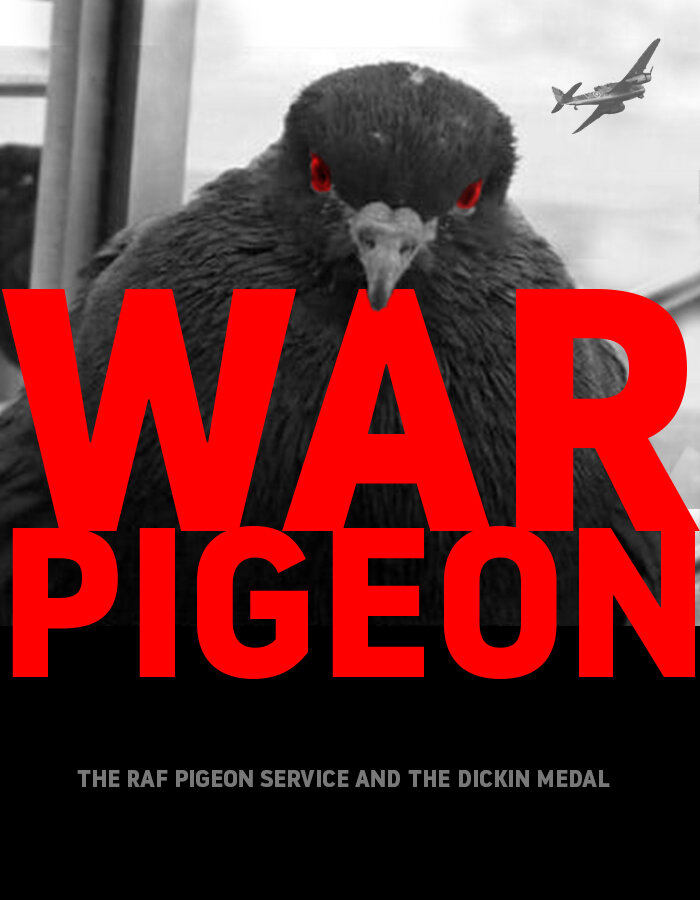

War Pigeon

The RAF Pigeon Service and the Dicken Medal

For as long as humans have, in their infinitely selfish wisdom, found it necessary to go to war, they have also conscripted innocent and unwitting animals to accompany them into their war hells—to carry their equipment, to support their knights, to track their enemies, to make their suicidal charges, to sniff out their insidious mines. From Hannibal and “Elephant Bill” Howard's pachyderms to Sir William Marshall's charger and the Light Brigade's plunging steeds to the terrifying Alsatians of German PoW camps and even the mythical Rin Tin Tin who was rescued from a First World War battleground, animals have played a huge part in the story of warfare.

More than eight million horses and untold mules and donkeys died horrific deaths in the First World War alone. We lionize (animal pun not intended) massive and shaggy hoofed warhorses in film and literature, but turn our heads at the sight of hundreds of dead and bloated horses still at the harness in some catastrophic scene on a narrow road behind the lines at the Somme or terrified and whipped mares dragging artillery pieces through the mud at Passchendaele. Even in the Second World War, the highly mechanized Germany army put three million horses to work, 750,000 of which were killed.

The out-of-all-proportion part played by animals in our horrid and obscene wars may get little notice in those great historical tomes war gives birth to, but there are those people for whom their actions mean much. One such person who felt that animals who were forced to participate in wars should be recognized for their contributions was Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin, a British social reformer and animal welfare pioneer who had previously founded the People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (a charitable veterinary service in the UK). She came up with the idea of a decoration for animals known today as the PDSA Dickin Medal to honour animals who served meritoriously in the Second World War. The decoration has often been called the “Victoria Cross for animals”. Truth be told, the Victoria Cross Trust is not particularly happy with the comparison.

