PADDLE WHEEL FLATTOPS OF THE GREAT LAKES

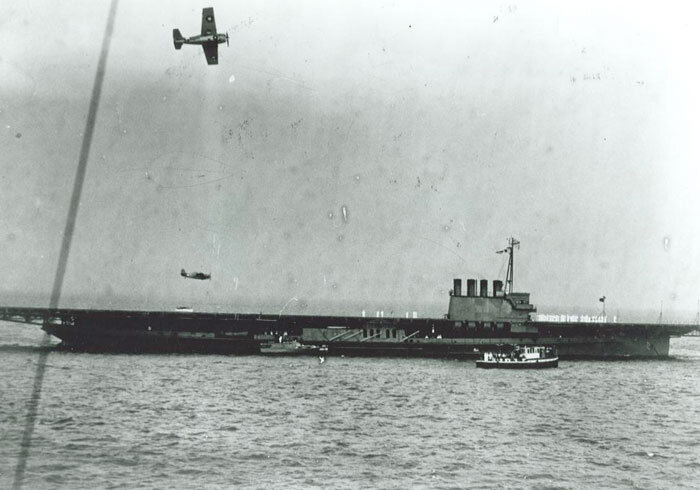

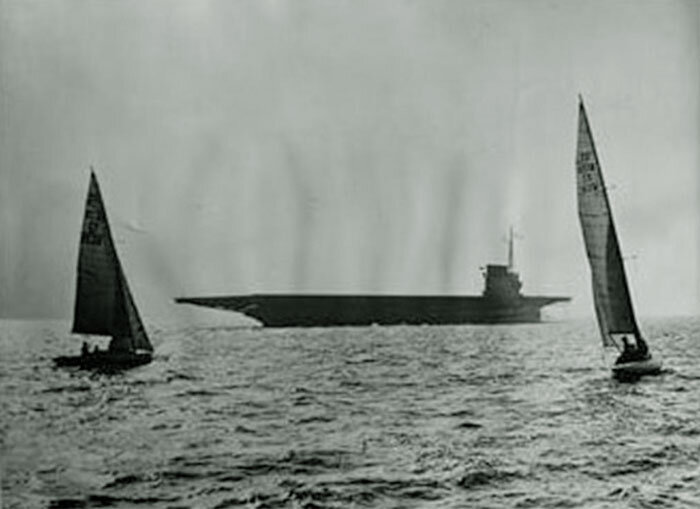

The US Navy training carrier USS Wolverine (IX-64) running her official trials off Buffalo, New York, 11 August 1942. Here we see clearly how close the flight deck was to the water, compared to contemporary Fleet carriers like Lexington. Photo: US Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation

Whenever I picture in my mind the great coming of age of the aircraft carrier, I think of the gargantuan fleet carriers of the US Navy in the Second World War—rust streaked, heaving in cold grey seas, driving through heavy swells under a threatening sky. I see them also on a brilliant day, under a hot white-blue sky stained by the black bruises of a hundred flak bursts, tracers frantically arcing, training on a lone Japanese aircraft piloted by a gritty young flyer who believes he is already dead.

I see the knifing blur of a Zero as it drives deep into the water beside the cliff-like sides of an American carrier, the tumbling remnants of a Kamikaze, throwing out a spiral of red flame and oily smoke. I see a grey steel mesa, bristling with quadruple “forties”, and gun tubs brilliant with hot brass shell casings. I hear the pounding of five-inch guns, the rhythm of the Bofors. I see a distant deck roiling with orange explosions and thick black volcanic smoke rising. I see a helmeted chaplain giving the last rites. I see a white shroud flapping.

These were the carriers with triumphant American names like Lexington, Bunker Hill, Randolph, Saratoga and Essex—30 to 40 thousand tons, 180,000 shaft horsepower, 100 aircraft, 2,500 men. They could be found off mythic islands with haunting names—Tarawa, Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Peleliu and Saipan. These were the legends of my youth, surrounded by task forces, played like chess pieces by admirals, draped in battle honours. These were mighty weapons, ships of the line with an admiral's flag snapping from the halyard. From their bridges, men like Halsey, Nimitz, Spruance and Fletcher gazed out to their destinies.

But there were other carriers. Slow-moving, coal-burning, side paddlewheel ships that had no battle honours, no complement of aviators or their aircraft; no protecting screen of cruisers and destroyers. These were the two land-locked carriers of the Great Lakes, having more in common with Mark Twain's Mississippi riverboats than all-out warfare on the far side of the planet. They steamed under no great threat save winter ice and the famed white squall. They never saw the open sea, never tasted salt water or blood. They did not venture far into the unknown. They berthed at the same dock every night. They didn't knife the water at 30 knots, driven by three screws and 180,000 shaft horsepower, instead they flapped across shallow waters driven by the thump of ancient steam engines and the swishing of leviathan paddlewheels.

They would never see Tarawa or Okinawa, but they were a common sight off Milwaukee, Racine, Muskegon and Waukegan. They took their place in carrier history without guns, armoured decks, hangar decks, catapults, admirals, or a single battle. They were not named after the great battles for Independence, or founding fathers, but bore the names of woodland animals, albeit fearsome ones. These were the coal smoke belching, paddlewheel foaming, freshwater, land-locked training carriers of the Great Lakes—USS Wolverine and USS Sable.

S.S. Seeandbee and USS Wolverine (IX-64)

USS Wolverine, a smoke belching, paddlewheel flattop of the United States Navy, was once an elegant, post-Victorian, side-wheel excursion steamer on the Great Lakes. Built in 1913, she was named S.S. Seeandbee, a name based upon her owners' company name—the Cleveland and Buffalo Transit Co. (C&B). She was constructed by the American Ship Building Company of Wyandotte, Michigan and operated as a luxury excursion steamer on overnight service to Great Lakes port cities.

