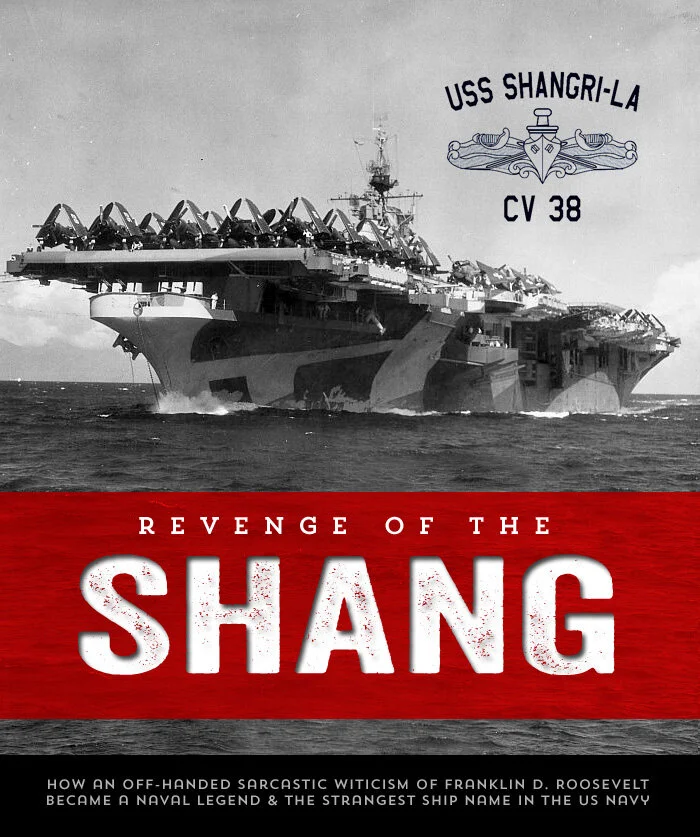

REVENGE OF THE SHANG

When I was a kid, I walked to the library at the Elmvale Shopping Centre every week, dumped an armful of books down the return chute and headed right for the historical stacks where I would stand with my head cocked to the left, scanning the worn spines for titles of books of high flying adventure, the Second World War, the war in the air and the war at sea.

Being a child born just five years after the end of the war, the world around me was still largely textured and coloured by the effects of that conflict. The men who fought that war were all around—the parents of my friends, the men who helped us kids build soapbox racers and tree forts. To us they were old and hard, but they were all still no more than thirty-five years old. There was no direct speaking of the war back then, no show-off dads, no drunken blowhards, but a sense of strength and manifest maleness infused my neighbourhood and the long, long days of my childhood summers.

Standing among the stacks, fighting the desire to go to the toilet, breathing the fecund dust that was shed from a hundred thousand books, my eyes searched for key words on the spines that would cause my hand to rise up and finger-tilt a book off the shelf—Pacific War, Aircraft Carrier, Flattops, War in the Air, Flying Fortress, Kamikaze, Tarawa, Saipan, Malta, Luftwaffe... on and on, week after week. For me, despite the fact that I was a boy of the British Commonwealth, a Royalist, and even a Royal Canadian Air Cadet, the desperate air war in the South Pacific held my attention like no other. Perhaps it was the photo of a burning kamikaze in a spinning death spiral, one wing torn off, oily smoke trailing in spinning loops from a lurid white flame; perhaps the image of Chaplain Joseph O’Callahan giving last rites aboard USS Franklin; perhaps it was the images of the great rusting, heaving hulks of American carriers looming in the massive swells of a post-typhoon wind or the compelling photographs of wounded carrier aircraft crashing onto the decks of carriers and shrieking down the deck to collide with the island or other aircraft. Something both frightened me and kept me in its spell at the same time. It was lively and deadly all at once. It was carried out in green blue waters beneath a hot white sun, but because of the black and white photography of the day, it was forever desperate and gloomy. The contradictions were everywhere: death and life, beauty and obscenity, hatred and love, violence and peace, the vastness and the claustrophobia. Even the words “Pacific War” was an oxymoron not lost on a boy who studied Latin.

Along with the raising of the flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, this image from newsreel footage, taken after Japanese dive bomber attacks on USS Franklin (CV-13), was one of the most powerful and provocative images of the Pacific War. It shows Father Joseph O’Callahan giving last rites to a sailor by the name Robert C. Blanchard aboard Franklin moments after the attack. In March of 1945, Franklin was severely damaged by bombs and more than 800 of her crew died in the ensuing explosions and fires. Both Blanchard and Franklin survived their wounds, with the carrier becoming the most heavily damaged carrier to survive the war. She never saw action or service again though. O’Callahan received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions that day. Photo: Albert Bullock

knew all the big fleet carriers by name, thought about their crews, their brutish fighters and bombers, their long cruises, the hot sun, the blue Pacific and their brief and horrific actions. Above all, their names created in my mind images of heroic strength, desperate fights, young men, grizzled admirals, exposed moments and explosive smoking, flaming deaths. A boy’s imagination could indeed run wild. To this day, just seeing the names Bunker Hill, Randolph, Kearsarge, Antietam or Saratoga brings those childhood endorphins racing up through my bloodstream once again. Those proud names. Those calling cards of history.

Though Canada once operated its own proud aircraft carriers from the end of the Second World War until the 1970s (Warrior, Magnificent and Bonaventure), it can be firmly said that there were only three big operators of the aircraft carrier since the inception of the concept: the United States Navy, the Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy. There is no doubt that I will get a note from someone who feels that I should have mentioned the carriers of Canada or the Royal Navy in this story. Consider it done. This is a story about one Yankee Essex-class Fleet Carrier with a very strange name, and nothing else.

