DÉJÀ VU - THE DONALD SCRATCH STORY

In early August 2018, the aviation world was stunned to hear that an employee of Horizon Air, a regional airline of Alaska Air Group, had stolen a large twin-engine, multi-million-dollar Q400 aircraft and spent the next hour joyriding and stunting at low level over the Pacific Northwest Coast near Seattle, Washington, while being shadowed by F-15 fighter aircraft of the Oregon Air National Guard's 142nd Fighter Wing out of Portland. The story, as we all know, ended with the crash and death of 29-year old ramp attendant Richard Russell on sparsely-populated Ketron Island at the south end of Puget Sound. The young man, by all accounts a sweet and respectful guy, opened up to air traffic control in his last moments that he was “just a broken guy” with “a few screws loose”. Listening to young Richard Russell's voice on these tapes, one cannot help but feel an empathy for the man and a compassion for the hidden mental health issues that compelled him to steal an aircraft in his care and fly it with literally zero pilot training. While it was astounding that someone could sneak aboard and start a large and complex twin-engined aircraft, taxi it at one of the busiest airports on the West Coast, take off and fly loops and rolls, it was not, in fact, the first time.

My immediate reaction to this story was not one of shock, but rather one of déjà vu. It was, in many details, similar to the unfortuinate tale of Sergeant Donald Scratch—a decent but troubled fellow who stole a twin-engine aircraft from a West Coast base in 1944; flew dangerously low over populated areas while being chased by fighter aircraft and then crashed into an estuarial island in the Fraser River delta. The only difference was that Donald Scratch was in fact a pilot—and a pretty experienced one at that. What Scratch did on his last flight has been considered, on the one hand, reckless, mad and unbecoming of a pilot in the RCAF and on the other, some of the finest flying ever witnessed. It is a story I have wanted to tell for many years, but have hesitated as some felt that it would be lionizing a criminal, a misfit and selfish person. Even back in 1944, despite a lack of understanding about some mental health issues and an obsession with regulations, RCAF authorities could not help but admire (in writing) Scratch's illegal flying displays (there were two). Some people feel that while he may have destroyed government property, he did not hurt anyone, while others have said it was just luck that no one else was killed. In truth, the men who had to collect his remains such as they were from the spot where he ended his life were most certainly affected for life.

In 2008, respected Canadian aviation historian Hugh Halliday presented Scratch's story at a meeting of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society and more recently, Terry Leversedge, Associate Editor of AirForce magazine wrote the definitive piece on the subject. Unlike many other more lurid accounts of Scratch's story, both of these historians' accounts were based on thorough examination of RCAF service, medical and court-martial records. The Leversedge story came to my attention as I was writing this story and it is a superb and complete record of Scratch's misadventures. Brielfy, I thought that I should abandon this story given the completeness of the AirForce article. However, I decided that it was time that I took my own stab at telling his story for Vintage News since our subscribers are from all over the world and for the most part would not be exposed to his story. Regardless of your take on this, the Donald Scratch story is worthy of a closer look for the events that led up to Scratch’s last ride and for what it tells us about how mental health was understood in the Second World War.

Donald Palmer Whitman Scratch was born in 1919 in Maymont, a small dirt-street farming village in west central Saskatchewan, the son of the town doctor, John Archibald Scratch from Amherstburg, Ontario (near Windsor, ON) and Matilda Maude Learmonth from the tiny village of Kineers Mills in the Eastern Townships of Quebec (near Thetford Mines). In his book, The Great Depression, famed Canadian history writer Pierre Burton speaks of the difficulties of small town prairie medicine, quoting Dr. Scratch, who said “I pull their teeth and lance their boils and deliver their babies. They pay what they can — a chicken here, a ham there.” Donald's parents divorced when he was three and he went to live with his remarried mother (who became Mrs. Whitman) in Ashmont, Alberta, an even smaller community northeast of Edmonton. A future psychiatric assessment would make mention of his “broken home”, but the RCAF psychiatrist stated that it didn’t “seem to concern him much”. He had two older brothers, Dr. Norvel “Pinky” Scratch and Dr. Ronald Scratch, both medical officers serving overseas at the time of his enlistment.

Scratch worked as an apprentice pharmacist in Edmonton (the program was affiliated with the University of Alberta) before he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in the summer of 1940 during the height of the Battle of Britain. Inspired by the stories of RAF fighter pilots like fellow University of Alberta student Willie McKnight, Scratch no doubt longed for nothing short of showing his metal in the skies over Europe. In his service file is a letter of recommendation from Edmonton pharmacist H. W. Rogers that read: “With regard to the above names, [I] wish to say that he has worked for me during the past two years and that I have found him to be energetic, prompt and willing to learn and advance himself. I also wish to say that he is honest and has a splendid character. I am very pleased to recommend this young man and believe that he will be an asset to your Corps.” His service file shows that he was interviewed by RCAF recruiters on 17 June 1940 and was assessed as “Excellent type, gentlemanly, courteous; should make good as pilot; strongly recommended for commission as pilot.”

Though he was interviewed in Edmonton, he was sent by train to complete his induction at No. 1 Manning Depot and his Initial Training at No. 1 Initial Training School, Toronto. ITS training was the beginning of a long process of assessing recruits and selecting those deemed ready for air crew training. He was issued RCAF Other Ranks service number R60973. There have been some reports that Scratch was given a different service number—R70052—upon enlistment and that he received the R60973 number later. Having viewed Scratch's service file, I can find no evidence of R70052 ever being used. Any documents in the file that reference a service number, all bear the number R60973—except for the period when Scratch would become an officer and then his service number was J26269. Scratch graduated from Initial Training 89th in his course of 224 recruits and was thought of as “pilot material, conscientious, quite type, sensitive…”.

An early service file/ID card photograph of Donald Scratch, possibly taken at Manning Depot when he was just beginning his career—as an Aircraftsman Second Class (AC2). Photo: via Moose Jaw Express

Impressing his instructors at No. 1 ITS, Scratch was selected for pilot training and sent north to No. 2 Elementary Flying Training School near Fort William at Lake Superior’s western end (now Thunder Bay’s municipal airport). There he did his ab-initio flight training on de Havilland Tiger Moths. After 65 hours of dual and solo time on the Tiger Moth, he was given a very positive assessment by his instructors: “Appears quite conscientious and sensitive. His flying ability is of a high average. He is very keen and has the right attitude for service life. Should develop into a very good pilot. His conduct has been most satisfactory.” Another instructor wrote by hand on Thunder Bay Air Training School letterhead “This airman's progress has been very favourable. He is exceptionally keen and willing, and while his ability to learn is not startingly fast, he does absorb and retain his instrcucions very well. Because of his keenness and tenacity he should develop into a high average pilot, best suited for twin engine aircraft”. Things were looking pretty good for young Don Scratch.

Successfully completing his EFTS course, he moved back to Central Ontario and No.1 Service Flying Training School at Camp Borden, there to take advanced flying instruction. After 88 combined dual and solo hours on Harvards and Yales, he became a qualified pilot in the RCAF, but the language of his evaluation was tempered somewhat from the earlier EFTS assessment: “Steady pilot, good on instruments” … “Anxious to learn.” By the tough standards of the day, this was in fact a very positive endorsement.

An early photograph of Sergeant Don Scratch, most likely taken shortly after his graduation from No. 1 Service Flying Training School in Camp Borden, Ontario. He seems a rather mild-looking man in this portrait which contrasts strongly with one taken later in his career. Photo: Library and Archives Canada via Hugh Halliday

Related Stories

Click on image

Upon graduation in late April, 1941, Scratch was promoted to Sergeant and was assigned to No. 118 Squadron (Fighter) at RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa. He must have been overjoyed to be sent to a fighter squadron even if they were flying the disappointing Grumman G-23 Goblin. He would have learned that soon they were to transition to the Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk, so the future was looking bright for the former pharmacist's assistant. He joined the squadron on May 1, but by June 12, he had left Rockcliffe and all his hopes for becoming a fighter pilot behind. Wing Commander Ernest Archibald McNab, 118’s Commanding Officer and a Battle of Britain veteran fighter pilot, wrote in his file: “A sound pilot but not considered fighter pilot material.” It’s likely he would never see this in his file, but his commanders would possibly have told him so, and likely he was stung by the back-handed compliment. It would be the first of a string of setbacks that would in time weaken his confidence and eventually break his spirit.

