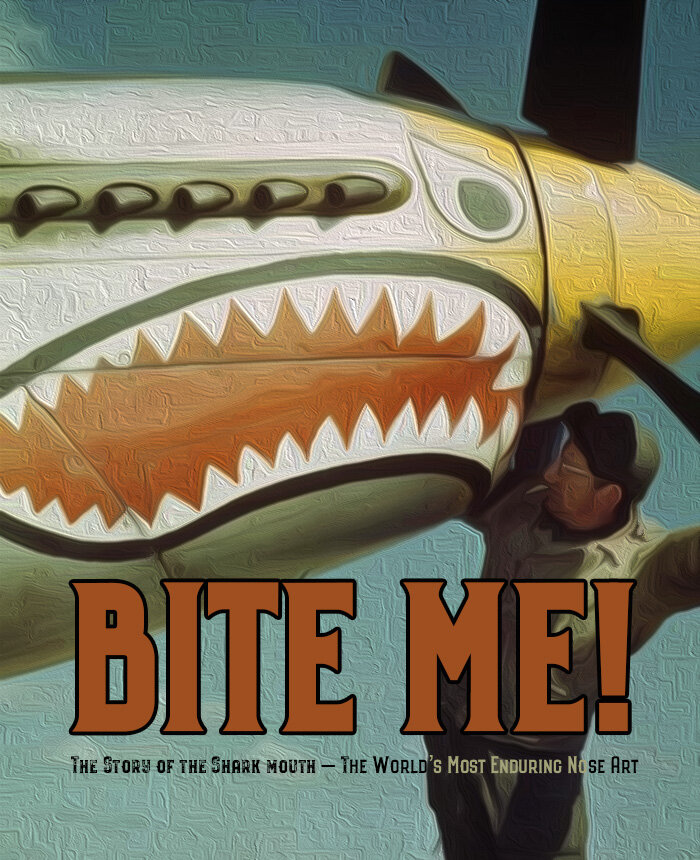

LOWER THAN A SNAKE’S BELLY IN A WAGON RUT

On a particularly hot day, a Royal Australian Air Force English Electric A84 Canberra bomber drops to within 25 feet as thrill-seeking mechanics get ready for the visceral experience of 13,000 lbs of Rolls-Royce Avon power full in the face. Photo: RAAF

Along the sunny Gulf Coast of Mississippi runs a VLA route (very low-level, high-speed flying) frequented by American military fliers for decades. Back in the early nineties, on a dock on Davis Bayou, with a cold St. Pauli Girl beer in my hand, I would sit with my face towards the southern sun and my feet dangling over the receding tidal waters brimming with shrimp and watch as pairs of A-7 Corsairs from the Oklahoma Air National Guard or RF-4Fs from Meridian Mississippi would thunder along the very edge of the horizon following this timeworn route. The “Sluffs” and “Rhinos” came from the Air Guard deployment camp at nearby Gulfport, where they would spend a week practicing being “deployed” at a base far from their home.

These weekend warrior guardsmen as well as regular force fighters would follow the barrier islands from west to east—Chandeleur Island, Ship Island, Cat Island, Horn Island. All uninhabited, all bereft of antennae, chimneys and tall trees. My best friend, Greg Williams, whose dock I was sitting on, was one of those Mississippi Air Guardsmen who had flown this route many times. Living across Biloxi Bay from these islands, he knew them like the back of his hand.

In those early days, he would take a lone Phantom and a back seater, and push himself down low over the Gulf side beaches, ripping from one island to the next heading east from Gulfport. As he came to the eastern end of Horn, the easternmost island, he would bank hard left and run like a scalded dog, low and north, to the wide estuary where the Pascagoula River dumped its brown water into the blue sound.

About a mile inland, Highway 90 crosses over the bayous and the snaking Pascagoula on a slender bridge. A few miles farther north, the four lanes of Interstate I-10 also leap over the two miles of marshland. For years, ass-kicking redneck pilots from Mississippi would approach the Highway 90 bridge from below, climbing to cross the bridge at extreme low level. Complaints from startled citizens in cars and trucks, who had nearly been blown from the road deck, caused the rules to change. All inbound fighters would be required to be at 1,500 feet as they crossed the bridges.

Williams, a long serving and proud recce pilot, and the only Voodoo-qualified, college-educated, shrimp boat captain from Bayou La Batre, Alabama to Boca Chica, Texas, had thousands of hours flying RF-101s and RF-4F Phantoms down where the crawdads live*. Flying low was his passion. His favourite thing to do, when flying in the mountains out west, was to run up the face of a mountain, roll inverted over the top, pull down the other side, roll wings level and toboggan the far side. He was used to it, he loved it, but he admitted once to me that he lived so long on the edge that, from time to time, he toppled over it.

One day in the late eighties, Major Williams and his back seater Major Bernie Cousins streaked at fifty feet down the Gulf side of Horn Island, scattering pelicans and egrets—“lower than a snake’s belly in a wagon rut.” Nearing the island’s slender, curving eastern end, Williams rolled hard left, then level again, heading for the mouth of the Pascagoula. To his right he could see the massive Litton Shipyards; to his left, the small town of Gauthier, Mississippi shimmered in the summer heat. Approaching Pascagoula Bay, he climbed from 50 to 1,500 feet to clear the Highway 90 bridge at the authorized altitude. At 1,500 feet he streaked like an arrow north to I-10.

At the moment the I-10 bridge passed beneath his nose, Williams rolled inverted and snatched the stick back hard to dive for the deck. Flying aggressively for his entire military career, Williams realized immediately that he had pulled too hard and had “buried” the nose of the massive Southern Grey Rhino far past the right line for recovery. It was one of those “oh, shit” moments in a pilot’s flying career when he realizes that he has made a possible fatal mistake.

It was time to employ all his skill and all his physical strength to overcome his error. Instinctively, Williams released the stick, rolled 180 degrees and pulled as hard as he possibly could on the pole. There was nothing else to do but hold on and ride the Phantom out of the mess. Cousins, in the back, having no way to prepare for the manœuvre, blacked out immediately under the massive g-load. Pulling for all he was worth, Williams experienced tunnel vision as he grayed out. He never really saw anything on his periphery, describing the effect of tunnel vision as looking through a toilet paper tube.

At zero feet, the sagging Phantom blew swamp water, mudbugs* and sea grass out from behind as she staggered upward in the humid air and climbed for the heavens. He had overstressed the jet and his own body and very nearly killed himself and his back seater. When I spoke to him about it the other day, he said, “You know, I got complacent and I am not proud of that, it was one time I almost lost it.” It takes a good pilot to admit it, and learn. To this day, Williams says that if you look carefully, you will find two deep parallel grooves in the muddy bottom where he dragged his burner cans though that bayou.

Williams’ story of joy, error, terror and redemption illustrates all that is found in low-level flight in any aircraft—the extreme sensation of speed, a breathtaking sense of your own powerful abilities, the risks of complacency and deadly danger waiting only feet away for the pilot who makes a fatal mistake.

There are two types of flying that are for the skilled and the experienced only—aerobatics and low-level. A show of aerobatics is a beautiful thing indeed, poetry in motion. If aerobatics are ballet, then low-level flying is slam dancing—violent, aggressive and heart stopping. Firewall the throttles of a Phantom and drag a cranked wingtip through the mesquite at the bottom of some gulch in the high Colorado Desert and you have a YouTube video gone viral.

Despite all the risks associated with the practice, it is in fact a safe and critically important skill when practiced by military fliers. The British Ministry of Defence lists some of the key benefits of training their RAF fliers at low level:

Is an essential skill that provides aircrew with one of the best chances of survival

Is a highly demanding skill which can only be maintained through continuous and realistic training

Is conducted with the safety of people on the ground, our aircrew, and other airspace users as the overriding concern

Is rigorously controlled and continuously monitored

Has reduced since 1988—the total number of sorties by a third and those by jets by more than half

Over the past five years I have been sent links to hundreds of low-level flying videos… and only four aerobatic ones… and they were all model airplanes flying in a gymnasium. That tells you a lot about the visceral appeal of the low-level flight. There is no fighter pilot alive in North America who has not used the old saw “I feel the need for speed.” Blowing through Mach 1.5 at 30,000 feet, you are indeed fast. You would only know it…, but never feel it. You want to feel speed? Slow down and get down, way down where the trees rise above you, where men crap their pants when you pass, and the dust and water spray mark your passing.

In the world’s best film ever, Dr. Strangelove, George C. Scott’s character, General Buck Turgidson, when asked if the rogue B-52 can get through the Soviet defences, spreads his arms like wings and proudly expounds in the War Room “If the pilot’s good, see. I mean, if he’s really… sharp, he can barrel that baby in so low… you oughta see it sometime, it’s a sight. A big plane, like a ’52, vroom! There’s jet exhaust, flyin’ chickens in the barnyard!” Right on Buck!

For the past few years, I have dumped any good shots of low-level that I came across on the web into a folder on my hard drive, never knowing what to do with them. Last week, my great friend Ian Coristine sent me an e-mail with a collection of low-level photos someone had put together. Many were already in my folder. So, here finally are the contents of my folder, in tribute to my friends Greg “Hard Deck” Williams, whose aggressive attitude once made him engage a pair of A-10s in ACM (Air Combat Manoeuvring) with his Moonie (and win) and Ian Coristine, who never felt he was flying unless his floats swished in the long grass in a morning sunrise.