The medal itself is a bronze medallion, bearing the words "For Gallantry" and "We Also Serve" within a laurel wreath, carried on a ribbon of striped green, dark brown, and pale blue. It is awarded to animals that have displayed "conspicuous gallantry or devotion to duty while serving or associated with any branch of the Armed Forces or Civil Defence Units". Originally created to honour animals for the ongoing Second World War, the Dickin Medal is still being awarded to this day, with the last recipient a Belgian Malinois (similar to a German Shepherd) by the name of Kuga that served with the Australian Army and Special Air Services Regiment (SAS) in Afghanistan. Kuga was shot five times in action with the SAS in the Afghan War and died of wounds after being airlifted first to Germany for surgery and then to Australia for rehabilitation.

One would imagine that the Dickin Medal is usually awarded to loyal animals like Kuga or the massive and handsome beast known as “Topthorn” in the Speilberg film War Horse. Strangely, however, only five horses have ever received the honour. However, 28 dogs have received the medal, which was discontinued shortly after the Second World War but reinstituted in 2000. The 2000 award was given posthumously to a Newfoundland dog named Gander which saved Canadian soldiers in the Battle of Hong Kong in the Second World War. Thereafter, it was awarded to dogs and horses participating in the Afghan war.

An amazing 32 pigeons were among the 53 animals that received the award for actions taken during the Second World War. The first three recipients were pigeons of the Royal Air Force Pigeon Service, all of who received their medals on the same date—December 2, 1943. The following story concerns a blue checker pigeon hen named Winkie, who, by date of her heroic action, was the first recipient.

February 23, 1942

During the Second World War, the fabled airfield of RAF Sumburgh was a major jumping off point for RAF Coastal Command shipping raiders. Situated on the southern tip of the “mainland” island of the Shetland Island archipelago, it is only about 400 kilometres as the albatross flies due east to the southeast coast of occupied Norway. At 14:29 in the afternoon of Monday, February 23, a detachment of six Bristol Beaufort Mk.II torpedo bombers of Coastal Command's 42 Squadron began lifting off from Sumburgh and shaped a course east for the Norwegian south coast. The six Beauforts of the detachment were led by Squadron Leader W. Hedley Cliff in Beaufort AW-M (RAF Serial No. L9965) who, just the week before, had led a formation the squadron's Beauforts in an attack on the German capital ships Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen during their famous Channel Dash—running the gauntlet of the English Channel from French ports on the Bay of Biscay to find safe haven in the Baltic via the Kiel Canal. Pilots of the squadron reported that they had made successful torpedo hits on one of the ships, but this would later prove to be wrong. The 42 Squadron Beauforts were ordered to conduct a reconnaissance and offensive sweep, seeking to find one or more of the three German warships that might be attempting to join the 52,500-ton monster battleship Tirpitz holed up in Fættenfjord, deep in the labyrinth of the Trondheim Fjord.

A pair of beefy 42 Squadron Bristol Beauforts of Coastal Command thunders over the countryside somewhere in Great Britain. Beauforts of 22 and 42 Squadrons (the first two operational Beaufort units) which were powered by the Bristol Taurus radial engine, were grounded in June of 1940 due to unreliable engines that resulted in the loss of several aircraft under mysterious circumstances. Bulky and not particularly pretty, the Beaufort was designed as a multi-role attack aircraft capable of carrying and delivering bombs, mines and torpedoes. Used effectively by Coastal Command early in the war, the Beaufort continued in service more as a medium day bomber in the Mediterranean and North African theatres. It was taken from front line service not long after Channel Dash, but continued on to the end of the war as a training and conversion platform. The Australians built 700 of them under licence and used them effectively against the Imperial Japanese. One of the Beaufort's greatest claims to fame is that it is the forerunner to the marvelous Bristol Beaufighter, one of the most vaunted anti-shipping aircraft of the Second World War. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Squadron Leader Hedley Cliff's Beaufort AW-M (RAF Serial No. L9965). Illustration by Peter Scott via Wings Pallet—wp.scn.ru

Related Stories

Click on image

The aircraft took off individually between 14:29 and 14:45 and headed east-south-east across the ice-strewn waters of the North Sea for their patrol area between Stavanger and Kristiansand at the mouth of the broad strait in the far south of Norway known as the Skagerrak. The visibility was excellent but they flew through a few scattered snow squalls en route. Needless to say, any operation that required crews to operate over the frigid waters of the North Sea in February was a very dangerous undertaking.