Grumman G-23 Goblins of No. 118 Squadron RCAF in formation. Canadian Car and Foundry license-built 52 Goblins in Fort William, Ontario at the outset of the war. Most made their way to Spain, but 15 were reluctantly accepted by the RCAF and supplied to 118 Squadron as a stop gap measure in the first months of the war. In the summer of 1941, Scratch joined 118 at RCAF Station Rockcliffe only to be deemed not “fighter pilot material” within the month. Given his future illegal displays of piloting skills, his flying ability was not the reason for his being cut from 118 Squadron. Photo: RCAF

One day after being let go from 118 (Fighter) Squadron, Don Scratch found himself on a train for the RCAF’s Eastern Air Command headquarters in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Here he was given orders to join 119 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron, a Bristol Bolingbroke unit flying anti-submarine patrols from Yarmouth at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy. 119 Squadron was a fully operational unit but it also acted as a de facto operational training unit, bringing pilots up to speed and assessing them. After nearly 6 months on squadron, he was judged “Below average (erratic) on twin engine aircraft; believe this pilot’s heart is not in bomber reconnaissance work.” The assessment included a recommendation that he should return to single-engine aircraft, and since he was previously deemed unsuitable for fighter pilot duties, this would mean either becoming a staff pilot at a bombing and gunnery school (Lysanders and Fairey Battles) or as an instructor pilot at an Elementary or Service Flying Training School Tiger Moths, Harvards etc.). As it turned out, he was kept on squadron, but one wonders if this comment meant that he was having early difficulties with the multi-engine Bolingbroke.

119 Squadron Bristol Bolingbroke Mk IVs in formation over Nova Scotia. The “Bolly” was a Fairchild Canada licence-built variation of the Bristol Blenheim Mk IV with Mercury XV radial engines. Fairchild built 626 “Bollys”, most of which were employed in anti-submarine and coastal patrol by Home War Establishment fighter squadrons on both coasts or as multi-purpose trainers at Bombing and Gunnery Schools of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Photo: RCAF

Despite his early negative assessment, Scratch was promoted to Flight Sergeant on December 1, 1941. In early January, 1942, 119 Squadron moved its base of operations to the north of Nova Scotia and the industrial port of Sydney on Cape Breton Island. Not long after his arrival there, Scratch met with disaster.

Early in the morning on March 16, Scratch and his crew briefed at Sydney for an anti-submarine patrol over the Atlantic. It was a typical late winter day on the Atlantic coast— just below freezing and overcast with a ceiling of 6,400 feet and eight miles visibility. At 0655 hours, as they were rolling on take-off from Sydney in Bristol Bolingbroke 9064, the starboard Bristol Mercury engine “missed” one third of the way down the runway. Scratch continued the take-off roll and became airborne, climbing steadily southeast to about 300 feet AGL and then initiated a climbing turn to starboard. Shortly thereafter, the starboard Mercury sputtered and died altogether and the aircraft lost airspeed and altitude rapidly. Turning around Grand Lake in an attempt to get back to the airfield, the aircraft “flew over the railway tracks, broke a high-power tension wire, and still losing altitude skimmed along tree tops, stalled and then with right wing low crashed to ground, totally damaged.”

A computer-generated illustration of a 119 Squadron Bollingbroke identical to the Bolly that Scratch was flying on March 16, 1942 when he crashed near Sydney, Nova Scotia. Photo: asisbiz.com

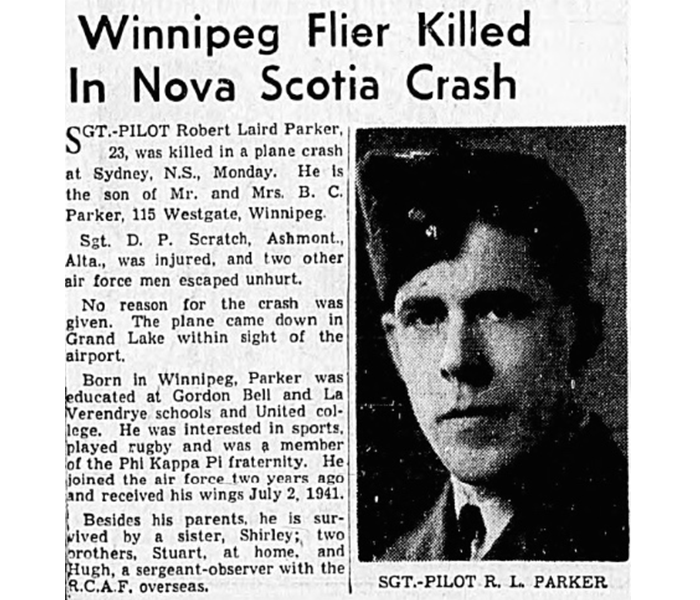

The Bolingbroke suffered Category A damage and was soon to be written off, but the real damage was to Scratch and his crew. While air gunner Sergeant D. G. Dickson and wireless operator Sergeant F. A. Connolly were slightly injured, navigator Sergeant Robert L. Parker1, by some accounts a close squadron friend, was killed and Scratch himself was gravely injured. In addition to second degree petrol burns, Scratch suffered bilateral fractures of his ankles. He was hospitalized for six months. His recovery was slow and painful. The fallout from the accident went beyond the physical injuries however. A later psychiatric assessment of Scratch (prior to his later court-martial) stated that during the period of hospitalization “he had repeated nightmares of horrible flying situations, in which things got out of control and just as he was about to have a serious accident he would awaken. He was usually trembling during the time with perspiration, tense with fright. He was able to go back to sleep after a while. The situation continued for about a year.”

A newspaper clipping from a Winnipeg newspaper. Following the Bolingbroke crash near Grand Lake, Parker's body was recovered and returned by train to Winnipeg where it was buried in St. John's Cemetery. I believe that Parker's death impacted Scratch's mental state throughout his recovery. Perhaps he wondered if there was anything he might have been able to do to get the aircraft on the ground safely instead of stalling and spinning in. Should he have aborted the take off when he first heard the starboard engine missing? If he had been wings level instead of in a right bank when the right engine failed, would he have been able to check the right roll and land the airplane as most assuredly he had been trained to do? I am sure these are things he would have thought about in the endless and pain-filled hours, days, weeks and months of his recovery. Though his actions that day were not mentioned as relevant in the resulting crash investigation, he had to answer to himself I am sure. Clipping: Canadian Virtual War Memorial

Though there is no instance of Service No. R70052 in Scratch's service file, it appears on the “crash card” for the Bollingbroke crash and this administrative mistake is likely how that number entered Scratch's story. Image via Jerry Vernon

The finding of the investigating board was that the cause of the accident was the failure of the starboard engine due to faulty “sparking” plugs. They made a recommendation to all squadrons operating aircraft with Mercury XV engines — “inspect, break down and clean plugs every 40 hours. ” It’s likely that this recommendation would save lives as the war progressed, but it was too late for Parker and Scratch.

During the summer of his recovery, Scratch was promoted to Warrant Officer Second Class. His approved promotion order stated “Excellent type of airman. Fully qualified and worthy of promotion.” In September of 1942, an RCAF doctor concluded that he was ready to resume flying duties, though he should be fitted with “special supports”. This was however not the end of the pain and debilitation caused by the accident. Two years later, following the aforementioned court martial, Scratch himself would state in a signed affidavit that “I have been bothered almost continuously with my ankles and feet since they were injured in an aircraft crash at Sydney, N.S., 16th March 1942, while in the line of duty, namely, an operational patrol. I have resumed flying duties and find that my feet are strong enough to operate the controls properly. Continued weight on them such as working or standing necessitates a rest period because of pain brought on by these actions. I am unable to run, and have difficulty descending stairs. This is due to the stiffness that is apparent in both, but more marked in the right ankle. This disability would seem to me to be a permanent one. All of my movements are hindered by my feet which give me pain and discomfort except when sitting or lying down and as a result I am unable to do manual labour. Weather also bothers them and cold and dampness likewise causes them to ache.” As someone who shattered his ankle and broke both his knees in an accident a decade ago, I have considerable sympathy for his plight.

Though his recovery was slow, painful and lonely, Scratch was commissioned as a Pilot Officer (With a new Service Number—J26269) in March of 1943 and was finally reinstated to flying duties in early May of that year. He was first sent to join his squadron which was now stationed in Mont Joli, Quebec on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. The home of No.9 Bombing and Gunnery School, Mont Joli station was also a base of operations for aircraft conducting anti-submarine patrols in the Gulf of St Lawrence during the “Battle of the St. Lawrence” from May 1942 to November 1944. He spent one month there getting up to speed on flying operations with his squadron.