* Crayfish, crawfish, crawdads

Ian Coristine inspects the alfalfa in his Quad City Challenger ultralight.

I guess you could say that the first flight in history was in fact a low-level flight. Ever since, men have dreamed for higher altitudes, but did all their showing off right down on the deck.

They loved to fly low in World War Two

A Douglas A-20G Havoc night fighter of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron does a little daylight low flying down in the weeds possibly near the Orlando, Florida base where they were formed. Their first deployment was to Europe where they immediately re-equipped with Bristol Beaufighters.

Related Stories

Click on image

A P-40 flies down the beach at extreme low level, as Marines practice an amphibious landing somewhere in the Pacific. In order to get this photo, the photographer standing on the beach would have had to have his back to the oncoming P-40, trusting that pilot would do a “buzz job” of the beach and not his hair. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

A squadron of Luftwaffe Ju 52 Junkers stream low over the Russian countryside near Demjansk, south of Leningrad. In February to May of 1942, the Germans were surrounded by the Red Army. Supplying the Germans during and after the “Demjansk Pocket” was the role of the air force. Here, low flying in the slow transports was more a survival tactic than a joyride. Photo via Akira Takaguchi

Thought to have been taken in the region of Canterbury, New Zealand in 1944, this shot of an Airspeed Oxford scaring the bejesus out of half the waiting airmen while the other half remain calm, is a beauty. Photo via Joe Hopwood

Two USAAF P-47 Thunderbolts rip down a recently constructed airstrip, while a construction battalion soldier directing traffic holds up a deuce and a half dump truck.

Disregarding the hazards involved, a USAAF 8th Air Force P-47 attacks a Flak tower at a German airfield in occupied France.

A USAAF P-47 Thunderbolt at extreme low level. Note that the sweep of the camera’s pan has bent the buildings in the background.

Another shot that has the same effect of bending the buildings in the background (see previous photo). Like our own Spitfire XIV RM873, Griffon-powered PR Spitfire XIX PS890 was sold to the Royal Thai Air Force after the war. She is seen here with 81 Squadron markings and being put through her paces down low at RAF Seletar, Singapore in the summer of 1954 just before her sale. In 1961, PS890 was donated to the Planes of Fame Museum in California. It was eventually restored and took to the skies again in 2000, albeit with clipped wings and contra-rotating props. It was then purchased by Frenchman Christophe Jacquard and taken to Duxford for the wingtips to be added and a single 5-bladed propeller installed.

It appears that this and the previous photo of a PR Spitfire were taken at the same time and by the same photographer—here an 81 Squadron Photo Recce Mosquito beats up RAF Seletar, Singapore after the war. The navigator stares out the side window at the photographer. Photo: Twitter

A pair (if you include the photo aircraft) of Italian Savoia Marchetti SIAI SM.79s scares the ravioli out of a group of Italian airmen in North Africa in 1942.

Interesting photo. The B-24 in the foreground is possibly the first B-24A. Then there is the group of A-20s doing a low flyby at the Marston Experimental Strip in the Fall of 1941, some 2 months prior to Pearl Harbor. This was the 1st experimental use of PSP (Perforated Steel Planking), also known as Marston Mat. It is being followed by what appears to be Navy Wildcats. PSP played a BIG part in winning the battle for Guadalcanal less than a year after this photo and was subsequently used for quick construction of all-weather runways in remote locations throughout the world. Thanks to Bob Merritt

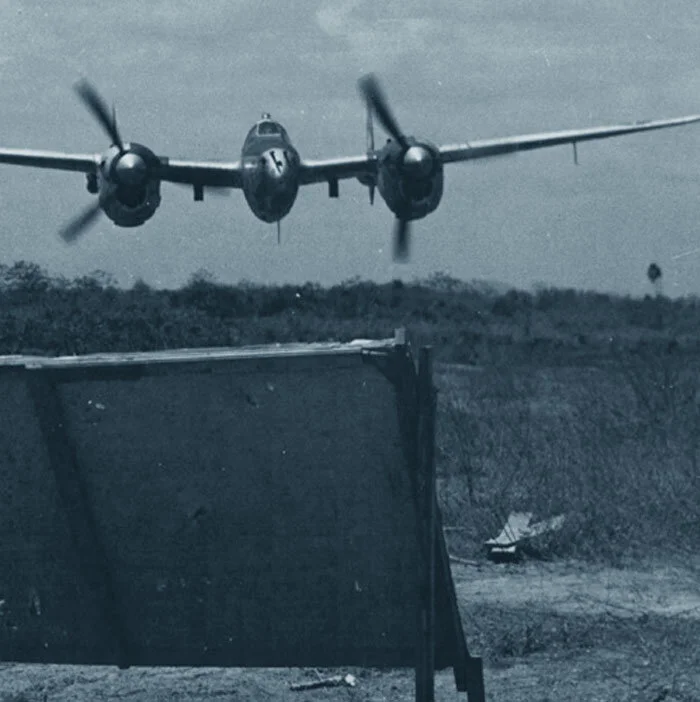

An American P-38 Lightning pilot makes sure of his shot as he lines up a ground target in a Panamanian range during the Second World War.

A P-38 Lightning buzzing the field at Lavenham, England which was the home base of the 487th Bomb Group.

A Photo-Recce Lockheed F-5 Lightning, nicknamed Maxine of the 7th Photographic Reconnaissance group, USAAF beats up a snow covered airfield in Kent. Photo: AmericanAirMuseum.com

An A-20 Havoc beats up sand dunes at Benghazi in 1942.

A Northrop P-61 Black Widow of the 421st Night Fighter Squadron does a low-level pass at Tacloban, Leyte, Philippines in February of 1945.

Westland Whirlwind twin-engines fighters of the RAF buzz a couple of squadron pilots. Photo: Flight Global

A Lockheed Hudson screams in low over assembled photographers and squadron pilots. Photo: Flight Global

A flock of Mitchells head to the target low over the water.

An American Mitchell follows his lead and makes an extremely low-level wave top attack on a sitting duck Japanese picket boat off the coast of Paramushiru in the Kuril Islands. Photo: WarbirdInformationExchange.org

The B-25 Mitchell in the previous photo was attacking its target using the bomb-skipping technique which bounced a bomb off the surface and into the face of the enemy. Here a Beech AT-11 Kansan bomber trainer bounces a bomb right smack into the mouth of the floating target on Lake Childress, Texas. Skip bombing required excellent low flying skills and nerves of steel—some pilots could skip a bomb off a railroad track and into the mouth of a tunnel. Photo: TexasHistory.unt.edu

Blenheim aircraft from 60 Squadron RAF level out for the “run in” to make a masthead attack on a Japanese coaster off Akyab, Burma in 1942.

A squadron of Martin Baltimore light attack bombers in tight formation head to battle.

Showing off your extreme low-level flying skills at an air show or in peacetime takes balls, but flying low-level at chimney top height through oily smoke with Flak and machine gun fire trained on your ass… well that takes big clanging balls. Here, we see a B-24 Liberator named Sandman, among the last through on the raid at the Ploesti, Romania oil refineries, piloted by First Lieutenant Robert Sternfels. A photo taken of his battered bomber, climbing hard to barely clear the smoke stacks of Astra Romania oil refinery after dropping its bombs, would become the trademark photo of the mission so often thereafter associated with the deadly low-level mission against Ploesti.

While researching images for our P-40 stories over the past year I came across a massive collection of marvelous wartime photos—mostly of P-40s collected by Steve Reno. This P-40 pilot is risking his life only a little less than the man taking the photo of this ridiculously low-level pass across the runway. He’s not much higher than he would be if he was standing on his landing gear! If you trace the invisible line of his prop arc, this skilled numbskull’s tips are only about 4 feet off the ground. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

Halifax B Mark II Series 1 (Special), JB911 KN-X, of No. 77 Squadron RAF, making a low-level pass over other aircraft of the squadron at Elvington, Yorkshire. Photo: Imperial War Museum

The same Halifax of 77 Squadron beats up a group of appreciative ground crew at RAF Elvington in Yorkshire in 1943. The pilot of this aircraft couldn’t have much more than a few hundred hours, but clearly a lot of testosterone.

For many attacking aircraft, safety lay down low in the wave tops beneath enemy radar coverage. Here, a squadron of Douglas A-20 Boston bombers of the RAF’s 88 Squadron head to the target over the North Sea. 88 Squadron crews became highly proficient in low-level bombing.

In December 1942, almost 100 aircraft from 2 Group attacked the Philips Valve Factory at Eindhoven including 12 Bostons from 88 Squadron at RAF Swanton Morley. They were led by W/C Pelly-Fry, the CO of 88 Sqn. Pelly-Fry’s aircraft was hit just after he had released his bombs. With much-reduced hydraulic pressure, a large hole in the starboard wing and a coughing and spluttering starboard engine, he narrowly avoided the rooftops but found that the aircraft could not climb above 800 ft, nor could he keep up with the others on the way home. Despite his difficulties, he fought off two Fw 190s before eventually managing a belly-landing back at Oulton. Deservedly, he was awarded a DSO; the raid also resulted in the award amongst the other crews of another DSO, two DFMs and eight DFCs.

