THE BOYS OF STE. ANNE’S

This is not a story about the terrifying night raids that Bomber Command aircrews willingly went on, or about the terrible toll they paid. This is not a story about great aces and great battles. This is not a story about the sacrifices made by those men and women who put off their futures and laid down their very lives and the 25,000 beautiful sunrises that they were due. Nor is this a story of the discipline, courage, loneliness, deprivation, risks and terrors that were the daily lives of everyone who put on a uniform during the Second World War and did their duty. This is a story about what we still owe them 70 years after they came home. This is a story about dignity. Theirs... and ours. It’s universal. It matters not that you are Australian or American or British. It matters that you understand the debt owed and paying down the balance.

When I was a young boy, I lived in a neighbourhood on the outermost edge of a post-Second World War baby boom growth spurt. The stolid houses of the idyllically named Elmvale Acres were just beginning to seem like they had been there for a while. In my first year of high school, I was aged 12 and enrolled in an all-boys Catholic school along the Rideau River, about two miles from my parents’ home. In spring and fall, I rode my bicycle the two miles to school, down recently paved Smyth Road and always into a cold early morning head wind.

About three quarters of the way there, on my right hand side, I would cycle by a group of wood frame structures scattered seemingly randomly on a large grassy property—well manicured and trim. The buildings were one storey, light grey clap-board bungalows with wooden ramps that sloped to the ground at either end, wooden boardwalks that connected building to building. There was a couple of larger structures, a small parking lot and a red brick building housing a swimming pool, with tall white framed, multi-paned windows that were always fogged up.

As I cranked and puffed my way on my rickety old bike past the shady property on a sunny morning or warm afternoon, I could see, on almost every fine day, and even some dark and rainy ones, a number of lone men, resting in wheelchairs on porches and patios. Sometimes they would be accompanied by a nurse in crisp white uniform. Rarely were they in pairs or groups. These men were the lonely wreckage of three wars—the First and Second World Wars and Korea. The older ones, probably in their 60s, were veterans of the Great War, while the ones my father’s age were veterans of the Second World War and Korea. Some were burned. Some sat in silence in wheel chairs, legless or armless, or both. They smoked and stared into the dappled light of an afternoon or early morning as if looking across time, a void that separated them from me and my wheezing passage past their home. The scene was idyllic, the leaves rustling, the grass rippling, but the feeling I got was of some great, quiet sadness and a sense that these men, though kindly treated, were being kept from upsetting society.

I was a twelve year old boy and my shyness and fear of the unknown kept me from turning my bike towards them and saying hello. The most I ever did was wave at them as I pedalled by, once realizing with dread that the man I waved at could not return the salute. I wish now that I had managed the courage to introduce myself; that I had sat with them for a few minutes each day; that I had been kind to them, made them laugh, brought them something, listened to their stories, told them mine, made them feel relevant and empowered, showed them love. But I did not.

To this very day, I regret this. Ashamed might be too harsh a word, but it’s close to what I feel. Perhaps that is why I try so hard to know them today.

Recently, along with Vintage Wings photographer Peter Handley and fellow volunteer Claude Brunette, I visited a place where all those things I didn’t do so long ago were happening to a rapidly diminishing demographic of Second World War and Korean War veterans. A place where people are kind to them, make them laugh, listen to their stories, empower them, love them, value them. It is a place that every Canadian should be proud of—Ste. Anne’s Hospital at Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, west of Montréal, Québec.

Ste. Anne’s Hospital is today the last remaining veterans’ hospital administered by Veterans Affairs Canada, the federal department responsible for the well-being of Canada’s military veterans. When it was built in 1917, it was one of nine hospitals established by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Robert Borden and operated under the Military Hospitals Commission. The country was being overwhelmed by the return of large numbers of wounded, gassed or sick soldiers from the Western Front in France and Belgium, and new facilities were desperately needed as well as new ways to deal with new kinds of injury—shell shock and poison gas.