After a month of flying at Mont-Joli, Donald Scratch was transferred to Gander, Newfoundland in June, there to train on the Consolidated B-24 Liberator which was used by the RCAF for long-range anti-submarine operations far out into the Atlantic. Things must have gone without problem during this short period at Gander as he was promoted to Flying Officer on 23 September. However, it was also at this time that his problems with pain and the strength in his ankles began to tell. Flying a massive heavy bomber like the “Lib” required stamina and his injuries were beginning to put doubts in his mind and in the minds of his commanders.

A terrific ID photo of Flying Officer Donald Palmer Scratch—taken after his recovery from his grievous injuries and after his promotion to that rank on 24 September, 1943. One thing for sure, Scratch was a well turned-out officer in His Majesty's Royal Canadian Air Force. He exudes confidence and looks every inch a competent pilot. Photo: Library and Archives Canada via Hugh Halliday

On 16 October of 1943, Scratch officially joined No. 10 (Bombing and Reconnaissance) Squadron at Gander, Newfoundland, a highly successful RCAF unit that would attack 22 and sink 3 U-boats before war’s end and become known as “The North Atlantic Squadron”. Unlike the Bolingbroke, the big four-motored Liberators of 10 Squadron required two pilots to operate its complex systems and share the tiring flying work of long over-water patrols. Rookie pilots on squadron took the role of co-pilot to the crew's commander and first pilot. An RCAF pilot could assume that eventually, with operational experience, proven performance and squadron attrition, he would move to the left seat and become a “captain”. Given egos, nearly all pilots strove for this increased responsibility and control, as this was the fastest way forward for promotion.

Scratch's name appears for the first time in the squadron ORBs on that very day (Oct. 16), up flying a few local circuits with his commanding officer, Wing Commander M.P. Martyn, Flight Lieutenant J. Sanderson and a wireless operator and later doing a short cross-country flight with a full crew to Torbay on the Avalon Peninsula—both familiarization flights. A month later, on November 16, Scratch flew a few circuits with three other pilots aboard, including Wing Commander Martyn. This was likely some sort of assessmnet of his progress. By the end of November, he had yet to fly an operational sortie. Reading through the ORBs for the first 8 weeks of his time at 10 Squadron, Scratch did not seem to get much flying in—only 14 flights in the first month and a half, and these primarily local circuits. I wonder if this indicates that he was having some difficulty or that commanders were not quite sure about his ability?

There is no evidence in the ORB that Scratch flew in the two weeks of December, and then by December 13 he was in Alberta to attend a course on Chemical Warfare at Experimental Station Suffield. The course involved some flying in both Bolingbrokes and Lysanders and his assessment included the following statement: “A very capable pilot. Was interested in the material covered and the course. Could have made better grades had he applied himself more diligently. This officer’s co-operation was noteworthy.” Scratch placed 4th out of 6 in the class. He returned to long-range operations with 10 Squadron at the end of the year. It is also possible, since he was back in Alberta and the course ended on Christmas day, that he might have visited his mother for the holidays or his father in Saskatchewan on the way home.

A Consolidated B-24 Liberator of No. 10 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force parked on the ramp at Gander, Newfoundland. When they arrived on the scene, shore-based Liberators had a powerful impact on U-boat operations in the North Atlantic. Combined with shipborne ASDIC (sonar) and high-frequency direction finding (“huff-duff”), the end was near for Admiral Dönitz' submarines. Photo: RCAF

Upon review of the 10 Squadron ORBs in first six months of 1944, I found that Scratch flew as second pilot to a series of aircraft captains—Flight Lieutenant J. Sanderson, Flight Lieutenant J. P. Dale, and Flying Officer A. P. Chester and a single flight with Wing Commander Martyn who appeared to be evaluating Scratch during local circuits. A few other things were noteworthy. To begin with, Scratch seemed to fly considerably less than many of the 10 Squadron pilots. Secondly, on 3 June, 1944, he was paired with Flying Officer R. F. Bedford and would fly all his remaining operations at 10 Squadron as co-pilot to this officer. This is interesting in that Bedford arrived on squadron after Scratch and flew as a co-pilot himself for five months before getting the left seat, and when he did, Scratch was made to fly with him. I suspect that having to be second pilot to one of his peers (one who had certainly earned his place in the left seat), was another blow to his ego. Scratch felt that the injuries he sustained almost two years previously were keeping him from his captaincy and he may have been right. Flying the Liberator was physically demanding, requiring, at times, considerable arm strength with the yoke and sustained pushing with his feet on heavy rudder pedals. The issues with strength and endurance would compound over 15-hour missions and in times of emergency—especially with an engine shut down. There is no record of how this manifested itself in the case of Scratch. Did he complain about pain and weakness? Did various aircraft commanders notice problems with his flying or perhaps a lack of endurance?

There is no doubt that his lack of advancement despite nearly three years flying on operations weighed heavy on his mind. Later psychological assessments found that he “Worried about it a great deal and there was considerable evidence that his future as a pilot occupied much of his thought.” Most young men in this situation might consider working harder at building strength or perhaps resign themselves to their fates. It is likely that Scratch would have asked for a transfer to a European combat theatre or another type of flying since later he would express his dissatisfaction with anti-submarine flying in the Home War Establishment.

This page from the 10 Squadron Operations Record Book (ORB) shows us the type of mission that Scratch was flying in the summer of 1944. Up at probably 02:30, briefing and then launching at 04:20 in darkness. He flew convoy escort as second pilot out over a featureless ocean at a time when there was much less U-boat activity in the Western Atlantic, then returning after 15-long and gruelling hours. When one takes into account his isolation at Gander, his family woes, his mental health following the accident and these long stultifying missions with no hope of advancement, one can find sympathy for Scratch's mental perspective, especially in light of what we now know about PTSD. Scratch had also come through a particularly harsh winter at Gander, with long hours of darkness and little sunlight during daylight hours. In the month of January, 1944 alone, the base administered 860 “ultraviolet lamp treatments” (photo therapy designed to treat a wide array of maladies in lieu of sunlight). Even back then, doctors in Canada and Newfoundland recogized the deleterious effects of prolonged periods without sunlight in northern climes—which we now call Seasonal Affectiveness Disorder. Photo: Hugh Halliday

I am not sure exactly what went through Flying Officer Scratch's mind through the first six months of 1944, but in mid-June, something snapped and he did something that changed the course of his military career and indeed his life—he stole a Consolidated B-24 Liberator, one of the largest aircraft types employed by the Royal Canadian Air Force at the time.

On Monday, 19 June, the weather at Gander was very poor, even for the North Atlantic Squadron. Winds gusted to 50 mph, while the station was lashed by rain showers and ice at altitude. The temperature hovered near the freezing mark and safe flying was not possible. 10 Squadron stood down for the day, and the Officers' Mess would have been busy, smoky and loud. At one point after dinner, Scratch approached his CO, Wing Commander M. P. Martyn (eventually Air Vice Marshal Martyn) with a drink in his hand and asked him “how long it would be before he would be considered for a captain's position”. Martyn “told him that his future depended entirely on himself and he replied that he was going to work as hard as possible to qualify himself for such an appointment.”

Some stories, possibly apocryphal, have said that on that night, there had also been a lively discussion over many drinks in the mess as to whether a Liberator could be started, taxied, flown and landed by one man only. The general consensus was that it was far too complex to be managed by a single pilot through all phases of flight. Whether this “argument” took place or not, in the wee hours of the following morning, Flying Officer Donald Scratch left his quarters and made his way to the flight line, selected 10 Squadron Liberator with the aircraft code “Y” (a bare metal former RAF Liberator G.R. V with RCAF Serial 596), walked around it to remove the chocks, opened the crew door inside the bomb bay, climbed inside, made his way up to the cockpit and strapped himself into the left seat. It is not recorded in any of the official documents I have been supplied, but it is likely that he was still drunk.

In the dark and without any help, he primed and started all four engines, unlocked the brakes, pushed the throttles forward and moved out of the flight line, rolling in the dark towards the runway. 10 Squadron often launched long-range patrols at ungodly hours, and ground crews were always testing engines throughout the night to ready aircraft for the next day's flying, so one Liberator starting up at 0345 (times differ depending on the report) and taxiing along the flight line may not have immediately aroused the suspicions of maintainers on the ground.