But not all the low-flying was “in the face of the enemy.” A former 226 Squadron flight commander, a navigator, relayed to me one such series of antics by which his crew “nearly came a cropper.” The pilot and captain of his Boston was Sqn Ldr Shaw Kennedy (who became, after the war, the Air Attaché in Prague.) Kennedy was a brash Irishman with a wild and wicked sense of humour. His favourite jolly jape was to buzz the German and Italian prisoners of war working the fields around the perimeter of Swanton Morley airfield.

At this point in the story, it helps to understand that Swanton Morley airfield is situated on the top of the only significant hill in central Norfolk. Despite being a mere 150 ft or so above sea level, the ground falls away significantly on the north and eastern edges of the airfield into the valley of the River Wensum. Kennedy’s “standard approach” was from the east, hugging the bottom of the river valley before banking sharply to port and roaring up the slope at full power over the startled POWs, who immediately hit the dirt to avoid getting a haircut.

Kennedy would then stay low, heading south across the grass airfield, before banking steeply to port again across a small pond, surrounded by trees, to the south of the hangars. He would shave the tops of the trees which, to this day, are shorter in the middle than at the outside, due to his “pruning.” This unorthodox procedure worked fine until one, almost fateful, day. As Kennedy rolled out of the left bank to scare the POWs again, his navigator (sitting in the nose) noticed that the POWs had all ducked down well before the Boston would be on them. Sensing that the POWs were up to something, he had no time to tell Kennedy to pull up as all the POWs threw their farming tools in the air as high as they could - straight into the path of the Boston. There were fleeting visions of rakes and spades flashing over the wings and the faint ping of something ricocheting off a prop. Fortunately, Kennedy managed to land the Boston safely. He never buzzed the POWs again! (Story from Squadron Leader Alan R. James (Ret’d)

A powerful photograph of a USAAF B-25 Mitchell bomber attacking shipping in the South Pacific. Judging by the tracks of gunfire, there are other aircraft on other heading firing at the obscured target. The high mountains and confined area make this low-level attack particularly dangerous. There appears to be a trail of bullet splashes either following or coming from this Mitchell.

Two of twelve U.S. A-20 Havoc light bombers on a mission against Kokas, Indonesia in July of 1943. The lower bomber was hit by anti-aircraft fire after dropping its bombs, and plunged into the sea, killing both crew members.

Sometimes, flying low is not your choice. With its gunner visible in the back cockpit, this Japanese Nakajima “Kate” dive bomber, smoke streaming from the cowling, is headed for destruction in the water below after being shot down near Truk, Japanese stronghold in the Carolines, by a Navy PB4Y on 2 July 1944. Lieutenant Commander William Janeshek, pilot of the American plane, said the gunner acted as though he was about to bail out and then suddenly sat down and was still in the plane when it hit the water and exploded.

Three Japanese Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers with torpedoes aboard scream extremely low into the target at Guadalcanal. At this height, the bombers are well set up for a launch of their “fish” and at the same time, as witnessed by the explosions above them, somewhat safe from AA fire.

Dornier Do 17 light bombers approach England at Beachy Head during the Second World War.

A dangerous game. In the top photo we can see a Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk of the Royal New Zealand Air Force with a good lead in a race against a Lockheed PV-1 Ventura at RNZAF Station Ohakea near the city of Bulls, North Island. The lower photo shows the Ventura as it passes the photographer. The occasion was a race between aircraft of two operational training units (OTUs)—the Kittyhawk from No. 4 OTU and the Ventura from No. 1 OTU. Photos: RNZAF.proboards.com

I’m not sure if this is real or faked, as the Heinkel He 111 aircraft seem almost too close together as they fly low over the English Channel bound for England in 1940.

A Vickers Wellington I medium bomber is about to scare the bejesus out of this RAF photographer at RAF Bassingbourn, in 1940

An RAF Blenheim IV light bomber flies low to lay a smokescreen during a demonstration of air power in front of a gathering of Regular and Home Guard officers and NCOs in East Anglia, 29 March 1942. During the display fighter aircraft strafed ground targets, bombers carried out low-level attacks and parachute and glider forces were also deployed. Photo: Imperial War Museum

A six-pack of USAAF B-25 Mitchells chase their shadows across the North African desert. The web is filled with shots of Mitchells down low… something they and their crews were particularly good at.

Lower than a snake's belly in a wagon rut. Another of my favourite photographs of the Imperial War Museum's collection depicts a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombing a bridge at extreme low level. We don't see the Liberator, but its shadow tells us just how low it is, and if one looks very cafefully, a stick of bombs can be seen dropping just off the port side of the shandow's nose. The wooden road bridge was between the the cities of Pegu (now known as Bago) and Martaban in Burma.

This is the only shot in this story without an airplane in it or even a shadow of one. It was taken by an American aicraft whilst strafing a Japanese destroyer. This is possibly a shot taken during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, when American Havocs attacked Japanese transports and destroyers. It shows just how low these pilots were willing to fly. Photo: jalopyjournal.com

A very famous shot of a P-47 pilot flying though the trouble he has wrought when he hit an ammunition truck.

There is often a price to pay

‘One more beat-up, me lads.’ Flying Officer Cobber Kain, DFC, a New Zealander and the RAF’s first ace of the Second World War makes a fatal mistake. On the 6th of June 1940, Kain was informed he would be returning to England the next day. The following morning, a group of his squadron mates gathered at the airfield at Échemines, France to bid him farewell as he took off in his Hurricane to fly to Le Mans to collect his kit. Unexpectedly, Kain began a “beat-up” of the airfield, performing a series of low-level aerobatics in Hurricane I L1826. Commencing a series of “flick” rolls, on his third roll, the ace misjudged his altitude and hit the ground heavily in a level attitude. Kain died when he was pitched out of the cockpit, striking the ground 27 m in front of the exploding Hurricane. Kain is buried in Choloy War Cemetery.

Some aircraft, such as this Spitfire, reach that fine line between crashing and flying low… about 12 inches too low in the case of this 64 Squadron Spitfire with shattered wooden blades. The aircraft, no doubt shaking badly, was nursed back to the safety of an Allied base.

An Allied pilot, flying a Macchi 200, buzzing Taranto, Italy. It sadly proved that these kind of stunts aren’t without danger as the pilot hit a member of the ground crew and more or less decapitated him. The pilot hadn’t noticed a thing and after landing was confronted with a dent in his wing’s leading edge, containing skull fragments.

Perhaps the best and scariest seat from which to enjoy some low-level flying is from the bombardier’s seat in the nose of a bomber… in this case a Luftwaffe Heinkel 111. Photo via Thomas Harnish

A P-47 of the 64th Fighter Squadron, while on a mission to Milan, struck the ground during a low-level strafing run. Despite the bent props and crushed chin, the pilot nursed the Jug 150 miles home to Grosseto. Photo via Hebb Russell

A P-47 flown by Lt. Richard Sulzbach of the 364th Fighter Squadron, 350th Fighter Group, 12th Air Force on 1 April 1945. Lt. Sulzbach had a little run-in with some trees while on a strafing run over Italy. He was able to fly the plane 120 miles back to base and land safely. It’s a real testament to how tough the P-47 was.

A Fairey Gannet at extreme low level, trailing smoke.

The Strange Case of Donald Scratch

Not an extreme low-level shot, but this image of a P-40 chasing a B-25 Mitchell over buildings in the Vancouver area is worth a lengthy explanation. Jerry Vernon explains:

“Sgt. Scratch was born in Saskatchewan, 7 July 1919, and enlisted in the RCAF in Edmonton, as R60973 AC2 on 20 July 1940. He earned his wings as a Sergeant Pilot and flew with that rank for a long time. He flew Liberators from Gander, Newfoundland, as a co-pilot on anti-submarine patrols. Scratch was good at his job and was eventually raised to commissioned rank. On two separate occasions, Scratch stole multi-engine bombers and engaged in lengthy low-level and dangerous flying.” Jerry Vernon explains:

“Scratch had injured his leg in a previous Bolingbroke accident, and the powers-that-be felt he did not have enough strength in the leg to control the rudders on a Liberator if he lost an engine. For that reason, both at Gander and at Boundary Bay, they would not give him a captain’s qualification, which is what pissed him off.

On the first occasion, they were concerned that he was going to fly the aircraft down to New York City, but he thought better of it, and returned to base. He later told classmates at Boundary Bay that had been his intention. He had taken a Liberator without authority at 0345 hrs on 20 Jul 44, and “for 3 hours and 10 minutes engaged in an exhibition of dangerous low flying over the aerodrome and vicinity.” He told the Court of Inquiry that, after 3 years of operational flying on the East Coast, he was determined to participate in another theatre of war.

