen were assigned action stations in the event of an alert; mine was to assist our one RCN naval rating whose job was to operate the vintage 3” (or 4”) naval gun mounted at the stern. I was to operate the Lewis gun, mounted without sights on a post and swivel. Except in books I had never seen a Lewis gun! As we plodded along it was becoming obviously colder every day, indicating that we were probably sailing northeast. In fact when all hell broke loose we were at approximately 57° N, 40° W. I could not shake a feeling of impending disaster, knowing the water was infested with German submarines, a concern not helped by the streams of flotsam and jetsam that now began to pass us almost hourly. There were planks, boxes, life belts and one day an empty lifeboat, forming a sort of highway of wreckage across the ocean. It is likely this came from convoy OB-318 which had lost nine ships in this area the previous week. Obviously we were sailing into dangerous waters.

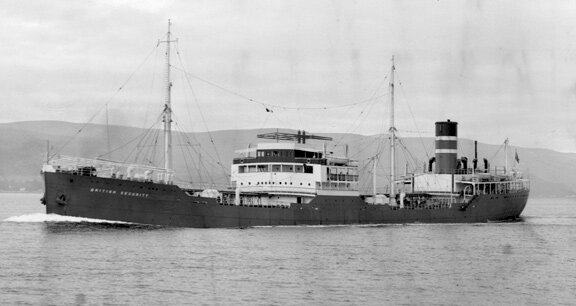

Around midnight Halifax time on the 19th, Wallace and I were sitting on the edge of our bunks talking when we heard a dull thud, and then our ship heeled over as we swung sharply to port, out of our column. The steward came down to summon us up on deck, where we assembled in the tiny wardroom to be informed that the ship directly in front of us in our column, the S/S Norman Monarch, had been torpedoed. Loaded with iron ore, it had gone down almost immediately, and our ship had to turn hard to avoid a collision. She had fallen victim to U-94, which also sank a second ship that night, the British Security, before losing the convoy in darkness. We were now lead ship on the right flank. The steward brought up blankets and pillows, instructing us to sleep in the wardroom with our clothes on; this was to continue for the rest of the journey. Nothing further happened that night. Next morning we were out at dawn at our action stations, all eyes scanning the water for signs of submarines. About noon the U-556 found us and in two attacks lasting less than an hour had sunk the lead ship in columns 7 (Darlington Court) and 2, (Rothmere) and had set ablaze the Elusa, a tanker, in column five.

Related Stories

Click on image

Norman Monarch, the first ship torpedoed as McRae and Nicoya entered the kill zone mid-Atlantic on their way to Great Britain. She was a British Cargo Steamer built in 1937 and of 4,718 tons. She carried a cargo of 8,300 tons of wheat when she was torpedoed by German submarine U-94 and sunk about 200 miles south-southeast of Cape Farewell. Crew of 48 saved. Photo of Norman Monarch at Cape Town, South Africa via www.photoship.co.uk

British Security, a tanker, was torpedoed whilst crossing in Convoy HX 126. She was a British Motor Tanker of 8,470 tons and built in 1937 by Harland & Wolff Ltd, Govan, Yard No 974 for the British Tanker Company. Carrying a cargo of 11,200 tons of benzine and kerosene when she was torpedoed by German submarine U-556, she sunk south of Cape Farewell. The master, 48 crew members and four gunners were lost. Photo: National Museums of Northern Ireland

Darlington Court, 4,974 tons, carrying Hurricane fighters on her decks, was sunk by U-556 with the loss of 25 sailors - 12 survived. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

Rothermere was carrying a cargo of 1,998 tons of steel and 4,750 tons of paper when she was torpedoed by German submarine U-98 and sunk 300 miles SE of Cape farewell. 22 crew lost from a total of 56. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

The tanker Elusa, was a British Motor Tanker of 6,235 tons built in 1936. She carried a full load of gasoline when she was torpedoed by German submarine U-93 and sunk. Photo via www.photoship.co.uk

U-556, seen here coming alongside Tirpitz, mauled Bill McRae's convoy.

A ship which had been sailing two columns over, with the fuselage of a Hudson bomber lashed to the deck, was gone, but the fuselage was bobbing on the waves like a stranded whale. (I later learned that the crew had cut it loose when they were torpedoed, hoping it would float and could be used as a raft!) The convoy was now beginning to scatter in all directions. I was watching helplessly when, with a swirl of foaming water, the bow of a submarine burst through the surface, about 50 yards away. Our gunner had already loaded the 3", and I now joined him in trying to crank it down to bear on the sub. For some reason, unfathomable at the moment, the Captain was yelling at us through a megaphone "Don't fire, don't fire!", but in any event we were unable to depress the gun far enough. With our later confirmation of the friendly submarine in our midst, the presence of which would have been known to our Captain, it became obvious he had wanted to avoid a possible error. The next thing we knew the sub had dived again, without having completely surfaced. Moments later there was a heavy thump and a violent shudder ran through our ship. Believing we had been hit, the Captain blew the abandon ship signal, let off all steam to prevent a boiler explosion if we flooded, and we coasted to a stop.