Gander at this time was enormous, one of the largest stations and airfields in North America. In addition to being a base for anti-submarine operations, it was a refuelling station for aircraft transiting the North Atlantic and a staging field for combat and transport aircraft being ferried from factories in North America to Europe. All kinds of aircraft came and went at all hours at Gander, so the taxi lights of a big Liberator moving out of the flight line was not at all out of the ordinary for the mainentance staff. Also, the design of the runways and ramps at Gander meant that a departing aircraft did not move along perimeter taxiways, but could simply roll forward on to the runway and backtrack to the threshold. At 0345 hrs, the Flying Control Officer (FCO) in the tower received a radio call from Scratch in “Y for Yolk” requesting a radio check. The FCO sent “a few check calls” and then waited for a reply. Then he heard the Liberator powering up its engines as if to take off and he used his binoculars to spot Scratch on the runway (the number of the runway in the blurry document is not readable).

Then Scratch actually radioed for permission to line-up for take off. The FCO directed him to the runway in use (too blurry to positively make out in document—possibly 06?) and Scratch taxied with permission. The FCO then contacted Operations to inquire as to whether it was a patrol aircraft and was informed that they had no knowledge of an aircraft scheduled to fly. He then radioed the pilot in the Liberator to ask if he was on a local flight, and Scratch replied in the affirmative. Scratch, sitting clear of the runway, then asked for clearance to move to take-off position, and was cleared. Scratch then taxied (backtracked) between the flares and was then instructed “to line up between the flares into the wind”. He was subsequently given permission to take-off. The FCO testified that Scratch commenced his take-off roll and, after travelling a short distance, cut the throttles. The FCO asked if there was a problem and Scratch replied “No”, asking for permisssion to turn around and move back to the take-off position. This was granted, but he was asked to hold there and the FCO got no reply. The FCO called three times without a response and asked the Liberator to flash its landing lights if he was reading the tower. This Scratch did.

An aerial photograph of Gander, Newfoundland's massive facility with its wide ramp, through which Runway 27-09 runs. It is clear from this photo that all Scratch would have had to do was pull out straight to the runway and backtrack to the threshold. The USAAF and the Royal Air Force each developed sections of the triangular base for their own use, but the airport remained under overall Canadian control despite its location in the Dominion of Newfoundland, not yet a part of Canada. During the 911 attacks on 2001, 38 massive airliners were forced to land and take refuge here. One look at this ramp and you know they had room!

The FCO then left his desk and called the hangar to ask if anyone knew who was scheduled for a local flight. Checking the log books for 10 Squadron, it was clear to those on duty in the hangar that the log book for Liberator “Y” had not been signed since the day before. The FCO then hung up and was returning to his control desk when he noticed that Liberator “Y” was commencing a take-off. He picked up the signal light and held a steady red light (the signal to STOP) on the rolling Liberator until he was airborne. The time, he noted, was 0400 (this may be incorrect as it is hard to read the document).

One can only imagine what was going through his mind and what compelled him to bring the Liberator around into the wind in the dark on that morning. As an officer in the RCAF, Scratch had to know that his actions would result in an immediate arrest if he managed to survive. Despite his qualifications and experience on a Liberator, he would never have been able to simply take one up without a purpose that had been pre-determined and approved by his squadron commanders. This he knew. Was he making some sort of statement about his unhappiness with his present contribution to the war effort? Was he trying to prove that he was perfectly capable of flying a Liberator for hours despite the handicap presented by his injured ankles and his commanders' insistence that he was not capable? He had to know that his entire, up-to-now, respectable career would end the moment he touched down, yet sitting there alone in the dark in the middle of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he chose to open the throttles, take his injured feet off the brakes and begin his take-off roll.

According to the 10 Squadron Daily Diary for 20 June, “At approximately 0430 hours local time [there are discrepancies in the time in various documents] a weird and wonderful exhibition of low flying and shooting up the barracks was put on my F/O D. P. Scratch. He took off single-handed in Liberator “Y” and was air borne for approximately 4 hours.” Though the weather had been atrocious the day before, it had cleared somewhat with good visibility on Tuesday and the sun was due up at 0503 hours. Scratch climbed steadily into a dim but gradually lightening grey sky and one can only imagine his thoughts as he climbed out. He probably understood that even if he turned around and landed right away, the outcome would be the same—a court-martial and dismissal from His Majesty's Royal Canadian Air Force. He checked his fuel situation and set out on what can only be called a joyride—a four hour display of his flying skills that found both admiration and condemnation.

For the next few hours, Scratch not only single-handedly flew the Liberator that couldn't be flown by one man, he flew it aggressively and at extremely low levels for hours. At the same time as solo piloting the massive heavy bomber, he performed the role of a navigator when he flew 200 kilometers south to United States Naval Air Station Argentia on the west coast of the Avalon Peninsula where he repeated his display of low-level beat-ups of that airfield. There have been far-fetched claims published of American P-40 pilots having been scrambled from Argentia to intercept him and force him down, reporting that he was seen rotating the top turret of the armed bomber while the aircraft flew on auto pilot. While Argentia was indeed an American airfield, it was a Navy airfield and the US Navy did not have P-40s or even fighters based at Argentia at the time, nor did the United States Army Air Force. 129 Squadron of the RCAF's Home War Establishment was based in Gander at the time of the Scratch incident and though their ORB mentions four of their Hurricane Mk XII aircraft flying off on an “interception” starting at 0855 hrs and landing at 1025 hrs, the 10 Squadron ORB states Scratch was aloft at 0430 and down approximately four hours later (0830). If these times are accurate, then these Hurricanes, the only fighters stationed in Newfoundland at that time, were not up when Scratch was up. The story of Donald Scratch was extraordinary enough, that these added theatrical embellishments serve only to discredit the whole story — more Hollywood than Gander.

Following several low beat-ups of Argentia, Scratch flew back north to Gander and continued to fly back and forth over the base at extremely low levels until the Station Commander in the tower finally raised him on the radio and ordered him to land immediately. Being the well-trained airman and obedient officer that he was, Scratch finally came to his senses, replied “Yes, I will do it.” and ended his ill-conceived flight, bringing the Liberator in for a landing and full stop. As he taxied up, there were service police on hand along with his squadron commander, Wing Commander Martyn and the Station Commander. Martyn and the commander followed Scratch up the runway in a car and Martyn got out when Scratch stopped, and walked around to the front of the aircraft, signalling Scratch to roll up the bomb doors. Scratch complied and Martyn climbed through the crew hatch and found Scratch in the left seat trying to restart the Auxiliary Power Unit, which had quit for lack of fuel.

Martyn then ordered him to the right seat, but Scratch was reluctant, saying he would like to finish the flight himself by taxiing back to the parking stand. He eventually complied and Martyn took command of the Liberator and taxied back to the flight line, with Scratch assisting him on shutting down. During the taxi back, Martyn asked him why he had carried out such a performance. Scratch replied that he was “getting tired and had been here too long.”

He was under close arrest at 0940 (Z) that same morning and confined to a detention cell. A strange night's work. Despite the drama of the early morning, 10 Squadron continued operations without missing a beat, launching seven training and convoy escort sorties that day. Two days later, Liberator “Y” was flying again, none the less for wear after Scratch's aggressive flying demonstration.

Scratch would spend the next 2 1/2 months under arrest. He was not to leave the quarters assigned to him and could not receive visitors or any communications save his personal mail. Denied mess privileges, he took his meals alone in his room and any exercise would have to be approved by the medical officer and carried out in the company of a provost escort. If he was allowed out for one of these escorted walks, he could not enter any buildings or have any convesrations or communications of any kind with anyone. On 14 June, he was informed that his court-martial was four days hence and served with a document outlining the three charges brought against him — 1) Flying Liberator “Y” without authorization; 2) Taking off in said aircraft after being refused permission by the tower; 3) Flying at low levels without aurthorization.

An entry in the Gander Station Diary of 18 July, 1944 reads “A General Court Marshall was convened today to try Flying Officer D.P. Scratch of 10 Squadron on three charges connected with low flying and unauthorized use of a 10 Squadron aircraft [from the Gander Beacon, September 29, 2017].” It was four years to the day since Scratch enlisted in the RCAF. He would be convicted on all counts.

In his defence at his court-martial, Scratch told investigators that his actions were brought about by his “isolation and inactivity and his strong desire to do something active”. In addition to the injuries and possible post-traumatic stress disorder, two other family issues had begun to impact his perspective. His 58-year old father, still a practicing physician in Alberta, was suffering from some form of cancer and his mother's health had declined seriously since she learned of his Bolingbroke accident, injuries and hospitalization in Sydney. According to his post-incident psychiatric assessment, she had taken “to bed with cardiac complaints which were apparently precipitated by the patient's accident”. There was a lot on young Scratch's mind the night he got it in his head to fly a Liberator by himself.

