WITNESS — Gunfight Over Maisontiers

Image by Dave O’Malley

A dogged amateur historian from France pieces together the events of a terrible night over the small French village of Maisontiers and the downing of Lancaster LM484, proving it’s never too late to know the truth.

A Mother’s Sacrifice

At around 10:30 a.m., on a cold and windy 11 November 1990, a woman in her late eighties by the name of Mrs. Elsie May Pearce walked slowly and sadly up the broad gray granite steps of the National War Memorial in Ottawa. Ahead of her lay a single bright red wreath made from poppies and purple ribbon, laid by the Governor General of Canada just moments before. Beside her walked a man carrying a wreath for her to lay. Behind her, in total silence stood a nation, all eyes on her frail frame.

Under pale pre-winter light, a cold wind drove down the Ottawa River valley, sliced across crowded Confederation Square from the northeast, watering old rheumy eyes, snapping ensigns and battle colours, driving personal thoughts deep inside the thousands standing there. Across Canada, a nation watched on television as Elsie stopped in front of the Memorial, took the wreath handed to her from her attendant and placed it on the step of the Cenotaph, stepped back and stood in silence.

Canada stood in silence with her, for she was the Silver Cross Mother*, an honorific so terrible that no one could desire it. Of all the dignitaries who would lay wreaths that day, from Governor General Raymond Hnatyshyn to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, no one stood for so much as did Elsie, for she represented the real and hard price of war. She stood for heartbreak, futility, honour, duty, unimaginable sacrifice and the debt we owe. The Silver Cross Mother is selected to represent mothers who have lost sons or daughters in military action in any of Canada’s wars and battles. Elsie had, for forty-five years, suffered the loss of both of her beautiful young sons.

Standing there, with flags snapping, halyards ringing, and the occasional coughing behind her, Elsie stood stiffly in grief for a moment as she no doubt thought about and spoke in her heart to her sons, Stewart and Jack. Stewart, the oldest, was a Spitfire pilot with 412 Squadron Royal Canadian Air Force and was killed in action during an armed “recce” in December of 1942. His squadron was attacked by FW-190s over the English Channel and he failed to return. Young Jack, an Air Gunner with the Royal Canadian Air Force was killed 20 months later on the night of 26–27 July 1944 when his Lancaster was involved in a gunfight with a Luftwaffe night fighter over the small French village of Maisontiers. It was one week before his 23rd birthday.

No doubt, her head swirled with images of their handsome and smiling faces, the cut of their uniforms when she last saw them, the things they did as boys and, if her memory was good, their voices. As all of Canada looked at her back, she was forced to once more suffer her unthinkable loss, this time in front of an entire nation. It was both an honour and a terrible trial. Her strength, her sorrow and above all, her dignity... these a nation would embrace as their own on this day of remembrance.

Watching her that day was her grandson, a middle aged man by the name of Jack Trumley. Trumley was the son of Elsie’s surviving daughter Ruth and Ken Trumley, a career military aviator and former Spitfire pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 442 Squadron. He was the nephew that Jack and Stewart would never live to meet. He watched as his grandmother stood in front of the nation and bore the weight of grief for all of them.

Let’s move ahead now to the winter of 2013–14. Jack Trumley, searching for information on the lives and deaths of the two uncles and heroes he never met, comes across a post on the internet which described, in powerful detail, the last minutes and aftermath of Uncle Jack’s last moments on earth. But I am getting ahead of myself.

A mother’s terrible sacrifice upon the altar of freedom. Mrs. Elsie May Pearce, of Toronto, Ontario, lost both of her sons in the Second World War—Stewart (left) and Jack (right). The oldest, Flight Sergeant Stewart William Pearce was a Spitfire pilot of 412 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. He was killed on 12 December 1942. He was 22 years old. Flight Sergeant Jack Gordon Pearce, RCAF, an air gunner with 619 Squadron RAF, was killed two years later on the night of 26–27 July 1944 over the village of Maisontiers, France. Such was the sacrifice that Elsie May Pearce made to the war effort, that she was chosen as the 1990 Silver Cross Mother* for the Remembrance Day Ceremonies at the National War Memorial in Ottawa. Sister Ruth (centre) would become Ruth Trumley. Her son, named for brother Jack, would bring this story to our attention 70 years later. Photo via Jack Trumley

A Rain of Sorrow

A Rain of SorrowThe sky overhead Europe in the Second World War was a battlefield like no other before or since. Day and night, swarms of multi-engine bombers drove deep into enemy territory on both sides of the conflict. Day and night hundreds, even thousands of fighter aircraft rose into the sky to destroy them.