I suppose that qualified pilots were in such demand that they allowed him to re-enlist as a Sgt. Pilot less than 3 weeks after being dismissed by General Court Martial. Former CPAir PR head Jim McKeachie, a member of the Quarter Century in Aviation Club and 801 Wing, Air Force Assn. of Canada, was on the same course as Don Scratch at Boundary Bay, and had dinner with him in the mess that night before the event here. McKeachie then went off on a leave pass and was not on base the next morning when the Mitchell escapade took place… however, Jim does have his own version of the story, which I have heard from him several times!!

Scratch began a 6-week course at No. 5 OTU as a Mitchell 2nd Pilot and was due to graduate on 11 Dec 44. His Flight Commander regarded him highly and stated in evidence that “He was a very keen, average pilot. He was neat in his appearance and had a pleasant personality. He was very quiet and generally well-liked.”

Apparently Scratch wasn’t normally a heavy drinker, but got drunk that night before attempting to steal a Liberator and then stealing the Mitchell. Others in his barrackroom stated that they had never seen him drunk… but the Bar Steward testified that he had sold him between 12 and 18 bottles of beer that night!! He attempted to persuade a WD to come with him, but she wisely refused. There is no mention in the file of the Liberator hitting a bridge… the file says it was bogged down in the mud, and a 2/3 full mickey of Jamaica Rum was found dropped down between the pilot seats, with Scratch’s fingerprint on it.

The Court of Inquiry notes that he had been drinking beer in the Mess and did not occupy his quarters that night. At 0200, he visited the Stn. Signal Section and offered a drink to the WD on duty.

He did not fly down to Seattle, but the RCAF were afraid that he would, and the P-40s had instructions to shoot him down if he crossed the border, which he did not do. Otherwise, if he stayed inside Canada, they were to stick with him and try to force him to land. He did not fly down Granville St. downtown below the level of the building… as far as I am concerned, it would be physically impossible to do with a Mitchell!! However, per statements from the CO, it sounds like he did fly over parts of the city.

He did fly around and “visit” several of the RCAF stations in the area, possibly Pat Bay and I think Abbotsford for sure… the Court of Inquiry file only mentions Abbotsford and an extensive beat-up of Boundary Bay. In fact, as a kid during WW II, I lived on 176th St., several miles due West of the Abbotsford Airport, and one morning a Mitchell came over our farmhouse at chimney-top level, and I have suspected it may have been Scratch. However, the date seems to rule it out, unless I was back visiting with my grandparents at the time. I moved into Vancouver in the summer of 1944 and I don’t know when my grandfather sold the farm, as he was living over near Cloverdale by the summer of 1945, as I recall being there when VJ-Day occurred.

I have seen a photo of him buzzing the CO’s morning parade at Boundary Bay, well below tower and hangar height. It is in the C of I file in Ottawa, which as I recall also contains some newspaper clippings.

The C of I file says that he beat up Boundary Bay from about 0600 to 0700, then headed for Abbotsford. He then returned and beat up the buildings, runways and parked aircraft at Boundary Bay, incredibly missing some objects by inches. At one point, he flew the entire length of the tarmac between the line of parked aircraft and the hangar, with his props inches off the ground. He could be seen in the cockpit without headphones on, so he could not hear tower transmissions to him… the CO had gone to the tower at 0630 and taken personal charge of the situation.

The Court of Inquiry decided that, even if he had been drunk when he started out, after several hours of flying and strenuously throwing the aircraft around, he was probably cold sober by the time he crashed.

The C of I ruled that it was not a suicide, as some thought it was. He had flown the aircraft for several hours, up to the point that the fuel should have been exhausted. Mitchell HD343 had taken off at approximately 0454 hrs from the unlit runway and flew around for 5 hrs and 15 minutes until crashing at 1010 hrs, after about 5 hrs and 15–20 minutes flying. The Court felt that, as he pulled the aircraft up sharply, one of the engines was starved of fuel and cut out or faltered, thus causing a wingover and the aircraft dove vertically into Tilbury Island, not far from the present Deas Island highway tunnel and the Deas Island Park. I wonder if there is still any trace of the large water-filled crater that is shown in photos?

It had been calculated that the aircraft would run out of fuel about 0930, but it did not crash until 1010 hrs, so that lends some credence to the theory about it running out of fuel.

The Court had considered several possibilities…

A: Pure accident, ie: loss of control at high-speed. No.

B: Failure of fuel supply to lower engine when wings of aircraft were vertical in last pull-up. With one engine running and the other cutting out, the aircraft would have done a wingover and dived towards the ground. The aircraft was at high-speed and flying at 800–1,000 ft. at the time and the Court felt it would have been impossible to pull out. This was the accepted findings of the Court.

C: Loss of control due to physical exhaustion… no sleep that night, heavy drinking, 5 hours of violent aerobatic manœuvres, etc. could have resulted in a physical collapse. No.

D: Suicide. No evidence that he was suicidal, so “No” again.

Insanity. No. He had been examined by RCAF shrinks and the Court had no alternative but to find him sane.

However, the remarks of the CO suggested that Scratch must have been suffering from some sort of mental depression or an inferiority complex. He felt that the flying was so dangerous that no-one in a balanced state of mind would fly that way for such a long period. The CO and several experienced pilots felt that a pilot in a balanced state of mind would have frightened himself so badly that he would have quickly stopped flying this way.

No. 5 OTU operated out of both Boundary Bay and Abbotsford. In general, Mitchells were used at Boundary Bay and Liberators at Abbotsford, and the basic 4 or 5 man crew trained first on the Mitchells and then were joined by the Air Gunners at Abbotsford on Liberators for further work-up. There wouldn’t normally have been many (or any) Liberators at Boundary Bay, but there apparently was at least one there that day. 5 OTU used the Boundary Bay-based Kittyhawks for “Fighter Affiliation Training” for the Liberator Air Gunners, so perhaps that is why one would have been at Boundary Bay.”

Filmmakers love low-level flying!

Not actually a scene from the Second World War, but rather the opening scene in the great film A Bridge Too Far. A school boy watches over his shoulder as a recce Spitfire rips up a cobbled road in the Netherlands.

Modern day photographer Murray Mitchell captured this action shot super low B-17 Flying Fortress performing for a film crew and followed by a P-51D Mustang and a P-47 Thunderbolt. Photo via www.murraymitchell.com

A low flypast during the filming of the Steve McQueen–Richard Wagner film, The War Lover. Nothing like a good buzz job to get the juices flowing; in this case one of the War Lover ex PB-1Ws being flown by John Crewdson for a key scene in the movie. Crewdson reportedly flew the airplane solo for the sequence. For some outtakes from this day of filming, visit YouTube. Photo by David M. Kay

A Royal New Zealand Air Force Canberra presses vapour from the air on a low flyby in 1970 before being sold to India.

Not to be outdone by the Canberra boys, this Royal New Zealand Air Force A-4K Skyhawk from 2 Squadron executes a picture perfect low-level top side pass. Photo: RAN RNZAF Skyhawk page on Facebook

Sometimes, the difference between ground and aircraft is quite literally… inches. A Piper Cub comes as close as possible to a wing strike without damage.

A Royal New Zealand Air Force Harvard makes a low-level turn and drags a wing tip.

The Piha Surf Life Saving Club near Auckland, New Zealand is one of the country’s most famous and has been in existence since 1934. The daring young people who form its membership would be the very same kind who would go to war in the air six years later. Before being posted overseas during the Second World War, Piha Surf Club member Ernie Laurie used to fly from Hobsonville to strafe Piha. Photo via x-planes

To give you a sense of the beautiful geography of the Piha Surf Life Saving Club (previous photo) in which Ernie Laurie flew his Harvard, here is a photo from the club showing the same promontory today.

Geoffrey Tyson repeated the feat of picking up a handkerchief with a spike on the wingtip of his Tiger Moth more than 800 times while flying with National Aviation Day Displays, 1934–36 in Great Britain.

Another great shot of a Belgian Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar executing a super low-level flight at Deurne Airfield… with just one engine! You get the feeling that the loadmaster could just step out that rear crew door onto the field. Photo via www.belgianwings.be

Two Turnin’ and Two Burnin’ goes the old adage about the magnificent Lockheed Neptune, referring to the two radial engines paired with two turbojets on wing pylons. Here a Dutch Lockheed SP-2H Neptune (7248) Koninklijke Marine 320 Squadron does a “spirited, low-level” pass at a Prestwick Air Show in 1981. Photo: Gordon Macadie

The legendary Don Bullock was well known for his low-level flying… in particular in B-17s. Here, he beats up the field at Biggin Hill.

Also at Biggin Hill, Don Bullock coming “out” of the valley at the 1979 Biggin Hill Air Fair. Bullock would eventually kill himself and six others in a B-26 Invader in this very spot after a botched manœuvre at low altitude.