On 2 September, 1944, a depressed and humiliated former Flying Officer Donald Scratch was dismissed from His Majesty's Royal Canadian Air Force. While there did seem to be some sympathy by psychologists for his plight and professional admiration by his colleagues for his flying, there was no understanding of the long-term effects of what we now know as PTSD. The consultant's report after a single interview with Scratch stated in part: “During the interview the patient was calm, spoke well, somewhat reticent, but gradually told his story. He does not appear concerned or anxious. There is no evidence of depression or psychotic behaviour and thinking.” In the space on the form for diagnosis, the consultant wrote “No psychiatric illness at present, although I am certain that for a year following his crash the patient suffered psycho Neurosis, Anxiety State.”

At the bottom of the report from the psychiatric consultant brought in to inteview Scratch, just above the consultant's signature, is a sentence followed by a line to fill in. This sentence reads “Is this man fit for duty?” On Scratch's report, the consultant wrote in the space alotted: “He is at present fit for all duties.” This may have sealed Scratch's fate, for though he was cashiered from the RCAF, he was, as we will see, shortly thereafter allowed to re-enlist.

“Fit for all duties”. The final thought on the consulting psychiatrist's report to the RCAF concerning Scratch. Photo: Hugh Halliday

Scratch, likely in his civilian clothes and somewhat broken, left Newfoundland and, when back in Canada, boarded a train and began a long and lonely journey home. What he did next is not known. I wondered if at first he went home to visit his ailing mother in Alberta or his dying father in Saskatchewan, but is seems to me he did not have enough time to do this. Perhaps he was too ashamed of the situation he got himself into, but what we do know is that in his personnel file there appears a document from R.C.A.F. Special Reserve letterhead dated 14 September that tells us that no more than 12 days after his dismissal in Newfoundland, he was applying for re-enlistment at No. 3 Training Command Recruiting Unit in Montreal.

A memorandum dated September 18, also on RCAF Special Reserve letterhead and signed on behalf of the Chief of Air Staff, shows Scratch was being allowed back into the air force. At the top of the memo is Scratch's commissioned service number (J26269) and at the bottom is his old NCO number (R60973) It's almost hard to believe, but the memo states that he had “been examined and ... is qualified as an Airman Pilot, A.C.2 “Standard” Group.” It goes on to say that “in the event of enlistment, applicant is to be remustered to Special Group [not sure what that means], effective date of enlistment and appointed to the rank of Temporary Sergeant (Paid) effective day of enlistment.” This was on a Monday and by Thursday the 21st, he had re-enlisted at Montreal, was given his original RCAF Other Ranks service number (R60973) and was now a sergeant again. In his second set of Attestation Papers, Scratch listed his present address as Bell's Lodge, a rooming house at 1201 Dorchester Street, Montreal. He soon checked out, boarded a train and reported the next day to the same Manning Depot in Toronto where his career had started four years previously.

One wonders if Scratch had known when he was cashiered that, while the door had been slammed shut in his face, the RCAF had opened a window for his return. Had he been told that the RCAF was open to reenlistments because of a pressing need for pilots? It does seem like a short time between his dismissal and his re-enlistment. Whatever had led him to Montreal, Scratch chose a fresh start, an opportunity to make amends for his lapse in judgment. One thing for sure is that, in the 16 days since he left 10 Squadron, there was no way he had yet resolved the anxiety and PTSD-like issues that had led to his Liberator escapade and dismissal, despite the finding of the psychiatrist that he was “fit for full duties”.

A remarkably telling photo of now-Sergeant Donald Palmer Scratch. This identity card photograph was attached to a document that was dated 26 August, 1944, during the time of Scratch's incarceration at Gander and a week before his dismissal. This same document also noted him as still an officer with his old commissioned Service Number J26269. He remains well-groomed, more handsome than before, but the knot in his brow, the firm set of his mouth and cold look in his eyes tell a story of a troubled young man. Photo: Library and Archives Canada via Hugh Halliday

A few days later, Scratch was on a train to the West Coast of Canada and No. 5 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RCAF Station Boundary Bay, part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan's No. 4 Training Command. Boundary Bay airfield was on the shores of the eponomous bay on Georgia Strait—a beautiful place to fly if there ever was one and not at all like isolated and weather-socked Gander, Newfoundland. No. 5 OTU was training pilots to fly the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, the same aircraft that Scratch had been flying in Gander. Most student pilots at No. 5 arrived straight out of a Service Flying Training School at which they would have flown one of three tail-dragging types—the Avro Anson, Cessna Crane or Airspeed Oxford. The Liberator had nose-wheel steering, and while tail-dragger aircraft were in fact harder to fly, a tricyle-geared behemoth like the “Lib” required plenty of adjustment. No.5 OTU had an equal number of North American B-25 Mitchell bombers that were used for transition flying—twin-engined medium bombers used to get student pilots familiar with nose-wheel operations before moving on to the intimidating, slab-sided, four-engine B-24.

North American B-25 Mitchell bombers of the Royal Canadian Air Force line the flight line at No. 5 Operational Training Unit, Boundary Bay. By August of 1944, before Scratch arrived on station, there were 41 Mitchells and 36 Liberators2 on the flight line. It was here, in late 1944, that Sergeant Don Scratch stole one of each. Photos by Noel Barlow, DezMazes Collection, via No.5 OTU Facebook Page

No.5 OTU was primarily in the business of training full crews on the Liberator—pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, wireless operator and gunners—to fill RAF Squadrons operating in Southeast Asia and Burma. Some Canadian students at No.5 were then diverted to coastal patrol at either Western or Eastern Air Command.

Poor Scratch found himself still in the right seat despite the fact that he had been an operational multi-engine pilot for a few years. His joyride flight at Gander had certainly proved his ability to fly but not his ability to make good decisions. Though he was lucky to still be flying, Scratch was likely still frustrated at not having the captain's seat. Later, one of his instructors, Flight Lieutenant Vincent Joseph Faurot, DFC, of Niagara Falls, a veteran 226 Squadron Mitchell pilot with experience on operations in Great Britain said, “He was a very keen average pilot; neat in appearance with a pleasant personality. He was very quiet and generally well-liked”. Not exactly a ringing endorsement of Scratch's flying skills, but an honest assessment not coloured by hindsight.

According to Terry Leversedge in “The Strange and Sad Case of Sergeant Donald Scratch, Revisited” (AirForce Magazine, Volume 41, No. 4, March 2018), Scratch had been on sick call:

“For unknown reasons, for a total of 19 days in November, Sgt. Scratch was receiving medical treatment, having first reported sick on 11 November. By 30 November, Sgt. Scratch was pronounced “cured” by the station's medical officer, Squadron Leader (S/L) C. A. Badger. S/L Badger later testified"

In the 19 days in November that he was under my care, I had occasion to interview him 3 times, one of these interviews being 1 hour long. I have no hesitation in saying that I feel this man was at the time quite sane. The... treatment in my opinion had no affect [sic] on his subsequent actions.”

Having reviewed Scratch's service file and attached medical reports, I can say that Scratch was in the care of Badger for an embarrasing and recurring condition entirely unrelated to any issues regarding his mental health.

One week later, Scratch's world fell completely and fatally apart.

The Mayo Clinic lists “self-destructive behaviour such as drinking too much” as one of many symtoms of PTSD and it was not the only one that Scratch seemed to exhibit since his accident. On the evening of 5 December, 1944 with only six days left in his B-25 conversion course, Scratch went to dinner at the mess, dining with friends and drinking. According to others, Scratch was not a heavy drinker, but that night he went on a mini-bender.

That evening, Scratch bought “between 12 and 18 bottles of beer” (though it is not confirmed that they were all for him) and then later three more at last call.

I'm no doctor, but that much alcohol had to have seriously impaired 140-pound Sergeant Donald Scratch's ability to think properly. Somehow, after the bar closed, Scratch also managed to acquire a bottle of Jamaica Rum. At around 0200 hrs, Scratch made an appearance at Boundary Bay's signals office where he asked for a light from Corporal Jocelyn Catt, the WD on duty. He leaned against the teletype and chatted with her a short while, then offered her a swig from his mickey (she testified that it was almost full). Turned down, he took a swig himself and showed her his ID, telling her that he recently been in serious trouble for low flying. He left and was next seen an hour and a half later in one of the hangars asking for another light from LAC Thomas Cooper, an aero-engine mechanic on duty. He asked another airman present if he had a book of matches and insisted on paying him a penny—for good luck. He may have been fighting a dark urge by talking to people, looking for friendship, or he may have been deliberatly working his way to the flight line with the intent to reprise the terrible mistake he made at Gander.