On any day from the glowering, doom-filled autumn of 1939 to the hopeful spring of 1945, flying war machines seamed the skies of the continent from the Irish Sea to the Russian Steppe. Intruders swept across the Low Countries, bomber streams were mauled in the high altitude gauntlet, fighters danced the dance of death, and lone coastal aircraft patrolled far out to sea. It was at the same time indiscriminate and focussed, impersonal and personal, mechanical and biological. The only thing that relieved the stress of the endless aerial battle was unsuitable weather.

Every night, every day, aircraft fell victim to each other and to attack from anti-aircraft fire. Fighters destroyed other fighters. Submarine hunters disappeared into the void. Impersonal flak bursts sieved giant thin-skinned bombers. Swarms of fighters hounded, clawed and brought down scores of heavy strategic bombers on every raid. Engines malfunctioned. Aircraft caught fire. Bombers collided in the dark. Pilots made mistakes. Systems failed. Crews passed out from hypoxia. The result was that the uncontrolled broken hulks, the spinning and flaming remnants, and the still flying airframes of thousands upon thousands of bombers, fighters and transports rained down over the European countryside—on a daily basis. It was a rain of metal, a rain of fire, a rain of youth, a rain of sorrow.

All across Europe, dawn would reveal yet another terrible harvest of broken metal and human flesh, as quiet rural communities would become the unwanted place where young men paid the ultimate price. This photo is typical of the tragic rain which fell upon Holland during the war—Lancaster ME858 of 514 Squadron RAF. None of its crew, returning from a raid on Homburg, was able to exit the doomed Lancaster and all seven were killed in the crash. This crash happened just one week before the loss of Jack Gordon’s Lancaster in France. Photo via Dutch historian Tom Bosmans and Regina’s Balfour Collegiate website (http://balfour.rbe.sk.ca)

Related Stories

Click on image

In the end, wars become numbers. Numbers of aircraft built, mustered, damaged and lost. Numbers of airmen killed in action. Numbers of sorties and total tonnage of ordnance delivered. Numbers of enemy aircraft destroyed balanced against the numbers of Allied losses. Thousand plane raids. 425 Squadron. 619 Squadron. 6 Group. The Mighty Eighth. Thirty sorties to complete a tour. Seven members in a Lancaster crew. B-17, P-51, C-47. Numbers, numbers, numbers.

In one night’s raids against targets in Germany, Bomber Command might typically lose 20 Lancaster and Halifax aircraft—four-engined bombers coming apart after flak bursts detonate their payloads, exploding into flames after being stalked and raked by cannon fire from German night fighters, or simply colliding with each other in the crowded and cold, black skies.

Twenty aircraft. One hundred and forty men. One hundred and forty mothers waking in the night, gasping for air with a terrible premonition. One hundred and forty families soon to be notified of the loss of a son, a brother, a husband, a sweetheart. One hundred and forty telegrams. One hundred and forty circles of human friendship broken. Some of these men would jump and survive, but most would die. A hundred or more new tombstones to carve after the war. A hundred or more death notices in the local papers. One hundred and forty holes in the roster to fill with new recruits. Just one night. Just one battle. Night after night.

And yet, this was only part of the toll, a fraction of the waste, a drop in the bucket. By day, the Americans suffered equally. For the Russians, Germans and Italians, it was the same... even worse. And then there was the Pacific War.

Into the Night

For most of these families, the exact circumstances of the deaths of their beloved sons would never be known. Most would have to settle for two telegrams from their governments. The first would have those terrible words “Regret to inform you... missing in action...” Months later, the little window left open by the word “missing” would be slammed shut forever: “Regret to inform you... believed killed...” The lucky ones would get a letter from the squadron commander with a few pieces of the puzzle to ponder—the day, the time, the place. For the really lucky ones, a squadron mate, returning after the war, would pay them a visit and regale them with loving stories of their son’s time on squadron—the camaraderie, the good times, the duty done, the honour bestowed, the professionalism and perhaps the last night of his life. Years after the death of Spitfire pilot Flying Officer Stewart Pearce, Elsie Pearce was visited by his wingman. He was guilt-ridden about what had transpired when the squadron was attacked. He had lost contact with Pearce in the dogfight and had returned to base without him, only to learn that he had not made it. Having lost contact with him in the flight he could offer no details of his demise.

Many families would request, even beg, the bureaucracy for the possession of their beloved’s logbook—that regimented yet very personal record of their movements, training, combat and even thoughts. These logbooks were written in the very hand of their sons—the flourishes, ascenders and descenders that their mothers knew so well. The logbook was a record of their life from the moment they left their families and began the training that would lead them to their deaths. These logs were of great comfort to the families who obtained them, but the recording stopped the day they were killed and shed no light upon their last moments. Almost two years after the war, the RCAF finally released the logbooks of Elsie Pearce’s two sons and sent them to her.