The United States Navy acquired the side paddlewheel steamer on 12 March 1942 and designated her an unclassified miscellaneous auxiliary, with hull number IX-64. Her conversion to a training aircraft carrier began on 6 May 1942. The name Wolverine was approved on 2 August 1942 with the ship being commissioned on 12 August 1942. Intended to operate on Lake Michigan, IX-64 received its name because the state of Michigan is known as the “Wolverine State”.

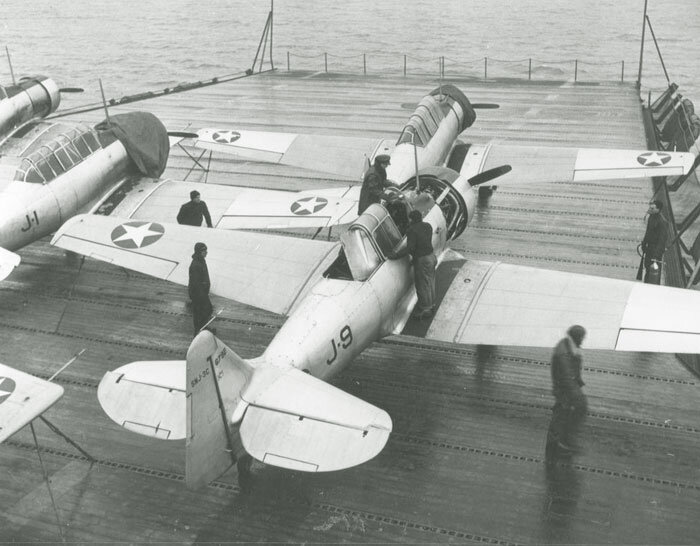

Fitted with a 550 ft flight deck, USS Wolverine began her new job in January 1943, joined by her sister USS Sable (IX-81) in May. Operating various aircraft out of Naval Air Station Glenview, a suburb of Chicago, the two paddlewheelers provided a training platform not only for pilots, but for Landing Signal Officers (LSOs) as well.

Sable and Wolverine were a far cry from frontline carriers, but they were suitable enough for accomplishing the Navy's purpose: qualifying naval aviators, fresh out of operational flight training, in carrier landing techniques. The two carriers lacked certain equipment found on fleet carriers, such as elevators or a hangar deck. If crashes used up the allotted spots on the flight deck for parking damaged aircraft, the day's operations were over and the carriers headed back to their home on Chicago's waterfront, the Navy Pier.

Making only 18 knots top speed, the Great Lakes carriers had operational limits to contend with such as “wind over deck” (WOD). Specific WOD minimums of around 30 knots were required to land combat aircraft such as F6F Hellcats, F4U Corsairs, TBM Avengers and SBD Dauntlesses. When there was little or no wind blowing over Lake Michigan, flying operations often had to be cancelled because the carriers couldn't reach the speed required to meet the WOD minimums. Low WOD speeds were critical on these carriers as the flight deck was relatively close to the water, compared to fleet carriers. Any aircraft not generating enough forward speed on takeoff would experience “sink” once clear of the bow. Many fleet carriers had enough height above the water for the pilot to collect the aircraft and gain flying speed, not so on Wolverine.

If low wind conditions continued over several days, a backlog of waiting aviators grew. The alternative was to qualify the pilots in SNJ Texans which had a lower threshold for WOD—even though most pilots had not flown the SNJ for four or five months. This process sent pilots to operational units without actually having carrier-landed the type they would fly while deployed with the fleet.

When the Japanese surrendered, the carriers were shut down immediately. Wolverine was decommissioned on 7 November 1945. Three weeks later, on 28 November, the ship was struck from the Naval Vessel Register. It was then transferred to the Maritime Commission on 26 November 1947 for disposal. The last records indicate that the ship was sold for scrapping in December 1947.

The USS Wolverine (hull number IX-64) was one of two refitted coal-fired, steam driven, paddlewheel passenger ships that were converted into training aircraft carriers and operated from Lake Michigan. Here we see Wolverine at anchor shortly after her conversion from a Great Lakes passenger liner known as S.S. Seeandbee. When at anchor, she would raise her radio masts, as witnessed by the two masts on her bow rounddown. Two thirds of the way down her side we can see the paddlewheel boxes. The new fresh water flattops were referred to as “training carriers” and were sometimes informally given the designations “T-CV”, but they were actually listed on the navy rolls as “unclassified vessels” with the designation IX-64 (Wolverine) and IX-81 (Sable) respectively. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. NH 45092

USS Wolverine was not always a United States Navy training carrier. Wolverine began her life nearly thirty years before in the age of steam-driven passenger liners as S.S. Seeandbee, a Great Lakes passenger liner offering overnight service between Cleveland, Ohio and Buffalo, New York. S.S. Seeandbee was an “excursion” steamer, taking tourists to see Niagara Falls. In this photo of the four-stacker, we can see the portside paddlewheel, lifeboats and cabin decks as she churns her way on Lake Erie. The elegant steamer was built by the American Ship Building Company of Wyandotte, Michigan, a city known in the mid-20th century for its toy production.

Related Stories

Click on image

The steel hull of the side paddlewheeler S.S. Seeandbee nears completion at the American Shipbuilding Company's yard in Wyandotte, Michigan, November 12, 1912. Photo: Library of Congress via Shorpy

A photograph from 1912 showing the hull of C&B's new steamer Seeandbee with the Stars and Stripes waving proudly from her fantail, minutes away from her sideways launch into the Detroit River. Seeandbee was constructed in Wyandotte, Michigan south of Detroit on the Detroit River. Photo: Library of Congress via Shorpy.com

Looking more like the flattop she would someday become, S.S. Seeandbee slides dramatically from the ways on 9 November 1912 while citizens of Wyandotte watch the spectacle. We can see the paddlewheel housings on either side of the hull. Construction would continue into 1913 when she was completed. Photo: Library of Congress via Shorpy.com

The elegant stern of S.S. Seeandbee as she is being fitted out at Wyandotte. Photo via NavSource.org

The lovely Cleveland and Buffalo Line S.S. Seeandbee makes coal smoke from her stacks in August of 1919. Photo via Wikipedia

A postcard from the early 20th century, touts Seeandbee as the largest and most costly steamship operating on fresh water at the time. It also shows us that her hull was painted green. Image via RubyLane.com

Another postcard showing S.S. Seeandbee approaching the Cleveland and Buffalo Line's pier in Cleveland at what appears to be a disturbing rate of speed.