Sometime after his smoke at 03:30 hours, Scratch made his way out to the flight line at Boundary Bay. It was a cold coastal winter night, not freezing, but at 35 degrees F, not much warmer. Scattered clouds and overcast above obscured a waning third quarter moon. While mechanics worked inside the flight line hangars, a drunken Donald Scratch, walked down the long line of looming Mitchells and Liberators, and when he was far enough away from the hangars and maintenance activity to be heard or seen, picked out Liberator EW282, dragged the chocks away and slipped through the crew hatch.

During the weeks that he had been at Boundary Bay, Scratch had been on the B-25 course and likely had not flown a B-24 since 20 June in Gander. As he had done several months before, he strapped himself in, began priming and starting all four Pratt and Whitney engines. He stowed his bottle of rum next to his seat on the left side, rolled the bomb doors closed, eased on the throttles and pulled out of the line, swung east along the flight line, rolled past the darkened forms of the remaining Mitchells and Liberators arrayed for the coming day's flying. As he lumbered along the darkened concrete, the powerful sound of the four 1,200 hp engines thundering across the field alerted no one.

Scratch came to grief almost immediately.

As he rounded a corner at the end of the taxiway, and now on a southeast heading, he was moving at a good clip. At the end of that short portion of the taxiway, he had the option of turning back west and taking off from Runway 25, or turning 90 degrees to the southwest for Runway 20. He did neither.

In the dark, Scratch simply missed the two options alltogether, possibly mistaking a service road ahead of him that led to the base magazine as the runway or a continuation of the taxiway. At considerable speed, he rolled the big Liberator off the tarmac, bounced across “200 yds of soft ground4” and plunged headlong into a drainage ditch that ran parallel to the road. The nose wheel sheared off and the Liberator collapsed onto its belly with the massive thrashing propellers striking the face of the ditch. The momentum of the aircraft carried half of the big bomber across the ditch with the front half grinding to a shrieking stop on the road itself.

Though no one from the hangar line heard Scratch come to grief at the far end of the field, the violent drop inside the cockpit must have been explosive and shocking. All four propellers struck the ground with those of engines 1 and 3 hitting so violently that their reduction gear shattered and their propellers sheared off.

An aerial photograph of RCAF Station Boundary Bay from about 10,000 feet during the Second World War. Scratch took a Liberator from the flight line at top, and drove it into the ditch along the service road on the right of this photo. Line of taxi and likely location of wrecked Liberator indicated. The road led to the station's magazine.

An aerial view of the airfield today showing that the runway and taxi plan has remained the same since the Second World War, though not all runways are functioning today.

Scratch then clambered out of the Liberator's command seat, leaving behind a 2/3 full 13 oz mickey bottle of Jamaica Rum with his finger prints on it and exited the aircraft. Sitting on its belly, it is likely that the normal exit from the cockpit through the bomb bay was no longer an option, nor was the hatch in the nose used by the bomb aimer. Perhaps he squeezed out through one of the two sliding windows in the cockpit or worked his way back to the rear compartment and out through one of the fuselage hatches. Perhaps he stood there for a few minutes thinking about the mess he had gotten into again and his options, few as they were. It was dark and he was drunk, but he had to have seen the damage and the missing propellers.

The scene at Boundary Bay after Sergeant Donald Scratch's fatal escapade on 6 December, 1944. In the pitch black of a December night, a drunken Scratch missed the turn for the runway and taxied Liberator EW282 at speed right off the tarmac, across a wedge of infield and came to grief in a drainage ditch. It wasn't until 0815 hrs that anyone discovered it out on the field, and this was likely because the station was fully occupied by Scratch's illegal flying display in the B-25. Judging by this photograph, he must have been moving very fast, for the front half of the Liberator has cleared the ditch and is lying on the road. The nose wheel of a Liberator is just forward of the cockpit, but EW282's nosewheel oleo had to have been sheared off in the ditch while the forward momentum of the aircraft took it well past the ditch. The fabric-looking pile just to the left of the propeller on the road I believe to be inflatable rubber bladders which will be used to lift the starboard wing of the Liberator. Photo by Rohovie, DezMazes Collection, via No.5 OTU Facebook Page

Liberator EW282 with its badly damaged No. 1 and No. 3 engines covered by tarps and the starboard wing lifted through the use of a stack of inflated rubber bladders. Crews at training bases had plenty of experience recovering damaged aircraft on the airfield itself as well as from off-base locations. They had the equipment they needed on hand and had this Liberator extricated by 8 December and towed to the hangar for assessment of the damage. The recovery crew that was sent to the crash site where Scratch finally crashed in another aircraft 5 hours later had a far grimmer job ahead of them. Photo by Rohovie, DezMazes Collection, via No.5 OTU Facebook Page

A good look at the work required to pull the Liberator out of the drainage ditch. Six rubber bladders have been inflated beneath the starboard wing (the air compressor stands on the road) and bridges have been made to span the ditch for work and to roll the aircraft out. The damage to Liberator EW282 was extensive. It was hauled away 2 days later to the base maintenance hangar. A repair crew from Canadian Pratt and Whitney arrived on New Year's Day, 1945. The repair work was not completed until eight months later and by then the war was pretty well over. The aircraft flew only one more time—to nearby Abbotsford for storage and eventual scrapping—cost to the tax payers of Canada was approximately $300,000.00 not including repairs ($4.5 million today). Photo by Fenwick, DezMazes Collection, via No.5 OTU Facebook Page

At some point during his lonely walk back towards the flight line in the cold and dark, Scratch decided that if he was in a for a penny, he was in for a pound. The wrecking of one of His Majesty's mighty Liberators was not enough for him and he picked out a B-25D Mitchell, RAF serial number HD343 (in the post-event inquiry, the aircraft was often mistakenly identified as AD343 by Provost and Security Service). This was no war-weary and clapped-out aircraft as many OTUs were provided in Great Britain, but had come straight from the factory to Boundary Bay the previous April. In the next five hours, it would be flown like never before, and then it would be destroyed.

After dragging away the wheel chocks, he ducked under the belly of the Mitchell and clambered through the crew hatch ahead of the bomb bay, pulled it shut, squeezed his way into the captain's seat, and strapped in, where five hours later he would die. Using his toe, he unlocked the flying contols, then adjusted his seat for his height. Starting the starboard Wright Twin-Cyclone engine first, he primed the engine by turning the big three-bladed prop through four revolutions before engaging the starter. He did the same with the port engine. Once he had both motors running, he checked his fuel supply and found he had a full fuel load, enough it would prove, for more than five hours of aggressive flying.

If anyone further west at the maintenance hangars had looked east along the ramp, they would have seen little in the dark, perhaps the faint blue flames of Scratch's engines licking the night air, but they would have heard the whine and cough of the engine starts followed by harmonized roar of the two big radials. It's doubtfull that Scratch went through the normal B-25 check lists and litanies, drunk and hurried as he was, but he would have to sit there for a short time as pressures and temperatures rose to their proper levels. Soon, he released the parking brake, pushed the throttles forward, pulled out of the line and moved off eastward for the second time that night.

As he lumbered down the taxiway that led to the thresholds of both Runway 20 and 25, Scratch was being followed by two Provost and Security Service airmen in a panel wagon—Acting Corporal Dilworth and LAC Lockheed. They later testified at the court of inquiry that Scratch was taxiing along with his landing lights clearly on. They knew that there was no scheduled flying that night and that the flare path had been turned off, so they alerted the tower by telephone from one of the hangars. They were told that there was no authorized flying and so got back in their panel wagon and pursued the taxiing aircraft. Scratch made sure not to make the same mistake he made with the Liberator half an hour before and rounded the 180 degree turn without further incident and set up on Runway 25 heading west. The runway lights had been switched off for the night the evening before, but Scatch had the benefit of his landing lights.