By war’s end, Elsie May Pearce had only memories of her two beautiful sons. She requested from the RCAF the logbooks belonging to each of them and was finally granted possession a year and a half after war’s end. Each logbook, written in the familiar hand of each of her sons, told her of their movements and actions and even thoughts as they fought the war far from their home. There is no doubt they brought some solace to her agony, sad as they were to read and hold in her hands. Image via Jack Trumley

The vast majority of families would never have that word we now know so well—closure. They would go forward through their lives never knowing how their son had died, always wondering—Did their sweet boy die quickly? Was his body found? Was he treated with respect and honour? Were there witnesses? Was there someone who cared to cover him up? Did someone hold him as his heart beat its last?

Today, all that is left of the ones who were found are limestone tombstones in war graveyards scattered across Europe, from Scotland to Germany, from Denmark to Tunisia. For the others, the thousands lost over seas or who simply vanished into the night, only their names live on—in books of remembrance, on memorials from Malta to Runnymede, and on bronze plaques in churches and schools everywhere. Stewart Pearce’s body was never found. Only his name remains, carved into the wall of the Runnymede Memorial. The body of his younger brother Jack lies in the graveyard at Pornic, France.

The grave marker for Flight Sergeant Jack Pearce in the war cemetery at Pornic, France. For years, he has lain here, waiting for his story to be told. Image via Jack Trumley

Back to the Light

Now, over the past few decades, the magic of the internet has created a new and powerful way to provide answers to questions that have echoed unheeded in the empty hearts of family members since the loss of their young men seventy years ago.

The World Wide Web has given rise to a powerful new breed of amateur historians in Europe whose passion is to find the back stories behind the thousands of aircraft that came to ground in their towns, regions or countries. They are changing the way history is told. Today, passionate and dedicated historical researchers, military enthusiasts and aviation archeologists like Holland’s Jaap Vermeer and France’s Maurice LeBrun can connect online military records with eyewitness accounts through history and aviation archeology forums and social media sites like Facebook to build accounts of events now more than 70 years old. They have learned to scour the internet for references to singular events, to conduct forensic research and to compile details that the military had neither time nor ability to collect during the war. They now can tell the stories of events that transpired in their communities that were once deemed lost behind the miasma of time and memory.

Men like LeBrun do a better job of remembering our fallen Canadian aviators than any Canadian or French government agency could ever do—with more emotion, kindness, dignity and gratitude than most Canadians could ever muster. While they shed light on our nation’s inability to connect with our past and our largely unmet duty to honour our heroes, they do more than keep alive their memory... they bring it to life.

One of LeBrun’s projects was to find everything he could about the crew and the last moments of Lancaster LM484, the aircraft in which Jack Pearce met his death.

Gunfight over Mainsontiers

Flight Sergeant Jack Pearce and the entire crew of H for Harry (RAF Serial No. LM484, coded PG-H), a 619 Squadron Lancaster, were killed in action over a small rural village named Maisontiers in Western France. They, and their squadron, were part of a large bomber stream en route to strike the rail assembly yards outside the city of Givors, France, some 250 miles to the southeast. They got as far as Maisontiers, when they were set upon by Luftwaffe night fighters. In a running gun battle, the crew of Lancaster LM484 went toe to toe with a Junkers Ju88 night fighter over the small village and its encircling farms.

Maurice LeBrun, while researching the story of the crash of Lancaster LM484 at Maisontiers and looking to piece together the events of the night of the 26/27 July, 1944, interviewed an eyewitness to the battle and the aftermath of the crash. The eyewitness was a teenaged farm boy in 1944 by the name of Gabriel (Gaby) Cailleau. His account went far beyond any information available to the Royal Air Force at the time or even after the war. After interviewing Gaby, now more than 80 years old, he sent a letter to a Mrs. Murfitt, the sister of Len Rothwell, the Royal Australian Air Force radio operator aboard Lancaster LM484. He had previously been in touch with her and had just received from her a photograph of Rothwell. The letter, written in French and translated by a friend into English, is a gripping account of the last moments of LM484 and a tragic story of the aftermath, and in particular, Cailleau’s powerful memory of finding the body of Flight Sergeant Rothwell in a rain sodden field.

A hard luck Lanc—Lancaster (PG-H) of 619 Squadron RAF in flight over England. On the night of 26–27 July 1944, Flight Sergeant Jack Pearce of the Royal Canadian Air Force was the tail gunner with the crew of a similarly marked Lancaster (PG-H), bound for a low-level raid on the rail assembly yards of Givors, France. The Lanc in this image, RAF serial number LM446, would fail to return from an attack on the Gnome–Rhone aero-engine factory at Gennevilliers, France, on 9–10 May 1944. It would be replaced by Lancaster LM484, the aircraft in which Pearce and his crew were killed two months later. Fourteen airmen lost their lives in the two losses of PG-H. Photo: Royal Air Force