Sun-baked boredom causes low-levelitis

A particularly heartstopping photo of a Hawker Hunter of the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force beating up the base at Thumrait. The Sultan employed former RAF pilots to fly Hunters and Strikemasters to help put down the Dhofar rebels in the south. They clearly were bored from time to time! The rebellion ended in 1976, the same year I visited Oman. One of our readers, Kevin Turner, writes: “I used to work at Thumrait back in the 1980’s and 90’s and this was standard practice when returning from a sortie in those bad old days, most of the pilots were seconded from the RAF or contract pilots. I think the Jaguar was being flown by Dick Manning, an ex-Phantom jockey from the RAF and a regular low-level “offender.” He used to aim for anyone walking out on the pan! You could hear the Hunter coming as it had this low frequency howl before it arrived, but the Jag was totally silent until it arrived and your senses were shattered by the noise! We even had a Jag hit a car being driven by one of the Hunter pilots coming back from Salalah. That was Dick Manning again. The centreline pylon caved the roof in and the ventral strakes on the engine doors took the A, B and C pillars out on the car. Dick said he didn’t even know he’d hit the car!!! Another Jag hit the Range Safety Officers walkway handrail with the outer section of the port wing during a beat-up. Other versions of this type of flying in Oman are on YouTube I think.”

A Hawker Hunter pilot of the Sultan of Oman’s Air Force (SOAF) shrieks across the ramp on an Omani air base. Photo via PatricksAviation.com

In the shimmering white heat of an Omani summer day, a Sepecat Jaguar adds superheated jet exhaust to the miserable mix as its pilot shows off for the ground personnel watching from the shade. In 1990, the SOAF was renamed the Royal Air Force of Oman (RAFO). Since this photo was taken in January of 1981, this would be an SOAF Jag. The shot was taken by Bill Fletcher, a British contractor working on maintaining the Jaguars and Hunters at Thumrait. What is not clear in the photo is that behind the photographer a fuel bowser was crossing the ramp and the Jag had to do some drastic manœuvring to avoid disaster. Tim Croton, the son-in-law of the photographer, tells us the aircraft was at 10 feet of the deck—plus or minus two feet!

Two Armée de l’Air Sepecat Jaguars about to scare the bejesus out of a beach walker on a West African shore during Opération LAMANTIN, the French military campaign in support of the Mauritanian government in 1977 and 1978. The Mauritanians were fighting a group known as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el-Hamra and Rio de Oro (Polisario Front for short), who were fighting for independence for the former Spanish colony known as Western Sahara from the French in Mauritania and Morocco (who took control after the Spaniards had left). Photo via TheAviationist

Two RAF Sepecat Jaguars fly extremely low over an Iraqi Air Force hardened bunker and a MiG-23 on the ramp while an Iraqi soldier watches… likely crapping his pants. It is not known if this image is from the Gulf War or before since it is hard to imagine that an RAF Jaguar would leave the MiG unmolested in the Gulf War. The distance of the shadow from an aircraft tells us just how low the pilot is. In a millisecond that shadow will get closer still as it climbs up over the roof of the hangar.

An Argentinean Pucara ground attack aircraft forces mechanics to hit the tarmac in this dramatic low flyby.

But forest, buildings and mountains make it more exciting

A Dutch F-16 with burner lit seems to follow the turn in the road. On the ground, Dutch airmen stuff fingers in their ears as he passes overhead.

Testosterone fired, speed addicted, and happy-to-still-be-alive youth were the primary source of pilots of the Second World War. At 6 foot, 4 inches, I wouldn’t want to be standing up on the runway for this beat-up by a Mosquito. This aircraft had the military serial number RR299 and was built as an unarmed, dual control trainer at Leavesden in 1945. It served in the Middle East until 1949, when it returned to the United Kingdom. It then served with a variety of RAF units, this service being interspersed with periods in storage. The aircraft was retired from the RAF in 1963 and was acquired by Hawker Siddeley Aviation (now British Aerospace) at Chester. The first Permit to Fly was issued on 9 September 1963. The aircraft continued to be based and maintained at Chester and typically flew around 50 hours per year. The Mosquito crashed in 1996 with the loss of the crew. Photo C F E Smedley/Oscarpix Imaging

Saab test pilot Ove Dahlen flies a mini-counter-insurgency aircraft variant of a trainer, known as the Malmo MFI-9B, between houses in Sweden. The concept of a super-light, super-cheap attack aircraft with hard points for rockets was not well received and SE-EFM was eventually sold (as all other MFI-9B trainers were) as a civilian sport/general aviation aircraft; but for a while it was a bad-ass attack aircraft clearly capable of sneaking around buildings. Though SE-EFM and the purpose-built mini-COIN concept did not take hold, 5 airframes of the MFI-9B trainer, known as the Biafra Baby, were fitted with rockets and employed in the conflict in Biafra.

The “Gutless Cutlass” looks pretty capable in this shot of a Vought XF7U-1 “Cutlass” prototype being photographed by the press on 18 November 1948 at the Naval Air Test Center at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland (USA).

Bombers do it

This is my favourite of all the low-level shots, as the people (except the man on the left who is smartly covering his ears) have no idea how low this Avro Vulcan really is as it sneaks up behind them. Though this was a formal and serious occasion at RAF Swinderby (a graduation ceremony), there were no doubt some shrieks and some Olympic flinching when the sound reached them.

Second runner-up in the Imminent Coronary Category is this Fleet Air Arm de Havilland Vixen a mere 30 feet overhead a Forward Air Control team at Naval Air Station Yeovilton. Photo: Royal Naval Reserve Air Branch

Another pair of Forward Air Controllers appear to be looking in the wrong direction as this F-4K Phantom II is a half second from blowing them clean off the Land Rover. Photo: Royal Naval Reserve Air Branch

A British-based B-17 flown by Don Bullock beats up a grass field.

The Canadian Warplane Heritage Lancaster drops down to the infield of the Saskatoon airport.

Royal New Zealand Air Force Short Sunderland doing a touch and go at Wellington airport in 1959—Surely no-one can go lower than that! A touch and go in a wheelless flying boat is not recommended. You couldn’t get a damn slice of pastrami between the hull and the runway. There exists a crystal-clear shot in one of the RNZAF flight-safety publications that showed the aircraft just after it had done the “touch and go” clearly showing the bilge water escaping. Spectators were treated to a shower of dirty bilge water as it climbed away.

Another Sunderland being “demonstrated” at Port Elizabeth, South Africa, may not be as low, but the pilot gets full degree of difficulty points for having two props feathered!

Thought two feathered engines on the same side was impressive for low-level flight? How about three feathered and 20 feet below? This Avro Lancaster appears to be postwar with the nose turret de-activated and a dome in the dorsal position. This is a very foolish manœuvre.The aircraft can’t be flown on a single engine. It’s done by a dive, a high-speed pass and a zoom climb at the far end of the runway with a mad scramble to unfeather. The situation gets serious if the first unfeathering knocks the generator on the good engine off-line, leaving only battery power. Photo via Blake Reid

An Avro Lincoln executes an extreme low-level pass with only one of its four Merlin engines turning. It’s hard to distinguish the Lincoln from the Lancaster at this angle, but the facetted glazed nose of a Lincoln can just be seen below the nose turret. To do this pass, the Lincoln’s pilot must have dived on the field to give him the speed he needed to climb out and restart.

There were three squadrons in the RAF with an LK squadron code, but only two of them flew the Halifax—51 and 578 Squadrons. Of these two, 578 Squadron had one particular Halifax that flew more ops than any other—LK-W (MZ527). Given the number of bombing mission numbers on the nose of this Halifax, it was my guess that we are looking at the 578 Squadron LK-W as she celebrates some milestone. A quick look on Wikipedia brought confirmation that this was the 578 Halifax, beating off the RAF Burn control tower, F/L “Maxie” Baer at the controls. Baer was a native of Toronto, Canada and was celebrating the completion of his tour. Photo: RAF

Rhinos LOVE to do it

An RAF Phantom II in full burner passes between two hangars at RAF St Athan in South Wales. There isn’t a Rhino-driver alive who didn’t love dropping his locomotive-sized Phantom down to the hard deck and pushing the throttles right past the detents. Darryl Dyke, a former airman at St Athan, writes: “I used to work at St Athan and the incident was legendary there. There was also a story that the pilot, a Wing Commander, had something of an argument with the base commander following the incident after which the pilot, on his next flight, flew low over the base headquarters, pulled the nose to vertical and pushed the throttles to afterburner. A pair of Speys with the taps open don’t half make a mess of conference room glass roof!”

Like I said before, Phantom drivers love it down low.

Flying even lower than the Greek economy is this GAF F-4 Phantom II picking its way through the bushes.

Down low, add in a little rock and some flat water and the fun escalates. This picture was taken in Goose Bay, Labrador and the aircraft is from the Luftwaffe’s FBW 35, where Oberst Dieter Reiners was commander of the flying group at the time. Oberst Reiners tell us, “We used one set of aircraft the whole season and the different wings would paint their crest on the aircraft, when they took over. The crest from Flugplatz Pferdsfeld was blue and yellow and my maintainers had forgotten to bring blue paint, so I ordered to use red paint!! And that is what you see. It could have been me, flying that aircraft over Harpers Lake, but I cannot tell the tail number. It was legal, by the way, to fly that low!!”

A Panavia Tornado spews heat, gas, and vapour as she howls from the runway with her wingtip a few feet off the ground.