Naming a ship of the line is a process and an honour long steeped in tradition, history, heroism, national pride and naval bureaucracy. In a navy such as that of the United States, a ship might carry a name passed down from ship to ship to ship. For instance, during the Second World War, the American aircraft carrier USS Hornet, which seemed so aptly named, considering the sting of its flying warplanes, was in fact the seventh Unites States Navy ship of the line to be called that name. Her sister carrier, USS Wasp was the eighth American ship to carry that name. The first bearers of those names were sailing ships of the Revolutionary War—Hornet, a 10-gun sloop and Wasp, an 8-gun schooner. Both carriers would be lost in the war against the Japanese and replaced before war’s end by new, larger fleet carriers of the same names.

Prior to the Second World War, and largely throughout, American fleet aircraft carriers were named in succession after previous ships of the line or after the great battle victories of American history. Of the former group, there was Enterprise, Independence, Intrepid, Essex, Hornet and Wasp and later Bonhomme Richard, Cabot, Franklin, Kearsarge and Randolph and from the latter naming convention (famous American battle victories), there was at first Saratoga, Princeton and Yorktown. Later would come legendary names such as Bunker Hill, Antietam, Bennington, Ticonderoga and Bellau Wood. Battles just won during the Pacific War became the names of carriers meant to finish the Japanese off at the end of the war—USS Midway, Leyte and Coral Sea.

There was one aircraft carrier however, whose name seemed to defy all naming conventions of the day—the USS Shangri-La. Its name always seemed strange to me, out of place, exotic, fanciful. For years, I wondered why this one aircraft carrier was named after a fictional Himalayan Lamasery—a place of peace, tranquility, introspection and eternal youth. Turns out her name is one of those times when life imitates art.

Shangri-La is the name of a fictional utopian Himalayan Lamasery in a hidden valley of the same name from the best-selling novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton. The book, published in 1933, captured the imagination of the world, and largely because it was one of the first paperbacks of the Pocket Book series, it became one of the best selling, best loved and most enduring novels of the 20th century. The suffix “-La” is the Tibetan word for “pass” or road through a mountain range. Other non-fictional passes in Tibet include Dongkha La, Jelep La, Lanak La and Nangpa La.

There is no doubt that Lost Horizon was one of the favourite novels of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as he chose Shangri-La as the name for his newly constructed Presidential retreat at Hi-Catoctin, Maryland—the bucolic retreat we now know as Camp David. Roosevelt, when questioned by the press about the location of his new vacation retreat, said somewhat circumspectly, “I might have several. One might be called ‘Shangri,’ and the other might be called ‘La.’ ”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt must have been quite taken by James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (1933) or by the subsequent smash hit motion picture adaptation by Frank Capra. He not only inadvertently named the carrier that was to replace Hornet, but he chose the same name for his new Presidential Retreat, the place we know today as Camp David. Originally a camp for federal employees in Maryland known as Hi-Catoctin, it was selected to build a new spot where Roosevelt could rest without security issues. The camp was renamed the USS Shangri-La, to follow up on the nautical connection, since many workers involved with the building of the Presidential Yacht, USS Potomac, worked on the camp. President Dwight D. Eisenhower renamed it Camp David in honour of his grandson during his presidency. It’s too bad the name Shangri-La did not stick as there is far more history, both military and cultural, associated with the name. Photo via Whitehouse website.

Related Stories

Click on image

Roosevelt also referenced the Tibetan lamasery one other time: after James Doolittle’s famous and daring raid on Tokyo using B-25 bombers launched from the carrier USS Hornet. The Doolittle Raid, on 18 April 1942, was an aerial attack by the United States Army Air Force and the United States Navy on Tokyo and other targets on Honshu Island during the Second World War—the first air raid to hit targets on the Japanese Home Islands. It demonstrated (primarily to the Japanese) that Japan itself was vulnerable to American air attack. As a slap-in-the-face retaliation for the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, it gave a huge boost to America’s homeland morale, and damaged that of the Japanese. The news of the raid and the fate of the airmen involved electrified the American public, giving them the first sense that victory would someday be theirs.

16 B-25 Mitchells, secured to the deck, with Perspex turrets covered in tarps, make the journey towards Japan. The aircraft in the forward positions are having their engines run up to keep them ready for the mission ahead. Photo: US Navy

On 18 April 1942, the fleet carrier USS Hornet (CV-8) launches the first of 16 B-25 Mitchells for the famed Doolittle Raid, the surprise attack on Tokyo that inspired a nation and gave some hope that the Allies could and would strike back. The Hornet was the seventh ship of the United States Navy to carry that name. While it was the first aircraft carrier to launch a medium bomber like the Mitchell, it would be two more years before a Mitchell would land on a carrier... the USS Shangri-La. Photo: US Navy

The raid itself was a huge success, even though none of the aircraft survived, all having crash-landed or were bailed from. As surviving crews were still finding their way to safety in China, not much was said about the raid’s technical aspects at first, but the press were told of its success and impact. When interviewed by the press in Washington, three days after the raid, President Roosevelt answered questions about how the aircraft got to Japan but was reluctant to reveal any details at all, choosing instead to offer a wisecrack that would set in motion the legend that is now USS Shangri-La. Here, from the American Presidency Project, is a transcript of the press conference at which Shangri-La was born:

Q. How about the story about the bombing of Tokyo?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, the only thing I can think of on that is this: you know occasionally I have a few people in to dinner, and generally in the middle of dinner some—it isn’t an individual, it’s just a generic term—some “sweet young thing” says, “Mr. President, couldn’t you tell us about so and so?”

Well, the other night this “sweet young thing” in the middle of supper said, “Mr. President, couldn’t you tell us about that bombing? Where did those planes start from and go to?”