Veteran pilot and flight commander Hedley Cliff took the southernmost and most dangerous patrol area, had the farthest to fly and therefore took off first. Aboard AW-M with Cliff that afternoon were navigator Pilot Officer John Edward McDonald, wireless operator/air gunner Pilot Officer Tessier, and air gunner Sergeant Venn. In his book Shot Down and in the Drink, True stories of RAF and Commonwealth Aircrews Saved from the Sea in WWII, author Air Commodore (Ret'd) Graham Pitchfork identifies the wireless operator as a Sergeant Venn. However, in the 42 Squadron Operations Record Book (ORB) for February 1942, Tessier is entered as the wireless operator for Cliff's crew in an earlier entry. Sadly, the entire Cliff crew is omitted from the ORB on the day they and five other crews set out for Norway. By process of elimination, Venn must have been the air gunner, not the wireless operator. This is confirmed in a photo of the crew taken after this operation, with Sergeant Venn wearing an air gunner's brevet (AG), not a wireless operator's (WOP) or a wireless/air gunner's (WAG).

In addition to the four airmen on board were two homing pigeons carried in separate yellow metal waterproof boxes, stored on a rack inside the fuselage. One of those pigeons was a blue checker hen by the name of Winkie (RAF number NEHU 40 NSL) who had been lent to the RAF via the National Pigeon Service by a pigeon fancier and master plumber named George Ross of Broughty Ferry, Scotland.

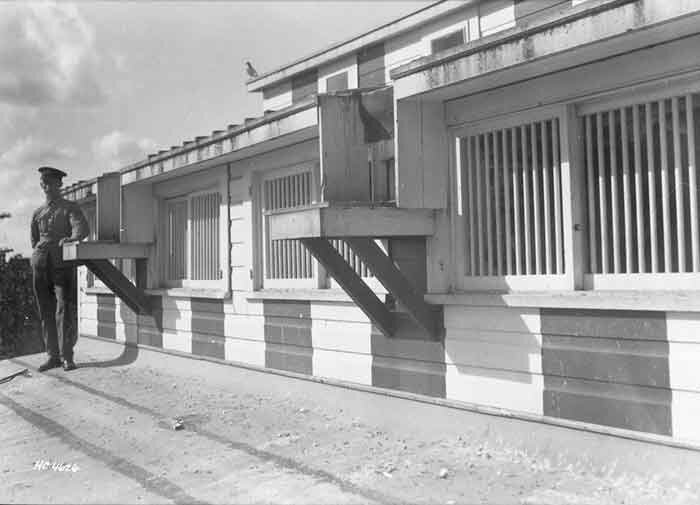

An RAF pigeon fancier loads a bird into a bank of waterproof cages at an RAF Coastal Command base, ready to be drawn by aircrews as they would draw parachutes, rations and sensitive equipment before a mission. Wicker baskets were used early in the war, but later these yellow-painted aluminum box cages were used. The bird could be sealed inside using the lid attached to the left side of the container, giving the pigeon up to an hour and a half's worth of air. Photo: Imperial War Museum

While ground crew (“erks”) do last minute checks on a 42 Squadron Beaufort, others help the four crew members (donning their Mae West jackets) of AW-G for George get ready for a mission. Second from left, an erk places two pigeon carriers next to other equipment. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Two photos showing members of a Coastal Command B-24 Liberator crew loading two waterproof yellow-painted pigeon boxes for pigeons 19A and 19D. In the upper photo, the box on the right has a trough so that the bird can be fed and watered during the long 10-hour plus patrols of many Coastal Command Liberators. The trough had been clipped on 19D's cage as well by the time they were loading them in the bottom photo. These were similar to the type used by 42 Squadron's Beauforts in 1942. Photos: Imperial War Museum

