TRIUMPH OVER TYRANNY

In the early spring of 1942, the fatigued and despondent citizens of Paris, the City of Lights, did not see much light on the horizon to brighten their days or their futures. The sidewalk cafés were crowded with German officers and soldiers, the theaters smelled of German tobacco, and the grand avenues and boulevards were draped in the red and black banners of a smug and haughty conqueror in the disguise of an ally. To assist military oppression, many street signs were in German, with French secondary. While gas-rationed Parisians moved about in sad homemade hand- and pedal-operated carts, the Germans cruised the Champs-Élysées in big Daimlers and Mercedes. As if all this evidence that Parisians were not the masters in their own world wasn’t enough, there was one daily humiliation that they had to endure with gritted teeth and burning shame.

Each day, just after noon, while thin Parisians were sitting, warming their wan faces on the terraces and at the banks of wooden restaurant chairs of the Champs-Élysées, nursing ersatz café-au-laits, knifing their croque-monsieurs and reading the depressing news and Vichy propaganda in the day’s Le Figaro, the Teutonic strains of Preussens Gloria and Alte Kamaraden could be heard coming up the Champs towards the Arc de Triomphe. Up the Champs they came—hobnailed boots thumping, glockenspiels ringing, horses clopping—the long grey lines of Wehrmacht and Waffen SS soldiers led by Hauptfeldwebels with jutting jaws, sitting on big white horses, banners, pennants and streamers flying.

Every day, for months now, the disdainful Germans paraded their dominance over the French, always at fifteen minutes past noon, always up the Champs-Élysées—like a Bavarian cuckoo clock, sounding its taunting call. From the terraces and banks of café chairs, German officers sipped brandy and, from beneath the glossy black brims of their Schirmmutze, scanned the faces of the Parisians over the top of their Berliner Morgenpost. While most Parisians feigned disinterest, many actually could have cared less, so long as their croissants were warm and their coffee hot. But any SS Generalstaboffizier worth his party pin could not help but smell the acid scent of burning hatred in the air or miss the squinting stare of men who, despite their obsequious smiles, looked dangerous to National Socialism.

Up the Champs-Élysées they marched to Place de l’Étoile and the Arc de Triomphe, the French military’s most revered monument, where all of France’s victorious Generals’ names are engraved and where France’s unknown soldier is entombed. It was not meant to be ironic... it was a deliberate, mocking and daily insult, designed to put France’s military in its place. Along the parade route, as goose steps beat the holy French boulevard and soldiers sang, men were watching, hiding anger and plans inside their hearts. Out of this display of superiority, there was one thing that really struck these men as a weakness. Not the grey rows of Waffen SS, or the Kübelwagens and BMW sidecar motorcycles, the trailered 88s, or even the war horses... that was for sure. It was the simple fact that the Germans paraded in front of the people of Paris at the same place and at the same time every day. Something should be done about that!

Some of these angry, quiet men were in fact secret agents and, in early spring of 1942, they made contact with Major Ben Cowburn of England’s Special Operations Executive and told them of the regularity of the parade. Originally, the Air Ministry thought this might be a job for Fighter Command’s night fighters (their Spitfires did not have the range at that time), but it was thought that if the specialized Beaufighter they were recommending was to crash, the Germans might acquire some of Fighter Command’s secret technologies. When the intelligence came to the attention of Air Marshal Philip Joubert de la Ferté, the commander of Coastal Command, he declared that one of his day Beaufighter aircraft could do the job. With the raid left to his discretion, he devised a daring, possibly suicidal, raid which could, IF successful, reap tremendous propaganda rewards and would give the downhearted citizens of Paris, and indeed all France, a massive boost in morale to raise their weary spirits. They would know, by this one act, that the Germans were not in fact superior and that they had friends who would, in time, come to liberate them.