And I said, “Yes. I think the time has now come to tell you. They came from our new secret base at Shangri-La!” (Laughter) And she believed it! (More laughter)

Q. Mr. President, is this the same young lady you talked about—(loud laughter interrupted)

THE PRESIDENT: No. This is a generic term. It happens to be a woman.

Q. Is it always feminine? (Laughter)

THE PRESIDENT: I call it a “sweet young thing.” Now when I talk about manpower that includes the women, and when I talk about a “sweet young thing,” that includes young men...

Q. Would you care to go so far, Mr. President, as to admit that this Japanese—

THE PRESIDENT: (interposing) Wait a minute–wait a minute. “The President Admits”—there’s the headline. (Laughter) Go ahead now.

Q. Would you care to go so far as to confirm the truth of the Japanese reports that Tokyo was bombed?

THE PRESIDENT: No. I couldn’t even do that. I am depending on Japanese reports very largely. (Laughter).

A lobby card poster for the Frank Capra motion picture Lost Horizon depicts the moment that Tibetan citizens and monks find a crashed Douglas DC-2 in a frozen valley near the hidden lamasery known as Shangri-La. Both the book by James Hilton and the film adaptation were massive cultural phenomenons of the late 1930s. In a nutshell, the storyline is explained by the website CultureCourt.com: “Five people are kidnapped when escaping a local revolution in Baskul, China. Instead of being flown to Shanghai, the DC-2 continues east into the mountains beyond Tibet where it runs out of fuel and crashes in the snowy mountain col of an unknown Himalayan range. The mysterious hijacker dies in the cockpit, the passengers survive... but what could their fate be other than a frozen, anonymous death? Out of the deadlight of the endless snow a party of rescuers materialize, led by the enigmatic Chang, who, it appears, has been expecting them. Explanations are left for another time. The five passengers are roped together like slaves and led across the treacherous mountain precipices to a cave, which opens like a dream onto the verdant valley country of Shangri-La.” Poster: Columbia Pictures

The opening title from the motion picture offers the promises of high mountains and powerful vistas. Screen capture: Columbia Pictures

In the book, Lost Horizon, James Hilton tells the story of a crashed passenger aircraft, lost in the Himalayas, with no hope of rescue. That aircraft was portrayed in the ensuing feature film by a Douglas DC-2 rented by the film’s producers from American Airlines. The aircraft had much more than a cameo appearance in the film with lots of great footage of it flying in mountainous territory. Screen capture: Columbia Pictures

Throughout the first third of the twentieth century, there was strong western interest in Tibetan Buddhist and Himalayan culture, the Himalayas, Mount Everest and Tibetan lamaseries. The struggles and eventual death of George Leigh Mallory, on the North-East ridge of Mount Everest in 1924, generated a global fascination with the utopian idea of a simple, peaceful life, longevity, and spirituality at the roof of the world. The set imagined by Capra for the movie seems to take more inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright than from any real Tibetan lamasery. Screen capture: Columbia Pictures

In a scene from the motion picture Lost Horizon, exhausted and near frozen passengers stand in awe as they gaze upon the sight of fictional Shangri-La. The motion picture first opened in 1937 and, by the time of the Doolittle Raid, was well settled into the consciousness and cultural/pop sensibilities of the American and Western publics. Screen Capture: Columbia Pictures

It is not clear who in the Department of the Navy came up with the idea to build an aircraft carrier with the name USS Shangri-La, but it seems that the idea took root after the USS Hornet was sunk in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942. She had been heavily damaged by dive and torpedo bombers and was under tow, when the orders were given to scuttle her because of the proximity of enemy ships. American warships pounded her with nine torpedoes and more than 400 rounds of 5-inch shells from two destroyers. She was still floating when a Japanese task force was spotted in the area and the American destroyers were forced to exit.

Upon finding the reviled USS Hornet, the carrier that had launched the Doolittle Raid six months earlier, the Japanese briefly considered hooking up the carrier and dragging her home as a war prize and morale booster for the homeland. A quick assessment proved the carrier too damaged to attempt capture and she was dispatched with four Long Lance torpedoes from two Imperial Japanese Navy destroyers. She is still, today, the last US Navy carrier to be sunk by enemy action.

Regardless of whose idea it was to select one of the planned Essex class long-hull carriers to be named USS Shangri-La, it was a brilliantly creative idea that captured the imagination of a nation—enough that they would raise over $130 million, one dollar at a time through the sale of War stamps.

War savings stamps were issued by the United States Treasury Department to help fund the overall war effort and sometimes special projects like the Shangri-La. When the Treasury began issuing war savings stamps during the Second World War, the lowest denomination was a 10 cent stamp, enabling ordinary citizens to purchase them. In many cases, collections of war savings stamps could be redeemed for Treasury Certificates or War Bonds.

I found a number of articles in newspapers across America from mid-to-late 1943 concerned with the War stamp campaign to raise funds for the construction of USS Shangri-La. Each quoted local leaders like the city mayor or a business leader. They all followed a similar tone and structure and several had paragraphs with exactly the same wording, word for word. This leads me to believe the community leaders were reading from a prepared text from the Treasury Department. For the most part the news pieces went something like this story I found in the St. Petersburg Evening Independent of 3 July 1943:

Patterson Urges Support of War Stamp Campaign

Chance to Heap More Trouble on Japs, He Asserts

Current campaign of city merchants to sell $1 of War stamps to every man, woman and child in the city during the month of July brought an appeal today from mayor George S. Patterson, who urged that citizens get into the scrap to build the mystery plane carrier Shangri-la for a new crack at the Japs.

Mayor Patterson pointed out that this campaign is in addition to the regularly monthly campaign for sale of War bonds.

He said: “Every resident, man, woman and child of St. Petersburg is burning with ambition to personally exact American justice for the treatment accorded some of the boys captured by the Japanese after the historic raid on Tokyo by General Doolittle and his fliers.