At the end of the First World War, the military hospital at Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue had its own railway siding (above) where invalided soldiers were off-loaded on stretchers right from the train, which likely was loaded at Halifax. It says much about the number of wounded expected, to have a dedicated rail siding for their efficient delivery. Photo via Ste. Anne’s Hospital

By the Second World War, the multiple wings of Ste. Anne’s Hospital were ivy-covered, and from the outside, seemingly idyllic. Like the Rideau Veteran’s Home I used to pass on my bicycle as a child, the care and therapies provided to long-term veteran residents was, while well-meaning, more primitive than it is today. Photo via Ste. Anne’s Hospital

On the outside, Ste. Anne’s Hospital was friendly and welcoming. On the inside from the outset, the atmosphere was, according to the Veteran’s Affairs website “friendly but disciplined. In 1916, the Military Hospitals Commission imposed military discipline on the institutions under its jurisdiction to improve attendance at trades training programs, and to reduce the risk of bad behaviour by some of the Veterans. Military districts were transformed into Hospital Commissions Command Units, thereby placing staff and patients alike under military authority. Military discipline was the order of the day until Ste. Anne’s Hospital moved to its new premises in 1971.” Photo via Ste. Anne’s Hospital

Ste. Anne’s Hospital around the time of the Second World War. Many Canadian wounded were invalided back home via hospital ship and then train to this facility. Photo via Ste. Anne’s Hospital

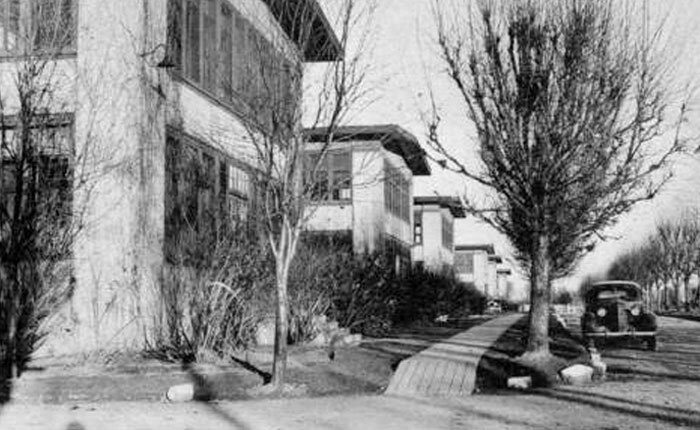

A photo of Ste. Anne’s Hospital during the same period as the previous photograph shows that, as far back as the Second World War, accessibility was important as witnessed by the ramped sidewalks. One of Vintage News subscribers, Sandy Sanders, had this to say about his memories of Ste. Anne’s Hospital in these days, and it says a lot about the science of dealing with veterans in those days before the Second World War: I went to Macdonald High School in Ste. Anne’s from 1939 and remember the hospital very well. We used to see patients walking around Ste. Anne’s and they were dressed in Blue or Grey clothing. My memory fails here because one of those colours was not assigned to regular patients. One color was not to be served alcohol in any of the local watering holes at all. Some of those had a red circle or cross painted on the back of the shirt area. One of those so marked were not supposed to be able to leave the hospital grounds. Photo via Ste. Anne’s Hospital

A brand new and modern facility was built in 1971. Recently however, it was completely overhauled, changing older open concept wards into wards of all private rooms. Photo via MemorableMontreal.com

At the end of the summer, Peter, Claude and I met at the Vintage Wings hangar, piled into my car, loaded up on Tim Hortons coffee and donuts, and headed down Autoroute 50, jumped the Ottawa River at Hawkesbury and flew on towards the Québec border, crossing Lac des Deux Montagnes. As soon as you cross the bridge into Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, you cannot miss the hospital. I have seen it every time I have driven to Montréal since 1971 and I always wondered what the grey, monolithic and imposing building was. I would never have guessed it was a place where our heroes are cared for.