The goal of Operation Squabble was to fly down the Champs-Élysées during a daily parade of German troops firing 20 mm cannon shells all the way. One can only imagine the propaganda coup that would have been had the Beaufighter flown down the Champs-Élysées with guns blazing at thousands of parading Nazis. Photo via LIFE

At about the time that the daily Nazi parade intelligence was being brought to the attention of Joubert, the Americans pulled off a daring surprise raid themselves, demonstrating the morale-building power of such an endeavour. In the middle of April that spring, 16 North American B-25 Mitchells and their attendant crews, led by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle, took off from the United States Navy aircraft carrier Hornet and made a daring daylight raid on the city of Tokyo. There was little hope of doing any substantial strategic damage, but being seen to slap the almighty Japanese in the face was pure gold for those looking to lift the flagging morale of the American people. The Americans had the power of complete surprise on their side as the Japanese knew they had no bombers capable of reaching Japan through the now widespread empire they had built over the past half year. They were not expecting the Americans at all, and when 16 medium bombers showed up out of nowhere, and set fire to a few factories, the loss of face was a far greater result of the raid. The Japanese would, as a result, always keep sufficient defensive resources at home to counter future raids and this benefited the Allies strategically. The details of Doolittle’s raid are well known, but there it is no doubt that it had to provide impetus and inspiration to Joubert and Coastal Command to proceed with their idea of a similar raid.

In the spring of 1942, Coastal Command of the Royal Air Force was in its sixth year of operations, but it had not been an easy six. Since its inception in 1936, it had been commanded by Air Marshal Philip Joubert de la Ferté, who always felt that his Coastal Command was given short shrift by the Air Ministry. Looked upon by the Ministry as a lesser command after Fighter and Bomber Commands, and thought of as a holdover of Naval aviation, one must admit that Joubert had a point. At the beginning of Coastal Command’s Second World War history, its squadrons made do with aircraft that were more suited for lengthy patrolling and anti-submarine work—flying boats, light and medium bombers, and some antiquated aircraft such as the Vickers Vildebeast and Avro Anson. By 1941 and 1942, they were transitioning to more capable attack aircraft like the Bristol Beaufort, Consolidated Liberator, and the highly capable and fearsome Bristol Beaufighter.

The Bristol Beaufighter, sometimes referred to as a fuselage in hot pursuit of a pair of engines, was a magnificently powerful and rugged aircraft, much loved by its pilots and navigators. Unlike the de Havilland Mosquito, which would also play a similar anti-shipping and interdiction role, the Beaufighter could not be called pretty. It had, however, a beauty born of function. This aircraft would be the technology upon which Joubert would hinge his daring and risky plan to disrupt Nazi confidence and a daily parade of haughtiness in Paris.

If Joubert’s Coastal Command, or even Fighter or Bomber Commands for that matter, were to attack in numbers, then their presence would set off Luftwaffe alarms everywhere they flew. This attack did not have to be big to result in huge payoffs. The only way to gain the superiority of surprise against a nation expecting you, was to attack with just one aircraft—an aircraft flown by men capable of flying at thirty to fifty feet all the way; an aircraft with the range to fly from England to Paris and back; an aircraft that carried a specialized and highly trained navigator that could take them to and then up the Champs-Élysées and home again; an aircraft whose crew was trained to strafe at the lowest levels and limit collateral damage. An aircraft called the Bristol Beaufighter.

Related Stories

Click on image

Four Bristol Beaufighters of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 404 Squadron practice formation flying in Scotland. From this photo we can clearly understand why the Beaufighter or “Beau” was referred to as “a fuselage in hot pursuit of two engines”—those engines being Bristol-designed and manufactured Hercules 14 cylinder radials. Photo: Imperial War Museum via Terry Higgins Collection

From this point on, Joubert and Coastal Command took over the operation. They gave it the code name “Operation Squabble” which, when you think about it, was appropriate—a squabble being an argument over something trivial. Joubert looked to 236 Squadron to provide a suitable Beaufighter crew for the mission. Again, 236’s squadron motto was appropriate—Speulati nuntiate—“Having watched, bring word” as the mission would in effect bring word to the citizens of Paris that they were not forgotten. For the operation, Joubert selected pilot Flight Lieutenant Alfred Kitchener “Ken” Gatward and his navigator Flight Sergeant Gilbert Fern, who squadron mates called “George”. This pilot and “looker” team was selected because Gatward had demonstrated aggressive and accurate low-level flying whilst attacking German positions during the recovery of the British Army from Dunkirk.

Gatward, a 27-year-old son of a chief Inspector of police in London, England, was a handsome, light haired officer with a serious look about him. Joubert had Gatward and Fern called to his headquarters to ask them directly: “There’s a special mission coming along, I wonder if you’d be interested? I’m afraid it’s not very safe!” Gatward answered this understatement with: “It sounds alright, sir, but what’s it all about?” To which the Commander in Chief replied, “It’s very difficult to tell you unless we know you are interested.” Immediately, Gatward replied, “Of course I am interested!” Joubert then asked whether Fern was also, and though Gatward said Fern was married and would likely not be interested in this kind of danger, Fern said “Oh yes I am!”