We have a special opportunity to do so in July by buying at least $1 in War stamps to help pay for another mystery carrier Shangri-La [sic].”

“None of us need to be reminded of the origin of the name of the Shangri-la. When President Roosevelt designated the take off point for the Doolittle fliers as Shangri-la to the chagrin of Tokyo he gave birth to the idea of a carrier by that name.”

“The U.S.S. Hornet, the Shangri-la from which our bombers flew toward their objectives, is no longer afloat. However, in her place will sail another Shangri-la.”

“I am sure I speak for the whole community when I say that we will more than meet our quota in War stamp sales. It will be a rare privilege for our citizens to make the purchase of $1 in war stamps in memory of eight boys who flew to immortality. The Shangri-la will be a symbol of our reverence for them. It will be a fighting symbol because from her decks will soar more bombers to blast the savage Japanese war lords from this earth.” [I found this identical paragraph in stories across the country–Ed]

“I appeal to the residents of St. Petersburg as your mayor to take your change in War stamps every time you shop in July.”

“This is a special campaign. It is something additional to our regular War bond buying. The Shangri-la will come to life as a special war effort. It is something extra we will be throwing into the fight.”

St. Petersburg Evening Independent, July 3, 1943

“Bomb Tokyo with Your Extra Change!” In 1942, Roosevelt’s Shangri-La witticism was well known and well appreciated in America, enough to inspire the name of the ship and even a war bond and stamp drive to raise funds to build the carrier to avenge the loss of the Hornet. According to an article in the St. Petersburg Times of 31 July 1943, the local community’s goal in the drive was $60,000.00, with the national goal being $131,669,275.00 and Florida’s portion being $1,397,414.00. The article also stated that “War stamps purchased in July all over the nation will go to pay for the carrier, to replace the Hornet from whose deck went Jimmy Doolittle and his men to bomb Tokio [sic]. The Hornet was later sunk. The new carrier’s real name will never be known until after successful action at sea. Until then, it will be the “Shangri’La,” bought and paid for by public contributions.” This is the first and only place I had read that the name Shangri-La was supposed to be a temporary one. One wonders if this was true, or even what people thought was true back then.

Just a few moments browsing in the right places on the web will bring up several similar stories of campaigns to match the quotas suggested by the Treasury Department for cities and states. It makes for compelling, if repetitive, and somewhat jingoistic reading. The end result was that the money, possibly more, was raised to build a new Essex class long hull carrier that was already going to be built anyway. By attaching the memory of the lost Doolittle Raiders, the sunken USS Hornet and Roosevelt’s mocking and vaguely misogynistic Shangri-La remarks to the story, the Treasury Department was able to squeeze nickels and dimes from an already cash-strapped citizenry. The electricity first generated by the Doolittle Raid was still strongly coursing through the nervous system of America, and it powered the birth of a new carrier.

USS Shangri-La was set to launch from the Norfolk Naval Shipyard on 24 February 1944. There to christen her was none other than Jimmy Doolittle’s wife Josephine and one of the pilots of the Doolittle raid, Captain Shorty Manch. The rest of the story of the shakedown and fighting cruises of Shangri-La was strewn with coincidences, interesting connections and courage. I had only thought to write a story about the name it was given and the inspiration that was behind one unique name in the annals of Naval aviation. Instead, I found the story of one of America’s greatest aircraft carriers.

On 24 February 1944, USS Shangri-La was launched at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Virginia, with none other than Jimmy Doolittle’s wife, Josephine, breaking a bottle of champagne against her bow. Radio microphones can be seen, and Rear Admiral Felix X. Gygax grabs one and leans it forward to capture the sound of the bottle crashing against the ship, confirming this was a major publicity event. Photo: US Navy via Wikipedia

In addition to shipyard dignitaries, politicians and Mrs. Doolittle, there was one other very symbolic person in attendance. The tall Army Air Corps captain standing beside Mrs. Doolittle was Captain Jacob Earl “Shorty” Manch, co-pilot of crew No. 3 of the 16 Mitchells in Doolittle’s Raiders. Sadly, Manch was killed bailing out of a Lockheed T-33 aircraft near Las Vegas, Nevada on 24 March 1958. Photo: US Navy

Crew No. 3 of the Doolittle Raiders: left to right, Lt. Charles J. Ozuk (Navigator), Lt. Robert M. Gray (Pilot), Sergeant Aden E. Jones (Bombardier), Lieutenant Jacob Manch (Co-pilot) and Corporal Leland D. Faktor (Engineer Gunner). Manch would survive and be able to attend the launch of a brand new carrier named in honour of himself and his fellow Raiders. This image was taken aboard USS Hornet days before the attack. Photo: US Navy

Dragging heavy chains to slow her progress, the seconds old hull of USS Shangri-La slides down the ways at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, while lucky yard workers take the ride at the rails and on the flight deck. One can only imagine what an experience this was for these men and women who had worked so hard to complete her in time to take part in the final victory over Japan. Photo via NavSource (http://www.navsource.org) and Gerd Matthes

The brand new first crew of USS Shangri-La assembles with the ship’s band at the ship’s commissioning ceremony. Somewhere in this group of sailors is Wade Litzinger, whose photographs of life on the Shang’s first combat cruises and test operations. A few of these photos are included in this story. Photo via NavSource (http://www.navsource.org) and David Anderson

All members of the Shangri-La’s first commissioning crew were known as Plank Owners, entitled to claim ownership of a plank on her deck at her demise, and were given a certificate which backed this up. It was dated the day of her commissioning on 15 September 1944 and was signed by her first commanding officer, James D. Barner. Sailor Wade Revere Litzinger kept his certificate which is now proudly kept by his grandson Randy Litzinger. Scan via Randy Litzinger