Our goal was to find out how our aging veterans were faring, see how they are cared for in their final years. I had been speaking beforehand with Andrée-Anne Desforges of the hospital’s foundation and asked that we might meet a few of the residents, in particular those who once belonged to the Royal Canadian Air Force. We were to meet Andrée-Anne in the offices of Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation. In the first decades of the hospital’s existence, the outside of the building was neat and trim, surrounded by gardens, idyllic. But on the inside, discipline was military, medical science dealing with physical and psychiatric combat injury was just developing. Today, the building is formidable, even ugly, but on the inside, the environment is supportive, encouraging, sunny and meaningful. The care of aging veterans with mobility and memory issues has come a long way and the facility is today not so much a hospital as it is an embracing community.

Ste. Anne’s Hospital serves veterans in two groups—called Traditional Veterans and New Generation Veterans. The former group includes aging veterans of the Second World War and Korean War, most of whom are permanent residents of the facility with long-term health issues, mobility requirements and cognitive deficits. The latter category is largely comprised of younger veterans of Canadian combat or peacekeeping missions in places like Kosovo, Bosnia and Afghanistan. Today, the need for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment in Canada is high following Canada’s 13-year involvement in Afghanistan, where more than 40,000 Canadians served. New generation veterans come from Québec and across Canada to receive specialized services for PTSD and other operational stress injuries. Ste. Anne’s has become a world leader in the treatment of PTSD, employing an interdisciplinary team approach, bringing together psychiatrists, psychologists, physicians, social workers, nurses and other professionals. It serves the Canadian military community through two outpatient clinics (Stress Injuries and Pain Management) and a residential clinic.

Ste Anne’s Hospital is now associated with one of Canada’s leading medical programs—Montréal’s McGill University Faculty of Medicine. Through this association the hospital is set to become a university learning centre and a potential centre for professional development for students and young graduates, through clinical internships in expertise areas such as the treatment of PTSD.

Ste. Anne’s Hospital with its new Remembrance Pavilion at left. Photo via MemorableMontreal.com

The people we had asked to meet and speak to, however, are from the former group—the “traditional” veterans. Being an organization that works to teach the oft-forgotten lessons of duty, honour and sacrifice to the youth of today through real-life stories of the airmen of the Second World War and Cold War, we wanted to see how these great Canadians, to whom we are so greatly indebted, are being treated in the last remaining military hospital still tasked with their well-being. The interviews, questions, photographs taken and time spent on our visit were largely with these men and women, the oldest of our veterans. This is not to diminish in any way the broad healthcare objectives of the whole facility and the world-leading position of the hospital with regard to military service stress injuries, but rather to take a look at the care being provided the traditional veterans whose stories now populate our Vintage Wings website.

While the PTSD research conducted and clinical therapies offered new generation veterans are indeed changing the stress injury landscape, so too is the clinical, social, occupational and scientific work conducted and applied to the lives of Ste. Anne’s geriatric or cognitively deficient residents. Ste Anne’s Hospital is now associated with one of Canada’s leading medical programs—Montréal’s McGill University Faculty of Medicine. Through this association the hospital is set to become a university learning centre and a potential centre for professional development for students and young graduates, through clinical internships in expertise areas such as the treatment of PTSD. In simple words, this means that the traditional veterans at Ste. Anne’s are living well and benefitting from an ever-expanding array of therapies, simple social programs, time-tested techniques and scientific breakthroughs. Much of the success of Ste Anne’s, however, is due to the people who work on the wards and with the Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation. Their respect for the men and women in their care is the very foundation of their work and their motivation to search for constant innovation. Andrée-Anne Desforges spoke warmly of the veterans at Ste. Anne’s, the people whose lives her foundation works so hard to improve and make easier. With a broad warm smile, she spoke of the small group of veterans assembled for us as “The Boys”, an endearment which demonstrated to Claude, Peter and myself that these men are not simply patients, but are, for the staff, still men with youthful spirits, a desire for meaning and perhaps with just a bit of the devil still hiding inside... after all, they are air force.