Approaching the occupied Norway, the Beauforts split into six overlapping patrol areas along the coast. Following their sweeps, they were all to land farther south at RAF Leuchars on the coast of Scotland near the mouth of the River Eden. It was a good day for hunting with 30 miles of visibility. Flight Sergeant Manning in Beaufort AW-C reached the coast at 16:10 hrs., spotting two ships (of 3,000 and 5,000 tons) sailing due north at 4 knots, but they turned out to be marked as neutral vessels. Pilot Officer Dawson in Beaufort AW-V landed at Leuchars after four hours without spotting any shipping or enemy activity. Pilot Officer Stoker in Beaufort AW-N landed after 4.5 hours having spotted only a 50-foot Norwegian whaler under sail on a northerly course at eight knots. After circling the ship and seeing no armament, Stoker turned to a course that would take him to Leuchars where he landed in the dark after 19:00 hrs. Pilot Officer Davidson in Beaufort AW-Y flew south but saw only a balloon over land to the east and another Beaufort on a parallel course low over the water. He returned early to Leuchars at 17:10. Pilot Officer Oughton in Beaufort AW-B spotted an aircraft of their port beam, low on the water, but not much else as they prowled the coastline. Oughton touched down at Leuchars at 19:15 hrs. No one had heard from Squadron Leader Cliff in AW-M for some time.

Like every one of the Beauforts that day, the Cliff crew came away from their short recce without spotting any enemy activity. Cliff instructed Flying Officer McDonald to calculate a course for RAF Leuchars, whereupon, at 16:30 hrs, he swung the Beaufort southwest and flew on over the bergy North Sea at 500 ft. About an hour into the flight, with the sun beginning to disappear over the horizon somewhere behind the cloud, a sudden explosion blew apart the port engine. Immediately, the damaged Taurus engine caught fire and the Beaufort began to lose altitude. On seeing the danger, Tessier, the wireless operator immediately tapped out an S.O.S. distress call and then, following procedures, clamped down his Morse key so that a continuous signal would be sent until the aircraft sank and the power shorted out. Seconds later, and only 30 seconds after the explosion, Cliff pulled hard on the yoke flaring the Beaufort a few feet over the water. The heavy aircraft hit the water tail first then slammed down and plowed into the darkening and icy sea. With no time to tighten his harness, Cliff was thrown heavily forward into the control panel, injuring his right shoulder.

As soon as forward momentum stopped, McDonald and Tessier unbuckled, stepped aft and pulled open the large entry and escape hatch on the port side and scrambled out on the wing. What was left of the Bristol Taurus was still smoking and hissing a few feet away. Right at their feet lay the emergency dinghy hatch, which they opened and immediately inflated the yellow rubberized cotton raft by pulling a pin and opening a valve on a CO2 gas inflation cylinder, a process that took no more than 15 seconds. Venn appeared seconds later carrying a basket with the two pigeons and stepped off the wing into the dinghy. He was followed moments later by Squadron Leader Cliff who had struggled to get his parachute off after slamming his shoulder into the control panel and had the farthest to crawl.

Three members of a four-man crew of a Bristol Beaufort climb aboard through the portside access hatch, with the air gunner sitting behind his twin Brownings inside the aircraft's Bristol B.1 Mk V turret. This was the hatch through which the crew of AW-M escaped their sinking aircraft. Photo: Imperial War Museum

As Venn struggled to open the basket so that he could attach a message, the pigeon named Winkie escaped, alighting on the wing just out of their reach. They attempted to entice her back, but she took off and flew away to the west. The Beaufort was now completely awash, so they pushed off and a few minutes later, AW-M slid beneath six foot swells. All four men huddled together as darkness and snow fell. Venn then opened the basket again and carefully extracted the remaining pigeon. Using a scrap of paper, McDonald pencilled in their last known position, rolled it up and placed it inside a small blue aluminum tube (RAF cannisters were blue, Army red) attached to the pigeon's leg. Venn then released the bird, but by now it was dark and the bird refused to fly and landed back on the raft. Pigeon fanciers know that pigeons do not like to fly at night or over large bodies of water. Eventually, after much encouragement, the bird flew off into the darkness and headed west.