From Colin Smedley comes this magnificent image that seems to show 55,000 pounds+ of Blackburn Buccaneer hovering over the runway. In the 1980s and 90s, No. 208 Sqn RAF were the real experts in ultra low-level under the radar nuclear strikes. During the International Air Tattoo in 1993, to mark the squadron’s 75th birthday, this Buccaneer S.2B was flown at an altitude of just 5 feet for the entire length of RAF Fairford’s runway. From inside the massive strike aircraft, it must surely have felt as though they were actually in the ground. Thank God for ground effect. Photo: Colin Smedley

On 13th June 1992, flamboyant Russian test-pilot Anatoly Kvotchur in his Sukhoi Su-27P “Flanker” arrived at the Air Tattoo International at RAF Boscombe Down in company with his T-134A “Crusty” support aircraft. He maintained formation as the Tupolev completed the let down and landed and stayed in position until the transport engaged reverse thrust. At this point many observers were certain that his Flanker was actually lower than the larger aircraft which had all its wheels on terra firma! He kept the Flanker low and in a hi-alpha attitude for most of the runway before regaining circuit height by the simple expedient of opening the throttles. Photo: Colin Smedley

During an air show at RAF Wethersfield in 1964, Belgian Air Force pilot Jo Marette in a Republic Aviation F-84-F Thunderstreak flies not only feet off the ground, but apparently just feet from the crowd. Times have changed. While perhaps not as exciting for the spectators, it is certainly safer.

Warbird display pilot John Allison brings in Lindsey Walton’s F4U-7 Corsair low and fast over the boundary hedge at the Fighter Meet at North Weald in 1985. Photo: Colin Smedley

Not really low-level flight, this pilot nearly buys the farm at the bottom of a loop. The tail strike occurred during a 1990 air show in Harrison, Arkansas. The photographer, who was a technician for the FAA and somewhat of a camera buff, was tracking with his camera, as this guy looped off the deck in a MiG-17. The pilot had just completed a loop and misjudged his pull-out. Everyone considering themselves as potential victims took off running in all directions. But the photographer had a non-threatening position along with a strong motivation to take the picture. So, just as the MiG scraped the ground, he captured this rare image… Oh, by the way, the guy just made a wide circle, lowered his landing gear, touched down and then taxied in showing scratched paint, but no sheet metal damage. Photo: Kelly Angell

The legendary Ormond Haydon-Baillie checks our wheat production at a farm outside of Duxford in 1974 in his T-33 (RCAF 21261), the Black Knight. Born in Devon, England during the Second World War, OHB moved to Canada in 1962, joining the RCAF. He would become a well-known warbird collector and pilot after his service.

Another crazy low pass by Ormond Haydon-Baillie in his Black Knight T-33 Silver Star. The spectacular paint scheme is based on an RCAF design for 414 Black Knight Squadron that flew the type. Vintage Wings of Canada is proud to have been part of 414’s history. The squadron was disbanded in the 1990s. However, in December of 2007, approval was received for the squadron to stand up once more, this time as 414 EWS (Electronic Warfare Support) Squadron. Belonging to 3 Wing Bagotville, the squadron is based in Ottawa and is composed of military Electronic Warfare Officers who fulfill the combat support role, flying on civilian contracted aircraft. The squadron was re-formed at the Vintage Wings hangar at the Gatineau Airport on 20 January 2009 to operate the Dassault/Dornier Alpha Jet provided by Top Aces Consulting. Haydon-Baillie died in Germany in a P-51 Mustang on 3 July 1977.

A fine shot of an RCAF Golden Hawk Sabre burning the concrete ramp.

With speed brakes out this is neither a landing nor a takeoff. This low flying Lightning is an F6 in 5 Sqn markings. The photo is definitely of a low pass since wheels-up landings were not to be attempted in a Lightning due to the large ventral tank underneath. In the event of the ‘cart’ not coming down, the standard Lightning action was to point the aircraft somewhere safe (e.g. the North Sea) and eject. Indeed, quite a few Lightnings ended up in the North Sea, mostly from RAFs Binbrook, Wattisham and Leconfield!

This Sukhoi Su-30 could be going Mach .98 or it could be hovering.

Low Flying for a Living

Crop-dusters, or as they prefer to be called these days – aerial sprayers, know more about low-level flying than any professional pilot on the planet today. Here, Johnny Seay, a Grammy Award–nominated country singer turned crop-duster, locomotive driving sculptor and painter brings his highly-modified Boeing Stearman in for a run just inches from the surface of a field in Texas. If there aren’t any fence posts, high-tension towers, silos, trees, windmills or the occasional horse, then Johnny wouldn’t have any fun. For more information on this crop-dusting Renaissance man, visit his website. Photo via Johnny Seay

What do crop-dusters do in the winter? Try spreading coal dust on the surface of a river to speed up the melting of the ice. Not something you might do in an open cockpit sprayer. Here, a crop-duster spreads dust on the Platte River near Ashland, Nebraska. The black dust absorbs solar radiation and converts it to heat, which helps melt the ice. Photo: Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha Division

There is a fine difference between taxiing and low-level flying. 1000aircraftphotos.com sends us this fantastic image of a Stearman about 6 inches from a high-speed taxi in a field of cotton while his propeller chews through the harvest. “The pilot of this Stearman was 19-year-old George Mitchell, the son of one of the founders of M & M Air Service, located in Beaumont, Texas. The reason the wheels are in the cotton is that George was having a hard time getting work, and this farmer told George that he had watched him working a field the day before and said George was flying too high above the cotton when he was spraying the field. George told him he would fly the field close if the farmer would give him a chance. The farmer did and so did George. George said the farmer was running around, jumping up and down trying to get him to stop because George was wiping out 2 rows of cotton with each pass.” Photo: Ken Smith Collection via 1000aircraftphotos.com

The Mach Loop—Low-Level Nirvana

No story about low-level flying can be considered complete or authoritative without mention of and photographs from the world-famous “Mach Loop” in Wales. This low-level training route through the mountains and Dinas Pass of Wales, known as LFA7 (Low Fly Area-7) to the RAF, is a fighter pilot’s wet dream and a photographer’s mecca. Located in Wales, the Mach Loop is formed by valleys which run between Dolgellau (pronounced ’Dol-geth-lie’) in the north, Tal-y-llyn in the west, Machynlleth (pronounced ‘Mah-hunth-leth’) in the south and Dinas Mawddwy in the east. This route is regularly used by the RAF, USAF and, occasionally, other foreign air forces for low-level training. Approximately 21 miles in length, it takes a fast mover like a Eurofighter Typhoon II about 4 minutes to make the complete loop.

It’s a long hike for aviation photographers, and the published schedules are not always reliable, but many are rewarded by absolutely breathtaking scenery, heart pounding and chest compressing flybys and some of the most stunning photographs available anywhere on the planet. I highly recommend you take a look at some of the videos available on YouTube, but as we are in the second dimension only, English aviation photographer and enthusiast Tim Croton has generously allowed us to use a few of his many images from the “Loop” to illustrate exactly what is in store if you should go.

Even if aircraft never show, you are in heaven and given the gift of this magnificent view to the valley leading up to the watchers spot on CAD West (Cadair Idris West). Here we see the view towards Bala, just where the “V” shape is on the horizon over towards the right. To the left is Dolgellau; both places can have aircraft flying in both directions and from Bala/Dol into CAD. To the extreme right of the photo is where they exit from the Bwlch, again it’s pot luck as to which direction they travel thereafter. Photo and comments: Tim Croton

The imposing and Lord-of-the-Rings-like slopes of Cadair Idris. Photo: Tim Croton

CAD East, the highest point, is known as the “Snake Pit” and one can see the narrow slot aircraft have to negotiate. Photo: Tim Croton

After coming up the valley, through the Snake Pit, aircraft drop to the lake far below. Aircraft either transit over the lake and out to sea or turn left at Corris Corner; if the latter is the case expect them to do a second pass! Photo: Tim Croton

The high bluffs of the Welsh mountains edging the Loop behind this Harrier GR7 from RAF Wittering truly give you the sense of the dangers and skills involved in flying this route. Photo: Tim Croton

If you stand on one particular hill at CAD West (Cadair Idris West), the aircraft rise up out of the valley past you, some in knife edge like this Hawk T2 from RAF Valley (a station on the island of Anglesey, Wales). Here you can see the white gloves of the pilots and practically read their maps. Photo: Tim Croton

From this photo you can see that the Harrier GR9 (from RAF Cottesmore) is actually pulling towards the spot where Croton is standing. There is no doubt that the pilots know the photographers like Croton are there and perhaps pull a little more aggressively. The craggy, fescue covered hills are close behind. Photo: Tim Croton

A pair of Tornadoes tail chase up the valley at a spot called Top Shelf Bwlch (pronounced “bulk”.) The name Mach Loop is actually named after Machynlleth and not the speed of sound. USAF crews call it the “Snowdon Roundabout.” Photo: Tim Croton

The Star Wars plan form of the Eurofighter Typhoon II is best enjoyed at Mach .7 and at eye level! This one is likely from RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire… home of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. Photo: Tim Croton

Having flown in Hercs in a few Tactical Airlift Exercises, I can tell you their drivers like it down low and the navigators love to fly with just a map and a few notes. Here, an RAF Lyneham based Herc rips it up the same narrow slot as the Typhoon. Photo: Tim Croton

Not all great low-level “courses” are in Wales or Scotland. Here, as viewed from the navigator’s seat, an A-6 Intruder flies video game style down the heart of the Grand Canyon with the Colorado River below. This image came to us via another Navy Intruder navigator, Thomas Harnish, who tells us “I’ve seen a couple views like that myself as a former A-6 and EA-6B right seater. I assure you, I had a firm grip on the seat even though both hands were busy with equipment when they occurred.” Photo via tailspintales.blogspot

Even airliners do it

The Human Fly, a stuntman by the name of Rick Rojatt, makes a low pass on top of a DC-8 flown by the legendary Clay Lacy in front of the grandstands between events at the 1976 California National Air Races at Mojave. The aircraft is ex-Japan Airlines JA8002. It was owned and operated by American Jet Industries in 1976.