The crew of 619 Squadron’s PG-H (LM484) was comprised of (clockwise from upper left) Flying Officer Ronald George Turvey (Pilot, Royal Australian Air Force, aged 20), Flight Sergeant Len Rothwell (Radio Operator, Royal Australian Air Force, aged 20), Sergeant Joseph Harry Gilliver (Bomb Aimer, Royal Air Force Volunteer reserve, aged 31), Warrant Officer Second Class Thomas Francis Galbraith (Navigator, Royal Canadian Air Force, aged 29), Flight Sergeant Jack Gordon Pearce (Tail Gunner, Royal Canadian Air Force, aged 22). Not pictured here: Sergeant Edward Graham (Flight Engineer, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, aged 36), Sergeant Reginald James Thair (Mid-upper gunner, Royal Air Force Volunteer reserve, age unknown). Photos via Maurice LeBrun

LeBrun’s letter, written with heartfelt regard for her feelings, also shed light on the last minutes of the Lancaster’s tail gunner, Flight Sergeant Jack Gordon Pearce, Elsie Pearce’s only living son. The attacking night fighter was also shot down by the gunners of LM484 and there is no doubt that Pearce had much to do with that, night fighters would attack from behind and below in an attempt to avoid the defensive fire of the Lanc’s gunners.

The letter was posted on the web and came to the attention of Canadian Jack Trumley, who was searching for details of the death of his uncle Jack. Trumley shared it with David Lloyd and Maureen “Spitfire Mo” Patz of the Spitfire Society, who in turn shared it with me. The power of the internet and the passion of amateur historians allow us now to tell the story of what happened to Jack Pearce, Len Rothwell and the crew of Lancaster LM484.

Here, now, is the letter written by LeBrun to the sister of Flight Sergeant Len Rothwell:

Dear Mrs. Murfitt,

Sorry for the tardiness of this letter, but I do not speak English and so have had to use a translator. Please excuse the poor translation.

It is with a great respect that I write you this letter, it’s a bit long but I think that after 64 years, you should know what happened on the 26th and 27th of July 1944. I suggest you make yourself comfortable.

My name is Maurice LeBrun. I am married to a French Canadian (from Québec), and have three children. I am retired from the [French] army after 15 years with the paratroopers. Because I am only 51, I still work—I am a school bus driver. The tardiness of this letter is also due to having to organize all of the information I’ve gathered. I have been researching the missions of the crew of the LM484 [Lancaster of 619 Squadron RAF] for the past 1 year and 2 months.

Thank you for sending me a photo of Len. I had the photo enlarged and showed it to Gabriel Cailleau, the person who found Len on the 27th July 1944. To lengthen the suspense, I wrapped the photo of Len. Gabriel had only seen him once, but after 64 years, he still remembered him.

The photo was unwrapped and he had a good look at it. Gabriel never believed he would see him a second time. He was instantly transported back 64 years (Gabriel had just turned 80 in January 2008) and was very emotional as he recounted how he had discovered the body of your brother in a field behind his home.

To understand the story, you have to imagine the landscape in 1944. Gabriel was 16 years old and lived in the country 5 km from the village of Maisontiers. He was the son of a farmer and had a brother who was 1 year older than him. He worked hard. His father had been deported to a concentration camp (one from which no one returns) to help salvage the weapons from paratroopers. Ten months had passed since his father’s arrest by the German police. He had to organize the farm. His mother also worked very hard on the farm—mainly the domestic duties. His brother was in charge of milking the cows and the animal feed, etc. Gabriel (nicknamed Gaby) took care of the small animal pens (chickens, rabbits, ducks, etc.) and the crops.

Gaby and his brother slept in the attic in a small room arranged for them both. When Gaby couldn’t sleep, he listened to the strange noises at night, the calls of nocturnal birds and other animals he recognized (he had a good ear.) In 1944, heavy bombers flew overhead most often, several times per week, but the airplanes were quite high and he could usually not see them at night.

But on the night of the 26th to the 27th July 1944, while summer storms rumbled and lightning lit up the fields, from his window he could see a big, round, yellow moon with clouds passing in front of it (the clouds resembled a freight train.) Just as his brother told him to go to sleep because there would be a lot of work tomorrow, a dull noise/thud grabbed his attention. He saw a squadron of bombers flying in front of the moon. They were not very high, only about 900 metres. The clouds then obscured the moon and he tried to go to sleep, only to be awoken by other noises—almost like little firecrackers exploding. His brother woke up too. At 23:30, a bomber already engulfed in flames passed within view, followed by a German plane. Both were involved in an aerial battle. The bomber passed by again, still followed by his enemy who was still firing. Several minutes later Gaby heard a huge explosion. He wanted to go outside to look, but his brother stopped him—they could still hear gunfire and it was raining quite hard.