Most reports and testimony of Scratch's take-off in the B-25 that night, as well as recent published articles, indicate that he had made his take-off without the aid of lights and only switched his navigation lights on after he had taken off. The station diary for that morning states that it was overcast trending to scattered cloud during the time that Scratch was trying to start the Liberator and then the Mitchell—not the brightest of night skies. How he was then able to start, taxi, position and then execute a full take-off roll in a B-25 in total darkness had created doubt in my mind until I read the affidavit from the two security service airmen. Take-off distances, of course, vary according to winds, temperature, weight and altitude, but I could not understand how Scratch managed to roll down nearly 3/4 to 1 kilometer of darkened runway without lights. I would be uncomfortable driving at 40 kph for more than 100 meters in total darkness, and yet a drunken Scratch would have been rolling in excess of 150 kph in the dark around the time he lifted off. The men following Scratch were only 100 feet behind him when he took off, and they state clearly that his landing lights were on for the entire length of the roll, and were then switched off when the Mitchell was airborne.

Being informed by the Provost officers, the duty person in the tower, Leading Aircraft Woman Joan Barclay, sent another WD [Women's Division] out to the ramp to investigate. Barclay stated she could not hear the Mitchell's engines or see anything at that point. Before the WD could report back, Barclay stated that she saw the landing lights of an aircraft come on “for an instant and then there was a roar and the aircraft took off on Runway 25. When he was about 60 feet off the ground the pilot turned on his navigation lights. He took off at 0454 hours...”. The sun would not rise over the horizon for nearly four hours — at approximately 08453. Given that the two provost men were following close to Scratch, I am inclined to accept their testimony that Scratch did in fact take off with lights.

With his nav lights on Scratch climbed into the black morning sky and what happened over the next five or so hours has become a Royal Canadian Air Force legend of sorts. The story, as it actually happened, is extraordinary on its own, but a number of false and wildly colourful embellishments have distorted the truth over the years and continue to do so to this day. AirForce magazine's Terry Leversedge definitively dispelled many of these myths last year, yet other writers who have told his story since the recent Horizon Air event continue to promulgate this baloney. For instance, there is no record that Scratch flew down to Seattle and buzzed that city—he never even crossed into the United States. Nor is there evidence that he flew down Vancouver's Burrard Street below rooftop level while guests at the Hotel Vancouver looked down at him from their windows. One particualry silly story suggested he deliberately bounced his tires off a rooftop. The truth is still stranger than fiction.

The exact chronology of the lengthy, ill-advised, dangerous and entirely illegal display that followed is confusing, embellished as it is by exaggerations and utter fabrications about what he in fact did that morning. Various sources such as squadron and station diaries and testimonies offer close but differing time estimates for certain events from take off to his final moments. Wherever possible, I have utilized the times found in signed affidavits from the later inquiry testimony.

After taking off in the dark, Scratch began an extraordinary and horribly dangerous exhibition of low-level night flying that simultaneously terrorized the base and amazed knowledgeable witnesses. According to his own signed testimony, at about 0515 hrs, the Station Commander, Group Captain Douglas Bradshaw was woken from his sleep by the sound of the Mitchell's engines at full power. His house was six miles southwest of the airfield at the base of a 150-foot cliff on Tsawwassen Beach on the Strait of Georgia and just a few hundred meters from the border with the United States. Ten minutes later, he heard Scratch in the dark thundering overhead so low that the windows of his home were rattling. Following a call from LAW Barclay in the tower, Bradshaw was dressed and in his car and at the airfield by 0600 hrs. There he recruited a pilot, radio operator and navigator and had them take another Mitchell up to find and keep contact with the rogue Mitchell and its pilot. This Mitchell took off at 0712 hrs and would stay in the air until the arrival of fighter aircraft from RCAF Station Patricia Bay (north of Victoria on Vancouver Island) around 0900 hrs. Barclay had telephoned Western Air Command Headquarters in Abbotsford, about 45 kilometers to the west, to inform them of the situation. Around 0630 hrs, Scratch turned towards Abbotsford and was soon heard beating up that airfield—still in darkness.

After waking up the brass at Abbotsford, Scratch returned to Boundary Bay and continued his harassment of the base. Norman Green, an airman on station at No. 5 Operational Training Unit and a witness to one of Scratch's low level passes and subsequent beat-ups of the field had this colourful description of events around 0700 hrs:

“7:00 hrs. December 6, 1944, while it was still dark, I was in the mess hall when it was shaken, and dishes fell to the floor as a result of an aeroplane flying low overhead. The same pass shook WDs out of their bunks.”

As the sky lightened and people were assembling for the CO's inspection parade, the wrecked Liberator was finally spotted 0800 hrs at the east end of the airfield. Green's dramatic remembrance of the event continued…

“As usual that morning at 8:00 hrs., 1200 airmen and airwomen, all ranks (I among them), formed up on the tarmac in front of the control tower for CO's inspection. Just as the parade was about to be called to attention a B-25 Mitchell bomber came across the field at zero altitude, and pulled up sharply in a steep climb over the heads of the assembled airmen, just clearing the tower. Within seconds, 1,200 men and women were flat on the ground. The Mitchell then made several 25 ft. passes over the field. Group Captain Bradshaw dismissed the parade and ordered everyone to quarters. Over the next two hours we witnessed an almost unbelievable demonstration of flying, much of it with the B-25's wings vertical to the ground, below roof top level, defying gravity. We were continually diving into ditches to avoid being hit by a wingtip coming down a station road. He flew it straight and level, vertically with the wing tip only six feet bove the ground without losing altitude, defying all logic, and the law of physics.”

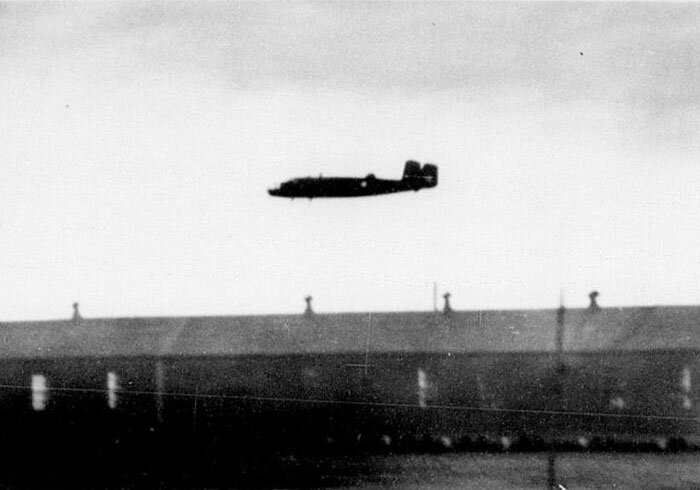

An amazing photo taken on the morning of December 6, 1944 shows Scratch beating up the flight line at RCAF Station Boundary Bay. We can see the blurry silhouettes of a few airmen in the tower, one of whom is likely Group Captain Bradshaw. In the dim light of that early morning, we can see still see the light from the beacon on the roof. Photo: Boundary Bay station photographer Sergeant Herbert Shaw

Another powerful shot of Scratch ripping across the airfield at Boundary Bay. I can't help thinking of Scratch sitting alone in the Mitchell's cockpit—knowing his career is now definitely over, that there is prison time and a court-martial ahead. Having likely sobered up, he has run out of options and knows it. One can't help feel a little sympathy for a man whose decision-making abilities have utterly failed him, if his flying skills have not. Photo: Boundary Bay station photographer Sergeant Herbert Shaw

Scratch continued to beat up the field and fly dangerously throughout the area of the Fraser River delta as the sky lightened. Two Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk fighter aircraft of the readiness section of Western Air Command's 135 Squadron, The Bulldogs, were scrambled at 0835 hrs from RCAF Station Patricia Bay, 60 kilometers west across the Strait of Georgia. Red Section leader Flying Officer James R. McBain and his wingman Pilot Officer E. K. Prentice climbed into a rising sun over Pender Island on a vector for Boundary Bay with orders to shoot down the Mitchell on sight. Arriving over Boundary Bay, they were ordered by Bradshaw to find Scratch but not shoot him down unless he made an attempt to cross the border into the United States. Instead, McBain was to attempt to herd Scratch to Boundary Bay and to convince or force him to land. McBain spotted Scratch at 0900 hrs four miles south of Boundary Bay, very close to the US border at Point Roberts. McBain testified that when spotted, Scratch was flying on a north heading and diving towards the ground. Levelling out at 500 feet, Scratch then crossed the Boundary Bay airfield, turned and came back across the aerodrome at just 50 feet. McBain claimed that from that point on until the last fatal dive, Scratch never climbed above 500 feet.