An aerial photograph of S.S. Seeandbee about to get underway and making steam from her paddle boxes. Clearly, there is something very interesting on the port side of the ship, as all of her passengers are lining that rail.

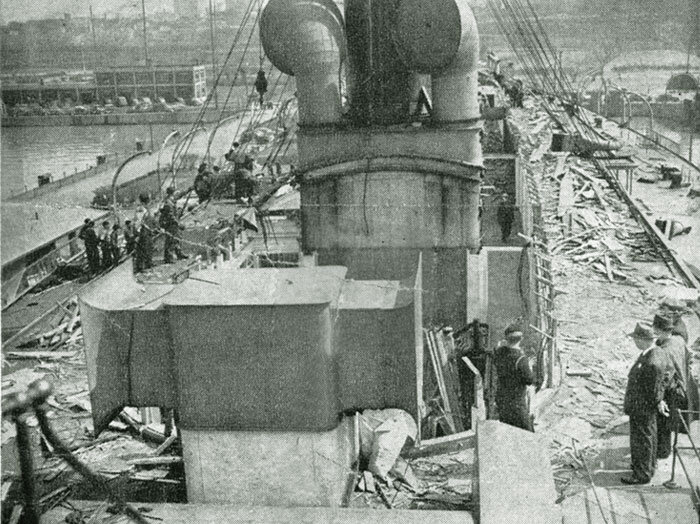

The former grand dame of the Great Lakes, S.S. Seeandbee, looking terribly forlorn, as wrecking crews begin to strip her bare to the gunwales in Cleveland, Ohio in the summer of 1942. The four smoke stacks, which were situated on the centre line of the passenger ship, would now have to be moved to the starboard side of the carrier-to-be to allow room for an unobstructed flight deck. The hull was then towed to Buffalo for the conversion. Scan from period magazine via subsim.com

S.S. Seeandbee tied up at Cleveland, Ohio in 1942, being stripped of her elegant upper decks and equipment during the time of her conversion to a flattop. Scan from period magazine via subsim.com

Shipyard executives and a US Navy officer view the gutting of the once-gloriously appointed S.S. Seeandbee, as she begins her conversion to USS Wolverine. Her uppermost deck has been removed, exposing the interior gallery of cabins and balconies. Scan from period magazine via subsim.com

A photograph of Seeandbee undergoing conversion to USS Wolverine (IX-64) at Buffalo, New York, in early 1942. The massive wooden superstructure, with its former elegant staterooms, stately dining halls and promenades, has been removed and all that is left about at the forecastle deck level is the four boiler uptakes, a structure over the engine room, and the housings for the paddlewheels known as the “paddle boxes”. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. NH 81057

A photo, taken on 2 June 1942 in Buffalo, shows Seeandbee almost disappearing into the conversion to Wolverine. Once the old Seeandbee upper decks had been removed, shipyard work crews moved quickly to add bracing to accommodate the massive flight deck above. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. NH 81058

The old gal went to Buffalo as Seeandbee and emerged as a ship unique in the world—the only paddlewheel aircraft carrier in existence—USS Wolverine. Soon, though, she would be joined by another—the USS Sable. Here she is photographed in August 1942 by the Buffalo, N.Y., Police Department, leaving refit as IX-64 or USS Wolverine. Photo: U.S. National Archives, RG-80-G, No. 80-G-14907

USS Wolverine making revolutions and lots of sooty smoke on choppy Lake Erie while leaving Buffalo after her conversion from S.S. Seeandbee. She left Buffalo, steaming for the Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, the St. Clair River, Lake Huron and finally Chicago at the bottom of Lake Michigan. In this image, also taken by the Buffalo Police Department, we are looking from her stern's port quarter. Wolverine had four coal-fired boilers (hence the four dirt-belching stacks) and generated over 8,000 horsepower to her two side-mounted paddlewheels, allowing her to make 18 knots. A little more than three years later, she would be decommissioned on 2 November 1945, struck from the Navy list three weeks later, and scrapped in 1947. Photo by BPD, U.S. National Archives, RG-80-G, No. RG-80-14909

A fabulous shot of the starboard side of USS Wolverine as she churns over Great Lake waters, with her paddlewheel foaming the surface, taken from a following boat. Her island is barely wide enough to contain the new exhaust stacks.

USS Wolverine shortly after completion with her new ship's complement on parade on deck and one boiler making power to run equipment. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

The USS Wolverine (IX-64) lies at anchor on Lake Michigan in 1943 with the Chicago skyline in background. During the war, Wolverine would remain ported at Chicago until she was decommissioned. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

USS Wolverine at anchor on Lake Michigan on 6 April 1943, from an orbiting Navy aircraft. The tall black structure on her port side is not part of Wolverine, but a tender of some sort alongside. You can just make out a wisp of smoke coming from the tender's black stack. Wolverine, as evidenced by this aerial photograph, had a fairly large flight deck for a land-locked aircraft carrier—500 feet long and 98 feet wide at the waist. Wolverine would be operating on a fresh water lake, with little need for a hangar deck or a large complement of sailors and she drew only 15.5 feet to the bottom of her keel—less than half the draft of a blue-water fleet carrier like her contemporary, USS Lexington (32.4 feet). In comparison, Lexington had ten times the complement of sailors and airmen (2,791 in all)—Wolverine had but 270. Photo: U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation, No. 1996.488.019.009

A US Navy Grumman Wildcat banks over the starboard side of the USS Wolverine (IX-64) lying at anchor on Lake Michigan in 1943, while another Wildcat rips down the port side. The two were likely putting on a display for some event as witnessed by the ship's crew formed up in dress whites on her deck. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

S.S. Greater Buffalo and USS Sable (IX-81)

On 29 July 1942, as the ship that was in time to be commissioned as USS Wolverine (IX-64) was nearing the end of her conversion to a carrier, the United States Navy's Auxiliary Vessels Board convened to assess a report from the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) which stated that additional carrier training capability was still needed in order to meet demand for qualified pilots and that possibly two similar inland freshwater carriers would be needed to fulfill the same training role as Wolverine.