Gatward and Fern’s aircraft for Operation Squabble was reportedly the 236 Squadron Bristol Beaufighter Bristol Mark IC, RAF serial number T4800. Here we see the famous aircraft (Squadron code ND-C) of Coastal Command on the ground at RAF Wattisham, Suffolk. Photo: RAF via the Imperial War Museum

Gatward and Fern’s aircraft for Operation Squabble was reportedly the 236 Squadron Bristol Beaufighter Bristol Mark IC, RAF serial number T4800. Here we see the famous aircraft (Squadron code ND-C) of Coastal Command on the ground at RAF Wattisham, Suffolk. Photo: RAF via the Imperial War Museum

Once Gatward and Fern had agreed to do the operation, Joubert filled them in on the intelligence report, the concept and then told them outright that this mission could only be done when there was sufficient cloud cover above to prevent them being detected by Luftwaffe fighters above. They would fly the entire route in the clouds and then descend near Paris for the attack.

In May of 1942, Gatward and Fern began training for the mission, practicing extreme low level flying and practicing their aim with cannons by attacking a shipwreck in the English Channel. The original plan called for them to run down the Champs-Élysées at the exact time of the parade and strafe the Germans in front of the Parisian citizenry, and then, opportunity and ammunition remaining, to strafe the headquarters of the German High Command occupying the Ministère de la Marine building on the north side of Place de la Concorde, but then Joubert and Coastal Command mission planners added a symbolic and dramatic twist to the operation—one which, in the end, would save the mission. In Portsmouth Harbour, they acquired a large French Tricolour flag which they had cut into two strips, and weighted to allow them to unfurl. These two flags were stowed in the two flare tubes just aft of Fern’s compartment half way down the fuselage. The plan was to drop one on the Arc de Triomphe and the other on the Ministère de la Marine as a symbol of solidarity with the French.

During the first part of June, Gatward and Fern attempted the operation three times, flying from RAF Thorney Island, at that time a Coastal Command air base 7 miles from Portsmouth. They entered Nazi-occupied France with little trouble, but were forced to turn back three times when they ran out of cloud cover along the route. The weather situation over France was getting better as summer progressed and it began to look as though the operation was not going to happen. But Gatward and Fern decided, without official approval, that they could do the mission if they flew on the deck the entire way across the English Channel and northwestern France.

The Beaufighter left RAF Thorney Island at 1129 hours on 12 June and flew at wave top level across the English Channel, crossing the enemy coast just north of the city of Fécamp 29 minutes later. Fern called for a course southeast, roughly following the direction of the serpentine Seine, but to the north, bringing them close to the Luftwaffe bases at Rouen. The single Beaufighter did not get reported or if it did the Luftwaffe did not send anything after it.

While screaming at thirty feet towards Paris, the Beaufighter scared up a flock of French crows, one of which struck the starboard oil cooler. The Hercules’ operating temperature spiked, but they pressed on and eventually some of the remains of the rook fell away to allow the engine to cool enough to continue. At the chosen time, the Beaufighter arrived over the suburbs of Paris, with Gatward and Fern picking up the Eiffel Tower in the hazy distance. Gatward steered a course that would take him close to the Eiffel Tower, which he rounded to the south and then they turned to the northwest and climbed slightly to pick up the other large Parisian landmark... the Arc de Triomphe. Below them as they banked, women and men waved and cheered as they saw the inspiring roundels of the RAF flash in the sunlight.

At this point, Fern readied one of the flare chutes to release the French Tricolour over the Arc de Triomphe. Coming up to the west of the big monument, Gatward reefed it into a turn to bring him in line with the massive monument. Just as he flew over it, Fern opened the flare chute and let fly the French flag. There was no time to stop and admire their handiwork, but as Gatward dove to about 40 feet over the Champs-Élysées and swept down the magnificent boulevard, it was clear that there was no parade to strafe.