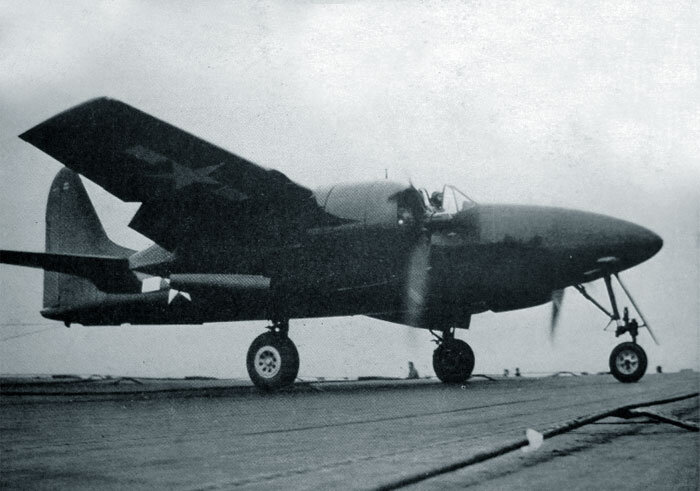

After Josephine Doolittle’s attendance at the launch, the second fact about Shangri-La that, well, blew my mind, was that it was the first aircraft carrier in the world to actually land a B-25 Mitchell. The carrier named in honour of the Hornet, the first carrier to launch a B-25, was somehow accorded the honour of recovering one. On one single day, 17 November 1944, USS Shangri-La, still on her shakedown cruise, trapped and launched, several times each, a B-25 Mitchell, the world’s only navalized P-51 Mustang and the first carrier landings and launches of a Grumman F7F Tigercat. Her war record is stellar, taking part in the Okinawa campaign as well as direct attacks on Tokyo, living up to her promise to avenge the deaths of the airmen lost in the Doolittle Raid and to the 140 sailors who died in the attack on Hornet. After the war, she would be the first American carrier to receive an angled flight deck.

Today, there is only the story of USS Shangri-La left to mark her passing. James Hilton’s fiction is still one of the finest books of the 20th century, but now Shangri-La is fictional no more. The Tibetan mountain town of Zhongdian has now officially renamed itself Shangri-La, claiming both the inspiration behind Hilton’s fictional locale and the tourist dollars it might bring. Fair enough.

What follows are images and stories of USS Shangri-La... the mystery ship.

One of the most astonishing coincidences for the Shangri-La was the fact that, during her shakedown cruise, she was employed as a test platform to both launch and recover a US Navy B-25 Mitchell (called a PBJ-1H by the Navy). Given that her name came directly as a result of the carrier-based B-25 Doolittle Raid, it was not lost on naval people of the day that she would be the first to recover one on board. This image looks to have been taken shortly after the Mitchell has trapped and then released her arresting wire. These tests took place in the Chesapeake Bay area, close to the Norfolk yards.

During carrier trials for the PBJ-1H Mitchell, sailor Wade Litzinger brought his camera on deck, and from the catwalk along her flight deck, took a photograph of one of the Mitchell’s landings aboard Shangri-La. This would be the heaviest aircraft brought to a stop on an American carrier to that point. The pilot was Lieutenant Commander H.S. Bottomly. The tests were for an anticipated need to bring attack bombers like the Mitchell up close to the Japanese homelands in the event of a fight to the end. Photo: Wade Litzinger

Lieutenant Commander Bottomly lands the Mitchell aboard an aircraft carrier for the first time in history—17 November 1944. On that very same day, Shangri-La also landed on and launched a P-51 Mustang and a Grumman F7F Tigercat twin-engine fighter. The Mitchell had been fitted with a tail hook and had been strengthened to take the strain of the trap. It also had unique wheels that could be partially rotated to decrease turning radius on the deck. Bottomly actually aborted his first attempt and had returned to Norfolk for repair. In the end, he would make three traps and three launches. Photo via Shangri-La Cruisebook

With every available viewing position occupied in the Shangri-La’s island superstructure, the US Navy PBJ-1H Mitchell gets ready for one of her three launches from USS Shangri-La. The aircraft would be launched well forward of where Doolittle started his run two and a half years before—with the aid of a catapult. Photo via Mission4Today.com

On the very same day that Bottomly flew his PBJ-1H Mitchell out to trap aboard the Shangri-La, North American Aviation also tested another of their famous types—a navalized variant of their P-51D Mustang called the Seahorse. This one-off fighter (USAAC S/N 44-14017), like its stablemate, the Mitchell, was strengthened and equipped with a tail hook. Here we see the world’s only Seahorse trapping aboard Shangri-La. Photo: US Navy via Shangri-La Cruisebook

With the multiple launches and recoveries of the PBJ-IH Mitchell, P-51 Seahorse and F7F Tigercat, this had to be one hell of a day for hanging out on the island superstructure. Here we see Navy Lieutenant Robert Elder taxiing forward after landing aboard the carrier Shangri-La. Photo: Wade Litzinger

USS Shangri-La’s newly minted deck “airdales” wait to pull the chocks as Lieutenant Elder warms up his P-51 Seahorse before taxiing to position for flying. This is at the back deck of Shangri-La as we can see the arresting wires in this shot. Note the arresting hook at the tail, behind the tailwheel. Photo: US Navy

The one and only North American P-51 Seahorse is seen from Shangri-La’s island superstructure as she rolls down the deck during one of its launches. We can tell it is in the launch as its tail wheel is just rising off the deck and the arresting wires have all been slackened so that the fighter can roll over them. The waist elevator, see at top right is just abeam the island, putting the Seahorse about halfway down the 888-foot-long deck. Of Elder’s experience with the P-51 Seahorse, aviation writer, artist and historian Gaëtan Marie writes: “During the months of September and October 1944, Lt. Elder made nearly 150 simulated launches and landings with the ETF-51D. Sufficient data concerning the Mustang’s low speed handling had to be gathered before carrier trials could begin. The Mustang’s laminar-flow wing made for little drag and high speed but was relatively inefficient at low speed, resulting in a high stall speed. As the arrestor cables could not be engaged at more than 90 mph, Elder reported that “from the start, it was obvious to everyone that the margin between the stall speed of the aircraft (82 mph) and the speed imposed by the arrestor gear (90 mph) was very limited.” ” Photo: US Navy