BuAer suggested a phased approach, to build one new carrier along similar lines and a third if required at a later date. The Navy's Bureau of Ships (BuShips) made a recommendation to purchase two additional paddlewheel Great Lakes steamers of similar type to Wolverine, only newer. These were the two famous D&C liners S.S. Greater Buffalo and her sister excursion liner S.S. Greater Detroit.

These two ships, constructed in the 1920s, were the largest passenger ships servicing the Great Lakes and, as of the 1930s, had become the largest side-wheel passenger steamers left in the world. Navy inspectors had confirmed that they were suitable for conversion and that they were in very good physical condition. Both ships were about 30' longer than Wolverine, but were otherwise set up in much the same manner with large steel hulls and massive paddle boxes amidships.

A more complete inspection was made of Greater Buffalo, which had a speed of about 18 knots—similar to Wolverine's. The Board recommended that Greater Buffalo be acquired first and converted along the lines of Wolverine. It was also recommended, since the hull was longer, that the flight deck be increased in length as well and that outriggers and a crane be provided to facilitate the handling of damaged aircraft.

The shipyard began the conversion much the same as with Wolverine. As in Wolverine, the ship was stripped of structure to the hull. A flight deck and island were then built on the hull. Unlike USS Wolverine with her oak flight deck, which was common to all fleet carriers of the day, USS Sable had a flight deck made of steel decking topped with eight types of commercial non-skid coatings. It was a floating test bed.

When USS Sable departed Buffalo on 22 May 1943, she arrived at her new home port of Chicago, Illinois on 26 May 1943. Sable, along with Wolverine, was assigned to the 9th Naval District Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) and was employed in the role of training pilots for carrier operations on fleet carriers. Following the end of the Second World War, Sable was decommissioned on 7 November 1945 and struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 28 November 1945. She was sold by the Maritime Commission for scrap, to H. H. Buncher Company on 7 July 1948 and was reported as “disposed of” on 27 July 1948.

Together, Sable and Wolverine trained 17,820 pilots and took the beating of more than 116,000 carrier landings. Of these, 51,000 landings were on Sable alone. During an inspection conducted by the admiral on 27 October 1942, she briefly flew the four-starred flag of the Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King. One of the pilots qualified on Sable was a 20-year-old Lieutenant, junior grade and future President of the United States of America, George H.W. Bush. Some 130–200 aircraft were lost to accidents during Great Lakes carrier training. So far, 35 have been pulled from the bottom. What is truly astonishing is that in 116,000 carrier landings, almost all by nascent carrier pilots, only 8 men were killed.

Overhead view of the training aircraft carrier USS Sable (IX-81) underway on Lake Michigan with a Grumman Wildcat making a deck launch in 1945. Sable was slightly larger than Wolverine at 8,000 tons with a 535' 5" x 92' flight deck and a hull width of 58 feet and the same shallow draft as her sister ship. She was also equipped with four coal-fired boilers generating about 10,500 hp and 18 knots maximum. As S.S. Greater Buffalo, Sable's four boilers exhausted through three centreline stacks but, after conversion, this was changed to a pair of stacks on the starboard side. Sable's flight deck was made of steel, the first such deck in the US Navy.

USS Sable began her floating life as the side paddlewheel steamer S.S. Greater Buffalo, of Detroit and Cleveland Lake Lines (D&C). Her name was carried wrapped around the wheelhouse, while her bow announced she works the Detroit to Buffalo Division service. In this dramatic photo, she pours black smoke from her funnels as her paddlewheel churns Lake Erie into a froth.

A period brochure, from the 1920–30s, brags they were the two largest paddlewheel steamers in the world. The buffalo head icon makes sense for Greater Buffalo, but the frog representing Greater Detroit must refer to Detroiters’ fascination and demand for frog’s legs as a delicacy in the early part of the 20th Century.

A vintage postcard of S.S. Greater Buffalo. The flip side of the card states: “New Steamers Greater Detroit–Greater Buffalo: The two largest steamers of their type in the world, each having 26 parlors with bath; 130 staterooms with toilets; automobile capacity, 125; 650 staterooms; crew of 300 including officers. The cost of these leviathans of the Great Lakes is approximately $7,000,000.” Image via NavSource.org

Another vintage postcard for S.S. Greater Buffalo

In 1924, a decade after the launch of B&C's S.S. Seeandbee, the Detroit & Cleveland (D&C) Navigation Company launched the two largest Great Lakes side-wheeled excursion steamers ever, the Greater Buffalo and the Greater Detroit. Both were designed by renowned marine architect Frank Kirby and were put into service to provide overnight liner service, transporting up to 1,500 passengers the length of Lake Erie between Buffalo and Detroit. The Great Depression all but wiped out demand for luxury excursions on the Great Lakes and Greater Buffalo was taken out of service and lay idle along with her sister ship Greater Detroit. S.S. Greater Buffalo was 535 feet long and 58 feet wide and as such would be given a second life—to be selected for conversion to USS Sable.