Ste Anne’s Hospital Foundation development coordinator Andrée-Anne Desforges and ward nurse Marc Lessard visit veteran Monsieur Rosaire Gaston Ouellette in his room. Each veteran is encouraged to hang pictures and bring in mementos to make the rooms their own. Photo: Peter Handley

Long-term residents settle in and make their rooms an individual statement, surrounding themselves with memories and personal items that provide comfort. In this way, residents turn their hospital rooms into their homes. The pole on the right of the bed provides support, allowing aging veterans to better rise safely from their beds. Photo: Peter Handley

In the wards caring for the traditional veterans, all residents are in long-term care. Some of these veterans entered the hospital many years ago and will end their lives here, surrounded and supported by people who care. The average age of the more than 350 traditional veterans at the hospital, including those from the Korean War, is 92 years. When war veterans reach this age, they are facing the same health issues that are found in the general geriatric population—dysphagia, mobility, pain management, geriatric dental issues and palliative requirements. What tie these people together, however, are their war experiences and our duty to look after them, even though most are not suffering from the effects of their military service.

From necessity, the hospital works with or has developed new ways to manage pain and treat operational stress injuries in new generation veterans and to treat dementia and difficult medical problems like dysphagia in traditional veterans. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, can affect anyone, but it is prevalent in much older populations (it affects up to 70% of institutionalized seniors and approximately 10% of people over 65) and is often combined with or is related to other wider problems such as a stroke. Food, for many dysphagia sufferers, is puréed to make it easier to swallow, whether it is meat, vegetables or other dishes. When in this form, food becomes unappetizing to those whose appetites are already diminished. Something as simple a reforming the puréed food to resemble its original shape can transform a meal for a dysphagia patient. Using culinary purée forms and thickeners, a plate of puréed beef, potatoes, peas and carrots can still look as it should—a simple way to make a large psychological difference to a veteran. The expertise gained and technology developed at Ste. Anne’s Hospital resulted in a technology transfer in 2000 to a spin-off company called Prophagia which produces food products for dysphagia sufferers.

For patients with dysphagia, swallowing food is difficult enough, but liquefied and puréed foods become unappetizing. However, simply reforming the puréed components of this meal (ham, pineapple, asparagus and beets) in their original shape has profoundly positive psychological effects on veterans who have to deal with the problem. Photo: Prophagia

Along with Montréal’s McGill University Faculty of Dentistry, Ste. Anne’s Hospital is developing new science, treatments and services related to geriatric dentistry. The dental health of aging veterans can be affected by medications, diet, cognitive problems and even weight loss. Our veterans all come from a time before fluoride and widespread access to quality dental care, and dentures, bridges and other prosthetic oral devices are the norm. Weight loss can result in ill-fitting dentures and discomfort that can affect quality of life. Anyone with fit or other problems can simply visit the in-hospital clinic for a quick adjustment.

Providing a happy, varied and worthwhile life for our traditional veterans necessitates being at the forefront of geriatric, psychiatric and palliative science, but it also involves a whole lot of small things. Things that demonstrate love and caring. This is what the Hospital and its Foundation does so very well. Residents are encouraged to socialize, move about the facility and take part in a wide variety of activities and events. Volunteer pianists accompany veterans in rousing sing-along sessions twice a week in the gymnasium. There is a two-lane bowling alley that was particularly busy when we were there and the ground floor resounded with the rumble of bowling balls and the clatter of tumbling pins. Residents can work on crafts, art and woodworking projects to keep them busy and active. This also serves to demonstrate to the veterans that they can still create objects of value, that there are still things to learn.