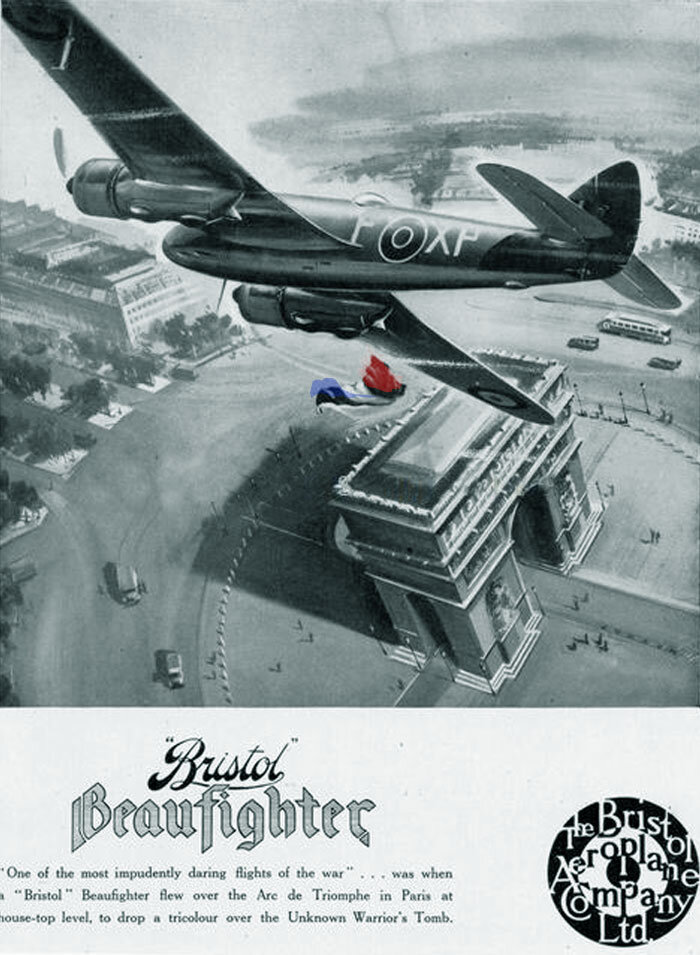

An artist’s impression of Gatward and Fern banking over the Arc de Triomphe and dropping the French flag on the monument was used as part of an advertisement for the Bristol Aeroplane Company Ltd, who I must admit, was in need of a better logo. The Champs-Élysées is the broad boulevard to the left.

I superimposed a photograph of a Bristol Beaufighter on this shot of the Champs-Élysées to demonstrate what it would have looked like from the ground. This photograph was actually shot just four weeks after Gatward and Fern’s legendary flight down Paris’ most storied boulevard. This photograph, taken on Bastille Day, 1942 shows Nazi officers taking in the sun on the Champs-Élysées, ignoring the salutes of enlisted men. One can imagine that the Nazis would be scrambling to get out of the way if they saw and recognized a Beaufighter coming down the “Champs”

There have been a few reasons given for the fact that the Germans were not there, ranging from intelligence agents getting the time wrong to the story that the Germans knew they were coming. It’s hard to believe that the Germans knew they were coming as there was no resistance to the operation at all and as to the fact of the secret agents getting the time wrong, one suspects that this could not be possible given the fact that it was a daily parade.

Regardless of the reasons for the absence of Germans to shoot, Gatward dropped down into the cultural canyon that was the Champs-Élysées, picking up speed as they levelled off below rooftop level. Fern in the back readied the second flag to be dropped over the Ministère de la Marine where the German High Command was about to have a surprise visit, then picked up his heavy F24 reconnaissance camera and snapped a few photographs along the way down the Champs toward the Place de la Concorde. One of those photographs captured the Champs-Élysées entrance to the Grand Palais, Paris’ premier exhibition hall and a rather ironic exhibit sign—La Vie Nouvelle (The New Life).

One of Flight Sergeant George Fern’s amazing photographs taken at extreme low level as he and Gatward rip down the Champs Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe. Armed with a heavy F24 aerial camera, and shooting from the navigator’s blister half way down the fuselage, Fern snapped this shot of the entrance of The Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées exhibition hall and museum. The sign at the entrance reads “LA VIE NOUVELLE” and the irony of a sign saying “The New Life” was not lost on Gatward. In the book Nazi Paris–The History of an Occupation, 1940–1944, there is mention of this exhibit: “For the most part, exhibitions created in Paris during the occupation were dedicated to didactic purposes with the aim of encouraging acceptance of Nazi ideology, as a brief listing —“Le Bolshevisme contre l’Europe,” “La Vie Nouvelle,” “La France Européenne,” “Le Juif et la France”—makes perfectly clear.” In the extreme right we see the Eiffel Tower in the distance. At first I wondered if this was a doctored photo to put the Eiffel Tower into the shot to make it more Parisian for the British or for its eventual publishing in LIFE magazine, but I did a little triangulation in Google Maps, and this angle of the front door of the Grand Palais would indeed include the Eiffel Tower (See map below). Photo: RAF by Flight Sergeant George Fern, DFM.