Looking still grand and elegant, S.S. Greater Buffalo is photographed arriving at Buffalo, New York, on 6 August 1942, ready for her transformation to USS Sable (IX-81). This would require removing all of her structure down to the hull. It is sad that there no longer exists such an elegant old lady on the Great Lakes. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. NH 81066

USS Sable (IX-81) photographed belching her signature black coal smoke and surrounded by broken, early spring ice, around the time of her commissioning in 1943. The location appears to be the conversion yard at Buffalo. USS Sable was acquired as S.S. Greater Buffalo in August 1942, just as USS Wolverine was being commissioned in Chicago. Both carriers were converted at a shipyard in Buffalo. Along with Wolverine, she was decommissioned on 7 November 1945, struck off charge on the 28th and sold for scrap three years later. Photo: U.S. National Archives, RG-80-G, No. 80-G-41716

A photograph of USS Sable taken in similar icy conditions in 1945. Slightly bigger than Wolverine, Sable had similar speed, a narrower beam and a greater length. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Newly completed training aircraft carrier USS Sable (IX-81) moored alongside a Chicago pier on the shore of Lake Michigan during a break in training operations. The image is also telling in terms of the smog created by coal furnaces in a mid-western city in winter. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A sailor on board the Great Lakes grain freighter Joseph Wood heading towards Lake Erie in 1942 takes a photograph of the newly completed USS Sable on her delivery voyage to Chicago. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

USS Sable, possibly tied up at Port Colborne, at the mouth of the Welland Canal as it enters Lake Erie. The ship appears to still be under conversion. Port Colborne lies about 20 miles from Buffalo on the Canadian side. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A strange scene on the Great Lakes today, but not in 1943—USS Wolverine steaming past a pair of sailboats in the summer of 1943. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

This and the following photo were taken of USS Sable in 1944. In both shots we can see the unique wake signature of a paddlewheel carrier with white turbulent water halfway down the hull's side where the wheel boxes were. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. NH 43716, also 80-G-354766

USS Sable's deck was originally planned to be made of Douglas fir, as was USS Wolverine's. The United States Navy instead opted for a steel flight deck and to use it as a test bed. The patchy surface of the deck in this photograph is due to the testing program by the Navy of different non-skid materials (like those paint test strips areas you sometimes come across on highways). On the flight deck forward of the island, a USN Grumman Wildcat seems to be in trouble, having pitched up onto its nose after striking the wire barrier. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

Most of our imagery of United States Navy carriers in the Second World War centres around the South Pacific. This image taken from USS Sable in 1944 looks out over an endless expanse of broken ice under a brilliant sun, a scene so common to Lake Michigan in winter, but far from the image we have of Fleet carriers operating off Okinawa or Iwo Jima. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A photograph of USS Sable at anchor off Traverse City, Michigan on 10 August 1943, while conducting test flights of the United States Navy's then-secret TDN-1 drone aircraft. Two of these large twin-engine drones can be seen on Sable's flight deck. The Naval Aircraft Factory TDN was an early unmanned combat aerial vehicle—referred to at the time as an "assault drone"—developed by the United States Navy's Naval Aircraft Factory during the Second World War. Developed and tested during 1942 and 1943, the design proved moderately successful, but development of improved drones saw the TDN-1 relegated to second-line duties, and none were used in operational service. Photo: U.S. National Archives, RG-80-G, No. 80-G-38715

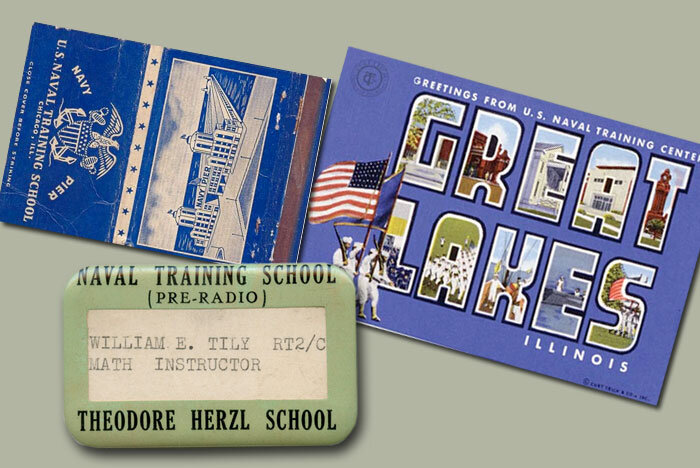

Naval Training School—Navy Pier, Chicago

Home port for USS Wolverine and USS Sable

In mid-1941, in anticipation of looming ‘global conflict, the United States Navy rebuilt the old First World War Navy Pier, which jutted deep into Lake Michigan on the Chicago waterfront, into a Naval Training School (NTS), constructing major facilities including not only classrooms and laboratories, but also gymnasiums, aircraft maintenance facilities, and a drill hall. The technology training school, the largest of its kind in the United States, if not the world, gave instruction to recruits in diesel engine and aircraft engine maintenance and repair, radio technology, and advanced electronics. The facility had sleeping quarters for 12,000 student sailors. Throughout its existence, the Naval Training School provided instruction to nearly 60,000 US Navy ratings. The NTS was also tasked to support operations for the two paddlewheel carriers, Sable and Wolverine. Aircraft operating on the lake-bound carriers took off from nearby Glenview Naval Air Station and flew out to rendezvous with the carriers to conduct launch and recovery training. The NTS operated until the end of the war and was then turned over to the City of Chicago and the University of Illinois. Today, it is an entertainment, commercial and cultural centre for Chicago. Photo via chuckmanchicagonostalgia

The Great Lakes paddlewheel carriers of the 9th Naval District Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) at rest and tied up to the Navy Pier on the Chicago waterfront in the 1940s. Though moored at the pier, both USS Wolverine (right) and USS Sable were attached to Naval Air Station Glenview, Illinois. Located in Glenview, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, the air base primarily operated training aircraft as well as seaplanes on nearby Lake Michigan during the Second World War. Later during the war, NAS Glenview also hosted advanced training in Fleet combat aircraft, primarily for carrier qualification in Lake Michigan aboard the Chicago home ported Sable and Wolverine. Today, the Navy Pier (the long structure in the foreground), is a tourist and entertainment destination with still intact lake terminal (lower left).