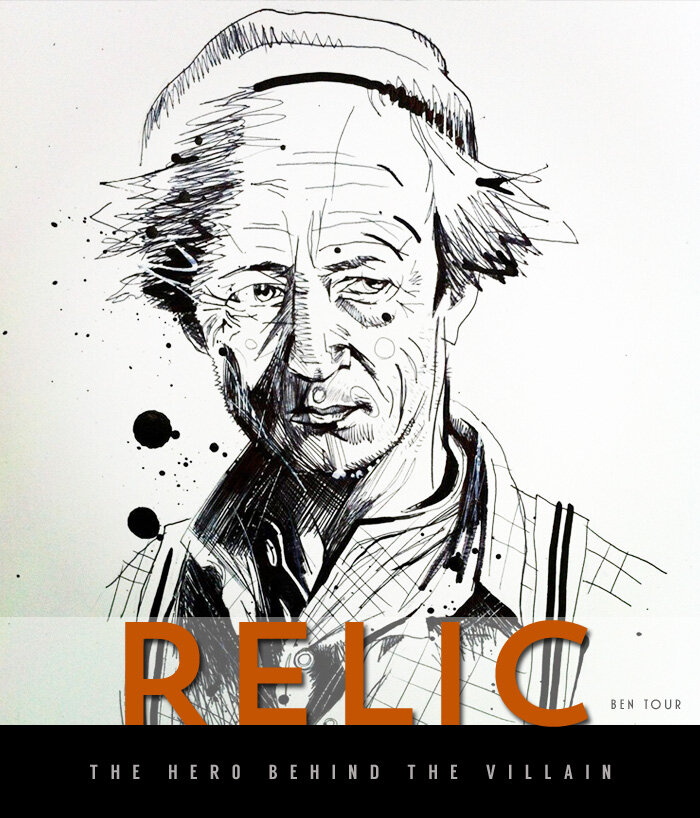

Eyewitness Gabriel Cailleau, a 16-year-old boy at the time of the aerial battle, woke to the sound of 619 Squadron Lancasters flying low over Maisontiers and outlined by the moon. The images of that night would be burned into his memory for his whole life. Photoshop image by Dave O’Malley

Gaby went back to bed, with the sound of gunfire and the rain beating against the window, and hoped the night wouldn’t be too long. At dawn it was calm. He got out of bed and dressed quickly—not an easy feat with a broken arm. He broke his arm coming back from a Bastille Day (14 July) dance in the village of Maisontiers. He had fallen off his bicycle and broken his arm. He ran down the stairs, his brother following closely behind, and opened the front door. The rain had stopped and he saw smoke coming from the woods in the distance. It was 06:15 a.m. The boys ran towards the smoke as fast as they could, each trying to be the first one there.

As they got closer, Gaby’s brother slowed him down and they continued marching in between the airplane debris. The 30-ton bomber had been reduced to tiny pieces, some of which were still burning despite the heavy rain the night before. The fields they were walking through belonged to their family, but had been rented to a Spanish ex-patriot they called Mr. Olive who had set them up as a small farm. Mr. Olive was an agricultural labourer who worked for them. The farm Mr. Olive had was called the Taconnière and was named after a river; the farm where they lived was called La Pommeraie.

Arriving at the woods, the Bois de la Chagnasse, they discovered the mutilated and amputated bodies of the crew (I am really sorry to have to describe this in detail, but I think it is necessary to relay the story.) The bodies were spread out over the paddocks and were covered with an oily, black substance (I’ll stop with the details soon.) People from neighbouring properties arrived with Mr. Olive, the tenant of the Taconnière. Mr. Olive told Gaby’s brother to stop his mother from coming over and told Gaby to go home as well. Gaby’s brother took off running and he took his bicycle.

Around 07:30 a.m., the milk collector arrived at the farm with his noisy truck, as per usual, to pick up the jugs of milk. Gaby helped him carry the jugs. The milk collector told him there was a white object in the field—he thought that maybe a sheep had died in the middle of the night. Gaby knew there were no sheep in that paddock, so he let the jug he was carrying drop and ran in that direction. He saw in the distance the white object, but what was it? The closer he got, he realized it was a parachute… and at the end, a man on his back.

Arriving at the man, tired from running, he looked at him for a long time. He was not moving, his eyes were open. Gaby understood that he was dead. The body was soaking wet and Gaby could see a wound underneath the chin. He was still wearing his leather helmet. Questions flooded into Gaby’s head—Who was he? What was his name? Was he English? And then Gaby started looking through his pockets.

He found a compass, a razor, French currency and a laminated French map. Gaby noticed that he was wearing a sky-blue uniform with flat shoes and that his feet were joined to his hands along the body. He looked back up towards the parachute. It was half burnt, which would explain the quick descent. He looked again through his pockets and found the letters RAF. He put everything back in the shirt of the aviator. He put the parachute over the body, so that the canvas would not blow away. He then put several lumps of earth on top of the parachute because the wind had just picked up. It was Wednesday, 27 July 1944.