Now, THIS is an exhibit that Parisians really wanted to see at the Grand Palais. Nearly three years later, American Army armour parades down the Champs-Élysées directly in front of the same entrance to the Grand Palais. Photo via Lenfer Normand

A map showing the flight path of Gatward and Fern’s Beaufighter over Paris that day. Flying in from the west, they lined up on the Eiffel Tower and flew past it to the south, banking hard round it to the northwest and on to the Arc de Triomphe, where they swung round and lined up with the Champs-Élysées. Down the Champs-Élysées they lowered down somewhat to below rooftop level, flying past the Grand Palais museum and exhibit hall. I have not quite been able to determine the exact flight path of the Beaufighter’s turn after the flight down the Champs-Élysées. The yellow dotted path indicates what it would have been if Gatward did not shoot up the Ministère de la Marine immediately, instead turning 270º to the right, which would have given him a good angle on the Ministère coming out of the turn. The image taken by Fern (below) as they flew over the Jardin des Tuileries leads me to think this was their path. Marked here is also the view angle of Sergeant Fern’s camera as they fly by one of the entrances of the Grand Palais museum. Image via Google Map

Place de la Concorde during the Second World War with the Pont de la Concorde crossing the Seine in the foreground. The long portico-faced building facing us is the Ministère de la Marine where the German High Command had their French headquarters. Also we see the Luxor Obelisk rising from the centre of the Place de la Concorde, something Gatward would have to avoid at the height he was flying. Photo from French postcard

Coming down the long slope from the Arc de Triomphe, Gatward and Fern each witnessed Parisians “of both sexes” waving and smiling as they passed overhead. There was no report of Germans diving for cover. One can only imagine the scene, the Beaufighter bumping and bucking on the mechanical turbulence, the sound of the full-throated Hercules engines, the people, apartments, the horse chestnut trees and cafés flashing by, Gatward and Fern’s hearts racing like locomotives. As they closed in on the eastern end of the Champs, they passed the Grand Palais on their right, while on their left the parks gave a fair unobstructed view to the north side of Place de la Concorde, where their secondary target, the German High Command headquarters, was situated. It was at this end of the Champs-Élysées that Gatward did a quick visual check to make sure there were no innocent citizens in front of the Ministère de la Marine before he hosed off a rain of 20mm cannon fire from his four cannons that sent Nazis running for their lives. It is not clear from what I was able to find on the web whether Gatward hosed the German High Command (at an extreme angle) before he made his turn at the Jardin des Tuileries, or, as I suspect, as he was coming out of the 270º hard banking turn (or both).

The confusion lies between the metrics of the next photo, which seem to point to Gatward and Fern being on the same track as when they were coming down the Champs-Élysées (roughly from northwest to southeast at an angle that would have given them a very poor shot at the Ministère) and certain words which were spoken by Gatward himself that lend credence to the possibility he fired before his turn for home. In Lost Voices of the Royal Air Force by Max Arthur, Gatward states: “We swept the length of the Champs-Élysées and hit the target with cannon fire. Then turned round and shoved off for home.” Could he have instead been talking about his turn to the west and home following his exit from Place de la Concorde? If the picture below was taken after the turn, as they were heading toward the Place de la Concorde, the angles would have been different as they lined up on the Ministère. Given the angles of the Tuileries shot, I believe this image was taken after a straight line down the Champs-Élysées and before executing the 270º turn after which I believe they had a better shot at the Ministère de la Marine. If Fern took this photo on the outlet of the 270º turn, then he probably had no time to put the camera down and deal with the dropping of the second flag. Regardless, as they overflew the building on their way home, Fern dropped the second of the two French flags.

At the end of Gatward’s run down the Champs-Élysées, he shot up the Ministère de la Marine which was then being used as German High Command headquarters. Whether he shot up the headquarters before or after his turn is not known by this author, but he hooked round the Jardin des Tuileries to the west of the Louvre, executing a 270º turn, which probably took him over the Seine before heading to the North and then west towards home. There was one other obstacle that Gatward had to keep in view at—the famous Luxor Obelisk which rises 75 feet from Place de la Concorde, just to the left of this photo. It appears they are to the east and to the south of this obstruction. Photo: RAF by Flight Sergeant George Fern, DFM, published in LIFE magazine.