A photo of shallow draft USS Sable (right) and USS Wolverine in their home port of Chicago during the war. Parked together we can see the additional length of Sable over Wolverine. The first few hundred feet of the Navy Pier can be seen to the right.

The gymnasium at the Naval Training School on the Chicago Navy Pier was where physical training (PT) was carried out and graduation parades were held for the school.

A postwar photograph of the Navy Pier after the Naval Training School was turned over to the University of Illinois as a technical training centre. The curved roof of the gymnasium can be seen at the far end of the middle yard.

Today, much of the original central training buildings and gymnasium are gone, but the historic buildings at either end are fully restored, a key part of the atmosphere in this historic part of Chicago. Photo via Wikipedia.

Navy ratings undergoing aircraft structure training at the Navy Training School on the Navy Pier during the Second World War.

Some artifacts from the short life of the Naval Training School at Chicago's Navy Pier. From upper left: matchbook from the school, postcard and instructor's name badge. Not all the classrooms attached to the school were on the pier. The Theodore Herzl School in Chicago, a former elementary school and then a junior college, rose to the wartime effort by becoming a naval training school attached to the NTS from April 1944 to December 1945. Matchbook image: chuckmanchicagonostalgia, Badge via Flying Tiger Antiques

The War in the Great Lakes

Naval Air Station Glenview, Illinois

An aerial photo of Naval Air Station Glenview during the 1940s with H-Hut barracks in the foreground. Aircraft operating from Wolverine and Sable were never based aboard the carriers as they did not have hangar space or an elevator. Aircraft, from SNJ Texans to F4U Corsairs would launch from NAS Glenview and fly out to meet one of the carriers cruising on Lake Michigan to make practice approaches, landings and takeoffs, learning to hit a short, moving landing area on a featureless expanse of water and learning to respond to Landing Signals Officers. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Flying Operations on USS Sable and USS Wolverine

The training operations aboard USS Wolverine and Sable were well covered by Navy, American and Chicagoan media photographers, but it seems that Sable got the lion's share of attention. Thanks to the excellent web forum known as Warbird Information Exchange (WIX), we have many of the photographs still extant pulled together in one repository. It was in fact the discussion thread about Sable and Wolverine on WIX that picked our interest in doing this story about a remarkable period in naval aviation history. Sadly, Sable operational photos outnumber Wolverine images 10 to 1, but the following images collected by the contributors at WIX and from other sources give the reader a strong sense of the tremendous amount of activity that was carried out on those big decks out on Lake Michigan back in the war.

While Sable takes the spotlight in still photographs, Wolverine was the star of several newsreels about Navy training. There are a couple of videos available on the web that show newsreel footage of Wolverine in operation. Click HERE to see aircraft landing and taking off from USS Wolverine and HERE to see a great shot of her paddlewheel in operation

While aircraft were never based aboard USS Sable, sometimes they travelled with the carrier in transit to another operating area or for delivery. Here 13 FM2 Wildcats and a North American SNJ trainer are lashed to the deck en route to somewhere unknown. In many of the shots of these carriers operating on Lake Michigan, we can see an escorting plane guard in company with the ship, ready to rescue a hapless pilot in training... they were never short of work. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat finishes its approach to the rounddown of USS Sable as a landing signal gives the pilot the “cut” signal. The pilot flies through the smoky exhaust plume coming from Sable's stacks, cuts the power and more than likely snags a good wire. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Landing accidents were par for the course when training on Sable and Wolverine. Some aviators were lost, more than 130 aircraft as well. Here, deck crews scramble around an FM-2 Wildcat flown by Ensign John E. Hood in 1945. If the bent prop tips tell us anything at all, it appears that Hood has just pitched onto his nose, striking the propeller on Sable's steel deck—a relative fender-bender compared to many. A quick search of the internet revealed an obituary for Hood, who survived the war. It reads: John E. Hood, 90, passed away Sunday, 15 May 2011, at his home in Springfield with his loving family by his side. John was born on 22 January 1921, the son of John and Hazel (Rees) Hood... John served proudly in the United States Navy as a Naval Aviator during WWII. He later worked at the Sangamo Electric Company as the Manager of Employee Relations. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Looking pretty operational in this shot in 1943, USS Sable accommodates a quartet of combat aircraft—Vought F4U-1 Corsair, a Grumman F4F Wildcat, and two Grumman TBF-1 Avengers. The three at the back are spotted and chocked while they warm up, but the Corsair is on the roll as witnessed by the vapour spiral coming off her propeller tips. In the background the plane guard boat splashes steadily though Sable's wake. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

An F4U Corsair on flight deck of USS Sable. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

On a beautiful late afternoon in 1943 on the lake, flight deck crewmen disengage a Vought SB2U Vindicator from the arresting wires following its recovery on board the training aircraft carrier Sable. The Vought SB2U Vindicator was a carrier-based dive bomber developed for the United States Navy in the 1930s, the first monoplane in this role. Obsolete at the outbreak of the Second World War, Vindicators still remained in service at the time of the Battle of Midway but, by 1943, all had been withdrawn to training units like NAS Glenview. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

In 1945, a Flight Deck Officer aboard USS Sable signals the pilot of a General Motors F2M Wildcat to begin his takeoff role. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A group of Landing Signal Officers aboard USS Sable find shelter behind the wind break while one LSO brings in a Navy fighter over Lake Michigan in 1945. Sable and Wolverine were not only used to teach landing skills to aviators, but also to teach LSOs the trade of controlling a fighter pilot, who cannot see forward, and bringing him safely on to the deck. It is possible that this is one of those classes. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