That bird would never be seen again.

Assessing their predicament, Cliff understood that the freezing temperatures were their greatest enemy. Though they had only two chocolate bars and several Horlicks malted milk tablets between them, food was not his real worry. They were jammed in a tiny raft in six foot swells on the North Sea at night in February. Food was not an issue as he figured they would die of hypothermia long before hunger. He set up shifts for paddling with the small hand paddles that were contained inside the dinghy—not because he believed they could hand paddle the 150 miles to Scotland, but because he knew the physical activity would warm their bodies and stave off death until the morning when search planes would most certainly be looking for them.

Their faint SOS had in fact been received, but it was so weak that a proper fix on their radial from Leuchars could not be determined with certainty. In the hopes of finding them in the dark, an RAF Catalina flying boat was launched to patrol along the line of Cliff's planned egress from the patrol. Despite searching all night, the Catalina saw no flares. Search aircraft would have to wait until sunlight to begin looking for Cliff and his crew.

At 8:30 AM the next day, pigeon fancier George Ross of Broughty Ferry on the North Shore of the Tay River estuary was checking his loft before work and found an exhausted, oil-stained bird at the back of his loft. After examining her, he recognized her as one of those he had lent to the Royal Air Force at Leuchars, some ten kilometres to the south. He called Leuchars immediately, giving the airman on the phone the serial number on her leg band—NEHU 40 NSL—Winkie, the pigeon that had escaped from the raft. He also told him that the blue message cannister was empty.

The squadron was able to confirm that Winkie was one of the two birds assigned to Cliff's crew the previous day, but because there was no message, they really weren't sure where to look. Since she was covered in oil and because pigeons were known to abhor flying at night, they believed that she may have landed on the one oil tanker that had been in that area of the North Sea the previous night. That, combined with an Army post reporting they too had a weak S.O.S. signal the evening before, convinced them to move their search area farther east. Aircraft were launched later in the morning and at 11:15 hrs, a Lockheed Hudson with a Royal Netherlands Naval Air Service crew from 320 Squadron spotted the crowded dinghy floating on the sea. Circling the tired and hypothermic crew, the Hudson dropped a smoke float and then some basic provisions in what was called a Thornbury Bag—essentially a parachute bag with kapok floats attached, filled with rations, water and cigarettes. A crew member took a photo of the men in the raft during one particularly low pass.

Squadron Leader W. Hedley Cliff and his 42 Squadron Beaufort crew bob in the cold sunlight on the sea as a Lockheed Hudson of 320 Squadron overflies them at 1115 hrs on the morning of February 24, 1942. As well, three of seven 42 Squadron Beauforts involved in the search sighted the dinghy and the circling Hudson and helped to vector a high speed rescue launch to the location of the downed airmen. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The Dutch-crewed Hudson stayed overhead the raft until a Royal Navy Westland Walrus flying boat arrived escorted by a pair of Bristol Beaufort fighter-bombers. The Walrus landed close in to the men in the Dinghy and chatted with Hedley Cliff and his crew. The Walrus informed the four hypothermic men that a Royal Air Force High Speed Launch (HSL) from the Blyth Air Sea Rescue base was well on its way to them. Then, to the crew's dismay, the Walrus fired up its Bristol Pegasus radial and taxied into wind and took off, leaving them once again alone on the water. In the sky, a 42 Squadron Beaufort maintained a vigil. Soon the powerful roar of the 1,500 hp, 64-foot HSL 118 filled the air and to the west they could see Beaufighters and even their own squadron Beauforts flying escort. Soon, over the horizon came the powerful craft, bounding through the swells with spray flying, flags snapping and engines thundering. It must have been a wonderful sight to the crew in the raft. Shortly, the four were aboard with blankets and tots of rum and heading for Blyth, Scotland and the local hospital for treatment.