You probably would have guessed that Gaby had just discovered Len’s body. Dear Madam, I am distressed to have told you all of this, but I believe that you need to know how your brother met his end.

After this, Gaby went back the way he came and already saw other people coming in from nearby villages. He found the mayor—Mr. le Baron de Wissocq—and told him that he’d found another aviator. The curious villagers had started to gather the pieces of the airplane and all sorts of things—it was wartime after all and everything was scarce. Everything they gathered would be sold on the black market. The French gendarmes arrived on the property and dispersed the curious and the thieves.

Gaby brought the mayor towards the body of the aviator fallen in the field. In the short time that it took to fetch the mayor, as they approached, a man was already stealing things from Len, including the French money and a ring that Len had on his finger. Looking up, they saw the man running away. So the mayor called the gendarmes, who took their car and caught the thief. The thief gave back Len’s effects—except the ring as he hadn’t taken it. The thief was brought to the police station then transferred to the prison in Bressuire.

Maisontiers is a very small village between the towns of Bressuire and Parthenay in the west of France, situated in the region of Poitou-Charentes. On the night of 26–27 July 1944, part of an RAF bomber stream, en route to the city of Givors, some 250 miles to the southeast, passed over the village along with attacking Junkers Ju88 night fighters. This map gives approximate positions of the towns mentioned in this eyewitness account. Map: Dave O’Malley

The mayor (le Baron de Wissocq) wrote and spoke English and therefore had no trouble identifying Len Rothwell of the 619thSquadron. It was now 11:30 a.m. and a large vehicle from the German army with 4 officers on board arrived in the Deux-Sèvres. The Major Reis, chief of the German army in the Deux-Sèvres, arrived escorted by several sidecars, followed by a military truck and armed men. Once they had disembarked, the orders rang out and the soldiers threatened the remaining civilians (including Gaby) with their weapons. The Major was speaking to the Mayor when an ambulance arrived. The German nurses gathered the bodies and went in search of Len. Once this was complete, the ambulance and the officers left but some guards remained near the debris from the airplane.

The bodies were identified by the coroner and the German police upon arrival in Parthenay. While the bodies were being identified, trucks gathered the pieces of the airplane—the wings, the wheels, the engines, etc. Later the pieces were melted down in the foundry at Niort and used to make German planes (a Lancaster bomber was made from around 85% aluminium.)

On the Saturday morning, the Germans returned to the village of Maisontiers—an officer in a sidecar lead the group and asked for the Mayor. He was followed by a military truck. The soldiers lowered 6 coffins from the truck, made from blonde wood (Poplar) by the carpenter in Parthenay. Already, the curious villagers started arriving at the church, but the officer ordered the crowd to disperse. Only the mayor and the parish priest were allowed to assist with the burial. No honour and no service would be allowed. Six coffins and not seven—some of the mutilated body parts had been put into one coffin. Once the burial was finished, the Germans left with an expression of hate on their faces (these comments were made by the parish priest in a note couriered to the Monseigneur de Poitiers.)

The next day, the mayor and the parish priest decided to celebrate mass and give some honour to these poor souls. Villagers from Maisontiers and surrounding villages came with gifts of flowers and wooden crosses were installed on the graves.

There you are, dear madam, the events of the 26th July 1944 and the days that followed, as told by Mr. Cailleau (Gaby). To finish, I would like to explain to you what happened during the aerial battle.

The English bombers were flying over their sector of French airspace (France had been occupied by the Germans since June 1940) and the Germans were planning their counterattack. “DCA’s” (Defensive Counter Air fighters) and “night hunters” were deployed over French territory. In 1943, the Americans joined the English in battle. The Americans bombed during the day from very high altitude and often missed their targets while the English bombed at night from lower altitude.

The mission destroyed the centre of “railway sorting” of Givors—an important hub for railroad traffic. Trains of panzers (German tanks) were signalled. Flying over the sea (English Channel) and then into French airspace, the bombers first had to evade the DCA of the enemy, then the “night hunters” [Nachtjager] Ju88s took over. The Ju88 had very advanced radar for that time. These planes were scattered and concealed over very rugged and wild terrain. One field could have served as a base and perhaps a wooden shack or several iron sheets could have concealed them and then by radio, they would take off by night. To finish describing this airplane, it was equipped with a 20mm gun and several machine guns. The crew consisted of a pilot, a radio navigator and a tail gunner (machine gun). The speed and agility of the German airplanes had no problem attacking the heavy Lancaster bombers.