For any aviation enthusiast, to be aboard USS Shangri-La on 17 November 1944 on the surface of Chesapeake Bay, would have been the thrill of a lifetime. On that one day, test pilots Lieutenant Commander H. Syd Bottomly in his PJB-1H Mitchell, Lieutenant Robert Elder in his P-51 Seahorse and Lieutenant Charlie Lane in a Grumman F7F-1 Tigercat landed and took off several times each. Lieutenant Lane, from the Ship Experimental Unit of the Naval Aircraft Factory (SEU/NAF), made landings and launches that day that were the first ever for a twin-engine, tricycle landing geared aircraft from the deck of a carrier. Lane made both deck-run and catapult-assisted takeoffs that day. Lane’s Tigercat is photographed by crewman Litzinger in repose after trapping aboard, with its tail hook dropped. Photo: Wade Litzinger

Lieutenant Charlie Lane traps aboard USS Shangri-La in his Grumman F7F-1 Tigercat. We can see the tail hook fully engaged with an arrestor wire and that the seemingly delicate nose wheel oleo is compressed, compared to the exposed amount of shaft in the previous photograph. Though the F7F-1 was successfully tested for carrier landings that day, no F7F-1s would ever operate from carriers. Later marks like the F7F-3 would make it back to the carrier deck after the war. Photo: US Navy

USS Shangri-La steams in the Caribbean near Trinidad in the British West Indies—late November or early December 1944. She sports a new coat of camouflage “dazzle paint” designed to break up her lines and confuse submarine commanders as to her identity, speed and direction. On her deck sits what looks to be her complement of Corsairs, Helldivers and possibly Avengers. She would lose this paint scheme when she got to Pearl Harbor. It was during the earlier part of this shakedown cruise, while still in Chesapeake Bay, that Shangri-La had the distinct honour of being the first carrier to launch and recover a B-25 Mitchell, a P-51 Mustang and a Grumman F7F Tigercat. Photo via NavSource (http://www.navsource.org) and Timm Smith

A supply and fuel ship comes alongside USS Shangri-La in the Western Pacific in July of 1945. By this time she had been in theatre since April and her 5-month-old paint was starting to look pretty rough. On the aft flight deck was can see Curtiss Helldivers ranged, each with the letter “Z” on their tails matching the Shang’s “Z” deck code or group identification letter. Photo via NavSource (http://www.navsource.org) and Robert Rocker

Two Curtiss Helldiver aircraft of VB-85—Bombing Squadron 85 slide up to a photoship for a beauty shot over the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1945. The “Z” on the tails of these aircraft indicate that they were part of Carrier Air Group (CVG) 85, the group assigned to Shang. Photo via warbirdinformationexchange.org

A Curtiss Helldiver of Carrier Air Group (CVG) 85 with its backseater handling a reconnaissance camera. Of the more than 7,000 Helldivers constructed for the US Navy, more than 1,000 were built in Canada by Fairchild and Canadian Car and Foundry. Photo via warbirdinformationexchange.org

On 3 February 1945, ten days before Shangri-La was to arrive at Pearl Harbor en route to Okinawa, the ship was still carrying on training daily—a dangerous activity. On that day, this Curtiss SB2C-4E Helldiver crumpled in flames during a terrible crash landing during training. The aircraft (Helldiver 80) attempted a landing without flaps, crashed and caught fire. The gunner, seen here at lower right, was thrown clear, but later died if his injuries. The aircraft was assigned to Bombing Squadron 85 (VB-85), which operated from the carrier during the period from April to September 1945. Photo: US Navy

One of Shangri-La’s armourers, and young ordnanceman by the name of Staples, inspects the twin 30 cal. Browning machine guns in the rear seat of a Curtiss Helldiver. Photo: Wade Litzinger

According to Wade Litzinger’s journal, there were two Corsair crashes on Shangri-La which resulted in the tails breaking off and the pilots surviving. On 24 July 1945, a Lieutenant Reed attempted to land a badly damaged Corsair. Having a shell hole in his fuselage behind the cockpit, the tail hook and empennage ripped off when they snagged a wire and remained at the end of deck, while the rest of plane raced down the flight deck and a wing struck a 4 inch gun turret. Then, on 8 August, a pilot named Ensign Max “Doc” Snavley attempted a landing without flaps, caught the 11th wire stretched across the deck and snapped the tail from his Corsair. The aircraft slid to a stop with Snavely unhurt. Looking at this image, with the tail showing Shang’s air group code letter “Z” and the aircraft resting below the island superstructure, my guess is that this is Snavely’s incident. The image was just moments after the crash as we can see Snavely being assisted down from his cockpit. The aircraft was a total loss. Photo: US Navy via VBF-85.com