Ste. Anne’s Hospital has many aging veterans whose health issues mean they will likely spend the rest of their lives as residents. The hospital looks after their well-being in many ways beyond ordinary therapeutics. The woodworking shop is a favourite with the male veterans, many of whom require the assistance of Pierre Groulx, the workshop’s technician who helps them with dangerous power tools and offers a second set of hands. The veterans work on small projects such as wooden toys for their great grandchildren and Groulx says it’s not a miracle cure or anything, but it helps veterans deal with the stresses of a changed life and the loneliness that comes with the loss of wives and most of their friends. Photo: Peter Handley

The workshop is equipped with many tools from large power tools to traditional brace and bit. Photo: Peter Handley

Anthony Ozanick, a quiet and elegant RCAF veteran, was a ground crew mechanic with 408 “Goose” Squadron. He served with 6 Group at RAF Linton-on-Ouse. Today, he finds relaxation and companionship in the woodworking shop. Photo: Peter Handley

Anthony Ozanick flew operations in Avro Lancasters from the big Bomber Command base at RAF Linton-on-Ouse, one of 11 stations allotted to 6 Group, RCAF. It is still today one of the busiest of the RAF’s airfields, used for fast jet pilot training. Photo: RAF

Many male residents love to hang out in the woodworking shop with Pierre Groulx, making doll houses for great grandchildren or birdhouses as gifts for visiting relatives. Photo: Peter Handley

An arts and crafts studio with abundant natural and overhead light provides a popular place for residents to while away the day in creative pursuits ranging from oil painting to weaving to doll and toy making. Here, art advisor Diane Martineau helps a resident at one of the many tabletop looms in the studio. Photo: Peter Handley

Mme Lacasse, one of about 30 female residents at Ste. Anne’s Hospital, weaves place mats and table runners, projects which are popular gift items for family and friends. Photo: Peter Handley

Mme Hélène Lacasse slides the loom’s shuttle drawing weft threads through the warp. Working on such devices as looms, residents keep their minds active and creative and their coordination sharp. An afternoon with a friend at the looms provides a strong social experience as well as resulting in creative work. Photo: Peter Handley

The art studio is lined with all sorts of finished projects (stuffed animals, birdhouses, pottery, picture frames), all of which are for sale at extraordinarily low prices. The profit from the sale of any of these items is given directly to the veteran who created it. Photo: Peter Handley

Colourful snakes made from felt adorn the arts and craft studio. Simple, repetitive arts projects like weaving and toy making provide mental stimulation, social intercourse, artistic outlet and the simple satisfaction of creating something. Photo: Peter Handley

While interviewing the staff and veterans at the arts and crafts studio at the hospital, I found that one could purchase any item on display (and there were many), and the profits from the sale would go directly to the veteran who made that item. While this may not mean a lot in terms of money, it certainly would provide warm confirmation that their work was appreciated and yes, valued. I bought two white stuffed lambs for my granddaughter and was able to give them to her the following week. The look on her face tells it all. I also sent this image to the Foundation and they showed it to the veteran who had made the two lambs... it’s always good to close a circle. Photo: Dave O’Malley

Social activities are an important part of everyone’s life. Sharing meals, playing cards or billiards, shooting the breeze over a cold beer at a pub night, and that golden-age standard, Bingo—these are all organized for the veterans in the care of the hospital to build back into their lives a sense of normalcy and camaraderie. When local corn-on-the-cob or strawberries are in season, events are organized and residents get together to celebrate and share food surrounded by a warm community. One very effective program funded by the Foundation and delivered by hospital volunteers is called the Skype Project. Volunteers bring laptops with them when they visit veterans who sign up for it. The volunteers can then connect the veteran to family or friends in far-off places. Veterans who, by virtue of their age, are not familiar with modern computer technology, can now see and talk to their children, grandchildren, great grandchildren and even old comrades through a Skype connection, right in their rooms.

The Foundation assesses any new idea to make life better for these deserving men and women, always looking for simple, cost-effective ways to keep residents engaged. Music and zoo therapies are favourite and effective ways to replace parts of people’s lives they have left behind. The power of an animal to bring joy and comfort is undeniable, and live music soothes the stresses of loneliness. And, of course, laughter is the best medicine—in a program called La Belle Visite, therapeutic artists pay visits to veterans in teams of two, encouraging reminiscence, giving a place for humour, inviting relational sharing and socialization, stimulating the imagination and improving the mood of patients who face dark moments.