Clay Lacy was no ordinary airliner pilot. In addition to his Human Fly aero-circus act, he also raced a dragster in his Douglas DC-7 Super Snoopy at the 1971 San Diego Cup Air Races. A post on the Supercar Registry website states “In those days there were 1,000-mile air races and some of the guys thought that the prop-liners, with their speed and fuel capacity, were the way to go. Lacy came in 6th at the 1970 Mojave 1000 in this airplane but was not allowed to race at San Diego because the WWII fighter guys complained about the wake turbulence from the DC-7.” Imagine an air race of prop liners! Photo: The Supercar Registry

A Boeing 707 of Air Zimbabwe, flown by Captain Darryl Tarr doing a low-level, high-speed flypast in Harare in 1995. According to witnesses, this was not the lowest the pilot flew. Tarr says that his radar altimeter read 10 feet beneath his keel at one time. He recounts the true facts of the flight in fine detail in Boeing 707 Display Flight.pdf.

The Avro Tudor II G-AGSU makes an extreme low-level pass. Photo: Flight Global

No low-level pass down the runway could be better that the clattering approach and Harley-esque pass of a venerable and beautiful Douglas DC-3. To witness this simple and timeless flypast at just 12 feet is a gift from God.

An American registered de Havilland Canada Caribou does an extreme low-level air drop at a New Zealand Army forward operating base in Afghanistan. On another pass, the Caribou hit the flag pole but managed to recover safely to Bagram Air Force Base in Parwan Province.

A Royal Air Force Lockheed C-130K Hercules gets down in the dunes in Kuwait. Photo: Flight Global

This Russian Antonov An-12 “seems” to take the prize for low-level flight in a large airplane flying at less than 3 feet. You can make out the vortices of the turboprops as she thunders down the snow covered runway. Nothing like an Antonov impaling pole on the edge of the runway to keep you flying the centre line!

Sometime, when an airplane is so low it could be taxiing, well, maybe it’s just taxiing. Photoshop can make a fool out of anyone… good work whoever did it. From one Photoshop guy to another.

A beach makes a good low-level venue

I can’t even imagine how amazing it would have been to be on the beach this day to see a Consolidated B-36 “Peacemaker” fly down the line between water and sand. If he passed right overhead, both wingtips would be a spectacular 115 feet away in both directions. Designed for altitudes in excess of 35,000 feet, the Convair was a rare sight this close to the ground in level flight.

A Douglas Skyraider performs for the troops, possibly on China Beach in Vietnam, judging by the conical hats on the women at left.

With bomb bay doors open and beautiful filthy freedom-smoke coming from the 8 engines, this B-52 flies down the beach in its typically nose-low attitude. The white smoke trails are most likely to demonstrate wind drift to the pilot, making this an orchestrated low-level flight.

An Avro Shackleton maritime patrol bomber of 38 Squadron RAF rips up Majunga Beach, Madagascar in 1966, with both port propellers feathered. Photo: Richard Hugo Walker

This photo and the following one are my two favourite shots of low-level flying. A South African Air Force Harvard trainer rips up a beach on the Atlantic coast near Saldanha Bay with its propeller tips no more than three feet from the sandy surface. A group of Army officer candidates walking up the beach are just now realizing that their lives are in jeopardy. In the far distance you can just make out three other Harvards. Thanks to Bayou Renaissance Man

Not sure if this is the first Harvard or one of the three following as the aircraft seems on a different line.

A spectacular shot of a Fairchild C-119 Flying Box Car flying low over sunlit waters… one of my favourite shots! Photo via Blake Reid

Mathematically, you can’t get much lower than two inches below the hard deck. This South African Harvard aerobatic team set the bar as high (or is it low?) as is physically feasible with this wheels in the water formation flypast.

The twin-engined Diamond Star Twin rips along a beach. Judging by the number of cameras at the ready, this was not an unauthorized flyby.

Dramatic footage from a dramatic time. Argentinean pilots showed they were a match for any air force during the Falklands War. This attack is carried out by Grupo 5 de Caza of Fuerza Aérea Argentina flying A-4 Skyhawks just a few feet off the water to avoid radar detection. This particular attack took place on the 25th of May against the HMS Broadsword. Pilots: Captain Pablo Carballo (left); Lieutenant Carlos Rinke (right). Though Argentinean ground forces on the Falklands were conscripts with very little will to fight, the Argentinean Mirage and Skyhawk pilots were given much-deserved respect for their daring attacks.

The Navy loves to do it

Down under, a Royal New Zealand Air Force A-4 Skyhawk flies well below the deck of HMS Invincible (the Harrier “ski jump” can be seen at the right). The photo dates from the deployment of NZ A-4s to Singapore for the “Vanguard” Five Powers Defence Agreement exercise in March 1989. Many thanks to Sam Hall of Wellington New Zealand for the information.

One of the most celebrated images of a low pass is this shot of F-14 Tomcat driver Captain Dale “Snort” Snodgrass making a curving pass alongside USS America. Many web-wags have stated that this was unauthorized, dangerous or that it even was a photo of a Tomcat about to crash. However, Snodgrass explained: “It’s not risky at all with practice. It was my opening pass in a Tomcat tactical demonstration at sea. I started from the starboard rear quarter of the carrier, slightly below flight deck level. Airspeed was about 270 kts. with the wings swept forward. I selected afterburner at about a half-mile out, and the aircraft accelerated to about 315 kts. As I approached the fantail, I rolled into an 85-degree bank and did a hard 5–6G turn, finishing about 10–20 degrees off of the boat’s axis. Microseconds after this photo was taken, after rolling wings-level at an altitude slightly above the flight deck, I pulled vertical with a quarter-roll to the left, ending with an Immelman roll-out 90 degrees and continued with the remainder of the demo. It was a dramatic and, in my opinion, a very cool way to start a carrier demo as first performed by a great fighter pilot, Ed ‘Hunack’ Andrews, who commanded VF-84 in 1980–1988.” Photo by Sean Dunn, http://www.f14flybyphoto.com

A B-52 slides down the port side of USS Ranger (CV-61) in its typical nose down cruise attitude. Though it looks like it, this is not photoshopped. It happened in early 1990 in the Persian Gulf, while U.S. carriers and B-52s were holding joint exercises. Two B-52s called the carrier Ranger and asked if they could do a flyby, and the carrier air controller said yes. When the B-52s reported they were 9 kilometres out, the carrier controller said he didn’t see them. The B-52s told the carrier folks to look down. The paint job on the B-52 made it hard to see from above, but as it got closer, the sailors could make it out, and the water the B-52’s engines were causing to spray out. It’s very, very rare for a USAF aircraft to do a flyby below the flight deck of a carrier. But B-52s had been practicing low-level flights for years, to penetrate under Soviet radar. In this case, the B-52 pilots asked the carrier controller if they would like the bombers to come around again. The carrier guys said yes, and a lot more sailors had their cameras out this time. Photo was taken from the plane guard helicopter

One of our readers, former USAF B-52 commander Doug Aitken, sent us this photo of two Guam-based B-52s flying low past USS Nimitz. The caption on the back reads “Grand Forks bomber over the Nimitz, winter of 81.” The story that comes with this photo makes for a long but very interesting caption — See below

I am a retired USAF pilot who also flew for AA for 17 years. I was an OV-10 Forward Air Controller in Vietnam and got into the B-52 in the second half of my career.

I was the Ops Officer for the 37th BMS, 28th BMW, at Ellsworth AFB in 1979, during the Iranian Hostage crisis. We were surprised with a no-notice Operational Readiness Inspection from SAC Headquarters in early Dec 79. During the prep for that ORI mission, we were halted in our tracks and told to prepare for a deployment to Guam. Six hours after that notice, the first KC-135s were airborne and three hours after that the first three B-52H’s deployed.\

We ended up sending a Squadron’s worth of B-52H’s to Guam -- a mixture of crews from the 77th BMS and the 37th. The deploying crews were led by the 28th BMW Vice Commander, Col Wayne Lambert, and the 37th BMS Commander, LTC Jim Dillon and 77th BMS/DO, Major Bill McCabe.

LTC Bob Murphy, 77th BMS/CC, and I stayed behind with the remaining crews who flew that ORI mission.