HMS Tribune, accompanied the convoy while crossing the Atlantic and quite possibly was the submarine which was spotted by Nicoya and Bill McRae

Shouting through his megaphone, the Captain ordered us to take up boat stations, lower the boats to the rail (there were four) but not to get in until instructed. Meanwhile the Chief Engineer was below decks looking for damage, but after a long absence returned to report he could find none. It took over an hour to get up enough steam to get under way again, and during all this time we stood by our lifeboat staring out at the wreckage and the still burning tanker, all that was visible of our convoy, expecting any moment could be our last. There was still time for a laugh, however. Each of us in our rush to the boats had taken only one possession, our log book. In my haste I dropped mine and managed to smear it with salt water, leaving a stain that has lasted to this day.

Our ship having been built for the fruit trade was possibly as fast as any in the convoy. The crew now worked up to maximum speed and kept it up for the rest of that day, all the next and into the third when we caught up with what was left of the convoy. At dusk on each of the days we were running alone the lookout in the crows nest called out `destroyer astern’, then, as last light set in, he changed this to 'submarine astern’. We of course thought it was a German sub tailing us on the surface expecting us to lead it back to the convoy, which we did. But it could also have been the Tribune, the presence of which had not yet been revealed to us. The Admiralty, realizing that our convoy as well as four others then in the North Atlantic were threatened by the German battleship Bismarck’s presence, had ordered our convoy to detour from the planned track; this may have contributed to the length of time it took us to rejoin. When we did I noticed the liner was missing and assumed she had gone down, but later learned the story. After avoiding two torpedoes she had, perhaps accidentally, rammed a submarine, suffering damage to the bow requiring immediate attention. She had run for Iceland where the airmen were put ashore. This resulted in the rest of my course reaching Britain two weeks after I did, and possibly changed the whole course of my war.

While we proceeded on our own, ahead of us U-boats U-94, U-98 and U-111 had joined up with U-556 in pursuit of the convoy and each sank another ship on the 21st. Ironically, one of these was the Harpagus, which had been third in our column. She had stopped to pick up the crew from the Norman Monarch, the first ship to go down. This left Nicoya as the only survivor from column nine. On the 22nd four more U-boats arrived to join in the hunt, U-46, U-66, U-74 and U-557, bringing the total submarine force to eight. Fortunately, contact was lost before further damage could be inflicted.

Not long after we had rejoined the convoy a flotilla of naval vessels loomed up on the eastern horizon, including the battleship King George V, the carrier Victorious, cruisers Galatea, Aurora, Kenya and Hermione and destroyers Active, Punjabi, Nestor, Englefield, Intrepid and Lance. I naively thought they had come out to protect us, but as events unfolded it became clear this was the fleet in pursuit of the Bismarck. There was an exchange of lamp signals and we were told later that we had been within two hundred miles of the Bismarck when she sank the Hood. Had it not been for the Hood, which we never saw although it passed us in the night, it is quite possible that within a few hours the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen could have intercepted and wiped out convoy HX-126.

Bismarck, the Kriegsmarine's massive battleship posed a staggering threat to convoy HX-126 if she wasn't stopped. She would have been able to destroy every ship in the convoy if their paths met.

There remained the puzzle of what had happened to our ship to make us believe we had been hit. Our Captain felt that either we had run over the sub which surfaced practically underneath us , or that we had been hit by a dud torpedo. He planned to go into dry dock at the end of the voyage, to have the hull checked. The official report on HX-126 acknowledges nine ships sunk and two damaged. The Nicoya was possibly considered as one of the latter. The remainder of the journey passed without further incident and 21 days after leaving Halifax we dropped anchor in the Mersey in front of Liverpool, but were not to disembark until the following morning. That night there was an air raid, probably one of the last of the heavy night attacks on the city. Through the porthole (we were not allowed topside because mines were being dropped into the harbour) we watched the Luftwaffe's work for the first time. The sky was filled with anti-aircraft bursts and flares; we could hear the crashing of bombs, and see the flash as they exploded. I had visions of having survived a torpedo attack only to be sunk in Liverpool harbour, but nothing fell near us.

Anyone noticing us as we went ashore the next morning must have wondered, when they saw four lonely Canadians coming ashore: "Is this what they're sending to help us"! We were an odd assortment; the emaciated appearing one, Milmine, weighing about 130 pounds soaking wet; the tall, gangling one whose left foot seemed to be going west and his right east while he walked north, that was Wallace. Then there was the short one with freckles and a shock of black hair, wearing a new trench coat which the salt spray had already turned from Air Force blue to the shade of an almost ripe Saskatoon berry, that was me. Only McLeod with his piercing eyes and fiercely determined expression looked much like a fighter pilot, and a deadly one he would turn out to be. Little did I realize at that moment that of the four I would be the only one to survive the war.

Almost a year after this close call, Nicoya met her end. On May 12, 1942, she was torpedoed and sunk by U-553 in the St. Lawrence River off Cap de la Madeleine, Gaspe, Quebec., the first loss in the Battle of the St. Lawrence. Nicoya was sailing alone when attacked close to the coast of the Gaspe Peninsula south of the western end of Anticosti Island at the point where the St. Lawrence River flows into the Strait of Honguedo. U-553 was commanded by Karl Thurmann, who launched his attack (in quadrant BB 1485) at 0552 (Central European Time?). The torpedo(s) struck Nicoya at 0355 (GMT?), and she sank at 49°19 North, 64°51 West. Six crew members were lost.