The night fighter which brought down Lancaster LM484 was a radar equipped Junkers Ju 88. By all accounts, the two gunners of the Lanc, Canadian Jack Pearce and Englishman James Thair gave as good as they got, for it caught fire and crashed as well. The Luftwaffe pilot, Leutnant Otto Huchler was killed in the crash, but his radar operator, Unterfeldwebel Brukner, and gunner, Unterfeldwebel Gebert, managed to parachute to safety.

The Junkers Ju 88 ended the Second World War as the most important German night fighter, despite being developed as a bomber. Early in the development of the Ju 88 it became clear that it would be just as fast as the Bf 110 heavy fighter, and Junkers worked on producing a fighter version of their fast bomber. By the end of 1943, new radar equipment had been developed that was unaffected by British jamming with “window”. This allowed the night fighters to adopt a new system—Zahme Sau (Tame Boar). This was designed to set up long running battles by directing night fighters against the bomber stream as soon as it crossed into German territory. Carrying FuG 200 Lichtenstein SN-2 radar (above), the Flensburg system, which could detect the RAF’s Monica tail warning radar and Naxos, which detected the H2S ground radar used by RAF pathfinders, and armed with upward firing Scräge Musik guns that allowed the fighter to destroy the British bombers from below, the Luftwaffe began to inflict unsustainably high losses on RAF Bomber Command. During the Battle of Berlin of early 1944, losses rose to around 10% per mission. Text via historyofwar.org. Photo: via falkeeins.blogspot.ca

In July 1944, German aviation was on several fronts, especially in Russia. The Ju 88s were limited in number. In order to not miss their targets, the Ju 88 had battle tactics and attacked the bombers from underneath, where they had no protection. An attack from underneath would damage their engines and then the Ju 88 would gain altitude and attack like an eagle and dive at the last in line. This would disable the machine guns at the back of the bomber. Finally, they would use their 20mm gun to attack the poor Lancaster and set fire to it.

Captain Turvey saw that the Ju 88 would not relent so he decided to drop bombs in the fields to avoid the villages. He gave orders to Sergeant Gilliver (the bomber) to drop the fragmentation bombs (this might have been the fatal error.) I remind you that it was raining quite hard, which didn’t help matters and that there would have been quite a panic on board with the engines on fire, people injured, the noise of the storm and the enemy gunfire as well as the bomber losing altitude. The bomber first circled the village of Maisontiers while dropping 3 bombs, the impacts of which are still visible today—the craters are now filled with water. On the second circle of the village, Len, realizing that the airplane in flames was lost and that the enemy was still firing, opened the door and managed to jump towards the village of Billy (the radio operator and the navigator were the only ones to keep a parachute on them because they had more space than the others. So the door fell near the village of Billy, Len jumped, but the flames from the engine burnt his parachute. The plane was diving at 45°, the navigator Sergeant Thomas Galbraith (a Canadian) did not have time to jump. Knowing they were going to die, Gilliver dropped another three bombs too close to the ground, one of which did not explode, but did not have time to drop the cookies (2-ton incendiary bombs). A shell from the Ju 88 must have hit the cookies and the Lancaster exploded before hitting the ground. This explains the pattern of airplane debris scattered in every direction.

A close-up of the area to the northeast of the village of Maisontiers showing the bomb craters filled with ground water that bear witness to what transpired overhead 70 years ago next week. The bombs were released at low level by bomb aimer Flight Sergeant Joseph Harry Gilliver as the aircraft was on fire going to crash land. Image: Google Maps

In late August 2011, a farmer found one of Gilliver’s bombs still intact under the surface of a field he was cultivating. Previously, the field had not been plowed since the bombs fell in 1944. It was removed by explosive experts and detonated near the town of Viennay, a few kilometres to the south. Here we see explosives with the bomb at Viennay prior to detonation. Photo: lanouvellerepublique.fr

he bodies were found the next morning scattered throughout the fields of the Taconnière farm on the edge of the Bois de la Chagnasse. The German plane, which had also been hit, had crashed into an oak tree in the fields of la Fougerit near the village of Amailloux. The radio operator and the machine gunner at the tail managed to parachute successfully and landed at the exit of the village of Maisontiers, then walked to the neighbouring village, Ripère. One had been hit by a bullet in the elbow and the other in the foot. They asked the residents of Ripère for help. Fearing for their families and reprisals from the Germans (4 people had already been deported from the village), the villagers from Ripère gave them first aid, it was probably around 01:00 or 02:00 a.m. At 09:00 a.m., a German ambulance with guards took them to the hospital at Parthenay. The pilot of the Ju 88 had been gravely wounded and crashed with his plane—his body was strewn throughout the field along with the pieces of the plane.

There you go Mrs. Murfitt, the story, after a year has passed since I inquired with you to relate these facts. With the approval of the owner of the woods, I undertook searches and digs and found debris from the Lancaster LM484 as well as debris from the German airplane, but have found nothing of the survivors of the Ju 88—that is more complicated.