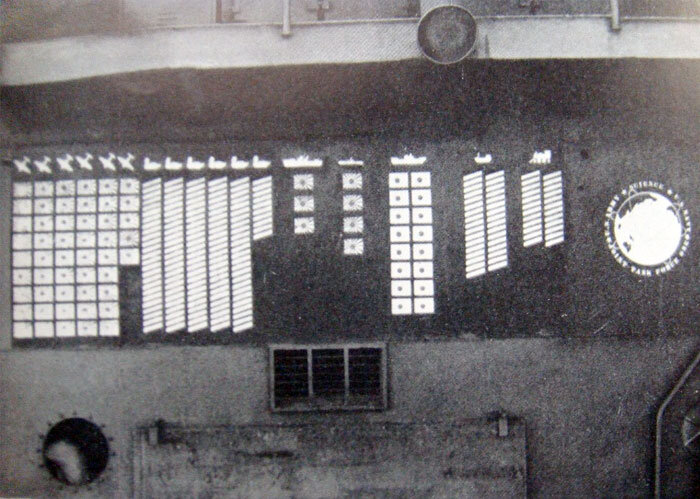

A photo of Shang’s scoreboard shows 50 Japanese aircraft claimed (left) by her Corsair pilots, torpedo and bombing missions (diagonal lines), ships, boats and trains sunk or attacked. Photo via Shangri-La’s Cruisebook

In honour of the surrender of the Japanese just two days before, USS Shangri-La is photographed underway in the Pacific, with her crew paraded and aircraft ranged on the flight deck, on 17 August 1945. She was photographed by her ship’s photographer sitting in the back of a a VB-85 Helldiver. Note use of the Carrier Air Group (CVG) 85 identification letter “Z” on the flight deck instead of her hull number “38” which she would wear for the rest of her career. Photo: Wikipedia

A nice photograph of a VB-85 Helldiver with the ships of her carrier task force arrayed behind. One wonders if this Helldiver was the one that took the previous photograph of Shangri-La as that shot was taken during a mass multi-carrier task force group shot. The carriers and other ships in the background, large format camera and the happy faces of Helldiver crew seem to hint at that. Photo: US Navy

A month after VJ Day, a weathered and veteran USS Shangri-La comes alongside the escort carrier USS Attu. The Shang’s radio masts are deployed vertically for best transmission and reception, indicating there is no flying planned. Soon she would be on her way home to Bremerton, Washington. Photo: US Navy

A war weary USS Shangri-La edges into San Pedro Bay to tie up at Los Angeles, California at the end of October 1945. On her deck, her air group’s aircraft are smartly ranged and most of her 1,773 men crew are forming up to spell out the word ALOHA, an appropriate greeting from a ship and her Task Force 38 recently back from the Pacific War. This photo was carried in newspapers across the country. Photo via PicstoPin.

Of all the images of the days aboard Shangri-La in her deployments during the Second World War, this is my favourite by far, and Shangri-La is nowhere in sight. Here, after the Shang returned to Washington via Puget Sound and docked at Bremerton, a group of sailors from her crew gathered at a ski resort near Snoqualmie Pass for some joyous R&R, happy to be home, to be safe, to be in America. The date is just three days before Christmas 1945. Here the group gathers for a wonderful shot in the snowy landscape with relief and peace written all over their faces. Wade Litzinger is centre in this photograph (7th from left, back row), smiling broadly. Looking at this image one sees a tie-in to the image far above of the survivors of the Lost Horizon crash as they gaze upon Shangri-La for the first time. There is not doubt that, for Litzinger and his mates, they have found the true Shangri-La, a long life and happiness... home in America. Photo via Wade Litzinger and Randy Litzinger

One of Shangri-La’s postwar missions was to carry aircraft to be guinea pigs for the Operation Crossroads atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific. Here in 1946, we see her transiting Lake Gatun midway through the Panama Canal system, loaded with war surplus fighters destined for destruction in the tests. Image via warbirdinformationexchange.org

The flight deck of USS Shangri-La after the Second World War (1947—the Western Pacific) with aircraft ranged forward of the barrier and all hands focusing on a Curtiss Helldiver of attack squadron VA-5A. The aft 4-inch gun turrets are trained to starboard, possibly standard operating procedure when recovering and launching aircraft to keep the barrels from damage. Tracing its origins to 1928, VA-5A operated under the designations Scouting Squadron Three (VS-3) and Bombing Squadron Five (VB-5) during the Second World War, participating in the Battle of Eastern Solomons and raids on the Marshall Islands and Truk. Designated VA-5A in 1946, the squadron became VA-54 in 1948. It was the last fleet squadron to operate the SB2C Helldiver. During 1947, the squadron completed a Western Pacific cruise aboard USS Shangri-La (CV-38), being assigned to Carrier Air Group Five (CVAG-5). Photo: US Navy

In 1955, just weeks after her massive refit at the Puget Sound Naval Ship Yard in Washington, USS Shangri-La paid a visit to San Francisco en route to San Diego. While passing under the Golden Gate Bridge, her crew spelled out the words “HELLO BAY AREA” for the assembled photographers. She docked at Naval Air Station Alameda on the Oakland side of the bay. During her refit, she received the first structurally angled flight deck in the US Navy, as well as other improvements, which made her, for the moment, the most modern carrier in the fleet, if not the world. UP Telephoto via Utah Daily Herald