Ste. Anne’s Hospital staff go the extra mile to customize mobility and accessibility devices such as wheelchairs, walkers, canes and others to fit each resident. This ensures the highest degree of comfort and utility, and demonstrates to the veterans that they are considered unique and important. Mobility workshop technician Tony Pednault is much loved and respected for his creative modifications to mobility devices that provide maximum comfort and utility, all customized to the requirements of each resident. These requirements are of course constantly changing, so residents often drop by for an adjustment. Fellow Foundation staff tell me that he can, and will, do just about anything for one of his residents. Photo: Peter Handley

Stacks of wheelchair cushions. The Hospital and its Foundation supply all the devices and activities that make life at the hospital a positive experience for aging veterans. Storage rooms are packed with all sorts of chairs, cushions, attachments and technical aids that can be combined to increase comfort and mobility for men and women in their final years. Photo: Peter Handley

Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation understands that many of our Second World War veterans grew up and remained deeply religious, finding solace in the spiritual community of their choice. Here we see two simple but effective details in the hospital chapel that speak to the constant concern for the well-being of the minds and hearts of veterans. The chapel is a multi-denominational chapel, easily converted to contain services of any Religion, be they Jewish or Christian or Islamic. The fourteen Stations of the Cross, found in any Roman Catholic church, are housed in shallow doored alcoves in the walls, which can be closed for events and services in another denomination. Higher on the wall, we see a television camera, which automatically follows the movements of the celebrant in any service. Residents can attend a service in person, or, if their mobility or memory issues prevent them from attending, they can have it broadcast on the television in their hospital room. Photo: Peter Handley

Simple techniques assist healthcare workers to better serve their veterans. Each floor of a wing of the hospital has a dining room for its residents. Place settings are set for each resident and a place mat for that individual tells the story of each resident’s health needs—using icons for specific requirements and food issues. Photo: Peter Handley

Volunteers with Ste. Anne’s Hospital provide residents with a large library of books with titles of great interest to the “Greatest Generation”. The volunteers at Ste. Anne’s Hospital are vital to the quality of life for our veterans. In addition to organizing the library, they organize activities and outings and accompany the veterans who attend. They also make bonds with veterans on palliative care who have no families or have families too distant to pay regular visits. Having a friend visit as they face death is a critical part of the palliative process. Photo: Peter Handley

The new Remembrance Pavilion at Ste. Anne’s Hospital is a residence specially designed for veterans with memory problems. The modern facility was created especially for the issues facing patients with cognitive deficits. For instance, there are no dead-end corridors where a wandering patient might find himself or herself. Instead all corridors allow patients to move freely, yet always bringing them back to the heart of the building. Rooms in the Remembrance Pavilion are sunny with lots of window area. Bedside bulletin boards in each room utilize a system of symbols to tell staff of the specific needs for each resident, similar to the system used in ward dining rooms. Photo: Jean-Guy Lambert de Jean-Guy Lambert Photographie

The Foundation is always in search of therapies and programs which enhance life for residents and their families, especially programs that give high emotional and well-being return on just a small investment. In the Remembrance Pavilion, the hospital volunteers and staff have adopted a unique and powerful idea... one that creates lasting feelings and memories for family members of dementia patients. As loved ones slip away one memory at a time, family members are greatly comforted by the Holding Hands Forever Project. The idea is simple, elegant and deeply emotional: the resident and a loved one clasp hands for a just few minutes with their joined hands immersed in a non-toxic material the consistency of pudding—clasping hands for about five minutes. Then, using the mold which is created, a cast is made in plaster, capturing every wrinkle, fold and even the emotion of the moment. The clasping or holding of hands, either spouses or great grandchildren is a powerful act of affection, one which family members can keep forever. I can only imagine how wonderful it would be to have a cast of the hand of my grandfather, a veteran of the trenches in the First World War. Photo: Peter Handley