One SNJ Texan trainer takes a wave-off just after another has trapped on board the training aircraft carrier USS Sable. Low sun angles in this image show up the unique paddlewheel wake signature, with churned up water rolling down each side of the hull. We can clearly make out the various non-skid surface material test sections on the flight deck as well. The ubiquitous plane guard boat cruises in the distance. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

USS Sable steams along on a bright sunny day, while deck crews struggle to free a Grumman Wildcat from the wire barrier after an arrested landing. Once again, we can see that there are rope lines with sailors ready to keep the aircraft in check and break its fall—a line of sailors off each wing and one line with a rope to the nose or tail. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Navy flight deck officer standing on the steel deck of USS Sable gives the launch signal to a North American SNJ-5C Texan pilot in 1945. The North American SNJ was a naval-ized version of the T-6 Texan/Harvard with tail hook (just visible in front of tail wheel) for carrier landing training. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

If anything, Sable and Wolverine were smoky vessels. A North American SNJ-3 trainer is photographed taking off from USS Sable in May 1945 during training operations on the Great Lakes. There is no doubt that this airman learning to make carrier landings would not make it to the Pacific War which was to end just three months later. The massive amount of black smoke created by the antiquated coal-fired boilers of the old paddlewheeler, while not affecting this midship takeoff roll, would have certainly affected some landings with aircraft flying up the stern of the ship. I guess that if you kept the smoke to your right, you would be OK for recovery. Photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, No. 80-G-354751

A late model General Motors-built Grumman FM-2 Wildcat in flight over USS Sable which, with no wake evident, appears to be floating dead in the water. General Motors/Eastern Aircraft produced more than 5,000 copies of the FM variant. Grumman's Wildcat production line closed in early 1943 to make way for the newer and more powerful F6F Hellcat but, under license, General Motors continued producing Wildcats for both US Navy and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm use. Late in the war, the Wildcat was obsolete as a front line fighter compared to the faster F6F Hellcat or F4U Corsair. However, they were adequate for small escort carriers against submarine and shore threats and for advanced flying training on Sable and Wolverine. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Making smoke on Lake Michigan with the shore of Michigan in the distance, USS Sable seems to be standing still, as her smoke is blowing forward in this shot. Two Naval Aircraft Factory TDN unmanned combat aerial vehicles—referred to at the time as “assault drones”—were test flown with pilots at the controls from the deck of USS Sable. We can see one drone appearing to be taxiing into position down the deck to the fantail and the second drone on the parking area forward of the island. I say “appearing” because, in fact, the drone is taking off from the stern of the carrier as witnessed by this very interesting video on YouTube which shows tests and crashes of the TDN. I suspect that it was far easier for the TDN to be recovered from a stationary carrier, but why it was flying from the stern I am not sure. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A TDN-1 “manned” drone aircraft gets ready to launch from the USS Sable on Lake Michigan in 1943. The aircraft appears to be on the port side, without takeoff flaps, with ailerons set to a right turn and forward of the island, so is perhaps just warming up. One hundred production TDN-1 aircraft were ordered in March 1942. Despite being specifically designed to be a simple, low-performance aircraft, and despite proving promising in testing, the type was considered to be too complicated and expensive for use operationally. The majority of TDN-1s were used in the test, liaison and training roles, with some being expended as aerial targets. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Grumman TBF Avenger hangs by a thread over the side of aircraft carrier USS Sable while curious sailors look on. The “Turkey” appears to have struck its propeller as well. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Grumman F6F Hellcat hangs over the starboard side near the paddle box, after it ran off the deck and over the edge of USS Sable. Luckily for the pilot, the aircraft hung up on the catwalk. With the paddlewheel churning below, it's clear that operations were not going to stop because of the pilot's plight—that's the job of the plane guard boat off the starboard quarter. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Grumman Hellcat clings precariously to the starboard catwalk running the length of USS Sable's flight deck after the pilot lost control of his aircraft on landing. Given the position of the cockpit, it must have been a big task to extricate the pilot. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Bending an airplane was just part of the training when pilots practiced landings aboard Sable or Wolverine. If it was not for the barrier, many more pilots would have been killed and their aircraft lost. This Wildcat has snagged the barrier, bent its propeller tips and broken its left gear leg in the process. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

On a rainy and cold day in 1945, deck crew scramble from the starboard catwalk to come to the aid of a pilot of an F6F Hellcat (F-30) after it ran off to the right and rolled partially off the deck, dropping its right wheel into the catwalk and shock-stopping the propeller. Given the novice pilots landing aboard, it paid to have your head on a swivel as a deck crew member and be watching all landing aircraft. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Another view of the same incident presented in the previous photograph shows the damage caused when the aircraft veered right and into the catwalk just before the island of USS Sable. It could have been a lot worse. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Ducking reflexively, a photographer and deck crew waiting on the catwalk clear their heads out of the way of a careening Grumman Wildcat on USS Sable in 1944. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Heave-ho boys. Men pulling on lines have been a staple of the navy since the days of sail. Here an FM-2 Wildcat (M-21) is pulled to the ground after losing control and impacting Sable's island structure. It appears that the tail hook was snagged then the hook at the end sheared off as well as the tail wheel. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

All hands gather at the forward flight deck to extricate an FM-2 Wildcat after it crashed and took out Sable's barrier. On this side of the ship, we can see two cantilevered troughs projecting from the flight deck out over the lake. These allowed a taildragger aircraft (or two with folded wings) to be pushed, tail first out over the water and out of the way of the operation on deck. This was a great way to store damaged aircraft like this Wildcat and keep training operations moving. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Personnel surround a damaged General Motors-built FM-2 Wildcat on the flight deck of USS Sable to detach it from the cable barrier and assess the damage. All flying would have to stop while the aircraft was removed and eventually craned onto awaiting barges. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Sailors aboard USS Sable gawk at the damage done to her steel deck after a propeller strike from a Grumman Hellcat pitching up on its nose. Wooden flight decks, while more susceptible to fire, could be repaired very easily after such a strike, but the damage here will require some serious work. Surprisingly the aluminum propeller blade seemed to have relatively little damage. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