The 64-foot High Speed Launch (HSL) 118 of the Royal Air Force's Marine Craft Section, ensigns snapping in the slipstream, leaves the Air Sea Rescue Base at Blyth on the East Coast of England headed in the general direction of the suspected ditching. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The 64-foot High Speed Launch (HSL) 118 of the Royal Air Force's Marine Craft Section, ensigns snapping in the slipstream, leaves the Air Sea Rescue Base at Blyth on the East Coast of England headed in the general direction of the suspected ditching. Photo: Imperial War Museum

After getting medical attention, the crew was driven to Leuchars where they were warmly welcomed by squadron mates. The Royal Air Force knew a good story when they saw one and on March 4, Cliff travelled to Edinburgh for a recorded interview with the BBC to tell about his miraculous rescue thanks to a pigeon. While at Leuchars, the crew posed for the press with their saviour Winkie, before heading off for three weeks of sick leave and rest starting on March 10. Four days later, the squadron was informed that Squadron Leader Cliff was being awarded the Distinguished Service Order — though not for his actions in the successful ditching of his aircraft or for his efforts to keep the crew alive through the winter night on the North Sea, but rather for a separate attack on enemy shipping just ten days prior to his ditching.

Not long after their rescue, Squadron Leader Cliff (in sling) gives Winkie the pigeon an affectionate stroke while his crew gather around. According to the squadron Operations Record Book, the crew suffered some cuts and bruises as well as frostbite as a result of sitting in an open raft on the North Sea in February. When the Beaufort torpedo bomber impacted the water, Cliff was thrown forward and injured his shoulder, as evidenced by the sling. Squadron Leader Cliff, DSO sits in foreground while the others are: (L-R) Flying Officer John McDonald, MeD, Sergeant Venn and Pilot Officer Tessier. Photo: Imperial War Museum

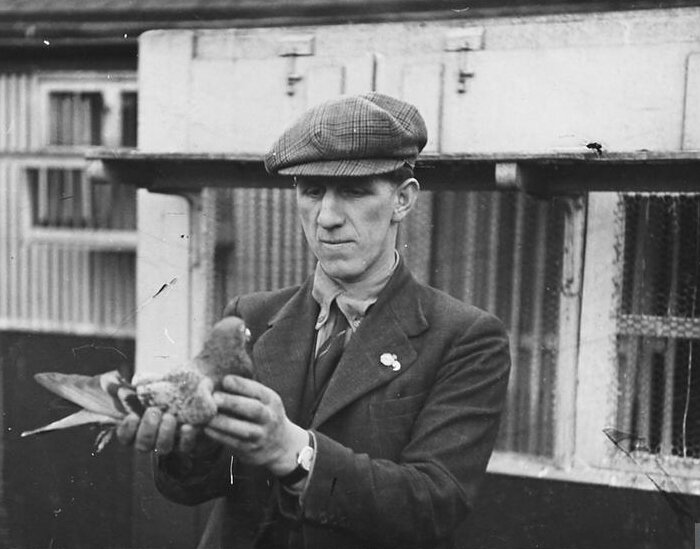

Civilian pigeon fancier and Dundee plumber George Ross displays the super-squab Winkie for an RAF photographer shortly after the story broke in the British newspapers. Photo: Imperial War Museum

After the crew had returned from sick leave, the squadron had a special mess dinner with Winkie as the guest of honour, said to have been “basking in her cage” as she was toasted by the crew and others.