Toute personne est une histoire sacrée—“Every person is a sacred story.” reads the artwork at the entrance to the group lounge in the Remembrance Pavilion. Many of the veterans who live here have forgotten their stories, but the love and respect shown them by the hospital staff grants dignity for the ending of their story. The handmade decorations which line the walls of the Pavilion are created by a volunteer who changes them up frequently and seasonably. Photo: Peter Handley

Each week, a piano player will visit Ste. Anne’s Hospital and play the old songs these aging warriors sung when they were young men and women. There are usually two singalong sessions—one in the main hospital tower and one in the Remembrance Pavilion. The songbook includes the lyrics for hundreds of songs for both French and English veterans. Singing was once the only entertainment for young airmen in faraway places, fighting for their lives. In those war years, messes from Scotland to Ceylon rang with songs of longing, love and hope and yes, bawdiness. It’s appropriate, as these men and women reach their nineties, that singing brings them the same joy and solace. Photo: Peter Handley

Our trip to Ste Anne’s Hospital was not just to see how our veterans are cared for in the last years of their lives, but to actually meet them. Andrée-Anne set us up with a small number of veterans who were with the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War, and we went from ward to ward, room to room, to spend a few moments with each. At one point, we were introduced to Flight Lieutenant Leonard Allistair Fuller, a full-tour veteran of Bomber Command operations on the Handley Page Halifax. The sun was beaming into his room, his bed was neatly made, his room was sparse but tidy and welcoming. On his bed he had laid out his 415 Squadron RCAF blazer, upon which his rack of service medals gleamed in the sunlight. Fuller popped up from the edge of his bed and welcomed us warmly, then quickly shot across the hall to fetch another chair to accommodate all four of us. He then ran back to invite another RCAF veteran, Sergeant Gilbert Prévost, to join in the conversation and then Everett Paul Firlotte, a Lancaster tail gunner. It was clear from his actions that we were anticipated and that Fuller was happy to see us. We were treated like celebrities. We could only spend about a half-hour in his room, but it was one of the best 30 minutes I have ever spent. Our conversation centred around questions about their service during the Second World War. I knew that by answering these questions about their lives so long ago, I could gauge their personal well-being, their willingness to still engage life. The first thing I noticed was how well they were turned out—clothes were cleaned and pressed and their personal hygiene was impeccable. Together, seven of us relaxed in Fuller’s room and wandered back over time. Their animated faces showed that our questions were bringing up memories, both happy and sad.

It sucks to be getting old... I can tell you that from personal experience. In all our interviews this day, it was at times difficult for the men to recall all the answers to our specific questions—about bases served on, places where they were trained and squadrons they served with. We could sense the frustration as they searched their memories for answers, but they never dwelled on this, choosing to remain engaged and animated. This was a good day. The sun was shining. People were visiting. New friends were made. There was laughter and moments of reflection. Above all else this day, I felt an overriding sense of dignity that surrounded the place—a sense that each resident felt valued, was surrounded by love and support, that each day was, like today, a good day... or at least the best possible day.

Dignity... who could ask for anything more?

The Visits.

No welcome at Ste. Anne’s was warmer than that of Flight Lieutenant (Ret’d) Leonard Allistair Fuller, a Bomb Aimer who completed a full tour on Handley Page Halifax bombers with 415 Squadron. Each veteran that the Vintage Wings team interviewed this day had been asked ahead of time if we could speak to them. That morning, we ran into Fuller in the hospital’s physiotherapy gym, where he said, with a twinkle in his eye: “I’ll be seeing you later.” When later that day we visited him in his room he crossed the hall to invite other airmen to come in for a bit of old time hangar flying and to get some chairs to handle all four of us. It was clear that our visit was a highlight and that these veterans would love the chance to speak about their experiences. Photo: Peter Handley