After viewing hundreds of photographs from Sable and Wolverine, it became clear that muscle power was often employed to deal with damaged aircraft. Fleet carriers had a crane to assist recovery of similarly situated aircraft, but the two paddlewheel carriers lacked a crane, elevators, hangar decks or any sort of maintenance facilities. Here, sailors on board the USS Sable man three lines and pull an FM Wildcat over onto its wheels after it crashed on the flattop. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

While many may look upon this as a sad moment, it in fact becomes the reason why, today, we have many former United States Navy aircraft being recovered from the bottom of Lake Michigan. TBM Avenger ditches alongside USS Sable and it appears that the crew would survive. The aircraft will sink in relatively shallow, cold water, within sight of land and its location will likely be recorded. It may be a loss for the Navy, but it is a win for the yet-to-be-created warbird industry. The United States Navy still keeps total claim on the wrecks of any former Navy aircraft, anywhere in the world. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Firehose and extinguishers at the ready, deck crew of USS Sable scramble to extricate the crew of a Grumman TBF-1 Avenger after a mishap while underway on Lake Michigan in 1945. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Grumman Avenger in the foreground, an F4F Wildcat and an SNJ Texan are tied down on the flight deck of Wolverine, awaiting the signal to fly off. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Douglas Dauntless takes off from USS Wolverine over an ice-covered Lake Michigan. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Underway on a rainy day with a flight of SNJ-3 Texans on her flight deck, USS Wolverine (IX-64) steams across Lake Michigan. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

An SNJ-3 Texan on the takeoff roll aboard USS Wolverine raises its tail as it thunders down the deck. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

Not all landings were successful. An F4F-4 Wildcat claws for altitude while trying to avoid the island on USS Wolverine in 1943. Each of the two Great Lakes carriers had 8 arresting wires and a wire barrier to catch careering aircraft. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A mishap with a Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat is captured aboard the USS Wolverine in 1943. The pilot has full left deflection on his ailerons, but the result of this roll to the right is almost certain impact with the water. The two Great Lake carriers had flight decks which were considerably closer to the lake surface than those of fleet carriers. Pilots had little time to correct a bad takeoff before striking the water in situations like this, but launches from Sable and Wolverine taught naval aviators to make perfect takeoffs, with little “sink” after clearing the bows.

Crewmen and naval aviators aboard USS Sable gather on the deck and climb aboard a Grumman Wildcat to be photographed from the ship's island in celebration of VJ Day. With Victory over Japan now secured, the young men can now go home to their peaceful lives, some disappointed no doubt that they could not test their metal in combat, others grateful for the chance of a life. At this very moment, Sable and Wolverine were no longer needed and, no doubt, training operations ceased immediately. In a matter of days they were taken out of service. In a matter of less than three months, they both would be decommissioned and shortly struck from service... both would rust, tied up to the Chicago pier until sold for scrap a few years later.

LT C.V. Timberlake, a landing signal officer on board the training aircraft carrier Sable (IX-81), pictured in the cockpit of an SNJ Texan. Claude Timberlake flew fighters and dive bombers off the aircraft carrier Ranger and the escort carrier Santee in the Pacific during the Second World war. After transferring to the Navy's pharmacy section in 1948, he was stationed in Brooklyn and then was deputy director of a Navy medical research lab at Camp Lejeune, N.C., from 1953 to 1958 and was head of the Navy's Pharmacy Service for five years before retiring in 1966. I may not be the best judge, but this Timberlake bears a remarkable likeness to pop singing idol Justin Timberlake... related? Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

An F4U-1 Corsair, perhaps the most advanced naval fighter aircraft of its day, is recovered aboard the USS Wolverine on Lake Michigan. The anachronistic paddlewheelers, pumping out great gouts of black greasy coal smoke were from another age compared to this thoroughbred. The horsepower of the Corsair was almost a quarter of that of the old excursion boat that it was landing on. The power output of USS Lexington, a contemporary fleet carrier, was 180,000 shaft horsepower, nearly 23 times the power of Wolverine. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A NAS Glenview SNJ pilot climbs out of his cockpit following a barrier strike while attempting a landing on the USS Wolverine. Photo via Warbird Information Exchange

A Douglas SBD Dauntless sinks inverted into Lake Michigan after attempting a landing on the USS Wolverine. We can see the flaps and tail hook were down ready for a good recovery. It's unknown whether the two-man crew survived this accident, but the aircraft that went to the bottom from Sable and Wolverine are now one of the greatest treasure troves of warbird wrecks extant. Many of the aircraft that ended up in this type of situation were largely intact when they went under. Most went to the bottom in relatively shallow water compared to open ocean operations, and nearly all their coordinates were recorded in ships logs.

A Douglas SBD Dauntless sinks inverted into Lake Michigan after attempting a landing on the USS Wolverine. We can see the flaps and tail hook were down ready for a good recovery. It's unknown whether the two-man crew survived this accident, but the aircraft that went to the bottom from Sable and Wolverine are now one of the greatest treasure troves of warbird wrecks extant. Many of the aircraft that ended up in this type of situation were largely intact when they went under. Most went to the bottom in relatively shallow water compared to open ocean operations, and nearly all their coordinates were recorded in ships logs.

Elcock's aircraft came to rest on the bottom of Lake Michigan, nose down in 250 feet of water, about 50 miles from Chicago. A salvage team recovered the wreck on 21 November 2009 to be restored and displayed in non-flying condition. Here, Elcock's training Hellcat is hoisted onto the dock in Waukegan. Walter Benjamin Elcock Jr., aged 90, died on Wednesday, 2 February 2011 in Atlanta. He saw action in the Pacific theatre and received two Distinguished Flying Cross Medals. Photo: EPA/TANNEN MAURY, No. 01950298