At Guam, the deployed crews immediately began training in the conventional missions they were not proficient in -- sea surveillance, mine laying, and conventional “iron bomb” missions. The B-52s stationed at Guam permanently were the “D” model, and while those crews were specifically trained to do conventional missions, their B-52’s did not have the range to get all the way into the Indian Ocean/Persian Gulf. Previously, the B-52H crews at Ellsworth only had a nuclear mission, so for most of them, this was new (we did have a few older members who had flown conventional missions during the Vietnam War.)

This effort went on for approximately a month until all the crews were trained. Then the majority of the crews returned to Ellsworth, and a small staff, led by Major McCabe, stayed with four of the Ellsworth crews. Around the first of the year, I led two more B-52’s as we deployed with staff to relieve Major McCabe and two of the deployed crews. We continued his work in formalizing the training program and started training the new crews.

After being there about a week, we were tasked by the JCS to fly a mission deep into the Indian Ocean/Persian Gulf to surveil the Soviet Fleet. At this time, the US 7th Fleet was in the area, being shadowed by the Soviets, and their Bear bombers, launching from Afghanistan, were harassing our carriers. The JCS evidently wanted to show the Soviets AND the Iranians that our strategic airpower could reach them that far out.

Our small staff, with some assistance from the local staff, planned this mission overnight and launched early the next day. Since the Soviets always maintained an intelligence gathering trawler off the coast of Guam, these two B-52Hs launched in darkness, filed as KC-135s to Diego Garcia, complete with bogus KC-135 crew lists on the ICAO flight plan. Gunners were instructed to leave their radar off, and radar navigators were instructed to use frequencies that KC-135s would use.

The Airborne Commander was Captain Wally Herzog (copied on this message), who was the most experienced pilot available from the local crews. An instructor pilot in the B-52D, he had been the person leading the conventional qualification of the B-52H crews. The two crews, one from the 37th BMS and one from the 77th BMS faced a total of five air refuelings and 30 hours, 30 min of flight time (These missions eventually earned the name “Winchester” missions due to the 30–30 time.) After refueling with tankers based in Diego Garcia, these B-52s flew “due regard” (i.e. no flight plan) into the Persian Gulf.

At any rate, this deception was successful. The crews made contact with the US Navy and were vectored to the Soviet fleet. On their first pass, the Soviet crew were on deck waving, at first assuming the aircraft were their BEAR bombers. On the second pass, not one member of the Soviet navy was to be seen.

The BUFFS then went over and did a flyby for the US Navy, and returned to Guam. The following week, two crews from the 319th BMS at Grand Forks AFB, ND deployed to Guam and we returned the two crews who had flown the original mission. We then flew a second “Winchester” mission with those 319th crews. After that success, I returned to Ellsworth as we were relieved by two more 319th crews and staff." Doug Aitken

A brace of Buffs whistle over a sea of a different kind (sand) on a former salt lake bed in the American Southwest.

As Slim Pickins’ character Major “King” Kong said in Dr. Strangelove: "Well, boys, we got three engines out, we got more holes in us than a horse trader's mule, the radio is gone and we're leaking fuel and if we was flying any lower why we'd need sleigh bells on this thing... but we got one little budge on them Rooskies. At this height why they might harpoon us but they dang sure ain't gonna spot us on no radar screen! "

In 2009, a Navy F/A-18F Super Hornet crew got permission for a low-level demonstration flight as part of the opening ceremony for a speedboat race on the Detroit River. This is what it looked like for Motor City residents. Officials waived rules to allow the Navy flyers to swoop under 100 ft along the waterway. One resident said, “I couldn’t believe how low they flew and how close they came to our building. I’m sure the pilot waved at me.” Photo: AP/The Detroit News, Steve Perez. Originally spotted at the Daily Mail

Hawker Siddeley Sea Harriers of 801 Naval Air Squadron, Royal Navy, execute an enthusiastic low-level pass of the flight deck of HMS Illustrious following their final launch from her deck. The squadron was the last Fleet Air Arm unit to fly the Sea Harrier. Photo: Key Publishing Forums

A German F-104 leaves a crease in the surface of the water in 1985. Photo: Key Publishing Forums

A Belgian F-104 turns out after a high-speed low-level pass. Photo: Key Publishing Forums

On 13 April 2016, Russian fighters and a helicopter pushed the very limit and risked an international situation with extremely low-level passes of the US Navy’s destroyer USS Donald Cook in the Baltic Sea. Over a two-day period, two Russian Su-24 “Fencer” strike aircraft made close-range low altitude passes by the Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer. Photo: US Navy

The Spitfire MK923, belonging to Hollywood actor Cliff Robertson of 633 Squadron fame, and flown by Jerry Billing, does an extreme low pass over a grass strip at his home in Essex County, Ontario. From 1975 through 1994 the Billing air strip was a prime spot to see Jerry practice in MK923. People would line the 5th Concession Road to watch Jerry wring out the Spit. Cliff Robertson, famed for playing JFK in PT 109, died in September of 2011. Photo via Bob Swaddling

The legendary, extraordinary Ray Hanna makes an extreme low-level pass in a Spitfire down pit lane at the Goodwood auto racing track in England in 1998. Sadly, with the death of Hanna, we will not see such feats again.

Ray Hanna was an incredible pilot who flew in many movies including The Empire of the Sun and the TV series Piece of Cake. In this iconic image, Ray Hanna is seen flying under Winston Bridge, County Durham, for the filming of Piece of Cake.

Low level flying ran in the Hanna family. Mark Hanna, Ray’s son and also a “dab-hand” at the art of low level flight, is seen here in a P-51 Mustang leading a formation of warbirds just feet above the ground. Photo via Sarah Hanna

In 1998, Mark Hanna concentrates hard as he takes this Spitfire down into the weeds. The Spit is painted in the markings of 316 City of Warsaw Squadron, and the personal aircraft of Wing Commander Aleksander Klemens Gabszewicz. Photo: John Dibbs via Sarah Hanna

Ray Hanna trims the wheat in a farm field near RAF Biggin Hill. Photo via Sarah Hanna

If you haven’t seen this video over the past five years, you’ve been living in a cave with Bin Laden. One of the best low-level snippets anywhere… click here. Warning… contains high levels of “Fuck-me.” It features the flying of the legendary Ray Hanna

Young and Bored in Gabon

French Air Force-trained fighter pilot Jacques Borne had a military flying career spanning three decades. He was able to continue flying as a fighter pilot from 1960 up until 1990 by contracting out his services as a mercenary with the Gabonese Air Force in the former French colony. At the end of his time in Gabon, Borne had accumulated 1,047.5 hours in the Douglas AD-1 Skyraider, and by these photos supplied by his son Frédéric, a lot of them were close to the ground. It seems from the photos of his time in Gabon that he and his fellow pilots occupied their time by getting down low… really, really low. The benefit of this amusement was to build exceptional skills in low-level flying.

Fighter pilot Jacques Borne learned his low-level chops with l’Armée de l’Air flying the small but nimble Dassault Mirage III E. The supersonic fighter, designed in the 1950s, also flew with many countries including Gabon. Photo via Frédéric Borne

A photo of Borne and a Mirage with l’Armée de l’Air. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Mercenary pilot Jacques Borne in the seat of a Fouga Magister of the Forces Aériennes Gabonaises. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Posing like desperadoes in the summer of 1977, Jacques Borne and his fellow Skyraider pilots, formerly of l’Armée de l’Air and Forces Aériennes Gabonaises, now stand in front of a Chadian Skyraider at a place called Faya-Largeau. Chad is a Central African country which had a civil war that ran from 1965 until 1979 when Muslim rebel factions conquered the capital and all central authority in the country collapsed. The disintegration of Chad caused the collapse of France’s position in the country. Libya moved to fill the power vacuum and became involved in Chad’s civil war. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Borne at the helm of a Beechcraft T-34 Turbo-Mentor helps with the wheat harvest on a Gabonese farm. Photo via Frédéric Borne

A Gabonese T-6 Texan with Jacques Borne at the controls keeps the grass trimmed at a Gabonese airfield. The red roundel at the back of this Texan is one simultaneously used on Gabonese aircraft along with the standard green, yellow and blue one—representing the Presidential Guard Flight of President Bongo. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Long before the South African Harvard team was skimming the still lake surfaces of their country, Borne was dancing across the waters in Gabon in a similar Texan. Photo via Frédéric Borne

The pilot on the Harvard in which the photographer sits qualifies for this story, but Borne in the subject Texan is lower still, with his right tire kissing the water in Gabon. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Borne takes his Skyraider down to 15 feet where the air is nice and dense. One wonders if the stubs of trees were the result of other low-level adventures. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Borne flies by his yacht. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Borne takes his Gabonese Fouga Magister low over a runway. Photo via Frédéric Borne

Flying as a paid contract pilot with the Gabonese Air Force, former Armée de l’Air fighter pilot Jacques Borne, flying a T-34 Turbo Mentor, executes a below-deck pass of an oil rig off the coast of Gabon in the Gulf of Guinea. The Gabonese roundel, like their flag, is blue, yellow and green (centre). Photo via Frédéric Borne

And finally

A silent rush. I leave you with a photo of four young men sitting in the middle of the runway at the Mollis Gliding Club in Switzerland as a slender-winged glider passes low over their heads in a fine unpowered example of low-level flight the length of the 6,000-foot runway. Photo: fly13.co.uk