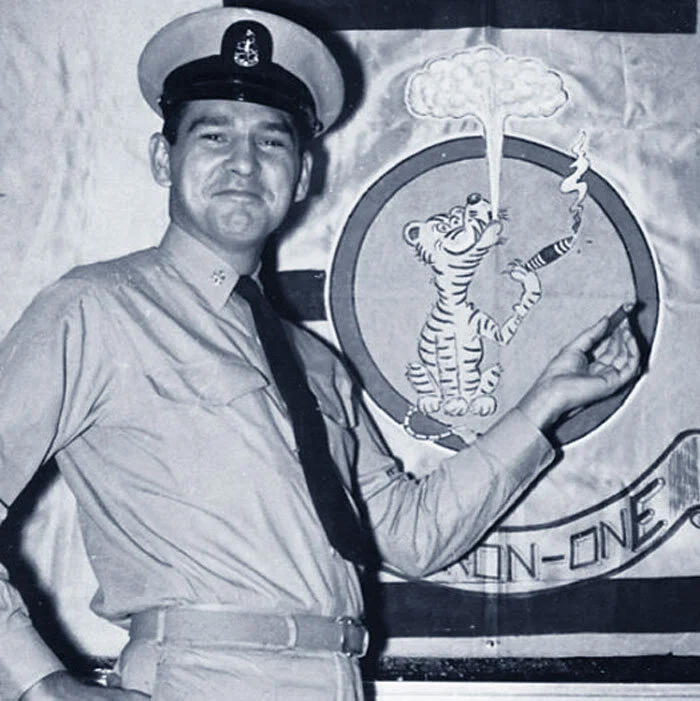

Within ten years of her launch, USS Shangri-La was fully in the jet age, with a newly acquired angled deck (we can just make it out at the far right bottom) and steam catapults. Here A US Navy McDonnell F3H-2 Demon of Fighter Squadron VF-124 Gunfighters and a Douglas A3D-1 Skywarrior are taking part in carrier qualifications in 1956. Behind them are ranged a pair of McDonnell F2H Banshees and a Piasecki HUP-2 of HU-1 twin rotor helicopter. A very close look at the dark blue Skywarrior on the port cat reveals, beneath the cockpit, the famous “Smokin’ Tiger” crest/patch of VAH-1, the first operational Heavy Attack squadron with the A3D, based at the time at Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida. A close-up of the crest is in the following image. Photo: US Navy from USS Shangri-La Cruisebook 1956–57

On the occasion of his promotion, Chief Petty Officer Kenneth Raymond Mueller takes a proud drag on a Smokin’ Tiger cigar in front of the squadron emblem, also displayed on the side of an A3D in the previous photograph aboard USS Shangri-La. That same decal was proudly displayed and preserved on the left rear window of the Mueller family 1960 red Plymouth Valiant until disposed of in 1972. Photo via Michael Mueller

Whale watching. An A3D-1 Skywarrior is catapulted from USS Shangri-La in the late 1950s. Nicknamed the “Whale” for its enormous size and weight, the A-3 was the heaviest aircraft to launch from Shangri-La, double the weight of the B-25 Mitchell of Lt. Commander Bottomly. Four A3D-1s were loaded aboard Shangri-La in late August 1956 to promote the airplane’s capability. Two, probably assigned to VAH-2, were launched on 1 September off Mexico for a flyby at the Oklahoma City Air Show and return to NAS North Island. The other two, probably VAH-1’s, were launched off the Oregon coast on 2 September for a flyby at Oklahoma City and a subsequent landing at NAS Jacksonville. Photo: US Navy

It’s always nice for us Canucks to bring the story somehow back to Canada, since our espoused goal is to tell the story of Canada’s aviation heritage. Here, if you can get past the beautiful woman in the foreground, USS Shangri-La is towed to dockside on the St. Lawrence River at Québec City in 1963. Shangri-La was visiting with other ships including the heavy cruiser USS Newport News. One of our Vintage Wings members, Daniel Duclos, is the young boy in the arms of his mother, young Mme Duclos. Photo: André Duclos – Courtesy Daniel Duclos

The Shang’s sailors line the deck and rails as she is brought up to the riverside dock at Québec City in 1963. You can bet these young sailors were keen for shore leave in the lovely French city of Québec, with its beautiful architecture and, well... beautiful women. Photo: André Duclos – Courtesy Daniel Duclos

As soon as Shangri-La tied up at Québec, her crew unfurled a banner welcoming guests aboard... in French. Now, that’s class. Photo: André Duclos – Courtesy Daniel Duclos

Two U.S. Navy Douglas A-4B Skyhawk attack aircraft (nicknamed Scooters or Heinemann’s Hotrods for their designer) from Anti-Submarine Fighter Squadron 1 Warhawks in flight with USS Shangri-La steaming off to the right below. VSF-1 was assigned to Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8) aboard Shangri-La for a deployment to the Mediterranean Sea from 29 September 1966 to 20 May 1967. A carrier-based Skyhawk was the aircraft Senator John McCain was flying when he was shot down over Vietnam. His father, Vice-Admiral John McCain made Shangri-La his flagship in May of 1945. In 1970, Shangri-La returned to the South Pacific to launch attacks against North Vietnam. She was decommissioned in 1971 and placed in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet and berthed at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. There she remained on reserve for the next 11 years.

The US Navy aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La (CVS-38) cruises toward Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, on 11 February 1970. Shangri-La was working up for her last deployment before her decommissioning. Her last cruise, with assigned Carrier Air Wing 8 (CVW-8), was to Vietnam and the Western Pacific from 5 March to 17 December 1970. Although nominally re-designated as an anti-submarine carrier (CVS) on 30 June 1969, the Shang still operated as an attack carrier (CVA). Text and photo via Wikipedia

![“Bomb Tokyo with Your Extra Change!” In 1942, Roosevelt’s Shangri-La witticism was well known and well appreciated in America, enough to inspire the name of the ship and even a war bond and stamp drive to raise funds to build the carrier to avenge the loss of the Hornet. According to an article in the St. Petersburg Times of 31 July 1943, the local community’s goal in the drive was $60,000.00, with the national goal being $131,669,275.00 and Florida’s portion being $1,397,414.00. The article also stated that “War stamps purchased in July all over the nation will go to pay for the carrier, to replace the Hornet from whose deck went Jimmy Doolittle and his men to bomb Tokio [sic]. The Hornet was later sunk. The new carrier’s real name will never be known until after successful action at sea. Until then, it will be the “Shangri’La,” bought and paid for by public contributions.” This is the first and only place I had read that the name Shangri-La was supposed to be a temporary one. One wonders if this was true, or even what people thought was true back then.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1628297039568-MGBKT4CBW1JVPPGDTPJR/6A81D4E2-1F67-4B9B-952A-460927A92388.jpeg)