The Jardin des Tuileries today via Google Earth’s 3D feature providing an approximation of the angle flown by Gatward. The Google Earth program cannot be lowered enough to simulate the altitude flown by Gatward. Not much has changed in the intervening years. Image via Google Earth

At 1230 hours, Paris time, it was all over and the two adrenalin-charged airmen were moving as fast as they could out of Paris, flying to the North of the Saint-Lazare train station and spires of Saint-Augustin’s church. From there, Gatward kept it as low as possible, fire-walled the throttles, and following the same route out as he took in, beat feet for home, flying so low and hitting so many flying insects that it became difficult for Gatward to see forward through his windscreen. When they reached the coast just north of the point they entered enemy territory an hour before, Fern gave Gatward a new course for RAF Northolt in London, where they landed 25 minutes later and handed over the 61 photographs that Fern took of the mission.

Beating feet for home, Fern captures their exit to the north of the spires of Église Saint-Augustin de Paris, with the Eiffel Tower off the Beaufighter’s port wing. The long horizontal structure below and to the left of St Augustine’s is likely some of the sheds at the train station at Saint-Lazare. From here, Gatward and Fern headed directly home to RAF Northolt near London. Photo: RAF by Flight Sergeant George Fern, DFM.

Following landing and congratulations by operational planners, Gatward, like many of his peers at that time, made an understated and laconic entry in his logbook: “Paris – No cover – 0 ft (feet). Drop Tricolours on Arc Triomphe [sic] & Ministry Marine [sic]. Shoot up German HQ. Little flak, no E.A. (enemy activity) Bird in STBD (starboard) oil radiator. Returned Northolt and on to Command 61 photos. Heavy rain over England. France fair to light. Northolt to Thorney, Thorney return base. Air Test”. Though it was written up as just another op of many he flew during the war, it was certain that there were not many that had this degree of difficulty and this effect on the war. Photo via Reeman and Dansie auctioneers.

The result of their flight down one of the storied boulevards in the world was not as initially expected. There was no Nazi parade to shoot up and no infliction of violence, except for a symbolic hosing of the front door of the Ministère de la Marine. Two flags were dropped at the planned places, but there is no report what happened to them—though after the fact graphic representations of the event had an enormous French flag draped over the corner of the Arc de Triomphe. Initially, the Germans put out a story that one of their own aircraft had had mechanical trouble and was the one that was flying low over the city, but the Royal Air Force had 61 black and white photographs showing Gatward and Fern’s progress into France, through Paris and on the way home. Within eight weeks, these photos were published in LIFE magazine along with Gatward’s story under the title “British Take a Look at Paris”.

A French illustration depicts a rather fanciful version of the event with a massive French flag perfectly draped over the Arc de Triomphe already in place as a huge Beaufighter (relative to the size of the Arc) flies just inches from the top of the monument.

n the LIFE magazine article, the photo of their exit past Saint-Augustine was published backwards and the church identified as the dome of Les Invalides where Napoléon is buried, but this is wrong and the dome of Saint-Augustine is very distinctive and should never have been confused with that of Les Invalides. The description of the flight in LIFE magazine backs up my theory that Gatward made his turn over the Jardin des Tuileries BEFORE he strafed the front doors of the German High Command’s headquarters. Also according to the magazine article, Gatward dove to line up the shot and was so engrossed in his business of strafing that when he pulled up he cleared the top of the building by less than six feet. The article makes no mention that the original target of the arrogant marching Nazis was not to be found and implies that the main and only mission was to drop the flags and then shoot up the Ministère de la Marine. The French, however, were extremely grateful for the symbolic act which heartened the French people and showed the Résistance that the Allies were listening.

Afterward, Gatward was awarded the first of his two Distinguished Flying Crosses and Fern, as a Non-Commissioned Officer, was Mentioned in Despatches, awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal and given a commission. Fern would rise to the rank of Squadron Leader before war’s end and, after the war, went back to teaching woodworking and arts and crafts. He died in September of 2010 in Bath.