The Boys of Ste. Anne’s Hospital, Flight Lieutenant (Ret’d) Leonard Fuller (left) and Sergeant (Ret’d) Gilbert Prévost (right), host Vintage Wings volunteers Claude Brunette, Dave O’Malley and Peter Handley for a wonderful afternoon’s hangar flying. With the sun pouring in on a late summer morning, the Vintage Wings visitors were delighted by the warm welcome provided by the Second World War airmen. Photo: Peter Handley

Gilbert Prévost relaxes in a wheelchair, answering the many questions of the author (left), while fellow airman, Everett-Paul Firlotte, a Rear Gunner on Lancasters, joins in the discussion. Photo: Peter Handley

Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation was created in 1998 to find new ways to continue the support and provision of programs that provide that life affirming dignity for our veterans of the Second World War, Korean War and New Generation veterans. The foundation’s own mission statement clearly states that this responsibility lies not only with the government but with all of us who benefit from the world they have risked their lives to provide us: It is our duty, as citizens, to express our gratitude in a tangible manner—this type of gesture should not only be made by other Veterans and military personnel, family members and Government. We must acknowledge the enormous sacrifices made by Veterans in times of war, as well as those presently being made by our young Canadian military personnel who continue to risk their lives in order to maintain peace throughout the world.

One of the most important programs of Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation, Operation Dignity, is at the very core of what the hospital does. This program seeks to raise $2,500,000 to maintain the level of care at Ste. Anne’s for our Traditional and New Generation Veterans as well as serving military personnel, stating: “Considering that the next few years represent the last chapter in the lives of our Second World War and Korean War veterans, we are determined to offer them the best care and the comfort that will enable them to live and die with the dignity they deserve. With an average age well over 90 years old, our traditional Veterans require more and more advanced care and services related to their physical and psycho-geriatric conditions. ...Furthermore, with advancing age, increasing disabilities and loss of autonomy, they require additional clinical services and innovative programs that also serve to counteract the effects of loneliness and isolation. In this context, the Foundation is increasingly called upon to participate in the well-being of these men and women. ...With the rapid decline of their physical and psychological health, an increasing number of Second World War and Korean War are in the final phase of life and require specialized end-of-life and palliative care. The finding of adapted programs and equipment as well as innovative approaches allows us to properly respond to the personalized clinical and emotional needs on the Veterans and their loved ones.”

As I write this, the Canadian Parliament Buildings are under attack not 100 metres from my office. A soldier standing honour guard at our National War Memorial has been gunned down, possibly by a radicalized homegrown terrorist. The soldier, a reservist with the Hamilton Argyles, was just pronounced dead. All around our offices there is stress and chaos. First responders are everywhere. Far to the west, in Alberta, more Canadians are getting ready to deploy their CF18 Hornet fighter jets to fight ISIS in Northern Iraq and Syria. Other Canadian advisors are soon to be on the ground in Iraq. It is clear to me that veterans of foreign wars are not a thing of the past. The manner in which we treat our veterans is an indication of our real commitment to maintain the freedoms they have fought for. Today, more than any other day in recent memory, it is clear that we will continue to create new veterans, that others will be called upon to defend the way we live, the freedoms we take for granted. It is crucial that they know that we will value their commitment to our country, now, and in all the years we pray they will be able to enjoy.

If you wish to demonstrate your commitment to the support of our aging veterans, new generation veterans and serving military personnel, to the continuation of their dignity and quality of life, no matter how short, and to that of future veterans, I recommend you make a donation to Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation under the Operation Dignity project by clicking on this link.

Dave O’Malley

Vintage Wings of Canada would like to thank Ste. Anne’s Hospital Foundation, in particular Andrée-Anne Desforges. As well we appreciate the time shared with Leonard Fuller, Gilbert Prévost, Everett Paul Firlotte, William Myers, Germain Beaulac, Hélène Lacasse, Anthony Ozanick and Rosaire Gaston Ouellette. I would also like to thank my companions for the day, Claude Brunette and Peter Handley.