Dismissing the airmen assembled for muster parade at 0900 hrs for their own safety, the station commander, Group Captain Douglas Bradshaw, a Bomber Command veteran, remained in the control tower to take command of the unpredictable situation. Later he stated… “From then until he crashed at 1010 hours the pilot of Mitchell HD343 beat up the buildings, aerodrome and parked aircraft of Boundary Bay. His flying was utterly incredible as he continually missed buildings and aircraft at times by scant inches. At one time during the last hour he flew the entire length of the tarmac between the lines of parked aircraft and the hangars so low that his propeller tips could only have been inches from the ground. As he passed below me I could see that he was not wearing earphones. His speed practically all the time, I would estimate as varying from 240 to 270 m.p.h.”.

A dramatic if poor photograph of Sergeant Donald Scratch thundering over the rooftops near Boundary Bay followed by Flying Officer James McBain in a Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawk in hot pursuit. Just this month, in an eerily similar episode, F-15 fighter jets were scrambled to deal with Richard Russell in a stolen Horizon Air Q400. Photographer Unknown

At about the time that McBain spotted Scratch for the first time, two more Kittyhawks were scrambled from Pat Bay. The section leader, Flying Officer Albert Suddaby and his wingman Flying Officer F. H. Myles crossed to the mainland to join McBain in dogging Scratch in the Mitchell. From 0900 until 1000 hrs, Scratch continued his extraordinary flying. For some of the time, McBain held echelon position as close as five feet off his left wing and attempted to use hand signals to get him to land, but Scratch failed to acknowledge him. McBain commented that Scratch's flying was “exceptional except that he skidded in his turns”. Skidding in turns is the result of poor footwork on the rudders. Perhaps after nearly five hours of exhausting flying, Scratch's earlier injuries to his ankles were finally getting the best of him.

By this time he was surely sober, having flown agressively and continuously for so long and likely was exhausted as well, for he had not slept for more than 24 hours. After this length of flying time, he was also running out of fuel. The evening before, the Mitchell had been “DI'd” (passed Daily Inpsection and made ready for the next day's flying) and that meant a full fuel load of 810 Imperial gallons. Throughout his exhibition, Scratch had the throttles wide open and working hard. Both McBain and Bradshaw had testified that they believed Scratch had been flying in excess of 270 mph (the maximum speed of a Mitchell) and now he was at the end of his fuel rope.

At shortly after 1000 hrs, about six kilometers north of the airfield and watched by the pilots of the four Kittyhawks, Sergeant Donald Palmer Scratch climbed through 800 feet, and rolled left. McBain, just behind him, watched as his wings went over vertical and his nosed dropped into a near vertical dive from which he would not recover. McBain saw the Mitchell dive straight into farmland on Tilbury Island. Scratch was killed instantly. He was 25 years old.

The shattered remains of North American B-25 Mitchell HD343 in a field on Tilbury Island (an estuarial island around which Fraser River flows) about six kilometers north of the Boundary Bay airfield. Photo: Boundary Bay station photographer Sergeant Herbert Shaw

Luckily, the area where Scratch finally came down was largely farmland in 1944. Today, it is a much more industrialized island. Photo: Boundary Bay station photographer Sergeant Herbert Shaw

Even in his death, Scratch's story was embellished by storytellers who did little actual research and believed every myth they were told. One was that Scratch, just prior to his last dive, turned towards McBain, shook his head, held up his thumb, turned it upside down and then dove to his death. Nowhere in the after crash inquiry testimony does McBain or anyone else state this. Others have said that the crash investigators found the tail's navigation beacon dead centre between the two wrecked engines as if that was some sort of dramatic proof of the verticallity of Scratch's final dive. This fact was not mentioned by crash invesigators and does not appear in offical documents.

A satellite view the area around the Boundary Bay airfield (bottom) and Tilbury Island. Image via google Maps

The destruction of the aircraft was total as was the damage to Scratch himself. A shred of Scratch's shirt was recovered with a laundry mark with his service number on it. This was all they had to identify the pilot of the Mitchell at the scene. Later, among remains, Scratch's left middle finger was found and a positive identification was made possible using fingerprints.

An article from Canadian Press, picked up by newpapers across the country, appeared in the Ottawa Journal the following day. It read:

“R.C.A.F. Student in Mad flight Terrorizes City Before Crash Vancouver, Dec. 6—(CP)— A R.C.A.F. student [sic] pilot ran amok in a twin-engine bomber here today and for four and a half hours endangered the lives of civilians and servicemen as he dived and performed seemingly impossible manoeuvres before plunging to his death.

An attempt was made to drive him down to an airdrome by using fighter planes but pilots were instructed not to fire on him. He paid no attention to their efforts and continued his wild acrobatics. Time after time he put his big craft into dives.

The plane missed persons, buildings and parked aircraft by inches.

Finally, from a height of about 1,000 feet he went into a roll and dived straight into the ground at Tilsbury [sic] Island 6 miles south of Vancouver. The pilot was killed instantly.

Next-of-kin have been notified and the name of the airman will be released shortly.

Western Air Command officials said that the mad flight was entirely unauthorized and that the pilot was alone.

Twisting, rolling, diving without leveling off during the entire flight, the plane went through what flying men termed “impossible manoeuvres”.

Again and again the plane roared over airports near Vancouver, and shot earthward in racing power dives. It streaked across aerodromes below hangar height.

Airmen watched open-mouthed as it shot past parked aircraft, hangars, buildings and persons standing on the ground, missing everything by a hair's breadth.

Two days later, on 9 December, a second CP story appeared in the Ottawa Journal in which Scratch's name and history were detailed more. The article centres around comments made by Air Vice Marshal Francis Vernon Heakes, the Air Officer Commanding (AOC) Western Air Command. Despite Scratch's egregious crimes and failure to live up to the air force code, Heakes could not hide his admiration for his flying skills. Today, I doubt very much that such a high-ranking officer would add such a comment when speaking to the press. The article reads:

“Alberta Airman Who Staged Wild Flight to Death Vancouver, Dec.9—(CP)—Sgt. Donald Palmer Scratch of Ashmont, Alta., who staged a sensational display of aerial acrobatics in a Mitchell bomber at Boundary Bay Wednesday before plunging to his death, Air Force officials announced today.

It was a repeat performance for Sgt. Scratch. He had been discharged from the R.C.A.F. August 31 in Newfoundland after a similar unauthorized flight in a Liberator bomber.

Before his wild sky ride over the Boundary Bay station, 20 miles south of Vancouver, and briefly over Vancouver itself, Sgt. Scratch badly damaged a Liberator at the Boundary Bay field in an attempt to take off. Scratch left the damaged plane and took off in a Mitchell for his 4 1/2 hour ride.

Air Vice-Marshal F. V. Heakes, air officer commanding, Western Air Command, said Scratch was an officer when he staged his wild ride in Newfoundland, presumably because he had not been permitted to fly as a first pilot.

“He was court-martialed, and dismissed from the service”, said Air Vice Marshal Heakes. “He was permitted to re-enlist as a sergeant pilot at that time when there was a scarcity of flying personnel, the air vice marshal added.”

He said that under the present rules it is not possible for an airman to re-enlist after being dismissed from the service.

Air Vice Marshal Heakes said there are not more than five persons who could have given such a display of flying as put on Wednesday by Scratch.

“We have included a psychiatrist on the court of inquiry”, he said.

Air Vice Marshal Heakes said the crash could have been caused by failure of Scratch's gas supply.

“The motor on one side might have failed and the other have pulled him over in a roll and into the ground”, he said

That last statement from Heakes, suggesting that Scratch may have run out of fuel, would, after the investigation, become the preferred cause of Scratch's final crash. The accident investigation concluded that the cause could not definitively be stated. It offers up five possible underlying reasons for the final act of Scratch's flying that morning—the roll left at 800 feet and the fatal vertical dive. Without getting into the exact wording they are:

(a) Pure accident as a result of loss of control at high speed

(b) Failure of the fuel supply to the left and lower engine, leading to the powered upper engine to cause an unintended dive

(c) Loss of control due to physical exhaustion

(d) Suicide (they ruled this out citing evidence from “Witness No 11” — Squadron Leader Badger, the Senior Medical Officer who said he was quite sane.)

(e) Insanity. Also ruled out by the tesimony of Squadron Leader Badger

The consensus was that Option (b), failure of the fuel supply, was the most likely cause of Scratch's last dive. But he would most certainly have known that after so many hours of full throttle flying, he was perilously close to running out of fuel, yet he chose to ignore his fuel state and fly to his death.