Gatward himself rose to the rank of Wing Commander by war’s end and Group Captain by the end of his RAF reserve career. After the action over Paris, he would be given a rest as the personal assistant of Lt Gen Noel Mason-Macfarlane, the Governor of Gibraltar. He would not return to active duty until the following June, when he was given a flight command job with the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 404 Squadron, a Beaufighter unit engaged in anti-shipping operations in the north of Scotland. When 404’s commanding officer, Wing Commander Chuck Willis, was killed in action, Gatward took command. He relished commanding the exuberant and lively Canadians and together they added to the magnificent history of 404 Squadron.

Remaining in the RAF following the cessation of hostilities, Gatward became the liaison officer with the United States Army Air Force in Germany in 1946. In 1955 he took command of the Royal Air Force base at Odiham and later served with Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe. After serving 30 years in the RAF, he retired on 3 September 1964 with the rank of Group Captain at the Air Cadet Headquarters at White Waltham. He died in 1998 at the age of 84.

It was the recent auction of Gatward’s service medals in late 2012 that brought his and Fern’s compelling story to the fore once more. Colchester auctioneers Reeman Dansie expected the medals would make £8,000, but the collection made more than five times that figure at £41,000. They were being auctioned off as part of the estate of Gatward’s widow Pamela (née Yoemans). Part of the auction included a magnum of Champagne in a presentation case given to Gatward after the war by the government of France in gratitude for his actions that day. It is not known if Fern also received such a gift.

I am happy to report that the bottle was empty.

The group of Gatward’s medals went on sale recently, bringing the Operation Squabble story to the attention of the world once again. The medal group—all official replacements, the originals having been irretrievably lost—comprising DSO dated 1944, DFC with bar dated 1942 on reverse of medal and 1944 on reverse of bar, 1939–45 Star, Atlantic Star, Africa Star, Defence, War Medals and Air Efficiency Award. Photo via Reeman and Dansie auctioneers.

After the war, the French Government presented Gatward (and we assume Fern) with a magnum of Lanson Champagne in a special presentation case with dedication. This case was auctioned off along with Gatward’s medals. The bottle was empty... as it should have been. Photo via Reeman and Dansie auctioneers.

An English newspaper cartoon from the period immediately after the daring mission tells exactly why Operation Squabble was conceived—to provide a morale boost to the citizens of Paris and all of France.

Later in the war, the now Wing Commander Gatward took over command of RCAF’s 404 “Buffalo” Squadron. Here he poses with his personal Beau, as witnessed by the double red stripes in his command pennant on the side of his aircraft, signifying a Wing Commander. All Royal Air Force flags of rank are comprised of red stripes on an “air force blue” background with dark blue borders at the top and bottom. Senior officers have rectangular flags, whereas junior officers’ flags are either swallow-tailed or pennant shaped. Photo via 404Squadron site

Another shot of Gatward, likely taken on the same day as the previous photograph. Note the periscope mirror above the canopy. Photo via 404Squadron site

A very evocative image of Wing Commander Gatward after his return from leading an anti-shipping operation with 404 Squadron RCAF—coffee and cigarette in hand, hair disheveled and oil stains on his battle trousers. This photo was reputedly taken after Gatward’s final op with 404. Note that his tie has been clipped in honour of the occasion and that it’s possible the cup does not contain coffee as he seeks a refill. It is also interesting to note that, back in the day, warriors donned shirt and tie to go to war. Photo via 404Squadron.com

A great and dramatic photo of 404 Squadron RCAF’s Beaufighters attacking a ship. On 12 August 1944 the Sauerland, a heavily armed Sperrbrecher (mine-detector ship), was hit off La Pallice by Beaufighters of 236 Squadron and a detachment from 404 Squadron RCAF. The aircraft flying overhead in this photograph is reportedly that of Wing Commander Ken Gatward, the CO of No. 404 Squadron and one of the RAF’s leading anti-shipping “aces”. Photo: Wikipedia

Lastly, a dramatic and breathtaking painting by famed aviation artist Lucio Perinotto captures Gatward and Fern’s historic flight. For more on this gifted and prolific aviation artist visit lucioperinotto.com. Image via weaponsandwarfare.com

![Following landing and congratulations by operational planners, Gatward, like many of his peers at that time, made an understated and laconic entry in his logbook: “Paris – No cover – 0 ft (feet). Drop Tricolours on Arc Triomphe [sic] & Mini…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/607892d0460d6f7768d704ef/1626741703435-BRTB0JN3NSGIVJKBPH5D/Triomphe09.jpg)