My goal today, after 64 years, is to have a commemorative plaque with a photo of the crew of the LM484 for its 20th and final mission, and that the names and faces of these heroes are glorified (until now, only a wooden sign has been erected since the 50thanniversary of the disappearance of the aviators.)

The crew was buried in the tiny cemetery at Maisontiers on 30 July 1944. In 1947, the bodies were exhumed and repatriated to the war cemetery at Pornic. They lie next to one another. Every year, the French and English armies present honours to these heroes. I have included several documents.

Dear Mrs. Murfitt, please excuse me if I have shocked you with this sad story of the 26th July 1944. A book about this battle will be edited shortly. I have been in contact with Jaky Emery, but sadly he didn’t have much in the way of new information to share. If you have any contact with the families of the others who were missing, please let me know so that I can contact them. If you would let me, in my next communication, I would like to ask you questions about your brother Len.

I am at your service if you would like further information.

Please accept my kindest regards and respect, Maurice LeBrun.

This deeply moving letter and gripping account of the fate of the crew of Lancaster LM484 confirms some very important notions. Firstly, it demonstrates that the doomed aircraft and their crews made a profound impact upon the places where they crashed, far beyond a smoking hole in the landscape. In Holland, Norway, France and any other country pinned under the iron hand of the brutal Nazis, these lost airmen and their last moments had a deeply emotional and lasting impact upon the populace, especially the young ones like Gaby Cailleau.

Secondly, it puts to rest the troubling thought that these airmen died some unwitnessed, obscene and ignoble death, ground up by the machinery of war and dumped upon the earth, no more important than the debris of their aircraft. Through Gaby Cailleau’s eyes and heart and through Maurice LeBrun’s determined hunt for the truth, we know with certainty that the deaths of men like Len Rothwell and Jack Gordon were remembered. That their bodies were treated with great respect and sorrow. That their last night would become part of the ancient history of the lands where they lay.

These are the things that Elsie would have wanted to know.

Dave O’Malley

The chard yard of Église Notre-Dame at Maisontiers, close to where the bombs from LM484 were jettisoned. There is a large plaque dedicated to the seven crew members, seen just to the right of the church’s front door. Although the church in Maisontiers was built in the 19th century, the original church on this spot was built in the 1400s, but was burned in the 1700s during the French Revolution. Photo: Stephane Mace de Lepinay

In 2009, Gabriel “Gaby” Cailleau (right) stands with the young grandnephew of Len Rothwell, Lancaster LM484’s radio operator. They stand next to the plaque commemorating the end of the Battle of France, and the memory of the aviators who died with Rothwell. Photo via Maurice LeBrun

In the forecourt of Notre-Dame de Maisontiers stands a plaque which commemorates the 50th anniversary of the end of the Battle of France and, particularly, the resistance fight of the Commune de Maisontiers on the region of Deux-Sèvres and the deaths of the seven crew members of H for Harry on the night of 26–27 July 1944. Photo Marc Bonas / Aérostèles

Remembering Elsie Pearce’s oldest boy, Stewart William Pearce

Flight Sergeant Stewart William Pearce of Toronto, Canada poses casually in front of Big Ben (Elizabeth Tower) at Great Britain’s Parliament in the summer of 1941. Photo via Jack Trumley

This photo of Stewart Pearce reveals the youthful exuberance, personal pride and the fact that he now wears the single stripe of a Pilot Officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force. The Canadian Virtual War Memorial shows that Pearce was a Flying Officer at the time of his death in December of 1942. Photo via Jack Trumley

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Maurice LeBrun, Marc Bonas and Pierre Pécastaingts of France for their passion, their commitment and continuing work to remember the lives of French Resistance fighters as well as Allied airmen who were killed overhead their villages and farms. We cannot thank enough the people of Europe, like Gaby Cailleau, whose memories are still strong after all these years.

In addition, I thank Jack Trumley, the nephew of Jack and Stewart Pearce, who first provided Vintage Wings of Canada with a copy of the letter written by Maurice LeBrun to Australian Mrs. Murfitt and who provided images and support. I would also like to thank French national Pierre Lapprand, a Vintage Wings volunteer who tirelessly and enthusiastically translated the communications between myself and Maurice LeBrun.

Thanks as well to all those who helped link Vintage Wings with the story of LM484: David Lloyd and Maureen Patz of the Spitfire Society.

*The National Silver Cross Mother is chosen annually by the Royal Canadian Legion to represent the mothers of Canada at the National Remembrance Day Ceremony in Ottawa on 11 November. As the Silver Cross Mother, she will lay a wreath at the base of the National War Memorial on behalf of all mothers who lost children in the military service of their nation.

The Memorial Cross, the gift of Canada, was issued as a memento of personal loss and sacrifice on the part of widows and mothers of Canadian sailors, aviators and soldiers who died for their country during the war.