By mid-April, the crew was broken up and its highly experienced members sent to staff or further advanced training postings. Cliff left on April 15 to join RAF Coastal Command Headquarters, while McDonald (who would later be Mentioned in Despatches) was sent off on the 18th for a Bombing Leader's Course at the Empire Air Armament School at RAF Manby in Lincolnshire and Tessier left at the end of the month for a Gunnery Leader's Course at the RAF Central Gunnery School at RAF Sutton Bridge (also in Lincolnshire). Cliff, Venn and Tessier would survive the war, but McDonald, serving as a navigator on a 206 Squadron Liberator, was lost out over the Atlantic on April 8, 1945, just 4 weeks before the end of the war. He was just 23. He has no known grave.

It would take almost two years for Winkie to get her due for the rescue of the four airmen. It wasn't until 1943 that Maria Dickin created the award for animal gallantry and on December 2, 1943 Winkie was one of three pigeons who received the first three awards. The others were a pigeon named White Vision who helped rescue the crew of a 106 Squadron Catalina flying boat forced down in the North Sea off the Hebrides in 1943 and Tyke, an Egyptian-born male pigeon that helped in the rescue of a downed American air crew in the Mediterranean Sea in 1943. Because Winkie's exploits came first, she is often thought of as the first recipient of the Dickin Medal. In February of 1944, Mia Dickin and Wing Commander Lea Raynor, head of the RAF Pigeon Service presented the award to Winkie as well as a special brass plaque from the squadron commemorating her perilous flight.

Mrs Mia Dickin presents the first Dickin Medal to Winkie who is being handled by Wing Commander Lea Raynor, CBE, the founder of the RAF Pigeon Service. Photo: PDSA

Pigeon fancier and RAF Wing Commander Raynor shows us a spread of Winkie's beautiful right wing, while Mia Dickin holds the Dickin Medal the pigeon was awarded. Winkie was a Blue Checker Hen, bred at Whitburn Bents Farm by farmer A. R. Colley and then trained for RAF service by Ross. Breeders and fanciers who joined the National Pigeon Service (NPS) during the war were given a special ration card that enabled them to purchase rare corn and other feed for their pigeons. Note that the background of this photo appears to have been entirely painted over with black ink. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The brass plaque presented by the members of 42 Squadron to Winkie (The inscription reads Pigeon No. 40 N.S.1.) following the awarding of the Dickin Medal. The citation, which is the same that came with Winkie's Dickin reads “For delivering a message under exceptionally difficult conditions and so contributing to the rescue of an aircrew while serving with the RAF in February 1942.” The plaque, designed and made by an armourer of the squadron, was presented at a ceremony at RAF Leuchars. Photo: Imperial War Museum

Winkie would live a full and coddled life for another 11 years and when she died, she was stuffed and presented by George Ross to The McManus Art Gallery and Museum in Dundee, just a few miles from her home loft in Broughty Ferry.

Cliff retired as a Group Captain and, seeking the quiet life, leased a small island in the Channel Island archipelago called Jethou—between Guernsey and Sark and lived there from 1958 until 1964 (the Channel Islands, close to the coast of France, had been occupied by the Germans for most of the Second World War). On Jethou, he researched and wrote a book called Jethou: History, Flora, Fauna and Guide. It was a quiet contemplative life, but in 1962 Cliff would endure another episode with the sea—this time with tragic consequences. He set out for the neighbouring island of Herm in August of that year in a small punt with his 52-year old friend D.H.C. Attenborough, who had been visiting from London. The distance from Jethou harbour to the closest land in Herm was just half a kilometer, but halfway across something happened and the punt overturned throwing both men into the water. The both managed to cling to the overturned punt, but after a while Attenborough lost hold and was drowned. After 10 hours in the cold channel water, Cliff was spotted by a ferry master and rescued. Cliff died in 1969 at the age of just 56.

By the end of 1943, the RAF Pigeon Service, which had not achieved great success save for a few rescues, was withdrawn from Bomber Command and Coastal Command service.